8 Latina/e/o/x Students in Gifted and Talented Programs in K-12 US Public Schools

In the US, the purpose of schooling has been at the center of long-standing debates. Historically, some argue that the purpose of schooling was to serve political ends and the social good while others suggested that schooling was to promote order and control the society at large (Spring, 2016). In many of these debates, the educational needs of gifted children were largely absent. It was not until 1970 that Senate and House representatives voted unanimously for an amendment to the Elementary and Secondary Education Amendments of 1969 labeled “Provisions Related to Gifted and Talented Children” which defined the term “gifted and talented children” and tasked the Commissioner of Education to investigate how the federal government can best support the academic needs of children classified as such.

Fast forward to today’s educational environments: Latine students are underrepresented in gifted education programs (Ramos, 2010). Data from the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) at the US Department of Education reveal that as of 2020, Latino students represent 19.3% of gifted students enrolled in public school gifted and talented (GT) programs, while representing 28.4% of students enrolled in K-12 public schools nationally. On the other hand, White males represent 45.8% of students nationally but 57.5% of gifted students (OCR, 2014). This race disparity in the identification of gifted Latine students is a cause for concern and a reflection of historical precedents that marginalize Latine students at the intersection of race/ethnicity and class. Moreover, a lack of research that disentangles gifted Latine students by racial identity perpetuates monolithic narratives and hinders access to GT programs for all Latine student groups.

Part I: Annotated Bibliography

![]() Brice, A., & Brice, R. (2004). Identifying Hispanic gifted children: a screening. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 23(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687050402300103

Brice, A., & Brice, R. (2004). Identifying Hispanic gifted children: a screening. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 23(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687050402300103

The use of objective assessments such as the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) and achievement tests to capture student intelligence was a common practice in the identification process of GT students. This article describes the relationship between student scores on standardized tests and teacher scores of the behaviors of Mexican American students and their teachers (in rural South-Central Florida). While the study focuses on the strength of nine high mathematical correlations between reading and math scores and teacher checklists for gifted screening identification, it shines a light on math scores for their reduced display of linguistic bias. The author includes an appendix of the teacher screener to allow awareness and sensitivity to the language, culture, and ability of Mexican American students beyond figures when screening for giftedness. The study, however, fails to respond to existing scholarship on the academic achievements, strengths, and needs of Mexican American students, which would be crucial in further understanding giftedness among this community of students. The study, however, does conclude that the underrepresentation of Mexican students in GT programs is due to teachers’ cultural and social perceptions of giftedness.

![]() Gray, A., & Gentry, M. (2023). Hispanic and Latinx Youth with Gifts and Talents: Access, Representation, and Missingness in Gifted Education Across the United States. Journal of Latinos and Education, 23(2), 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2023.2180365

Gray, A., & Gentry, M. (2023). Hispanic and Latinx Youth with Gifts and Talents: Access, Representation, and Missingness in Gifted Education Across the United States. Journal of Latinos and Education, 23(2), 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2023.2180365

Recognizing the diversity between and among different Latine cultural groups, the authors utilize federal data to conduct a descriptive study of GT Latine students. Pointing out every state’s Latine population and percentage of schools with GT programs, the author suggests that Latine students are less likely to attend a school that identifies students as gifted, and, when they do attend schools with identification mechanisms, Latine students are less likely to be identified. While the data spans the nation, the analysis is limited to what schools report. School districts can model this research to do macro-level work around programming policy and access for Latine students.

![]() Harris, B., Plucker, J. A., Rapp, K. E., & Martínez, R. S. (2009). Identifying Gifted and Talented English Language Learners: A Case Study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(3), 368–393. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2009-858

Harris, B., Plucker, J. A., Rapp, K. E., & Martínez, R. S. (2009). Identifying Gifted and Talented English Language Learners: A Case Study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(3), 368–393. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2009-858

Centering a Midwest school district, this case study outlines the policies and practices used to identify gifted and talented English Language Learners (ELL). While the author names changing demographics as a reason to focus on this student population, this section of the article is brief, with limited mention of the ethnic groups from which the students descend. The study grounds data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS) and then provides an in-depth analysis of the school district’s practices as discovered through interviews and policy documents. Interview results highlight how GT students are labeled, how ELL are labeled, and how GT programming is implemented. Interview themes surface barriers such as state support, inaccurate data collection, teaching expectations, and assessment procedures. Although the selected school district was recommended to the researchers by the state because of its diverse community and strong gifted programming, throughout the study, there was no mention of students’ voice as a lever to deepen the research base. This study is a good source for those wanting to start their investigation into how state GT programs go from policy to practice. However, researchers should consider research methods such as Testimonio to center the voices of English Language Learners (ELL) within specific Latine student groups.

![]() Ramos, E. (2010). Let us in: Latino underrepresentation in Gifted and Talented Programs. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 17(4). https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/let-us-latino-underrepresentation-gifted-talented/docview/818559227/se-2?accountid=28932

Ramos, E. (2010). Let us in: Latino underrepresentation in Gifted and Talented Programs. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 17(4). https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/let-us-latino-underrepresentation-gifted-talented/docview/818559227/se-2?accountid=28932

This article defines GT children and then points to a common phenomenon: schooling practices contribute to the underrepresentation of Latine students in GT programs. In particular, the author cites the lack of comprehensive identification measures and programming misalignment to cultural norms as barriers to the GT identification of Latine students. Standardized test scores, fewer teacher recommendations, and limited parent advocacy are mentioned as examples of measures that negatively affect Latine identification in gifted and talented programs. For example, the author suggests that the cultural value of humility in Latino cultures can prevent Latine children from demonstrating their giftedness in school. While the author provides recommendations for improving identification protocols, there is limited discussion on how identification protocols impact different Latine groups (e.g., English proficiency, family composition, immigration experiences, or national origins). Nevertheless, the author highlights organizations supporting this work and alternative strategies to identify gifted Latine students. Non-verbal tests, group-centered performance tasks, and teacher professional development are cited as tools that encourage and include intellectually gifted Latine students. This article is a good resource for educators seeking an entry point into the research surrounding Latine access to GT programs in US public schools.

![]() Stambaugh, T., & Ford, D. Y. (2015). Microaggressions, Multiculturalism, and Gifted Individuals Who Are Black, Hispanic, or Low Income. Journal of Counseling and Development, 93(2), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00195.x

Stambaugh, T., & Ford, D. Y. (2015). Microaggressions, Multiculturalism, and Gifted Individuals Who Are Black, Hispanic, or Low Income. Journal of Counseling and Development, 93(2), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00195.x

In this article, the authors argue that the success of GT students does not hinge solely on identification as gifted but on the students’ experiences in the program. The article describes some of the difficulties GT Latine students face in school because of their giftedness. Using microaggressions as a framework for working with gifted students, the author outlines the relationship between gifted student characteristics and subsequent microaggressions that manifest based on race/ ethnicity, culture, or income level. In particular, the authors suggest that differential behaviors based on culture, experience, and family values lead to educational disconnect for gifted Latine students. The author provides twelve biases that manifest as microaggressions and nine ideas and suggestions that school counselors can take when supporting Latine students.

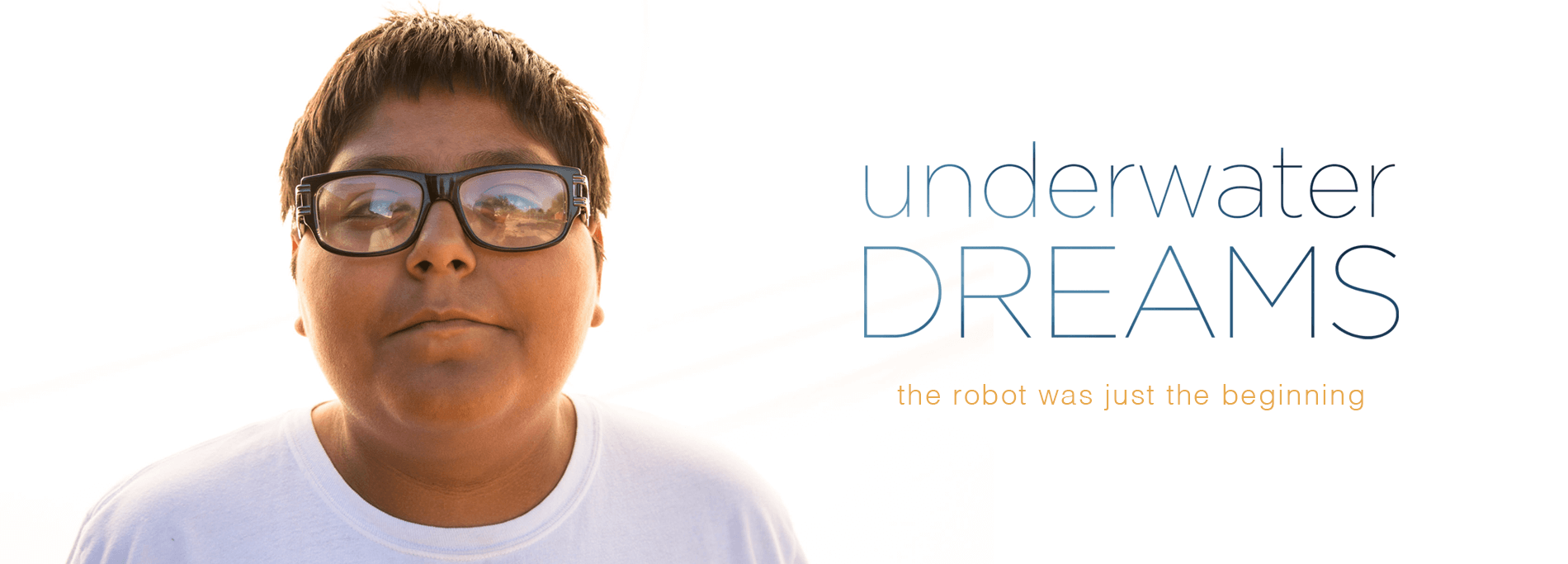

Mazzio, M. (Director). (2014). Underwater Dreams [Motion Picture]. https://www.underwaterdreamsfilm.com/

This documentary explores the story of how the sons of undocumented immigrants learned how to build an underwater robot from Home Depot parts – and defeat engineering powerhouse MIT in a robotics competition. Topics such as immigration, poverty, giftedness, the role of teacher representation, and Latino males in STEM are discussed as the team makes history.

Part III: Policies, Practices, Programs

Iowa Department of Education. (2008). Identifying Gifted and Talented English Language Learners. https://educate.iowa.gov/media/474/download?inline=

The Iowa Department of Education, in collaboration with The Connie Belin and Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted and Talent Development, created a model district manual that outlines how to identify and support English Language Learners who would benefit from gifted and talented programming. Part of the state’s Our Kids initiative, the manual provides practical guidance for understanding and advocating for the integration of gifted English Language Learners.

Sgueglia, K. (2021, October 8). NYC to eliminate gifted and talented school programs that opponents say segregated students. Retrieved from CNN.com: https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/08/us/new-york-gifted-and-talented-education-program/index.html

Published by CNN, this newspaper article focuses on the desegregation policies of the New York public school system, which included the dismantlingof gifted and talented programs. After a lawsuit was filed against the state and city alleging “racial hierarchies” in public education, then-Mayor Bill De Blasio replaced gifted and talented programs with an accelerated instruction program called BrilliantNYC.

Tábora, I, & Institute for Learning & Teaching, University of Massachusetts Boston, “The Talented and Gifted (TAG) Latino Program: Providing holistic support to Boston students in grades 6-12 through programming focused on the development of academic skills, leadership skills and community building” (2013). Office of Community Partnerships Posters. 153. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/ocp_posters/153

Offered to students in grades 6-12, this Boston-based enrichment program partners with the University of Massachusetts Boston to accelerate the learning of Latine and English Language Learner students in Boston Public Schools to succeed in high school and beyond. The Talented and Gifted (TAG) Latino Program provides comprehensive programming for academic and social support.

Interested in Gifted and Talented Programs?

Here are three steps you can take to support students and families

1. Familiarize with Identification Criteria and Policies: Research the specific criteria and processes used by your local schools or districts to identify gifted students. Understanding the requirements, such as standardized test scores, teacher recommendations, and behavioral assessments, will help ensure that students are considered appropriately and equitably.

2. Advocate for Equitable Access: Actively engage in conversations with school administrators and policymakers to ensure that gifted and talented programs are accessible to all students, including those from historically underserved or underrepresented communities. Advocate for practices that promote inclusivity and eliminate barriers such as biases in identification or a lack of resources.

3. Encourage and Support Participation in Enrichment Opportunities: Encourage students to participate in enrichment activities, such as after-school programs, summer camps, or academic competitions, that align with their interests and talents. These opportunities can help cultivate their skills and provide additional pathways into formal gifted programs.

Additional references can be found in the References (by Chapter) section.

We would love to hear from you!

Do you have suggestions on how we can improve this chapter?

Would you like to become a contributor?

We welcome all feedback. Simply complete this quick two-minute feedback form and help us improve our work.

Media Attributions

- The Talented and Gifted (TAG) Latino Program | Project ALERTA © University of Massachusetts Boston's Talented and Gifted (TAG) Latino Program | Project ALERTA is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- King Underwater Dreams © 50 Eggs Films is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license