6

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will learn about the American poet Emily Dickinson and interpret her poem 1562.

You will gain knowledge about feminist and other interpretations of Dickinson’s poetry and her relationship to George Eliot.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet.

Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family’s house in Amherst.

Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.[2]

While Dickinson was a prolific poet, only 10 of her nearly 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime.[3] The poems published then were usually edited significantly to fit conventional poetic rules. Her poems were unique to her era. They contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation.[4] Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality, two recurring topics in letters to her friends.

Although Dickinson’s acquaintances were likely aware of her writing, it was not until after her death in 1886—when Lavinia, Dickinson’s younger sister, discovered her cache of poems—that the breadth of her work became public. Her first collection of poetry was published in 1890 by personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, though both heavily edited the content. A 1998 New York Times article revealed that of the many edits made to Dickinson’s work, the name “Susan” was often deliberately removed. At least eleven of Dickinson’s poems were dedicated to sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, though all the dedications were obliterated, presumably by Todd.[5] A complete, and mostly unaltered, collection of her poetry became available for the first time when scholar Thomas H. Johnson published The Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1955.

Source: Wikipedia

To find out more about Emily Dickinson, watch the documentary about her and answer following questions:

Activity 1

How did Emily Dickinson become a legend?

How did Emily Dickinson become a legend?

How many poems were published during her lifetime?

What was her family background?

What kind of education did she receive?

How is her study of natural sciences reflected in her poetry?

What was her relationship towards religion like?

What was the longest journey in her life?

Which themes were continually occurring in her work?

With whom did she discuss her poetry?

What have you found out about her poems in the documentary?

The characteristics of her mature poetry are pithiness of expression, unusual selection of figures of speech, and the poet’s connecting them into unique lyrical imagery that reflects Dickinson’s precise thoughts, revelations and judgements.

She uses assonance, often times she would write words in capital letters, she also uses her own punctuation, spelling and syntax. Thematically, the poems that the author herself never titled or collected in one book can be divided into categories: friendship and love; poetry, art and imagination; nature: external scenes and deeper meanings; suffering and personal growth; death, immortality and religion.

Many studies are dedicated to the theme of love and friendship, they approach it especially from the point of view of autobiographic writing. Newer studies show that it is possible that the inspiration for many poems came not only from her love towards men, but also towards women (or maybe both sexes), as the poet had, early in her life, many friendships. For instance, she wrote passionate letters to Susan Huntigton Gilbert, a friend, who later on became her sister-in-law. Her love poems are written in such way that it is not possible to identify the gender of the object of the lyric subject’s affection, but they mostly express the belief that a happy union isn’t possible. Some of her poems are addressed to an unnamed women, to “her”. Her nature poems express a descriptive and philosophical string of thoughts; “the first one focuses on portraying beautiful scenes from nature, such as flowers, sunrise, sunset, or a special shade of light which is typical for a specific season or time of day, whilst the other, philosophical poetry searches for the path to the essence of the world and life as such.

As an opposite to the poems that wittingly and humorously portray natural phenomena, we find poems that reveal the dark and suffering side of the poet’s personality. In addition to existential and love themes, Emily Dickinson also tackles social topics which she approaches with a substantial amount of satire.

Read an excerpt from the book The Wicked Sisters: Women Poets, Literary History, and Discord by Betsy Erkkila:

“During the years of literary maturity, Dickinson was particularly drawn to the life and work of George Eliot, whose portrait hung in her room along with those of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Thomas Carlyle (Fig. 4). Beginning with Adam Bede (1859), which was given to her by Sue, Dickinson read virtually all of Eliot’s major works, and her letters are full of fervent and sometimes cryptic exchanges about Eliot’s life and work. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871–1872) was in Dickinson’s view a form of ‘glory’ that had brought Elito ‘immortality’ in time; and Daniel Deronda (1874–76 was “the Lane to the Indes” that offered a kind of earthly and humane sustenance.” (p.83-84)

In 1883 Emily Dickinson read Mathilde Blind‘s life of George Eliot and in April sent a poem to Thomas Niles, the editor of the Roberts Brothers publishing house.

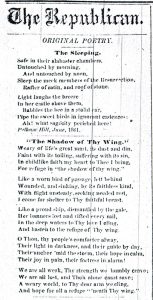

Emily Dickinson: Poem 1562

To Thomas Niles

From ED

April 1883

Dear friend –

Thank you for the kindness.

I am glad if the Bird seemed true to you.

Please efface the others and receive these three, which are more like him – a Thunderstorm – a Humming Bird, and a Country Burial. The Life of Marian Evans had much I never knew – a Doom of Fruit without the Bloom, like the Niger Fig.

Her Losses make our Gains ashamed –

She bore Life’s empty Pack

As gallantly as if the East

Were swinging at her Back.

Life’s empty Pack is heaviest,

As every Porter knows –

In vain to punish Honey –

It only sweeter grows.

Source: Emily Dickinson correspondence

Dickinson also wrote about Eliot in other letters:

“In a letter (L389) of 1873 to her cousins she had said of her, ‘What do I think of Middlemarch? What do I think of glory?’ And after George Eliot’s death on 26 December 1880 Emily had written (L710) to her cousins, saying, ‘The look of the words [stating her death] as they lay in print I shall never forget. …The gift of belief which her greatness denied her, I trust she receives in the childhood of the kingdom of heaven. As childhood is earth’s confiding time, perhaps having no childhood, she lost her way to the early trust, and no later came (L710).’”

Source: http://www.emilydickinsonpoems.org/Emily_Dickinson_commentary.pdf: 474.

Interpretation of the metaphors in the letter: a Doom of Fruit without the Bloom, like the Niger Fig

Collamer M. Abott. explains this line in the letter in his article “Dickinson’s Letter 814″ and quotes Richard B. Sewall, who says the poem seems to epitomize Eliot’s life according to Blind’s biography, which describes a life “far from easy […], especially the earlier years with much of the frustration and many of the spiritual anxieties Emily has suffered through”. Abbott continues: “Suddenly, we realize that ‘a Doom of Fruit without the Bloom’ describes Emily’s own poems: beautiful flowers hidden in a luscious fruit — her poetic life eclipsed. But, if Emily Dickinson is talking about something else that we can guess at only by stretching our imagination, this may be the most sexually charged of all her metaphors.” (Abbott 2001:80)

If you are interested in learning more about Emily Dickinson’s love life, you can find some information here. You can also read a scholarly article by Sylvia Hennerberg. Her relationship toward her friend and later sister-in-law is also depicted in the movie Wild nights with Emily.

Another explanation is offered by Karen Richardson Gee in the article ““My George Eliot” and My Emily Dickinson”.

“The image of the Niger Fig may be related to a phrase in Eliot’s 1871 verse drama Armgart. The main character, an opera singer, has survived a serious illness, but the cost of the cure was her voice. Her doctor, thinking she should be grateful to be alive and still holding out hope that her voice will return, says: ‘Tis not such utter loss. The freshest bloom Merely, has left the fruit; the fruit itself…. ARMGART: Is ruined, withered, is a thing to hide Away from scorn or pity.’ (101) If Dickinson is responding to this image, she seems to say that an important element in Evans’s life has been destroyed. But as the poem enclosed with the letter affirms, Evans’s loss of flower — her childhood — did not destroy her ability to create beauty.”

Activity 2

Interpret the poem. Decipher the metaphors in it. If the task is too difficult, read some of the explanations below first.

Here Losses make our Gains ashamed.

Gee: Because of Dickinson’s perception of Evans’s life as revealed in the letters, the “losses” probably refer to Evans’s loss of faith and loss of childhood.

She bore Life’s empty Pack

Sandra M. Gilbert wrote a thorough study (Life’s Empty Pack: Notes toward a Literary Daughteronomy) about Dickinson’s poem and asks where the striking but mysteries phrases (“A Doom of Fruit without a Bloom”, “Life’s empty Pack”, “In vain to punish Honey) come from. Gilbert argues: “Eliot represents the conundrum of the empty pack which recently has confronted every woman writer. Specifically, this conundrum is the riddle of daughterhood, a figurative empty pack with which – as it has seemed to many women artists – not just every powerful mother but every literal mother presents her daughter. For such artists, the terror of the female precursor is not that she is an emblem of power but, rather, that when she achieves her greatest strength, her power becomes self-subverting: in the moment of psychic transformation that is the moment of creativity, the literary mother necessarily speaks both of and for the father, reminding her female child that she is not and cannot be his inheritor: like her mother and like Eliot’s Dorothea, the daughter must inexorably become a ‘foundress of nothing’. For human culture, says the literary mother, is bound by rules which make it possible for a woman to speak but which oblige her to speak of her own powerlessness, since such rules might seem to constitute what Jacques Lacan calls the “Law of the Father”, the law that means culture is by definition both patriarchal and phallocentric and must therefore transmit the empty pack of disinheritance to every daughter. Not surprisingly, then, even while the literary daughter, like the literaral one, desires the matrilineal legitimation incarnated in her precursor/mother, she fears her literary mother: the more the mother represents culture, the more inexorably she tells the daughter that she cannot have a mother because she has been signed and assigned to the Law of the Father. (Gilbert 1985: 357)

As gallantly as if the East

Were swinging at her Back.

Greg Mattingly states: “When laboring against some adversity under especially advantageous conditions, we may speak of having “the wind at our back,” aiding our efforts rather than exposing them. Here again, in this poem, the particular adversity is an experience of loss, a loss that leaves a feeling of emptiness. Emptiness, implying loneliness, is the hardest of all conditions to bear, the speaker implies, and so paradoxically, the empty pack feels heaviest. Yet She, the subject of this poem, bore it as if the warm wind of freedom were swinging at her back. The word “swinging” as used here is an example of Dickinson’s strikingly original and effective use of common vocabulary. There is a free and easy feeling to this pulsating, assisting easterly wind.” (Mattingly 2018: 67)

In vain to punish Honey –

It only sweeter grows.

Gilbert explains: “Though the ’empty Pack’ of daughteronomy may be heavy, as Dickinson saw perhaps more clearly than they, it is vain to ‘punish’ the cultural ‘Honey’ it manufactures; for the daughter who understands her duty and her destiny, such honey ‘only sweeter’ grows”. (Gilbert 1985: 378)

Further readings

To learn about Emily Dickinson’s reception of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, read chapter 3/II from the book Literary Women by Ellen Moers.

References:

Collamer M. Abbot. Dickinson’s Letter 814, The Explicator, 2001, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 79-80, DOI: 10.1080/00144940109597090

Erkkilla, Betsy: The Wicked Sisters: Women Poets, Literary History, and Discord. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Gee, Karen Richardson. “”My George Eliot” and My Emily Dickinson.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 3 no. 1, 1994, p. 24-40. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/edj.0.0009.

Gilbert, Sandra M. “Life’s Empty Pack: Notes toward a Literary Daughteronomy.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 11, no. 3, 1985, pp. 355–384. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1343361. Accessed 23 July 2020.

Mattingly, Greg. Emily Dickinson as a Second Language: Demystifying the Poetry. McFarland: North Carolina, 2018.