5 Latino, Latinx, Latine, Latinidades: Beyond Latino Monolithic Myth

This is what our teachers must understand: that language is never neutral. That no matter how skilled we can become in understanding the complexities of language, we cannot forsake the liberating or oppressive power of language.

— Paulo Freire, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970)

By now you may have noticed my use of the term Latine to refer to students whose heritage stems from what we typically refer to as Latin America. You may be familiar with this term. Maybe you find the term affirming, confusing, or even not right. Whatever it is you are feeling at this moment, know that there are likely many others who feel the same way you do and that your feelings may change since the terms used to describe people with Latin American ancestry within US contexts are highly debated, contested, and have changed over time. Debates about the best “term” used to describe groups of people of similar heritage are not unique to the Latine experience in the US. Some argue that debates about the terms we used to describe this population are further intensified for Latines given the inherent and omnipresence of racial, ethnic, language, and cultural diversity and differences across, within, and between Latine communities. Simply put: Latines are not a single racial, ethnic, national, or cultural group. Latines can be of any (or multiple) racial and ethnic groups, speak various languages, have different cultural traditions, national origins, religious beliefs, and political views, as well as experiences with (im)migration and conquest (to name a few).

In this chapter, I briefly describe different terms used to describe people in the US who have Latin American ancestry and offer some insights into ongoing debates that exist regarding the use of these terms. My aim in explaining these terms and debates is to draw attention to the complexities of Latine identities in US contexts, which I argue is fundamentally important for educators to want to understand. Historically and currently, pan-ethnic/pan-racial grouping helps people to identify and connect with shared ancestry, interconnected histories, collective experiences with (im)migration and marginalization in the US (past and present), and most importantly, organizing movements to improve our quality of life (Padilla, 1984). Latines, like other racial and ethnic groups in the US, have never used a single label to describe themselves. Therefore, what I do not do in this chapter is make a definite recommendation on what term is best to use, other than to emphasize the obvious: identity is deeply personal, and all of us benefit from multiple social identities and communities we belong to. What I do recommend is that educator take time to get to know their students and the communities they are part of, and use the terms that are most meaningful and appropriate for the context that you are in. As part of this thinking work, I also provide a brief description of Latinidades, an organizing concept that many find useful in framing the complexities that are integral to understanding and learning from Latine communities.

Current Popular Terms

The terms Hispanic, Latino, Latinx, Latine reflect different perspectives and ways of identifying and referring to people of Latin American heritage. Below I provide a brief description of each term and describe some of the current debates that educators should be mindful of.

Current Popular Terms

The terms Hispanic, Latino, Latinx, Latine reflect different perspectives and ways of identifying and referring to people of Latin American heritage. Below I provide a brief description of each term and describe some of the current debates that educators should be mindful of.

Hispanic:

According to the US Census, the term Hispanic typically refers to a person who is of “Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.” (US Census Bureau, 2024). The term was first used by the US Census in 1980, in response to decades-long advocacy efforts from civil rights organizations, including The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF), that wanted the federal government to improve how to capture information about Hispanic communities to ensure better representation, recognition, and resource allocation for these communities (Lopez et al., 2024; Smith, 2021).

-

Debates:

The term Hispanic emphasizes the Spanish language and culture. As such, one of the critiques of this term is its hyper-focus on the colonial legacy of Spain in the Americas, which includes genocide, enslavement, settler colonialism, and land loss. Many reject the amplification of Spain as part of a pan-ethnic identity; others amplify it. Equally important is that the term excludes the largest and most populated country in Latin America, Brazil. This is because Brazil’s official language is Portuguese, and according to the US federal definition, Brazilians (therefore Brazilians by heritage in the US) are not Hispanic. This is particularly significant because Brazilians are one of the fastest growing Latine groups in the US, particularly in the region where I live (New England) (Borges et al., 2023). Further, the focus on the Spanish language assumes that Hispanics are or should be Spanish-speaking. Yet one in four “Hispanics” does not speak Spanish, even if they wish they did (Lopez & Hugo 2023). In US contexts, schools (and educational policies writ large) coupled with racist xenophobic ideologies, have intentionally prohibited native language use as a tool of deculturalization, which led to many Hispanics becoming monolingual English speakers (Spring, 2021).

As noted in the video below, many “Hispanics” are asking themselves, “Is language crucial to determining identity?” In response to these critiques, in the year 2000, the US Census introduced “Latino” to the Census form as follows: “Is this person Spanish/Hispanic/Latino?” listing Spanish first even though a very small number of Hispanics were of Spanish ancestry relative to the total Hispanic population (Cohn, 2010). By the 2020 US Census this question had been modified to “Is this person of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?”

Latino:

This term typically refers to people (and communities) of Latin American descent. This is perhaps the most popular term used to describe communities with ancestral roots from Latin America.

-

Debates:

There are two major tensions regarding this term. First, historians and geographers have long debated what exactly Latin America is. There is consensus that Latin America includes Central and South America (including Belize, Brazil, Guyane Française, Guyana, and Suriname, all of which are not nations where Spanish is the official language). There are, however, debates about what Caribbean islands, if any, are part of Latin America. Most of the existing scholarship positions islands of the Caribbean whose inhabitants speak a Romance language as part of Latin America because people in these islands have shared experiences of conquest and colonization by the Spaniards, Portuguese, and French (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.). This would include, for example, Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti ( to name a few). Yet other Caribbean nations were colonized by multiple imperial powers, including France, Portugal, and Spain, at varying times (e.g., Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba, and Jamaica), whose official language is not a Romance language. This then leads folks to ask, well, who are Latinos? Is it a sense of location? Shared language and cultural traditions? Or experiences with conquest or imperialism? What groups/nations are part of Latin America? What groups/nations are out? And why? The second major debate on the use of the term Latino focuses on the gendered nature of this term, which I now turn to.

Go Deeper: Young Latinos who don’t speak Spanish are reclaiming their culture after facing shaming

“Young Latinos who don’t speak Spanish are reclaiming their culture after facing shaming.” YouTube, uploaded by PBS NewsHour. October 14th, 2024.

Latinx:

Since the early 2000s, Latinx has been used as a gender-neutral or non-binary term to describe people of Latin American heritage. The use of “x” replaces the gendered ending of “o” and “a” in Spanish and Portuguese. The term first emerged in academic and activist circles to promote the use of greater gender equality and social inclusion between men, women, and non-binary individuals (Fraga, 2021; Smith, 2021).

-

Debates:

The term Latinx has been described as an “elitist” term that is out of touch with the day-to-day realities of the majority of Latines. Survey data from 2024, for example, suggests that only about half of the population that Latinx is meant to describe has never heard of the term and that only 4% of Latine adults say they have used Latinx to describe themselves (Bustamante et al., 2024). Others have argued that the use of “x” is difficult to pronounce and grammatically incorrect in Spanish or Portuguese. Naturally, there are critiques of the critiques of the use Latinx, largely arguing that strict adherence to colonial language rules is archaic and often promotes hierarchies of language use (i.e., use of “proper Spanish” is erroneously tied to questions of class, race, and ethnicity). Languages are also dynamic and always change. Spanish and Portuguese speakers, for example, have adopted African, Indigenous, and English words as part of their regular lexicon that is not part of Castillian Spanish per see but are found in common language dictionaries (e.g., chekear, chicle, fútbol, maiz, monfongo, mondongo, Tegucigalpa, Tenochtitlan, hamaca, rentar, etc.).

Latine:

In the last ten years, the term Latine has emerged in response to critiques of Latinx. Similar to Latinx, the term originated from activists’ communities in Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries who are committed to more inclusive language practices (Call Me Latine, 2021; Cambio Center, 2024). Latine is also a gender-neutral term, but the use of the “e” is more aligned with Spanish and Portuguese linguistic rules, which already use “e” and “es” in many gender-neutral nouns and adjectives (e.g., estudiante or estudante, clientes, triste).

-

Debates:

As this is a fairly new term, the debates are not as fierce (yet). I expect that critiques of this term will be similar to those of Latinx.

Latinidades and Disrupting the Monolithic Latino Myth

Latinidades is a Spanish and Portuguese term that refers to the diverse and multifaceted identities, cultures, and experiences of people of Latin American descent. As described by scholar Juana María Rodríguez, Latinidades largely refers to “the complexities and contradictions of immigration, (post)(neo)colonialism, race, color, legal status, class, nation, language, and the politics of location” experienced by Latines communities worldwide (2003, p.10). In theory, this term acknowledges shared commonalities and differences across many dimensions among Latin American diasporas, emphasizing the idea that there is no single Latine experience (Rúa, 2005). Latinidades, as an organizing concept, has been used to explore Latine communities’ cultural practices, particularly in popular culture, media, art, and activism, focusing on how and why people come together despite their differences. It is important to underscore that the concept of Latinidades has also been criticized. Some argue that Latinidades obscures the unique experiences of individual groups, potentially erasing the distinct identities of Black, Indigenous, and poor people within Latin American communities (Galdámez et al., 2023; Salazar, 2019; Zamora, 2022).

“Yo soy Boricua Pa’que Tu Lo Sepas”

This is not a term but an orientation that requires us to pause and reflect on the terms that we use to describe Latine students and their families. The term loosely means “I am Boricua so that you know.” This phrase was popularized by Puerto Rican hip-hop artist Taino (1995) when he released a song (by the same name) that became an overnight sensation. Since then, the phrase has been widely used by Puerto Ricans to assert our cultural identity in order to counter efforts to render us invisible. This is one of many examples of different communities that would typically be classified as “Latino” or “Hispanic”, demanding to be identified by terms they deemed more appropriate. In essence, this means that there are groups of people of Latin American ancestry who reject all the terms I describe above and prefer to be called by other terms that emphasize parts of their identities they find more meaningful (e.g., Afro-Latina, Dominican, Garifuna, Mapuche, etc.).

Key Takeaways

All these terms are challenged, questioned, and are likely to change, which requires that we critically consider the contexts in which they are used. As educators, it is important that we actively work towards understanding that the terms “hold conflicting understandings….in ways that ultimately call into question the validity of these top-down definitions” (Smith, 2021). The complexities of the terms we use to describe our Latine students are important because they directly speak to the importance of long-standing myths that position Latine communities as monolithic (Díaz & Díaz, 2022). Latine communities are inherently diverse and complex, and it’s up to us as educators to learn from our students, their families, and communities to best understand their experiences. One of the goals of this book is to intentionally challenge us, as educators, to move beyond dominant tropes about Latine students, their families, and their communities. Many of these tropes are deeply grounded in stereotypes and can invite bias into our teaching and learning, educational practices, and policies. We must resist monolithic descriptions of Latine students and instead lean into wanting to learn and understand the complexities of Latine communities.

In my work, I always carefully listen and learn from elders, youth, and everyone in between, and try my best to understand how a community self-identifies, and why they do so, and ultimately try my best to use the most appropriate terms given the contexts that I am in. This often means that I arrive at my work with students, families, and communities con mucho respeto y curiosidad. For example, there are times when I use the terms Latino, Latina, Chicano, Mexican American, Dominican, Latinx, etc., based on the context. As I consider how communities self-identify, my own positionality as an educator, and what terms I will use, remind me of a powerful lesson taught by the master, internationally recognized Brazilian critical educator, Paulo Freire: language is never neutral. As educators, it is our responsibility to seek to understand the complexities of language and labels to address the oppressive power of language (1970).

A full list of references can be found in the References (by Chapter) section.

We would love to head from you!

Do you have suggestions on how we can improve this chapter?

Would you like to become a contributor?

We welcome all feedback. Simply complete this quick two-minute feedback form and help us improve our work.

Media Attributions

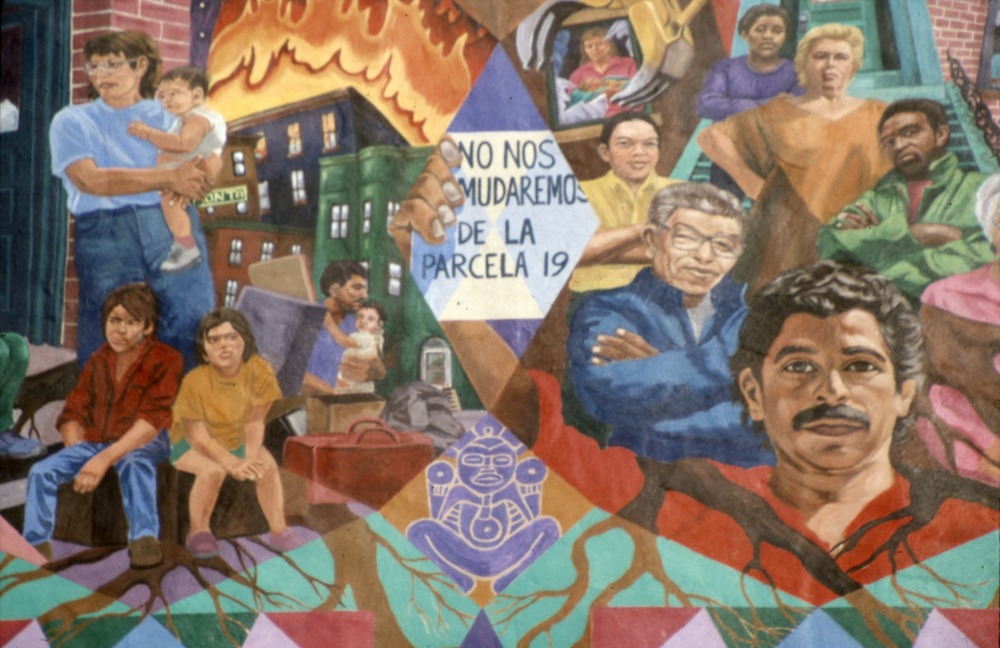

- Detail of “Viva Villa Victoria” Mural is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Puerto Ricans demonstrate for civil rights at City Hall, New York City, 1964 © Ravenna Al is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Defending the Dream Act, 2012 © Edward Kimmel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

to check (English)

Nahuatl word for gum

Soccer but derived from the English work, football

Arawk word for corn

A plantain based savory food [African origins]

"Mondongo" refers to a Latin American tripe soup, particularly popular in the Dominican Republic, Colombia, and Puerto Rico, made with tripe (beef, pig, or goat stomach), vegetables, and aromatic herbs

Capital of Hondoras (Nahuatl)

Orignal name of Mexico City (Nahualt)

Arawk word for hammock

to rent (English)

student in Spanish and Portuguese

Clients in Spanish and Portuguese

Sad in Spanish and Portguese

A term use to describe a person from Borikén, the indigenous name for the isalnd known as Puerto Rico

With great respect and curiosity

“Puerto Ricans demonstrate for civil rights at City Hall, New York City, March 2nd 1964.” World Telegram & Sun. Photo by Al Ravenna.

“Puerto Ricans demonstrate for civil rights at City Hall, New York City, March 2nd 1964.” World Telegram & Sun. Photo by Al Ravenna.