10

Ining T. Chao

Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching and Educational Technologies

Royal Roads University

Michael C. Pardy

Associate Faculty

School of Business

Royal Roads University

Abstract

Royal Roads University’s classrooms are becoming culturally diverse, giving rise to new challenges and rewards for students learning on teams. Students from different cultures differ in their orientation to communication styles, time, power distance, collectivism and individualism, and task vs. relationship focus. These differences can result in conflict, and can also support success, if facilitated well. In other words, when conflicts arise in teamwork, the emphasis is on creating shared understanding and team norms. Instead of a “your way or my way” mentality for adaptation, RRU faculty and students must jointly invent “our way”. The authors further provide suggestions for modifying team-based learning by adopting an intercultural mindset supported by responsive team composition, intercultural training, teamwork-appropriate assignment design, and multi-dimensional assessment of teamwork. Making team learning valuable and meaningful in a culturally diverse but inclusive manner, with inevitable conflicts, but necessary support and tools for students and faculty to learn and grow, is the very task we need to do to create a productive team-based learning culture.

*

Your Way or My Way?

“I do not like my teammates. I want to change teams.”

“I cannot work with my team. They did not hand in their part of the paper on time.”

“My team members did not contribute at all. I had to do all the work.”

“I contributed but they never took me seriously. They just ignored my points of view.”

“I wanted to contribute. But they don’t let me. They don’t give me any parts to do.”

“They speak so fast. I have a hard time participating. Whenever I tried to say something, I was cut off.”

“They never show me any respect.”

“They speak their own language. I am excluded all the time.”

“Only if my teammates would know how to do team work the way I know it”.

These comments expressed by students about teamwork are examples of the potential conflict that can hinder learning. It seems that members may have different ways of approaching teamwork, influenced by their educational and cultural backgrounds, and the question of “your way or my way?” underlines such conflict. In this paper, we will explore the relationship between cultural diversity and team-based learning, and make recommendations for course design and learning facilitation.

Team-Based Learning and Culture

Team-based learning (Michaelson, Knight, & Fink, 2004; Michaelson & Sweet, 2011) is one of the pillars in Royal Roads University’s (RRU) Learning and Teaching Model (Royal Roads University, 2013). Team-based learning and its pedagogical benefits have evolved with other elements of the Learning and Teaching Model, such as authentic and experiential learning and cohort-based learning, to create a unique teaching and learning culture. We choose the word “culture” intentionally because such an environment comes with a set of rules and expectations, requiring students to commit to team-based learning as an instrument to fulfill the promise for applied learning.

Geertz (1973) defined culture as a system of shared meaning. Gudykunst (2004) extended this definition and stated that “culture is…our implicit theory of [a] ‘game being played’ (original emphasis)” (p.42). In other words, members of a group that follow a certain set of rules and norms belong to the same culture. How Royal Roads faculty come to understand and facilitate teamwork, and how students are expected to learn through teamwork and perform accordingly is the “game” of team-based learning culture. The challenge for students and faculty is to understand and work within the many implicit, explicit, and shifting rules of this game. As the examples at the beginning of this paper illustrated, teams run into trouble when these rules are not clear, or are violated. In addition, our growing international student population embodies an expanded range of cultural norms, worldviews, and communication styles related to teamwork, increasing the likelihood of violations of the rules of the game, at least in the eyes of some. Do students, domestic or international, recognize the consequences when rules are broken? Or more fundamentally, do we need to review and change the rules of teamwork to respond to cultural diversity? How do students learn to bridge cultural differences when conducting teamwork? How can faculty facilitate that learning?

To explore these questions, we examine the foundational emphasis on team-based learning at the university through the lenses of intercultural education. We will describe our experiences, share examples, and offer reflection on this issue. Emerging from our work should be a more culturally inclusive way of conducting team work. This enhances RRU’s team-based learning as espoused in the Learning and Teaching Model. It also takes us closer to the ideal of educating global citizens—a value advocated by Appiah (2008) as an educational and philosophical response to globalization. In short, global citizens are able to view the world as one, working with differences and striving for common goals (Stearns, 2009). With the cultural diversity on campus, all RRU students are getting firsthand intercultural teamwork experience to become global citizens. Authentic and well facilitated teamwork in this context is much more rewarding for both domestic and international students.

Cultural Dimensions that Affect Teamwork

To examine cultural diversity and to make team-based learning intercultural, we need to first unveil the underlying cultural differences that contribute to the challenges in coming to a shared meaning on a culturally diverse team. There is a large body of literature around intercultural communication and diversity training that investigates cultural differences (e.g. Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010; Trompennar & Hampden-Turner, 2012). These cultural differences have been discussed in terms of their effects on team process and outcomes in the workplace, and the argument has been made that diversity does not necessarily produce better results; others have argued that once cultural differences are taken into account and utilized as an asset, a culturally diverse team can produce better results (Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2010; Staples & Zhao, 2006; Gardenswartz & Rowe, 2003). Scholars highlighted several diversity variables that impact teams, including direct vs. indirect communication, polychronic vs. monochronic, large vs. small power distance, individualistic vs. collectivist orientation, and task vs. relationship orientation (Gardenswartz, & Rowe, 2003; Hall, 1977; Hall, 1983; Hoftstede, 2010). In our daily interactions with Royal Roads students learning on teams, we found that an awareness of these five cultural dimensions plays a key role as well because these dimensions are a significant source for friction in teams. With an awareness of these cultural dimensions, students and faculty can better navigate cultural differences on teams.

1. Direct vs. Indirect Communication

Edward Hall (1976) proposed the dimension of high context culture and low context culture. High context cultures value indirect styles of communication. For example, speakers rely less on spoken words to convey meaning and intention because it is assumed the receiver can interpret the message based on their shared knowledge about the situation. On the other hand, low context cultures value direct styles of communication. Speakers use explicit language to express meaning and intention. Misunderstanding can easily occur in teamwork when students with direct styles of communication, while intending to be clear and effective, offend those who are used to indirect styles of communication. Meanwhile, the indirect communicators, who want to be polite and preserve harmony of the group, frustrate the direct communicators. This clash of communication styles can quickly and easily cause friction between team members. For example, when team members are providing feedback to each other, direct communicators may point out the shortcoming of another team member’s work in a very explicit manner. If the team member receiving this feedback has an indirect communication style, he/she may view this explicit and direct feedback as rude behavior.

2. Polychronic vs. Monochronic Time Orientation

People from different cultures view and use time differently (Hall, 1983). Polychronic time orientation refers to the cultures where people tend to view time as a fluid concept—they go with the “flow” of time. Time-based schedule is followed loosely, and changes or interruptions are viewed as a normal part of the routine. It is not necessary that a polychronic individual has a preference for multi-tasking, although it may appear so. “When to do what” is based on what is happening in the moment. Monochronic time orientation, on the other hand, refers to the cultures that set their tasks to a clock. Punctuality and single focus in a given timeframe is the norm for monochronic cultures. Exact time allocated for certain tasks is to be followed. For example, in polychronic cultures, it is more acceptable for a meeting to continue until everyone feels the discussion has come to a natural conclusion. Monochronic people will be more inclined to end a meeting “on time” and attend to the next task on the schedule. When it comes to team learning, the difference in time orientation affects team members’ perceptions about how a meeting is to be conducted or assignment deadlines (Waller, Conte, Gibson, & Carpenter, 2001). A team member may show up late for a team meeting or leave earlier for something else, and this behavior may be viewed negatively due to one’s time orientation. Team members may agree to a deadline for finishing a task, and such an agreement may be interpreted by polychronic team members as a loose guideline. The difference in the perception of time can in turn affect a team’s performance outcomes because the team also has to meet faculty expectations regarding efficient team processes and timely submission of work.

3. Large vs. Small Power Distance

Power distance describes people’s perception toward power distribution, hierarchy, and status in a group (Hofstede, 1991). A large power distance indicates that hierarchy is important and that people communicate and behave according to their roles and status. A small power distance flattens hierarchy. Egalitarian principles are highly valued in cultures with small power distances. In a team learning environment, each student will have his/her own interpretation of how to behave according to roles, as well as expectations about how leadership should be exercised (Zhang, & Megley, 2011). Students from a low power distance culture may expect a less “formal” feel to their team interaction. Exchanging jokes and questioning each other are the norm. For students who come from a high power distance culture, these behaviors may create discomfort as they perceive the team members as not taking things seriously. They may also become isolated on peer teams without orientation to the structure and direction provided by formal leadership, such as from faculty or an assigned team leader.

4. Individualistic vs. Collectivistic Orientation

Another well-researched cultural dimension is the distinction between individualism and collectivism. Individualistic cultures value the autonomy and independence of an individual, whereas collectivistic cultures value interdependence and group identity (Hofstede, 1991; Triandis, 1995). When conducting teamwork, members’ collectivistic or individualistic orientations can come into play when prioritizing and negotiating roles, responsibilities, and rewards (Wagner III, Humphrey, Meyer, & Hollenbeck, 2012). In an individualistic environment, students from cultures that value a higher degree of interdependence have limited social networks from which to draw support for learning and success. The lack of support can also negatively impact loyalty to team processes and outcomes.

5. Task vs. Relationship Orientation

Cultures also differ in ways of managing relationships. Some cultures place a stronger emphasis on harmonious relationships over task completion. (Adler, 2002. p.64; Gardenswartz and Rowe, 2003). Teamwork is ripe with opportunities for cultural conflict when it comes to competing priorities of relationships and tasks. Team members may limit constructive criticism for fear of damaging team relationships. Task-orientated members may just want to “get down to business,” while the relationship-orientated members want to invest time building trust in the process. Relationship-oriented members may be perceived as delaying the progress of the teamwork by focusing on the social processes.

These cultural dimensions can interfere with the development of deep-level relationships within a team, potentially negating the high quality outcomes of successfully managed diversity. Of course, these cultural dimensions also play out against the backdrop of the cultural preferences of the university and the wider Canadian society. For example, we expect students and faculty to engage in teamwork with more direct communication, including in conflict situations. The faculty encourages students to bring issues to their attention early, and they see early and direct intervention as a better strategy. With regards to individualism vs. collectivism, students are rewarded for self-reliance and initiative. Even though most team members exhibit a desire to work with others, specific constraints apply. For example, teams commonly divide assignments into roughly equal tasks that are then completed independently by individual students. It is expected that this work be completed with limited to no support from other team members or faculty. Students are expected to resolve challenges in completing the task on their own and without prompting by others. These expectations favour the individualists in a group and put collectivists in a disadvantageous position from the start. Also, throughout this process, it is expected that students will adhere to deadlines. Faculty expects the work to be completed on time—failing to do so will result in penalty. The academic culture at Royal Roads reflects wider Canadian social norms; we need to help students and faculty become aware of these norms. By doing so, we open the door for mutual understanding between larger scale cultural characteristics as well as between these cultural characteristics and the culture at Royal Roads.

Becoming Intercultural

Cultural diversity can increase productivity, creativity, and innovation (Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999; Mcleod, Lobel, & Cox, 1996) by bringing more ideas to the discussion and stimulating thinking. Diversity can also increase conflict, posing danger to the efficiency and effectiveness of teams. To achieve the potential benefits of cultural diversity in team-based learning, special attention needs to be paid to integrating intercultural processes into teaching and learning. In other words, putting people with diverse cultural backgrounds on a team is only the first, and an insufficient, step to bridging cultures. Teams are more successful when members have the support and skills to negotiate the dynamics and processes that are affected by cultural differences; support and development of skills require active intervention from faculty and culturally inclusive course design.

Our guiding view is that learning on teams is a complex activity with emergent and unstructured properties that create uncertainty for both faculty and students. This view is distinct from cause and effect models of teamwork, which can be summarized by this formula:

In much of the literature on teamwork, attributes (i.e., group size, cultural diversity, leadership), processes (i.e., decision making, managing conflict, communicating), and context (i.e., organizational environment, purpose) are seen as inputs that, when properly integrated, result in successful outcomes (Gunter & Stahl, 2010; Salas, Sims, & Burke, 2005). The logic is that teams are successful when attributes and processes are aligned with the context.

Instead, we argue that the relationship between attributes, processes, context, and outcomes is synergistic, connected in complex, non-linear feedback loops. As a consequence, we recommend that faculty consider both sides of the relationship when supporting intercultural teams. So what do faculty need to consider to ensure cultural diversity is an asset and not a liability to team success? There are no prescriptions; instead, students and faculty must work together to construct a rich culture of team-based learning in which everyone is valued. We accomplish this by probing and acting, and based on what our senses tell us and what information emerges, responding appropriately (Kurtz, & Snowden, 2003). In this way, teams and faculty co-create meaning, give shape to their work, and texture to their processes. Each team can develop a unique culture, where differences can be recognized and negotiated, and create opportunities for cohesion and creativity.

From the perspective of complexity, there are any number of methods and tactics for supporting teams. We have chosen to pull on five threads from both sides of the teamwork tapestry: training and support, composition, design, assessment, and technology. Through this loose tapestry, we highlight current and successful practices, and point the way to more culturally sensitive and inclusive team-based learning.

Training and Support

Working with others is a learning outcome in and of itself at Royal Roads. This suggests the need for specific learning about teamwork. Across campus, team training is provided in a variety of forms and formats, from stand-alone workshops for entire cohorts to one-on-one coaching for teams or individuals. At the International Study Centre, team workshops are an integral part of orientation and foundation programs. Cultural sensitivity is a component of this program, highlighting differences in cultural dimensions and providing students with tools to engage in intercultural teamwork. In 2014, the university established the Student Coaching Centre within the suite of services offered by Student Services. As part of its mandate, the Student Coaching Centre has responsibility for further improving the equity and fairness of access to supports for teams across the campus.

Regardless of the form and format, the growing cultural diversity of the university suggests that cultural diversity training should be strengthened and added to existing and new team training programs. Cultural diversity will continue to increase at Royal Roads due to internationalization. We cannot assume that the presence of multiple cultures will lead to intercultural team skills. Below is a poignant reminder:

Were it the case that contact alone generated [intercultural] competence, citizens of neighbouring nations would be particularly good at communicating with one another, and native-born members of national groups would be particularly adept at understanding immigrants to their countries. What we see, of course, is usually the opposite (Bennett & Adelphi, 2001, p. 2).

As Bennett and Adelphi highlight, intercultural contact often leads to conflict. In addition to encouraging multicultural contact at Royal Roads, we must also cultivate an intercultural mindset. An intercultural mindset includes the recognition of cultural differences, the maintenance of a positive attitude toward these differences, the ability to identify potential areas of conflict and appropriate compensating strategies, and the acknowledgement that there is much to learn from and through cultural differences (Bennett & Adelphi, 2001). Such openness to differences and a strong desire to learn through the experience has been proven to enhance team performance (Pieterse, Knippenberg, & Dierendonck, 2013; Homan et al., 2014). In addition, there is power in naming; it is important to help students articulate cultural biases and assumptions. In this naming, students may be better able to appreciate the rewards of intercultural teamwork, and also its challenges. Training can deepen cross-cultural understanding and facilitate the development of shared mental models necessary for team success (Staples & Zhao, 2006; Bolman & Deal, 2003).

We suggest that it is not enough to assume that international students simply adapt to the team culture at Royal Roads. The expectation that “they should adapt” simply ignores the many assets our international students bring to our learning community, and diminishes opportunities for our domestic students to hone their intercultural skills. Our learning community’s commitment to social constructionism suggests that the culture of all our students, not just the dominant Canadian culture, has a role in determining the specific shape and texture of team culture. This can only happen when we acknowledge the diversity of our classrooms and actively work to surface the rewards and challenges of that diversity.

A paraphrase of Edgar Schein’s (1999) Process Consultation Model nicely summarizes our views on training and support (p. 655-656) for intercultural teams:

- only students “own” the problems and successes of teamwork in the classroom;

- students are not experts on what kinds of help to seek—faculty and others at the university can provide helping theory and practice;

- most teams want to learn and improve—they need help in determining what to improve and how to improve;

- most teams will be more successful if they learn to diagnose and manage their own diversity; and

- only students will know what will ultimately work in their team.

Composition

Culturally diverse teams perform better overall but are slower to get started and need more support at the start. When we evaluate diversity based on the cultural dimensions discussed earlier, the degree of homogeneity or heterogeneity that should be implemented in a team to achieve desired pedagogical outcomes becomes an important consideration. Course designers and faculty can accommodate cultural diversity in teams by adjusting team composition to reflect the skills and ability of students. The research on composition suggests that culturally homogeneous teams (Johnson & Johnson, 2009; Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2010) are more successful than culturally diverse groups in the early stages of working on teams. Team members with limited team experience will find culturally homogeneous groups easier to navigate. Members of culturally homogeneous groups are more likely to share baseline assumptions about teams and teamwork, which help shape group norms and enable them to function successfully with greater levels of implied knowledge (Staples & Zhao, 2006; Van den Bossche, Gijselaers, Segers, Woltjer, & Kirschner, 2011).

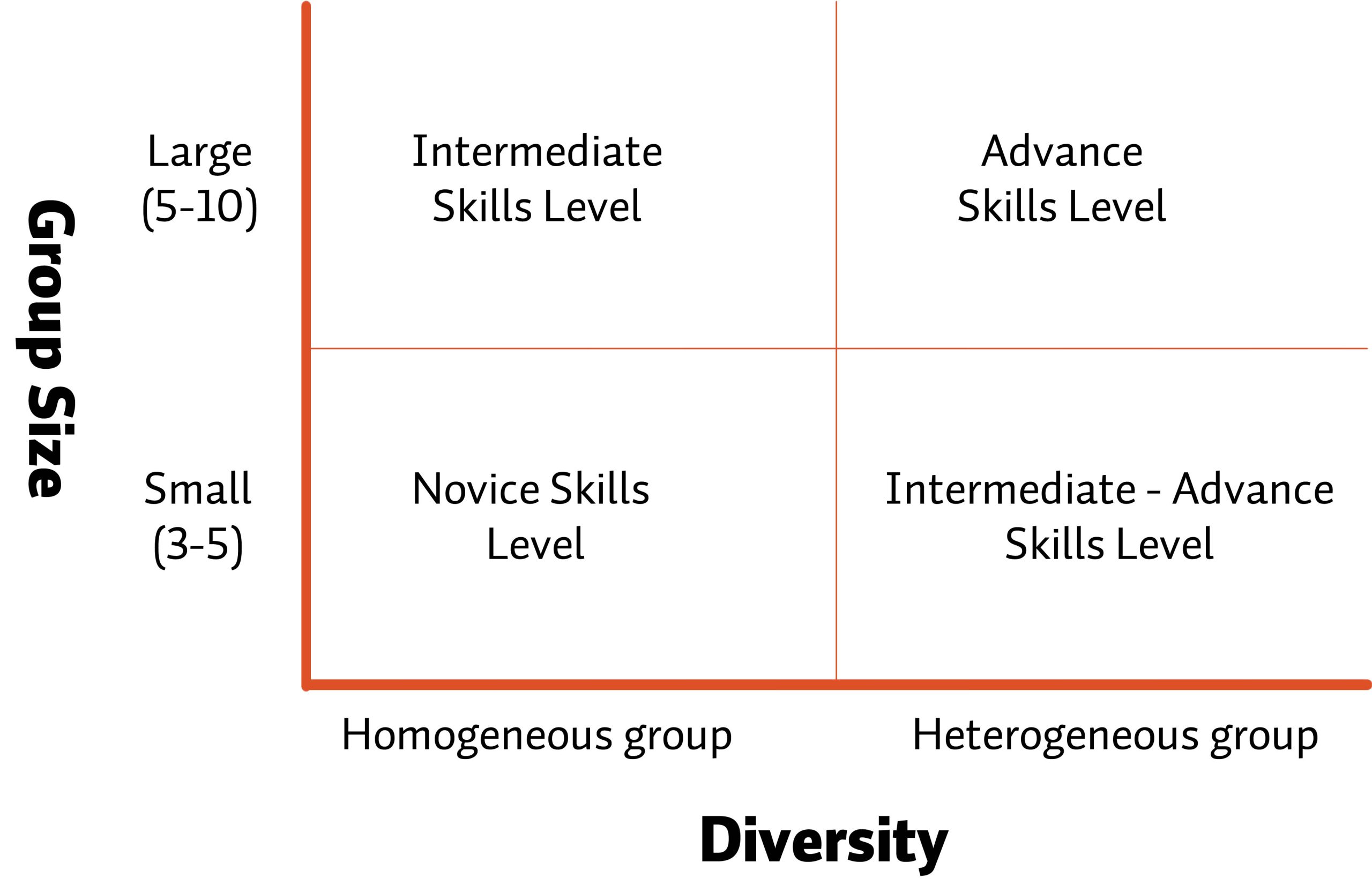

In support of managing composition, we encourage faculty to determine team membership rather than leave it up to students. There is no simple formula for managing team composition; rather, faculty must exercise judgment when establishing teams and help teams monitor their success. At the International Study Centre, newly arrived undergraduate international students, facing initial cultural shock, can find comfort in working within culturally homogeneous groups and support for their mental models; homogeneity can foster team cohesion. When they are put into teams, this support and comfort is taken into account and weighted against the need to learn how to work with culturally different others. With graduate students in international-domestic mixed classes, team composition may be highly heterogeneous from the outset as the mature students can better deal with stress from cultural shock and rely on newly established friendships with cultural strangers. Overall, the emotional, social, and cognitive security of homogeneous teams must be balanced against our pedagogical objective of successfully learning and working on culturally diverse teams (see Figure 1 below).

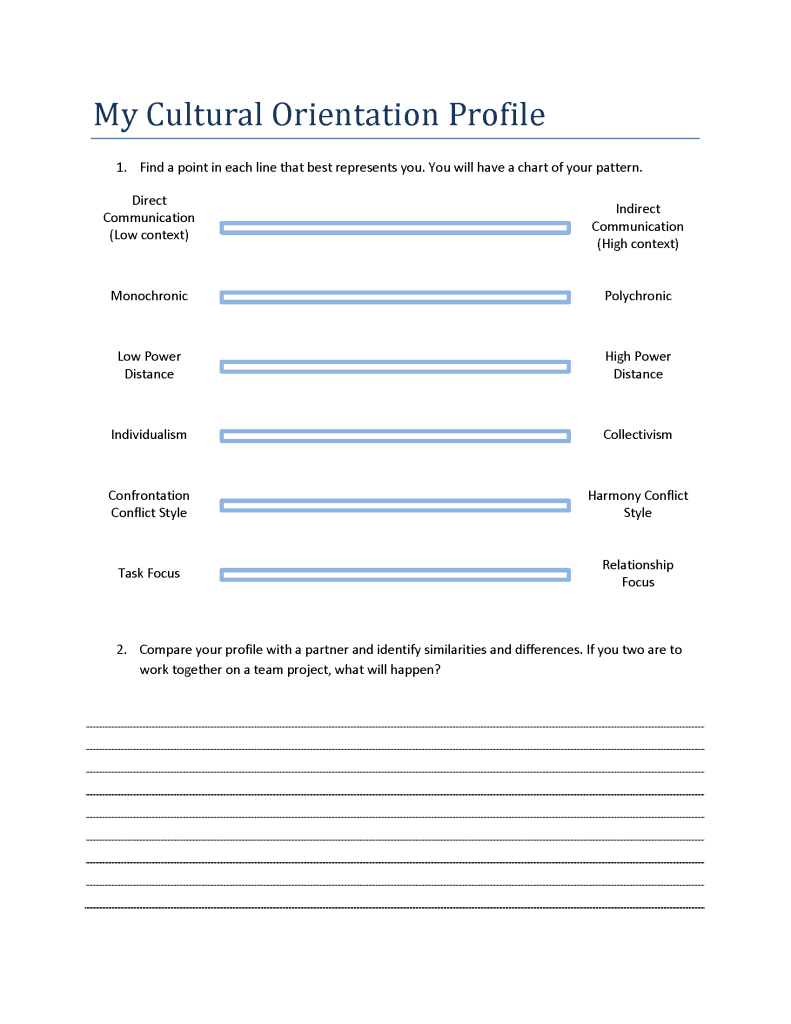

In the spirit of viewing teamwork as a complex system, we encourage faculty to consider homogeneity and heterogeneity of team composition as a polarity (Johnson, 1996), rather than a binary either/or choice. The tension between “sameness” and “different” is ongoing over the life of the team. They are interdependent, and only understood in the context of the other. As a result, we prefer teams to explore the opportunities in difference and sameness, thereby better understanding the subtleties, rewards, and challenges of intercultural teamwork. One tool that can raise students’ awareness and help them explore the sameness and difference is a Cultural Orientation Profile used in RRU’s team training workshop (Figure 2). Students self-identify and discuss the potential impact of cultural orientation on their teamwork. The conversation with team members to compare their cultural orientation profiles helps them to better understand and appreciate each other.

Design

We can further support the success of intercultural teams by designing meaningful team activities. Often, we take simple tasks, such as writing a short case study, and ask students to sort out the divisions of work necessary for teamwork. Unfortunately, this is like asking three or four people to move a single chair out of the room; it is a task more easily performed by one, maybe two people. The task is made simpler by the division of labour, thus discouraging cooperation, coordination, and collaboration. To extend the analogy, we need to design large, heavy furniture for teams to move so that real and meaningful teamwork is possible (Schmidt, 2011, pp 7-9). Implicit in this argument is the view that the artifact of teamwork is not exclusively the outcome of team attributes, processes, and context, but also an input; the artifact shapes and patterns the work of teams. Moving a heavy table requires the movers to adopt specific leadership, communication, and coordination strategies to address the interdependencies inherent in the task.

For example, many courses ask teams to write up a case study. This usually takes the form of an essay and/or an audio-visual presentation. Teams often choose to divide the deliverable into equal parts (e.g., “You write the introduction, I’ll write the analysis,” “I’ll do slides six through nine”). Without changing the case, we can encourage alternative divisions of labour. For example, in one BA of Commerce course, team members are asked to adopt different roles in relation to a case by considering the situation through the lens of multiple stakeholders, and to respond to the case through the lens’ of these stakeholders. In a BA of Professional Communication course, teams are asked to construct a number of artifacts (i.e., essay, PowerPoint, website, and/or video) around a single assignment. Heavy assignments allow students to specialize within the project, develop discrete skills, and bring unique information and knowledge to the team. As a result, team members are mutually dependent, and therefore responsible for each other. Great team assignments require teamwork; assignments better suited to individual work should be left to individual students.

More generally, we can further encourage meaningful teamwork by asking members to take on distinct roles within the team process and present a portfolio of work. Instead of focusing on the artifact, members can be assigned wider roles common to project and collaboration work such as observer, facilitator, researcher, stakeholder, customer, writer, and/or editor. The resulting portfolio of work allows for a wider range of skills and abilities, accommodates a greater diversity of cultural orientations, and acknowledges the reality of teamwork in organizations. Students in the MA of Leadership are often encouraged to adopt this approach to team assignments, especially in the two on-campus residencies.

The design of teamwork has an impact on the success of student teams. In order to be meaningful, assignments must provide opportunities for learning about teamwork and student success. Assignments should allow for cultural diversity; this suggests that culturally meaningful assignments should encourage teams to use their inherent diversity in the construction of the artifact (Bardram, 1998; Schmidt, 2011). For example, in one Master of Global Management course, a team assignment specifically asks students to explore cultural differences to key issues such as gender, corruption, and power. In this assignment, the cultural diversity of the team is an asset because of the unique knowledge students from different cultures bring to the discussion. The outcome is that we all become more conscious of our own stereotypical beliefs. A well-designed team assignment “makes simple division of labour difficult, promotes interdependence, broad-based participation, and the use of varied cultural perspectives…” (De Vita, 2005).

Assessment

In addition to designing culturally meaningful team assignments, we should also assess assignments not only on the finished product, but also on the process. If we accept that teamwork is a discrete outcome embedded in every course at Royal Roads, then we should also be assessing that outcome. It is fair to say that across the university, teamwork is assessed, but often only according to one of its measures.

Team success can be understood through the three lenses of performance, satisfaction, and efficiency (Li, Cropanzano, & Badger, 2013). Performance is the standard measure of team success at the university. Performance is the measure of the quality of the team artifact (outcome), usually in the form of an alpha-numeric grade. Satisfaction is the measure of the individual and collective judgment of the team about the process and the outcome. Efficiency is the measure of the relationship between effort, usually understood in terms of time, and the satisfaction and performance of the team. From these provisional definitions, we understand that performance, satisfaction, and efficiency are overlapping measures. Mental models of success vary across cultures and individuals. Few students would dispute an “A,” but family and career expectations, experiences at previous educational institutions, cultural measures for achievement, and other factors clearly play a role in a student’s understanding of the overall success of their team and its work. Dissatisfaction with teamwork is often framed in terms of equity and fairness, as the samples of dialogue at the beginning of this paper illustrate. When there is a gap between student expectation and team performance, issues of fairness and equity frequently surface. Opening up assessments to satisfaction and efficiency provide greater insights and opportunities for understanding performance, and how to continue improving.

Focusing on team performance provides an incomplete measure of the success of the team and a limited understanding of the complexities of working with others. We need to add to our range of teamwork assessment tools to help students measure, adjust, and develop their teamwork. One proven tool is guided peer assessment. Peer assessment allows members of a team to hold each other accountable, helping to address perceived and real issues of inequity and unfairness. Various methods for peer assessment are used across the campus. Some faculty use peer assessment tools to help students and teams gain insights into their strengths and weaknesses. Mostly, these assessments are used to provide formative feedback to student teams and are not tied to performance measures. In the BCom program, one faculty member is experimenting with formalizing peer assessments and using them to adjust team grades in an attempt to better reflect the experience of students in their final grades.

Teamwork is a foundational learning method and an outcome; as with other methods and outcomes, it must be tailored and adjusted to the skill and ability of the students, as well as the expectations of the faculty. This suggests a developmental approach to teamwork; start easy and small with lots of support, and build toward harder and larger projects while at the same time slowly removing the safety nets. One important piece to this progression is to provide specific, realistic, and relevant feedback about a team’s work, not just the artifact they create.

Faculty must intervene to increase the “collective capacity and performance of a group or team through application of…assisted reflection, analysis and motivation for change” (Clutterbuck, 2014, p. 271). The value of a coaching stance toward student teams is that it promotes shared meaning making and redistributes power between faculty and team members. For example, in a traditional educational role, faculty will recognize and reward team performance. In a coaching role, faculty help students explore influences on team performance by using tactics such as self and peer assessments that can help members understand their impact on team success. In some of the courses in the Year 1 foundation curriculum at the International Study Center, students complete a self-assessment worksheet at the conclusion of their teamwork to answer questions such as “what have I learned about working in teams?” and “how can I improve my team skills next time?” Subsequently, faculty debrief students’ responses to these questions and coach them to further develop their capacity to work in intercultural teams.

Technology

Technology can be used to improve communication, to improve the depth of interdependence in intercultural teamwork, and to hold students accountable to others. The immediacy of face-to-face teamwork can be challenging for culturally diverse teams. We have shown previously that individuals from different cultures sometimes miss and misinterpret nonverbal cues, potentially resulting in conflict. These incidents are often exacerbated by linguistic inequality. Asynchronous communication technology such as forums on learning management systems can improve dialogue by slowing down and filtering the flow of information between team members (Carte & Chidambaram, 2004; Palsole & Awalt, 2008; Staples & Zhao, 2006). For example, in one course, on-campus students practice dialogue in both the classroom and online through Moodle forums. The online practice models important components of dialogue such as active listening, taking turns, asking clarifying questions, and building on ideas.

Technology can also be used to coordinate teamwork. Part of the challenge facing teams is coordinating individual activities that collectively result in the artifact of their efforts. Currently, in the Faculty of Management, teams are asked to complete a Team Assignment Plan Summary, which documents roles, responsibilities, and deadlines. Many students recognize the value of the process and the document in their success. Unfortunately, it is hard to keep these commitments front and centre within the team as it is a MS Word document easily buried by more recent work. Many of the elements of this document reflect a project-based orientation to teamwork. There are several online and open project management software programs that mimic and build on the basic elements of the Team Assessment Plan Summary document, but also provide a single platform for organizing responsibilities, roles, and schedules; most have the added advantage of allowing for multiple and overlapping projects, allowing teams to better visualise the totality of their team enterprise and to more precisely mark time, a key element for understanding team efficiency. Better visualization and coordination of teamwork can help overcome cultural orientations to time, tasks, and responsibilities, and help develop a shared understanding of expectations between team members.

Going Forward – Our Way

The opening scenarios posed the question “Your way or my way?”—highlighting the tension and conflict in intercultural teamwork. We want to provide an outlook for integrating cultural diversity into team-based learning at Royal Roads. Several pedagogical considerations have been proposed and good practices will continue to emerge in the context of the internationalization. It is important to keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Effective and innovative pedagogy in this area will rely on faculty’s own intercultural awareness, reflection, and application of intercultural competence in designing team assignments and facilitating students’ teamwork. Only with the intentional integration of cultural diversity into team-based learning can students practice and develop meaningful intercultural team skills. What we need to avoid is the opening scenarios being the only outcomes of team-based learning in an intercultural context.

The outlook for meaningful intercultural teamwork lies in devising an “our way” of collaboration at Royal Roads. We need to put efforts into guiding student teams to develop shared values and mental models (Meeussen, Schaafsma, & Phalet, 2014) as the foundation for intercultural teamwork. To be successful in this regard, cultural differences need to be recognized; students and faculty alike need to assess their own standing on the cultural dimensions discussed earlier. We also need to be aware of the overall Royal Roads teamwork culture as it manifests in practices such as team coaching, team performance review, and the Team Assignment Plans Summary.

With a better cultural mirror reflecting on our own individual and institutional culture towards team-based learning, we can ensure that using team-based learning principles is about bringing together team members’ different understanding of the world, different ways of solving problems, and different ways of acquiring knowledge. (Gentner & Stevens, 2014, p. 3 ). Students develop positive attitude towards working with others and attain valuable collaboration skills when intercultural teamwork is designed well with students’ intercultural competence at the centre of the learning outcome and assessment (Deardorff, 2006; Montgomery, 2009).

Extending the Geertz and Gudykunst definition of culture, Schein (2010) described culture as a “pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, which has worked well enough to be considered valid, and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” (p. 17). Within the context of Royal Roads’ internationalization, the “adaption and integration” is something we need to turn our attention to in order to inter-culturalize our team-based learning within the wider framework of the Learning and Teaching Model. Making team learning valuable and meaningful in a culturally diverse but inclusive manner, with inevitable conflicts but necessary support and tools for students and faculty to learn and grow, is the very task we need to do to create our way.

References

Adler, N. (2002). International dimensions of organizational behavior. Montreal, QC: McGill University.

Appiah, K. A. (2008). Education for global citizenship. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 107, 83-99.

Bardram, J. (1998, September). Designing for the dynamics of cooperative work activities. ACA4 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Seattle, WA.

Bennett, M. J., & Adelphi, M. D. (2001). An intercultural mindset and skillset for global leadership. In Leadership without borders: Developing global leaders. Conference proceedings of the National Leadership Institute and Center for Creative Leadership, Adelphi, MD: University of Maryland University College.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2003). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Carte, T., & Chidambaram, L. (2004). A capabilities-based theory of technology deployment in diverse teams: Leapfrogging the pitfalls of diversity and leveraging its potential with collaborative technology. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 5(11), 4.

Clutterbuck, D. (2014). Team coaching. In E. Cox, T. Bachkirova, & D. Clutterbuck (Eds.), The complete handbook of coaching (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Vita, G. (2005). Fostering intercultural learning through multicultural group work. In J. Carroll, & J. Ryan (Eds.), Teaching international students: Improving learning for all. New York, NY: Routledge.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10, 241-266.

Gardenswartz, L., & Rowe, A. (2003). Diverse teams at work: Capitalizing on the power of diversity. Alexandria, VA: Society for Human Resource Management.

Geertz, C. J. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York, NY: Basic.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2004). Bridging differences: effective intergroup communication (4th ed.). California, CA: Sage Publications.

Hall, E. T. (1977). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Hall, E. T. (1983). The dance of life: The other dimension of time. New York, NY: Doubleday and Company.

Hofstede G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Homan, A. C., Hollenbeck, J. R., Humphrey, S. E., Van Knippenberg, D., Ilgen, D. R. & Van Kleef, G. A. (2014). Facing differences with an open mind: Openness to experience, salience of intragroup differences and performance of diverse work groups. The Academy of Management Journal, 51(6), 1204-1222.

Jehn, K. A., Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. (1999). Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict and performance in workgroups. Administrative science quarterly, 44(4), 741-763.

Johnson, B. (1996). Polarity management: Identifying and managing unsolvable problems (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Human Resource Development.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F.P. (2009). Joining together (10th ed.). Columbus, OH: Pearson.

Kurtz, C. F., & Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM Systems Journal, 42(3), 462.

Li, A., Cropanzano, R., & Bagger, J. (2013). Justice climate and peer justice climate: A closer look. Small Group Research, 44(5), 563–592. doi:10.1177/1046496413498119

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups. Small group research, 27(2), 248-264.

Meeussen, L. Schaafsma, J., & Phalet, K. (2014). When values (do not) converge: Cultural diversity and value convergence in work groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 521-528.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (Eds.). (2002). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2011). Team‐based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 41-51. doi:10.1002/tl.467

Montgomery, C. (2009). A decade of internationalization: Has it influenced students view of cross-cultural group work at university? Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 256-270.

Moon, D. (2012). Multicultural teams: Where culture, leadership, decision making, and communication connect. William Carey International Development Journal, 1(3), 1-9.

Palsolé, S., & Awalt, C. (2008). Team-based learning in asynchronous online settings. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 116, 87-95. doi:10.1002/tl.336

Pieterse, A. N., Van Knippenberg, D., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2013) Cultural diversity and team performance: The role of team member goal orientation. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 782-804.

Royal Roads University. (2013). Learning and teaching model. Retrieved from http://www.royalroads.ca/about/learning-and-teaching-model

Salas, E., Sims, D. E., & Burke, C. S. (2005). Is there a “big five” in teamwork? Small Group Research, 36(5), 555–599. doi:10.1177/1046496405277134

Schein, E. H. (1999). What is process consultation? In Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schmidt, K. (2011). Cooperative work and coordinative practices: Contributions to the conceptual foundations of computer supported cooperative work (CSCW). New York, NY: Springer.

Stahl, G. K., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. (2010). Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of international business studies, 41(4), 690-709.

Staples, D. S., & Zhao, L. (2006). The effects of cultural diversity in virtual teams versus face-to-face teams. Group Decision and Negotiation, 15(4), 389-406.

Stearns, P. N. (2009). Educating global citizens in colleges and universities: Challenges and opportunities. New York, NY: Routledge.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Trompenaars. F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (2012). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business (3rd ed.). London, UK: Nicolas Brealey.

Van den Bossche, P., Gijselaers, W., Segers, M., Woltjer, G., & Kirschner, P. (2011). Team learning: building shared mental models. Instructional Science, 39(3), 283-301.

Wagner III, J. A., Humphrey, S. E.; Meyer, C. J., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2012). Individualism-collectivism and team member performance: Another look. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 946-963.

Waller, M. J., Conte, J. M., Gibson, C. B., & Carpenter, M. A. (2001). The effect of individual perceptions of deadlines on team performance. The Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 586-600.

Willey, K., & Gardner, A. (2009). Improving self- and peer assessment processes with technology. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 26(5), 379–399.

Zhang, Y., & Begley, T. M. (2011). Power distance and its moderating impact on empowerment and team participation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(17), 3601-3617.