Theme 2: Global Patterns, Systemic Shifts

The concrete changes we are experiencing are shaped by global patterns that have been underway for many decades. These patterns are ‘trends’, and understanding and anticipating future trends has become all the rage in the corporate world for obvious reasons. From the business sector to civil society, analysts try to map different scenarios into the future and navigate uncertainty. However, our political orientation in this Guide differs from some of the more expert-driven, technical methods of analysing trends. We rely instead on our own reading of history and theory, our analysis, observations, experience, stories, and reflections, as well as the facts and information we gather. To understand the present moment, we examine the past, tracking earlier crises, power dynamics, and related struggles for social justice. From there, we map where these trends may lead. Terms included below – What we’re up against – help us name these trends and see how they are interconnected and historically rooted.

Activity 2: Trends analysis

Activity 2: Trends analysis

What does ‘trend’ mean to us? Which trends stand out?

Materials: Flipchart paper, markers, handout: What we’re up against

Plenary: What do we mean by a ‘trend’? Invite responses and discussion. Explain that trends are not only the events and changes we experience in our daily lives and work but also larger patterns – social, economic, political, technological, cultural – that reveal a correlation of forces at play. When the specific and the general are somehow connected, this is a trend.

Identifying global trends may seem abstract, but it helps connect our local and specific situation to a broader range of forces. To begin, ask what new realities or recent incidents may indicate larger shifts and trends. For example:

- The denial and violent rejection of election outcomes, such as the January 6th assault on the US Capitol in Washington, DC in 2020 or the violent protests following Bolsonaro’s election loss in Brazil in 2022–23

- The growing dependence on digital technology for access to information, services, and connection – a lifeline for some but excluding others who lack access while increasing our vulnerability to disinformation and surveillance

- Increased attacks on environmental defenders and journalists as conflicts escalate over natural resources and territory

- Renewed political conversation and mobilisation about racial justice and the legacy of colonialism, as well as backlash against these discussions

- The rising political visibility of women and their rights, for example in Iran and around abortion rights in the US, as well as sustained political backlash and internal conflict, particularly related to the rights of trans women

- The growing numbers of people displaced by extreme weather and climate crisis

- The extreme consolidation of wealth at the expense of everyone else’s stability and basic needs

In pairs: Scan the news on your cell phone, magazines, or newspapers to identify and share headlines from news sources or announcements by governments or influential institutions such as the World Bank.

Plenary: Share headlines and discuss:

- Do these headlines make sense in relation to your own lives?

- Are similar events, challenges, or changes happening in other countries too?

- What shifts – political, legal, social, cultural, demographic, climatic, technological – are changing day-to-day life and the near future?

- Consider political, economic, legal, social, cultural, demographic, climactic, and technological changes happening in your context: what’s new and different?

The same trend can be both positive and negative. Digital technology, for example, connects us and enables us to expose abuses of power and share ideas globally. At the same time, it makes us vulnerable to surveillance, misinformation, and the mining of our private information.

Small groups: Using flip charts and markers, identify the five key trends affecting your context. Draw and label a graphic to show:

- the five trends your group identified

- the relative influence and potency of each trend (indicated by size on your graphic) in your context

- the connections and overlaps between these trends

- two elements that characterise each trend in your context and globally

Draw or show three examples to explain the activity.

Plenary: Post the groups’ graphics on the wall. For a few minutes, everyone views them. Then each group has a turn to explain two of the trends they identified.

Synthesis: If possible, enlist a resource person to share their insights. Alternatively, share background articles or videos related to the context or geographic region. Some critical trends:

- Authoritarianism, dictatorships, coups, and political extremism

- Xenophobia, racism, othering

- Religious nationalism and fundamentalism

- Ethno-nationalism

- Militarism

- Extractivism and resource grabs

- Climate change and extreme weather

- Backlash and misogyny, anti-feminism, anti-gender

- Corporate capture of the state

- Neoliberalism

- NGO-isation

- Racism and colonialism within organisations

- Rising economic inequity, insecurity, consolidation of wealth

- Repressions and attacks on activists, defenders, civil society, and democracy

Plenary: For each of the main trends that groups identified, invite concrete examples and experiences. Together, clarify the definition, dynamics, and impact of that trend.

- How do we understand or experience the trend in our context?

- How are the trends connected to one another? What historic roots do they share?

- Where can we see examples of communities and movements resisting these trends or offering alternatives and change?

Discuss how people are pushing back against and organising to change the consolidation of power and wealth. For example, as corporations and billionaires concentrate more wealth and wield more political influence, workers are organising, striking, and, in some countries, gaining power in their industries and, importantly, the political process. The push and pull between different interests in highly unequal systems and societies drives the work of movements and other change makers.

Ask: what do these trends mean for the ways we organise ourselves to mobilise and change power?

Download this activity.

What we’re up against

Activists, journalists, and change makers around the world name and describe these as some of the greatest threats to a just and sustainable future. These definitions combine elements from different contexts and readings.

Authoritarianism: Leaders who come to power through elections – including Orban in Hungary, Trump in the US, Duterte in the Philippines – restructure institutions to concentrate power and decision-making within a small elite and pass draconian laws. Often centring a ‘strong man’ ruler, authoritarian governments seek to:

- neutralise the legislatures and media

- rely on the police, military, and surveillance to control information and dissent

- use fear and social division to polarise populations and undermine institutions in order to legitimise taking control

- promise to restore an idealised past and traditions

- use racist, xenophobic, anti-feminist, and homophobic narratives

- put women ‘back in their place’

- demonise immigrants

- align with religious fundamentalist theocrats and cultural conservatives to promote the ‘traditional family’

- limit access to abortion and birth control

- attack LGBTQ+ people as ‘abnormal’

Extractivism: “Extractivism is a nonreciprocal, dominance-based relationship with the earth, one purely of taking. It is the opposite of stewardship, which involves taking but also taking care that regeneration and future life continue.”4 —Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything (2014)

Extractivism usually:

- relies on collusion or complicity – often corrupt – between government, international financial institutions, corporations, and elites

- mobilises security, police, and armies to quell resistance, silence opposition, and detain defenders and rights organisers

- extracts natural resources and lowers wages and standards to produce goods and products at a maximum profit

- devalues women’s labour and caregiving as essential ingredients of unequal and exploitative economies

Neoliberalism: A set of policy prescriptions, promoted by international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and the G8 countries since the 1980s, established the dominant free-market ideology of the late 20th century. These policies include:

- deregulation

- liberalisation of trade

- privatisation of public services

- elimination of subsidies to support local industry and agriculture

- weakening environmental, labour, and other standards

Neoliberalism asserts that private companies and finance with minimal or no government intervention will facilitate economic globalisation and growth. But, in practice, it has led to:

- unchecked corporate power in increased collusion with governments and influence over policy

- obscenely low wages and poor labour standards

- the privatisation and dismantling of social safety nets

- hyper-exploitation of natural resources

- extreme economic inequity

Militarism: Governments increasingly rely on the police, security forces, and the use or threat of violence to resolve social conflict, address crime, and exert public control. They espouse a narrow notion of ‘security’ that centres control of people:

- the surveillance, policing, and silencing of dissent

- attacks on communities, journalists, human rights defenders, and their organisations

- control over populations through fear and intimidation.

As a growing sector of the global economy, and central to US foreign policy, the production and sale of weapons and security technology both for domestic and international conflicts are driving militarism. Investment in the weapons industry and military institutions involves:

- a shift in resources from public services (such as mental health, pandemic preparedness, climate crisis mitigation) to expanding the military and security sector, in collusion with sometimes corrupt and autocratic politicians

- unregulated global business subsidised by public funding, with exorbitant profits, vested interests, and minimal regulation

- a reduction in public safety and an increase in political repression

Surveillance: Governments, large corporations, and organised crime monitor people’s activities and communication and use this information to manipulate, control, restrict, or profit from behaviour. Expanded powers of surveillance – using information and communication technology ‘justified’ by the threat of terrorism – have spawned ‘surveillance capitalism’ by large technology corporations with unparalleled access to data and capacities for tracking people.

Inequity and inequality: Economic and social disparities are created and reinforced by unfair advantages that some have over others. Inequality and inequity are structural, meaning that unfair access to resources and opportunities – such as health care, education, employment, and housing – is built into the social, economic, legal, and political system. Globally, the gap between rich and poor has been growing for decades, further exacerbated by structural oppression based on location and identity (gender, race, ethnicity, class, caste, sexuality, age, ability).

Precarity: Tied mainly to the dismantling and rising costs of basic social services and support and the impact of extreme weather driven by climate change, this refers to the lack of secure or predictable means of survival. Millions of people lack income, employment, land, crops, and housing, leaving them highly vulnerable to destitution. Many workers face precarity due to low wages, long hours, poor working conditions, and the absence of secure contracts or benefits such as health care and child care, or sick or maternity leave.

Crisis of democracy: The validity and strength of democracy as a form of government is being challenged across the world, including inside the US and Europe. Democracy is “a system of decision-making, and governance is exercised directly or indirectly by the people, through a system of legislative, judicial, and executive checks and balances on power.”5 Democratic governance relies on a degree of participation, and this is eroded when elections are manipulated through misinformation, electoral fraud, voter suppression, and violence. Meanwhile, large corporations and other ‘non-state actors’ co-opt elected leaders through campaign contributions, corruption, bribery, and slander. Behind the pretense of democracy, autocratic governments consolidate executive power, reduce oversight, and strengthen ‘security’.

Political and religious extremism: Around the globe, powerful political and religious organisations use religious doctrine to control the public agenda, institutionalise religion in the structures of the state, and consolidate power. Fundamentalist and theocratic groups span many religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, and localised religious traditions such as the ethno-religious Kenyan Mungiki movement and Nepali shamanism. Theocratic and religious political power has grown in recent years with coordinated attacks on ‘gender ideology’ (meaning LGBTQI and women’s rights) claiming they are a greater threat to families and society “than communism and Nazism.”6

Backlash: Refers to the attempts by powerful actors to reverse political, social, economic, and environmental justice gains by dismantling rights and policies that protect more people and the planet. For example, conservative, right-wing, and religious extremists (among others) claim to ‘protect the family’ by reversing new gender and sexual rights and controlling women’s bodies and reproduction. The far-right and fundamentalists are well-organised in many governments and policy processes, including within the UN, and work in alignment with the Catholic Church, evangelical Christians, and the Islamic Brotherhood, for example.

See more definitions in JASS’ Movement-Builder’s Dictionary.

Download handout: What we’re up against.

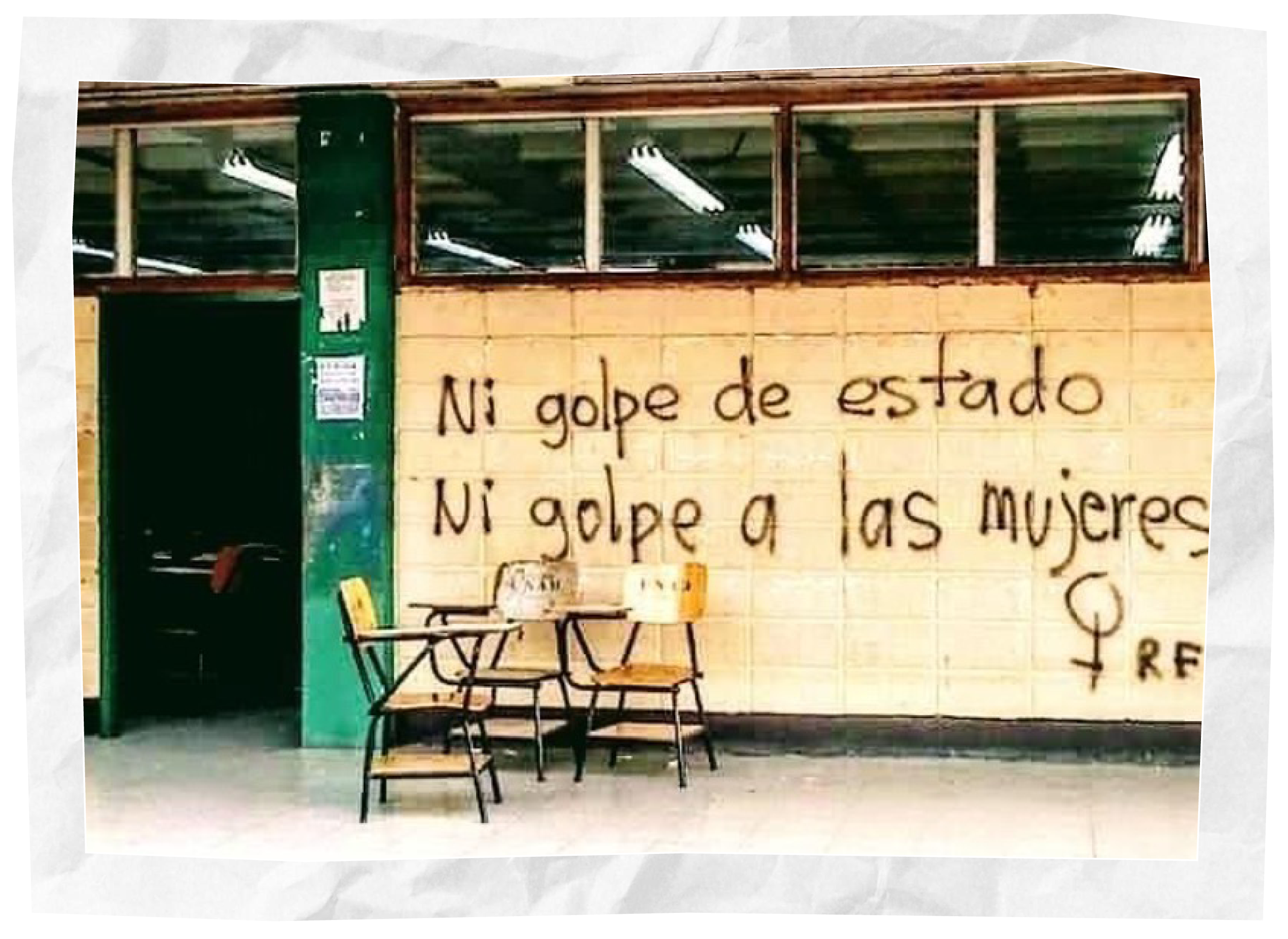

The future is contested

The trends shaping crises and upheaval are, fundamentally, conflicts and contestations over what and who matters, power, resources, and our futures. In the face of multiple crises, people are organising to contest the very foundations of power, mobilising to challenge the political and economic systems that destroy lives and the planet. Even the roles of governments, citizens, and corporations are in question, with different interests and actors pushing to influence or control public agendas, perspectives, and decision-making. What is the nature of this contestation, and what does it mean for our power analysis and strategies?

Activity 3: Territories in dispute

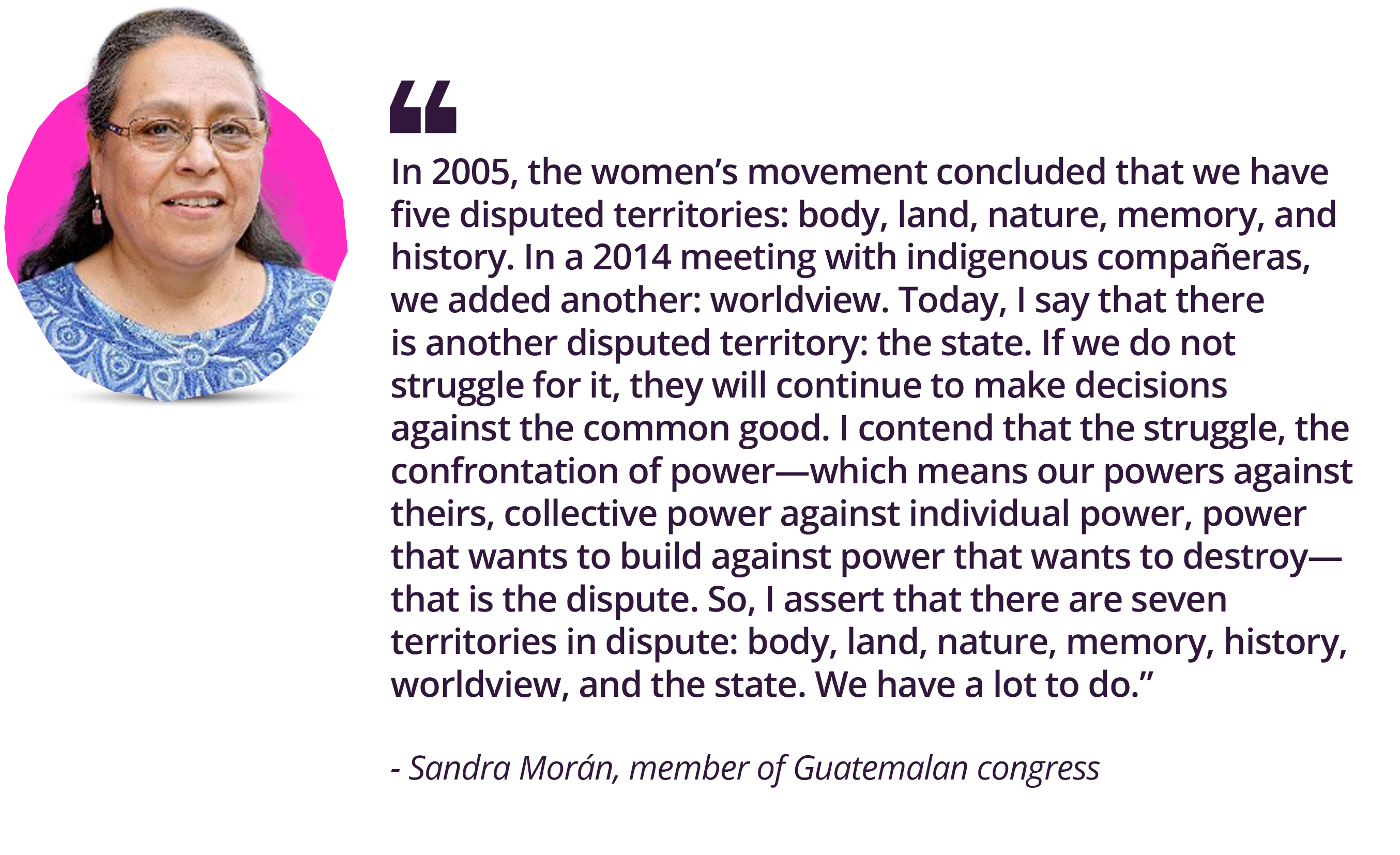

Plenary: Introduce the theme of conflict and contestation as a central dynamic in a time of upheaval. Share the quote from Sandra Moran and read it aloud to introduce the activity.

Small groups: Divide into seven thematic groups. Each group takes a different ‘territory in dispute’: body, land, nature, memory, history, worldview, the state. Discuss:

- From your experience and analysis, identify three or four ways in which this ‘territory’ is in dispute.

- How would you characterise the different sides of the dispute?

- How does this dispute play out concretely in your context? Who and what are on different sides of the dispute? What are their differing interests and agendas?

- What core ideas and beliefs are in conflict?

Plenary: Invite each group to share reflections. Then explore the interconnections between these ‘territories’ in terms of actors involved and the clash of ideas they represent. What do these conflicts suggest for our strategies?

Download this activity.

_____________________________________________________________________________

4 Klein, Naomi, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014

5 From: Power Building: A Shared Analysis of Navigating Crises, Northstar Network, Social Transformation Project, January 2021

6 https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/gender-ideology-fiction-could-do-real-harm

7 Andrea is an indigenous communicator/activist from Guatemala. Reference from the newsletter by Skylight Films written by Pamela Yates.