12

Zhenyi Li

Associate Professor

School of Communication and Culture

Royal Roads University

Ining Chao

Instructional Designer

Center for Teaching and Educational Technologies

Royal Roads University

Abstract

We developed ICE (Interactive, Contextual, and Experiential) pedagogy for RRU MA-IIC program’s overseas residency by applying King and Baxter Magolda’s developmental framework for intercultural maturity (2005). Specific strategies to implement ICE pedagogy and lessons learned from our past experiences are discussed in this paper. The evolution of the ICE pedagogy exemplified RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model in action, particularly the principle of authentic and experiential learning. Royal Roads University (RRU) established the Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication (MA-IIC) program in 2005. Since its inception, RRU faculty have implemented a number of innovative pedagogy for best learning outcomes including intercultural competence development for the students. In this paper, we describe the evolution of the ICE pedagogy for the overseas residencies in MA-IIC as an example of RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model in action, particularly the principle of authentic and experiential learning.

MA-IIC Program and Overseas Residency

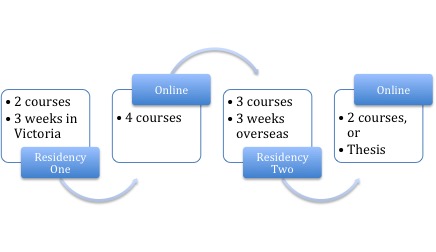

Like other programs at RRU, the MA-IIC employs an online distance and face-to-face residency blended model. The structure of the two-year 33-credit program starts with a three-week online pre-residency orientation related to the first two courses of the program. The first residency usually takes place in the autumn for two to three weeks, followed by a four-week online post-residency mainly designed for students to continue course discussion and assignment online submission. After that, students participate in four online courses for eight months before they return to a face-to-face residency for the second time. The second residency offers three courses with online pre- and post-residency components starting in September and ending in December. After the second residency, students are engaged in completing their theses and remaining courses online.

During the earlier years (2005-2007) of the program, each of the three-week residencies took place on the campus of RRU in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. However, both faculty and students saw the need to relocate the second residency abroad for two reasons. First, the overseas residency could set up a real intercultural and international learning environment that could benefit the students in the program focusing on their own intercultural competence development. Second, RRU has partners in China, India, and many other countries. Those partners could offer all necessary local supports, from faculty to classrooms, if RRU ran a residency on their campuses.

From 2008 to 2015, we ran the second residency for MA-IIC students in multiple cities in China and India and developed ICE pedagogy by applying the theories to overcome the barriers described below.

Developmental Framework for Intercultural Maturity

Intercultural competence development motivated us to move MA-IIC second residency abroad. We adopted King and Baxter Magolda’s developmental framework (2005) for intercultural maturity to set up our goal when designing MA-IIC overseas residency because we believed that all MA-IIC graduate should have achieved “genuine maturity.” Such “maturity,” as King and Baxter Magolda elaborated, refers to “not just knowing” cultural differences, but also being able “to apply their knowledge and skills in a variety of contexts” (p. 586).

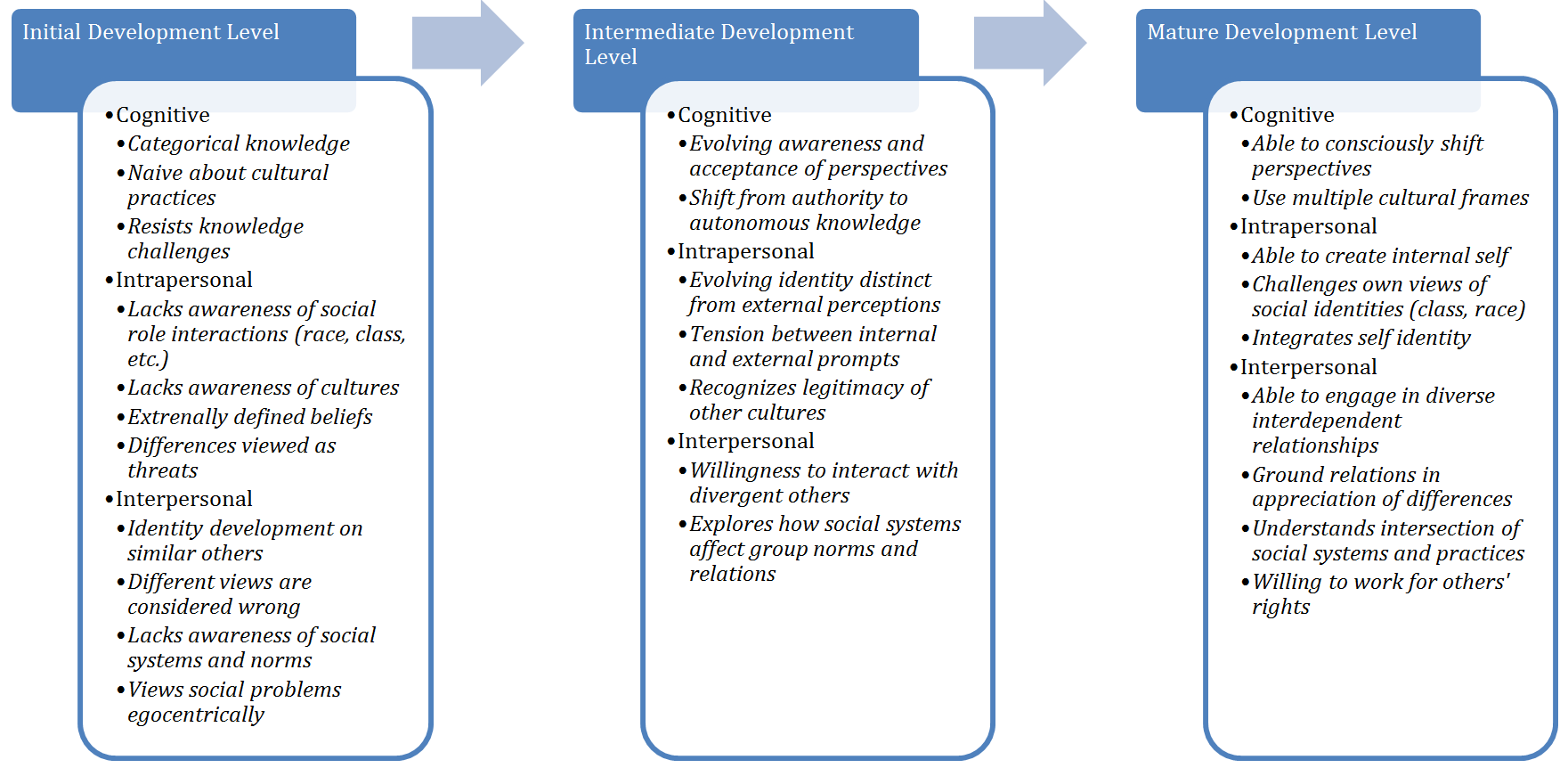

King and Baxter Magolda’s framework for intercultural maturity is multidimensional. First, it illustrates how one person could progress from an “initial” level of awareness, sensitivity, and ability to adapt to distinctions across cultures, through an “intermediate” level and towards a “mature” level. In addition, the framework includes the following three dimensions: how people see the world (cognitive), how they see themselves (intrapersonal), and how they relate to others (interpersonal). At the “mature” level, cognitively, a person is able to consciously shift perspectives and use multiple cultural frames. Intrapersonally, one is able to create internal self, challenge one’s own views of social identities, and integrate aspects of self into one’s identity. Interpersonally, a person is able to engage in diverse interdependent relationships, ground relations in appreciation of differences, understand intersection of social systems and practices, and is willing to work for others’ rights.

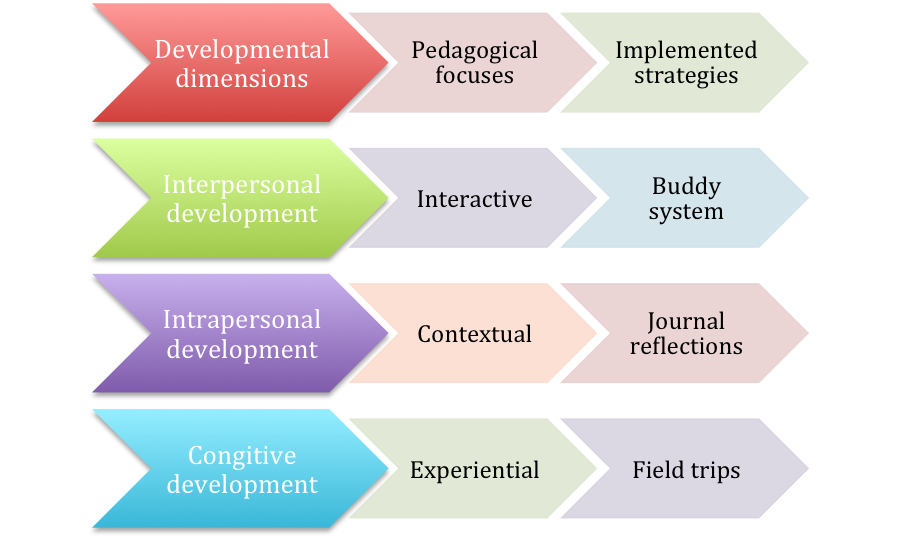

King and Baxter Magolda’s model of “intercultural maturity” helped us to choose pedagogical focuses and implement strategies in curriculum design and overseas residency planning. We set up a buddy system for our students to interact with local people for better interpersonal development. We assigned journal reflections for them to understand everything contextually for better intrapersonal development. We planned field trips for our students to expand their spectrum on cultural diversity from immersive experiences. Accordingly, we named our pedagogy ICE by emphasizing “interactive,” “contextual,” and “experiential” characteristics (see Figure 3).

The ICE Pedagogy

Interactive

Student interaction started before the face-to-face residency with various kinds of activities. Pre-departure preparation was vital to the success of the overseas residency. One of the initiatives in the design of the residency was to pair each of the Canadian students with a graduate student from a host university, two months before the residency. The Canadian students had plenty of questions related to their travel, the city they would stay for three weeks, and the local culture. It was also the first time for the Chinese graduate students to be partnered with students from other countries. They were curious about everything related to a Canadian graduate student’s life as well as ways to improve English proficiency. Both sides were highly motivated to exchange emails before they met each other. Interaction across cultures evolved naturally. The buddy relationship, in fact, lasted after the residency.

To improve interaction among the students, an afternoon debriefing after their “field study” was organised. The field study was a major component of the overseas residency. The students were required to get out of the classroom to observe and study what was happening in the “field”. For example, they visited a provincial prison, a software industry park, a kindergarten, an elementary school, a high school, and an insurance company. In the second week, the students were sent to different organizations and did their field studies by themselves. Those organizations included a hospital, a hotel, a travel agency, a bank, an IT training institute, an insurance agency, and a university college. After each field study, the students returned to the classroom in the late afternoon and debriefed what they had learned. The faculty-guided debriefing was a way to encourage interactive and collaborative learning. The students’ field studies, taking place in an ambiguous and uncertain environment, prompted the students to check with each other and look for help from co-learners. According to Gudykunst (2005), uncertainty is a cognitive phenomenon, while anxiety is an emotional one. Effective intercultural communication and learning must occur between the maximum and minimum thresholds for both uncertainty and anxiety. When above the maximum, we lose our confidence to predict others’ behaviour or to communicate with them. Below the minimum, we lose our motivation to interact with others. Therefore, in the overseas residency, the environment must provide sufficient uncertainty and anxiety to our learners and faculty must manage both within the proper threshold to ensure intercultural competence development. For example, the debriefing provided the students with a safe setting to share their frustrations, thoughts, and discoveries. The students were highly motivated and liked the collaborative and interactive learning in the debriefing. There was no intra-cohort segmentation in the overseas residency.

Contextual

Communication scholars believe each interpersonal or inter-organizational interaction takes place in certain contexts and so, understanding of communication has to be context-oriented. Context-based learning was emphasized and facilitated in the overseas residency through different means. One of the methods, specifically designed to assist self-reflection, is the journal entry activity. Related to that, in-class and online discussion also help the students to share their ideas, observations, and learning.

In the overseas residency, the students were asked to submit one journal entry every day during the first two weeks, which totalled 10 journals in 10 business days. Each journal entry was submitted by the student to the instructors at the very beginning of the day in a sealed envelope with the student’s name and date on it. The journal was mainly about what the student had seen, thought, and been told on the previous day. The students were asked to record details of the context from which they saw, thought, or were told something. The journals were returned to each student after the residency. The students were asked to open their own envelopes, and then read and compare their own journals from day one to day ten during the post-residency.

Many students found the journal entry helped them remember what happened in the residency. Furthermore, their own journals sometimes shocked them since the differences between any two days were remarkable. The students reported two significant developments in terms of: (a) their observation skills, and (b) their ways of thinking and reasoning. In other words, they utilized the opportunity of an overseas residency to develop their self-reflection skills and improve their awareness of their own culture. These are clear signs that the students became more sensitive in an intercultural setting (Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003, p. 440; Straffon, 2003, p. 499).

Understanding from context as a concept was taught in the students’ first year as an essential intercultural competence. It is not an easy idea to grasp until having practiced it in their everyday journal writing and in the post-residency summary of their journal entries. This was where the transformative learning happened. For example, one student had been thinking about “happiness” during the residency. She found that happiness, although it seems to be a universally desired objective of people worldwide, was understood, appreciated, expressed, and perceived differently in various cultures. After learning about the low salary of a Chinese foot massager, she first thought it was an unfair situation for such a skillful worker and that he must be unhappy. The student was asked to further investigate this issue by interviewing the worker and other people. What she learned was not simply that the worker was actually happy, but that her values and thoughts were based on her own culture. Overall, she learned more about herself and her own culture during the residency. That achieved the goal of this overseas residency.

Experiential

In the second year of their graduate studies, the students are expected to be able to apply theories and concepts they learned during their first year into real life. Experiential learning, hence, is an appropriate method to help them reach such a learning objective. According to Kolb, experience is the pivot that turns abstract concepts and theories into reflective observation and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984).

In particular, the supervised field study was designed to guide the students’ experiential learning. Supervision, mainly applied in the debriefing, was an essential piece in the field study. To some extent, the students’ learning and intercultural competence development would not take place without supervision. For example, significant changes took place in the second week. The students were assigned to “work” in a local organization for 20 hours. The 28 students were grouped into nine teams. Each team, with four students, was provided the name and address of the organization and the main contact person’s name and telephone number. The assignment for this “field study” was to write a report for Canadians about an intercultural communication aspect of doing business with the Chinese that the team believed to be essential. After a day spent in the Chinese organizations, nearly all the teams thought one day could be enough since there seemed to be nothing valuable for them to learn. Some complained that the host organization did not answer their questions. Some thought the host organization was not friendly. In the afternoon debriefing, the instructors asked if the students remembered key concepts in the field of intercultural studies. The students remembered, and as a consequence, their learning had evolved from “abstract” to “reflective observation” and “active experimentation” through “experience” (Kolb, 1984, p. 1). After that moment, students became more active in translating theories and concepts into practice. They were no longer armchair strategists. They had adjusted to the context by observing behaviours of the people in the host organization in order to modify their strategies to approach them, set up relationships with them, and learn from them. These were appropriate acculturation strategies (Berry, 2004, p.64) and the students became able to apply them in their real life learning.

Lessons Learned and Advice Offered

An intercultural environment is a pedagogical choice for educators to maximize opportunities for students to develop intercultural competence. For MA-IIC students with goals such as intercultural maturity, the intercultural environment should not be limited by face-to-face interaction or textbook-based knowledge learning. Since 2009, we have experimented with the overseas residency once a year for each cohort in their second year of study and gradually developed an online-offline blended “intercultural environment.” Most of our students appreciated such an intercultural environment and demonstrated significant cognitive and affective development in their own intercultural competence as a result of the overseas residencies. The design and delivery of overseas residency received a federal award from the Canadian Bureau of International Education (CBIE) for its innovativeness in 2011. The courses and locations of the overseas residency changed and evolved year by year in order to optimize learning opportunities. Nevertheless, one thing stays the same: the overseas residency is a purposeful intercultural environment designed for the students to achieve intercultural maturity.

Many factors account for the successes of ICE pedagogy during the overseas residency. Faculty and student engagement is obviously one of the most important factors. Support from both RRU and SDNU executives is another key factor. The increasing economic exchange and interdependency between Canada and China motivates the students to take the adventure. The successive Olympic Games hosted in Beijing and Vancouver, in 2008 and 2010 respectively, provided an imperative for the two sides to come together for better learning and understanding.

Organizing such an overseas residency required a considerable investment of human and financial resources. At least two full-time faculty and staff from Royal Roads University as well as six administrative staff and twelve faculty members from SDNU spent more than three months on this project. A web site with constantly updated residency information and answers to frequently asked questions was set up. Over 1,700 emails were exchanged between the program office and students regarding the residency. Also, three delegation visits between the two universities led by the university presidents took place before and during the residency. Lawyers were consulted to generate an agreement between the universities. Cancellation clauses and contingency plans to run the residency in Canada were prepared to avoid any possible interruption due to any possible natural disasters or international conflicts. The students were asked to purchase sufficient international travel and medical insurance as well as emergency contact information.

The success of the overseas residency was not achieved without efforts to overcome challenges that both faculty and students came across during the process. Student feedback and faculty reflection provided several recommendations. First and foremost, pedagogically, opportunities for interactive and collaborative learning should be provided, supported, and encouraged to overcome possible segmentation among the students in the process of developing their intercultural competence in an internalized setting. Internationalizing teaching and learning is about integration, not just the simple accumulation of diversity. The way to utilize the setting of internationalized learning should be carefully designed and guided by experienced faculty (Mullens & Cuper, 2012). A field study without supervision could turn into a study tour in an exotic culture without concrete skill development. In our case, the students were satisfied with their improvement in self-reflective abilities and understanding of their own culture. Intercultural maturity is a deliberate and intentional learning outcome at the centre of this overseas residency.

Experiential learning is one of the best ways for the students to translate and apply theories and concepts they learned from textbooks into real life issues. Real life experiences, when properly guided, are more effective than simulations and case studies in a classroom. Again, the key is to design experiential learning with the pedagogical goal in mind from the start. As mentioned earlier, detailed planning is necessary and one key element of the planning is managing students’ expectations prior to the departure. Furthermore, preparing the buddies from the host university is pivotal, as they also have expectations about their role and involvement in the program. All buddies are interested in experiential learning, not only because it does not exist in their curriculum, but also because they find they have learned the same, if not more than, as our students did. They must understand the goal is for them to share the knowledge about their own community and to explore cultural similarities and differences with the RRU students. It is not surprising to find this experiential learning benefits students from both sides because it is designed and delivered as true interactive intercultural learning.

Intercultural exploration does not stop at the superficial level of observing ethnic and national differences. When concluding each overseas residency, MA-IIC students presented their discoveries of differences and similarities across age, gender, experiences, education, profession, and many other aspects. The average age of our students was 35, while that of the SDNU students was 25. Many of our students have travelled and worked abroad while their buddies hardly had any international experiences. The majority of the RRU students are mid-career professionals, while the SDNU students had not finished their student life nor had much off-campus work experience. Sometimes these differences played a bigger role than ethnic diversity did. By arranging the overseas residency, our students learned first-hand that cultural differences were more profound—which is a mature cognitive development.

Last but not least, many MA-IIC students stay in touch with their buddies, even after many years. This cross-cultural long-distance friendship demonstrates how much Chinese people value long-term relationships (Hofstede, 2001). It is an effect beyond curriculum design, but within the realm of intercultural education. We are glad to see an overseas residency does not stop when it ends. We have the same hope that any intercultural collaboration lasts longer than planned.

Conclusion

Internationalizing higher education is not an issue that educators need to further agree on, but a challenge that both faculty and students still need to work out. The successful design and delivery of the Royal Roads intercultural overseas residency suggest that the ICE pedagogy can offer a model ensuring that students are acquiring the intercultural competence and maturity to become true global leaders.

References

Bennett, M. (1998). Intercultural communication: a current perspective. In M. Bennett (Ed.), Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Selected Readings (pp. 1-34). Yarmouth: Intercultural Publishing.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of stranger’s intercultural adjustment. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about Intercultural Communication (pp. 419-457). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hammer, M., Bennett, M., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: the intercultural development inventory, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 421-443.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

King, P., & Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity, Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 571-592.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Mullens, J. B., & Cuper, P. (2012). Fostering global citizenship through faculty-led international programs. Charlotte, N.C.: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Straffon, D. (2003) Assessing the intercultural sensitivity of high school students attending an international school. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 487-501.