4

Doug Hamilton

Professor

School of Education and Technology

Royal Roads University

Elizabeth Childs

Associate Professor

School of Education and Technology

Royal Roads University

Abstract

This research examines the fit between an institutional learning and teaching framework and the design and delivery of an internationalized graduate-level educational leadership program from the perspective of faculty members. The goal of this research study is to gather faculty perspectives on how the five key pillars of an institutional learning and teaching model were incorporated into the design and delivery of the educational leadership program to Chinese school administrators. This study employs photo-narrative methodology to assist faculty members in expressing their beliefs, opinions, and experiences about designing and teaching in the international program. Other complementary data-gathering methods, including focus groups, graphic recording, and free-writing sessions, are used. Themes are explored that help link the five-pillar model to faculty members’ teaching practices and to their reflections on the benefits of applying the learning and teaching model to an internationalized program context. Recommendations related to faculty development are highlighted.

*

Introduction

The Learning and Teaching Model (LTM) developed at Royal Roads University (RRU) was intended to be applicable to a wide diversity of program models and delivery strategies. Our primary interest in conducting the current research study was to determine how the LTM model “fit” specifically within an international context by exploring the perspective of faculty members responsible for designing and teaching within an internationalized version of a graduate program at RRU—the Master of Arts in Educational Leadership and Management (MAELM) program. In this research, we were interested in what could be learned from faculty members’ perspectives that would be helpful in: (1) understanding the model’s application in an international context and (2) undertaking any modifications to the program for future delivery. This case study has been situated in a larger longitudinal study involving faculty members’ and learners’ perspectives on the program.

We begin this paper by sharing important background information related to the program itself. We also explore the literature on the internationalization of programs that is helpful to our current study.

Program Description and Context

The MAELM program is a 33-credit master’s program designed to help aspiring and existing administrators develop a critically reflective understanding of school improvement concepts and research, and to apply practical tools and strategies to address issues, challenges, and opportunities related to supporting student achievement and growth. The program is based on an outcomes-oriented, cohort-based, and collaborative learning approach that focuses on providing authentic learning experiences that bridge the gap between theory and practice.

The particular version of the international program studied in this research is offered in a one-year timeframe; the first six months consist of RRU faculty teaching in a series of full-time residencies in Beijing, China, while the following six months involve having the Chinese school administrators study at RRU in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

The program is delivered in partnership with the Beijing Municipal Education Commission, the Beijing Institute for Education, and Royalbridge Consulting. Over a four-year period, three successive program intakes resulted in 73 Chinese school administrators graduating from the MAELM program. District representation also increased substantially over the three years with two school districts being represented in the first year, five districts in the next year, and thirteen in the third year. It is also noteworthy that this program won a national “Panorama Award” in 2013, sponsored by the Canadian Bureau of International Education for Leadership and Capacity Building in an international program.

Many of the activities, readings, and assignments within this internationalized version of the MAELM program were customized to respond to the specific needs of the Chinese government to equip school administrators with the knowledge and skill sets to effectively implement the latest wave of national educational reform. The Outline of China’s National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020) is a national policy blueprint that calls for comprehensive educational reforms aimed at building the foundation for a modern learning society throughout China over the next 10 years. The reform strategies, developed in consultation with key stakeholders over a two-year period, involve all levels of education, from pre-school to post-secondary, and recommend significant changes to the ways in which education is delivered, administered, and monitored in China.

Cheng (2005) and Cheng & Tam (2007) have characterized the policy directions in China over the last 30 years in terms of “three waves.” Moving from the “effective schools movement” to “quality school movements,” the system has shifted its focus from improvement on internal processes (i.e. school leadership, professional development for teachers, curriculum development) to external standards and measures of public accountability and quality assurance. Chen and Tam (2007) suggest that the current third wave, “world-class school movements,” focuses on the broader needs of society and that the goals, design, and management of education now must support a 21st century paradigm of learning which emphasizes globalized relationships and world-class standards. When looking to support and prepare educators for this shift in paradigms, the Chinese Ministry of Education supported principals from thirteen municipal areas in metropolitan Beijing to participate in the MAELM international program offered by Royal Roads University.

Research Goals

Childress (2009) notes that with the increasing prevalence of internationalization efforts by universities and colleges, it is important to understand ways to better engage faculty and to determine the strategies and resources that will best support them. As well, Knight (2004) argues that to really understand the process of internalization, it needs to be understood at an individual faculty member or student level. Nevertheless, despite the increased attention paid to internationalization in higher education, little research has actually studied faculty members’ experiences or perceptions in carrying out their roles and responsibilities in an internationalized context (Friesen, 2013; Dewey and Duff, 2009).

The goal of the current research was to address this gap in current knowledge by understanding faculty perspectives on how the five pillars of learning were incorporated into the design and delivery of the Chinese MAELM program. The ‘five pillars of learning’ model was first championed by UNESCO 20 years ago and became a foundational construct in the articulation of the LTM at RRU. Many of the faculty members involved in this program were teaching an internationalized version of a graduate educational leadership program for the first time. We were interested in learning how the five-pillar model aligned with faculty members’ experience in customizing and teaching this internationalized version. Delors (1996, p14) explains:

The commission did its best to project it thinking on to a future dominated by globalization, to choose that questions that everyone is asking and to lay down some guidelines that can be applied both within national contexts and on a worldwide scale.

In a speech at the International Congress on Lifelong Learning, Delors (2013) explained that the pillar model also rejected the compartmentalization of learning into traditional spheres such as school, home, private, and public in the hopes of promoting a more coherent and dynamic model of learning where there is a greater sense of shared responsibility for the fullness of learning that is represented by the model. As a result, we were interested in studying the perspectives of faculty members to learn if their experience in customizing a program for another cultural context reflected some aspects of the transcendence noted above.

Specifically, this research project examined the following questions:

- How do the key elements of the RRU Learning and Teaching Model align with the design/delivery of an international program in educational leadership from the viewpoint of faculty members engaged within it?

- Within the framework of the LTM model, what are the main benefits for faculty members in being involved in the internationalization of this program?

- What were some of the key challenges for faculty? How were these addressed? What issues are still outstanding?

Methodology

The study used an appreciative approach adapted from the Discovery Phase of the Appreciate Inquiry (AI) methodology (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, 2003; Reed, 2007). Consistent with an AI approach, the qualitative research methodology focused on the collection of faculty-generated stories which reflect “what worked in practice” and which were analysed to determine the keys to the success achieved. This methodology is being used in an ongoing study of graduates’ perspectives on the value of their educational experiences in the MAELM program and is described in more detail in Hamilton (2014a).

The study employed a photo narrative methodology to assist participants in expressing their beliefs and opinions about their experiences teaching in the MAELM international program and the alignment of their practice against the institutional learning and teaching model. The approach used a modified version of the visual storytelling method, “Photo-voice” (Wang, Morrel-Samuels, Hutchison, Bell, & Pestronk, 2004; Wang & Burris, 1997). In this particular project, participants shared narratives with the researcher and other participants with the assistance of photographs that they selected from a large photo-bank of images. The goal of using this approach was to enhance participants’ reflective self-expression and engagement in the research process (Warren, 2005).

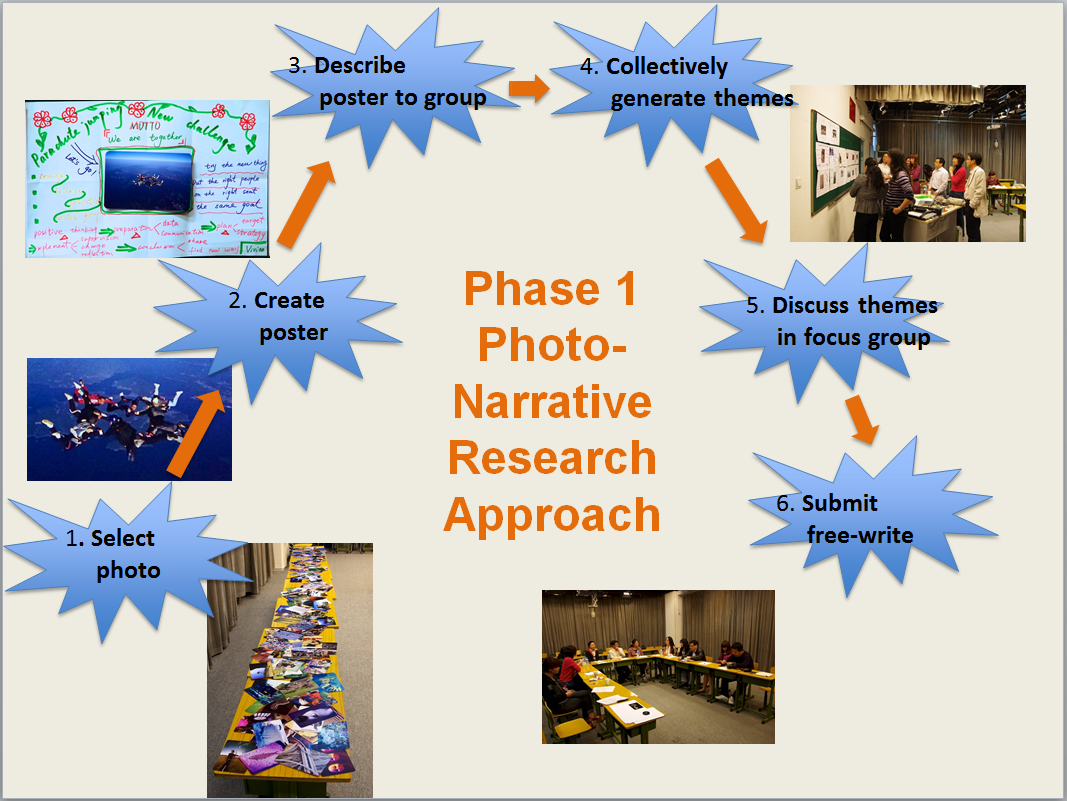

As outlined in Figure 1, the study involved five primary data collection methods:

- Photographs selected by each participant from a large photo-bank (over 300 images) in response to the following question: “Think of your experience teaching in the MAELM China program. Select an image that best describes your teaching experience and how it relates to the five pillars of the RRU learning and teaching model.”

- Posters, created by the participants, that expanded on the symbols or imagery within the selected photo and which helped to explain why the particular photo was chosen.

- Video recordings of participant narratives elicited through the use of a think-aloud protocol (TAP) inviting participants to explain why they chose specific photos and what these photos meant to them.

- A written record that described the generation of collective themes. Participants scanned a “gallery wall” comprised of the posters and then each person was asked to describe a key theme that they believed connected the different posters.

- A focus group discussion and graphic recording of the focus group serving as a wrap-up exploration of participants’ perceptions of common themes explored in the photo-narratives and think-aloud sessions.

Faculty who taught one or more MAELM courses participated in the research study conducted February-March 2014. Of the six faculty that participated in the research study, five had taught at least once in the Beijing residency, three had taught at least once in the in-Canada residency component, with two involved in fully face-to-face delivery and one in a blended delivery course during the in-Canada period.

This paper reports on the thematic data analysis using a formal coding structure derived from the ‘five pillars of learning’ model previously discussed. This was done using an inductive analytical approach and constant comparative method described by Boeije (2002), Huberman & Miles (1994), and Mason (1996).

Findings

Data analysis appears to provide evidence for the following areas of connection to the Royal Roads Learning and Teaching framework (see Table 1). These linkages are discussed below and supporting evidence is shared.

| Themes | The Pillars |

| Learning is Reciprocal & Community-Based | Learning to Live Together Learning to Know |

| Learning as Change or Transformation | Learning to Do Learning to Live Together Learning to Transform Oneself and Society |

| Improving Practice & Changing Perspectives | Learning to Be Learning to Do Learning to Transform Oneself and Society |

Theme 1: Learning is Reciprocal and Community-Based

Data in this theme addressed the participants’ recognition that engaging with course content was only one aspect of a much larger effort to create a meaningful and substantive learning experience for students. For instance, faculty spoke of the shared decision making within the courses and across the program. The co-constructed learning approach, for many learners, was a new “literacy” that required an understanding of its philosophy, orientation, and process. The role of faculty is discussed as becoming cognitive apprentices by modeling reflection, questioning strategies, and through critical thinking (Collins, Brown, & Newman, 1989). Within this theme, faculty acknowledged that the content was just the beginning of the learning experience and that there was a need to encourage space for thinking or “think time”. Faculty spoke of themselves as curators, co-facilitators, and guides in the learning process as well as their efforts to encourage students to consider new ways of thinking about key issues relevant to the course focus. Helping to facilitate the early development of an emerging learning community specific to each cohort was an important step in creating a safe venue for learners to share, question, and discuss ideas.

Supporting an evolving community dynamic enabled faculty to learn from the cohort of students and provide support for the development of the learning community over the course of the program. All faculty participants commented on the delicate balance they attempted to achieve between encouraging the on-going development of community and respecting the inherent culturally-specific approaches and norms around the concept of community, both in the face-to-face and online environments. Faculty members spoke of the shift in their understanding of what counts as a learning experience in what they created for learners and what they experienced themselves. One participant noted:

I was uncertain many of the times whether knowledge was flowing from East to West or West to East. I was uncertain many of the times what was happening there and I was being changed on a constant basis not just when I was face-to-face but when I was online with them and reflecting in private in a way that they were as well.

The Learning to Live Together pillar refers to the development of social and interpersonal skills and values such as respect, empathy, and concern for others. These are defined as “fundamental building blocks for social cohesion, resolving conflicts, respecting diversity, as they foster mutual trust and support and strengthen our communities and society as a whole” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9). Based on this definition, and through the presentation and free-write data, it would appear that this pillar is evident in the work faculty did to create and foster a supportive face-to-face and online learning community in the MAELM program. These qualities and others such as introspection, intuitive awareness, and a collaborative team ethic have also been identified as requirements of facilitators when developing a strong online problem-based learning environment that places learners and faculty as co-contributors to the learning community (Hmelo-Silver, 2004; Hmelo-Silver, Duncan, & Chinn, 2007; Savin-Baden, 2007).

Many faculty members commented on how they worked to find ways to help students have a voice in the learning process and in doing so, had to spend time developing the required supporting skills with learners such as learning how to value and raise their voice and how to undertake critical reflection on, in, and about practice. The concept of the “reluctant silence” (Wang, 2014) was commented on by all faculty as they spoke of the ways in which they were made aware of the need to thoughtfully consider their pacing, placement, and selection of resources, and to make time for learners to become familiar with how to develop their critical thinking skills. The development of the skills and knowledge required to be successful is consistent with the Learning to Know pillar, defined as “the development of skills and knowledge needed to function in this world (e.g., formal acquisition of literacy, numeracy, critical thinking and general knowledge (the mastery of learning tools)” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9).

Theme 2: Learning as Change or Transformation

Data coded in this theme focused on the role of faculty in supporting learner reflection and fostering collegial dialogue in the constantly evolving learning community that was being co-created. Faculty spoke of seeing the program as a learning laboratory where they could try out diverse learning strategies so that the students could experience them and then be able to make decisions about whether they would want to adapt similar practices in their school and if so, how to foster them with their teachers. This appears to be consistent with the Learning to Do pillar which is defined as “the acquisition of applied skills linked to professional success” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9). A participant reflected on this process:

…we worked together to explore what we are learning about learning, I watched the students work so hard to see the similarities and differences between our educational systems, theories, and practices and to identify “the core” – what is most important to keep doing, to stop doing, and to do differently in order to improve student outcomes.

The Learning to Live Together pillar speaks to the development of social and interpersonal skills and values such as respect, empathy and concern for others. These are defined as “fundamental building blocks for social cohesion, resolving conflicts, respecting diversity, as they foster mutual trust and support and strengthen our communities and society as a whole” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9). Faculty also spoke of creating conditions within their courses that permitted the learners to value their own thoughts and ideas. Using the emerging and evolving learning community to create a safe venue for them to share, question, and discuss ideas was identified as critical to developing new ways of thinking about issues and content.

The pillar Learning to Transform Oneself and Society is defined as when “individuals and groups gain knowledge, develop skills, and acquire new values as a result of learning…[resulting in them being] equipped with tools and mindsets for creating lasting change in organizations, communities and societies” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9). Several faculty spoke of the modelling role that they adopted when working with MAELM cohorts because the learning and teaching approach was a catalyst for change across several dimensions of the learners’ experience.

Theme 3: Improving Practice & Changing Perspectives

The focus of the data coded in this theme was on the practice of facilitation as being one of constant reflection as well as the inter-relatedness of the LTM pillars. Within this theme, faculty spoke of being learners themselves and provided examples of the change they underwent as they became more experienced working with the learners and more familiar with the context and challenges the learners faced. These types of comments appear to be consistent with the Learning to Transform Oneself and Society pillar as well as the Learning to Be pillar which is defined as “the learning that contributes to a person’s mind, body and spirit. Skills include creativity, personal discovery, acquired through self-reflection and self-awareness including reading, the internet…” (Royal Roads University, 2013, p. 9). As a participant observed:

teaching in the MAELM Program has reaffirmed my belief that teaching and learning are all about relationships. I have long held this opinion, but it has been made abundantly more clear in this circumstance, where such extreme differences exist between us culturally and experientially, yet there is a common quest to understand each other, from which we all benefit.

For example, many faculty spoke of the time they created, or aspired to create, in their courses for students to actively reflect on the course topics and their applications. Making space and time for learners and faculty to reflect on practice and to think about what and how new learnings might integrate into practice were provided as examples. Several faculty members commented on the act of facilitation in the MAELM program as fostering constant reflection on practice.

Within the faculty teams themselves, many commented that as they worked together to revise, adapt, and refine their practice within and across faculty teams, they too benefited from having a shared sense of community to share, question, and discuss emerging issues. In some cases, this collaborative work led to the transformation of key instructional approaches as noted by the following participant:

I believe the opportunity to work closely with a teaching partner was a real strength of the course delivery in China; team teaching, integrating content from three different courses, combining project-based learning assignments, and collaborative marking.

This is again consistent with the pillar Learning to Transform Oneself and Society, mentioned previously.

Discussion, Next Steps, and Implications

This research study provided opportunities for faculty: (1) to reflect on their own teaching practice based on their recent teaching experiences in the MAELM International program; (2) to reflect on the learning that has come out of this experience; and (3) to enhance their own professional expertise via the sharing of helpful strategies and experiences with other faculty members.

A key finding that emerged is that the five-pillar model appears to apply equally well to faculty members’ sense of themselves as educators and learning facilitators as it does to the design of structures that support the students’ learning experience. We were pleasantly surprised at how well the five-pillar model was aligned with the experiences of faculty members teaching in a cross-cultural internationalized program.

Furthermore, it appears from the faculty perspectives shared within this study that the five-pillar model is robust enough to apply to different cultural contexts. A key to its successful adaptation, however, is for program designers to provide enough latitude in the course design and delivery structure to enable, and even encourage, instructors to play, experiment, and adjust various aspects of the model to fit the specific exigencies of the cultural milieu. Thus, this research highlights the need for professional development opportunities for faculty members that directly support their efforts to develop both innovative and culturally-responsive ways to ensure the model works in practice.

Consequently, this research will continue to inform the support and professional development provided to faculty involved in the MA in Educational Leadership and Management program and has implications for faculty teaching in other international programs at Royal Roads University. In addition, it will help to inform the integration of the RRU LTM into internal processes for program and course design.

Beyond the specific program, this research will assist other program developers at the university in identifying helpful and effective design and delivery practices related to the application of the five pillars of the institutional LTM for other international programs. On a broader scale, this research may be able to provide insight into the role of institutional frameworks of learning and teaching in international program design and delivery, the successes and challenges of their application to the international context, and the level and type of faculty support and professional development required.

References

Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36, 391-409.

Cheng, Y.C. (2005). A new paradigm for re-engineering education: Globalization, localization and individualization. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

Cheng, Y.C., & Tam, W.M. (2007). School effectiveness and improvement in Asia: Three waves, nine trends and challenges. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International handbook for school effectiveness and improvement (pp. 245-265). Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

Collins, A., Brown, J.S., & Newman, S.E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L.B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453–494). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J.M. (2003). Appreciative inquiry handbook. Bedford Heights, OH: Lakeshore Publishers.

Childress, L.K. (2009). Planning for internationalization by investing in faculty. Journal of International and Global Studies, 1(1), 30-49.

Delors, J. (2013). The treasure within: Learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be. What is the value of that treasure 15 years after its publication? International Review of Education, 58, 319-330.

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Paris: Unit for Education for the Twenty-First Century, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0010/001095/109590eo.pdf

Dewey, P., & Duff, S. (2009). Reason before passion: Faculty views on internalization in higher education. Higher Education, 58, 491-504.

Friesen, R. (2013). Faculty member engagement in Canadian university internationalization: A consideration of understanding, motivations and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(3), 209-227.

Hamilton, D.N. (2014a). Making educational reform work: Stories of school improvement in urban China. Journal of International Education and Leadership, 4(1), 1-17.

Hamilton, D.N. (2014b). Building a culture of pedagogical inquiry: Institutional support strategies for developing the scholarship of teaching and learning. Advances in SOTL: The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 1-19.

Hamilton, D.N., Marquez, P., & Aggar-Gupta, N. (2013). Institutional frameworks that support learning and teaching—The Royal Roads University experience. Presented at the Learning Congress, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

Huberman, A.M., Miles, M., & Lincoln, Y.S. (1994). Data management and analysis methods. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative methods (pp. 428-444). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationale. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5-31. doi:10.1177/1028315303260832.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ministry of Education for the People’s Republic of China (2010, July). Outline of China’s national plan for medium and long-term education reform and development (2010-2020) (English version translated by Australian Education International). Beijing.

Reed, J. (2007). Appreciative inquiry: Research for change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Royal Roads University. (2013). Learning and teaching model. Victoria, BC: Royal Roads.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2012). Education for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-sustainable-development/

Wang, F. (2014, March). Empty success or brilliant failure: An analysis of students international learning experience in a collaborative graduate degree program. Paper presented at the Tri Nations Conference, Vancouver, BC.

Wang, S., Morrel-Samuels, S., Hutchison, P.M., Bell, L., & Pestronk, R.M. (2004). Flint photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. American Journal of Public Health, 94(6), 911-13.

Wang, C., & Burris, M.A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education Behaviour, 24(3), 369-387.

Warren, S. (2005). Photography and voice in critical qualitative management research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(6), 861-882.