Doug Hamilton

Professor

School of Education and Technology

Royal Roads University

Stephen L. Grundy

Vice-President Academic and Provost, Professor

School of Environment and Sustainability

Royal Roads University

George Veletsianos

Associate Professor

School of Education and Technology

Engaging Students in Life-Changing Learning: Royal Roads University’s Learning and Teaching Model in Practice presents examples illustrating how an institutional education model at Royal Roads University (RRU) is applied in practice. While numerous institutions across the globe are currently developing institutional models to improve student outcomes, experiences, and success, scholars have long lamented mismatches between theory and practice. In this book, we provide opportunities for faculty members and staff to describe their experiences with the Royal Roads University framework—the RRU Learning and Teaching Model–and illustrate how they use this model in their learning design and teaching. By engaging in this process, we hoped to learn from one another and become better practitioners, but also to enable peers at other institutions to explore how RRU practises education.

In this introduction, we provide a short background to RRU, a brief overview of the RRU Learning and Teaching Model, and an introduction to the chapters included in the book.

Royal Roads University: Our Unique Educational Mandate

When Royal Roads was created in 1995 as a public university, the government of British Columbia was responding to a need to serve those whose access to advanced education was limited within more traditional universities both in terms of labour market need and mode of education structure and delivery. The university was given a mandate from the government of British Columbia to respond to the emerging needs of a changing world and workforce. The enabling provincial legislation was very clear:

“The purposes of the university are

(a) to offer certificate, diploma and degree programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels in solely the applied and professional fields,

(b) to provide continuing education in response to the needs of the local community, and

(c) to maintain teaching excellence and research activities that support the university’s programs in response to the labour market needs of British Columbia. (Royal Roads University Act, 1996)”.

To achieve this mandate, programs were created which are interdisciplinary to maximize the learning experience for those students who seek to change and transform. The university now offers 50 interdisciplinary programs to over 5,000 students. Interdisciplinary research plays a significant role in most programs.

In order for students to stay in their home organizations and communities, and equally important, for those students to integrate their real world organizational and community experience into their academic programs of study, RRU developed a blended learning model. This model allows for short intensive residencies on campus combined with distance internet based courses. Although most other universities now offer alternative modes of delivery for some of their programing, when RRU was created, this was not the case. The blended model remains our primary mode of delivery across all of our schools. Digital delivery and technology enhanced learning are fundamental to our teaching.

The typical RRU student is 40 years old and is well established in his or her career. Through their learning and applied research from an interdisciplinary perspective, students enhance their leadership capacity, ability for complex problem solving and systemic thinking for the betterment of their communities and organizations.

The expertise of industry, the public sector, and institutional partners are incorporated into program development and instructional delivery to ensure the highest possible level of program relevance and quality. As such, RRU has developed its unique niche in providing applied and professional learning programs adapted to a changing workplace.

Complementary to its teaching programs, RRU has developed a research program that is almost exclusively applied, responding to the economic, social, and environmental concerns of British Columbians and beyond.

Over the last 20 years, we have developed a national and international reputation for delivering high quality programs. National and international studies have confirmed this reputation. For instance, Royal Roads University has consistently ranked very high on the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) for active and collaborative learning and academic challenge (NSSE, 2012; Macleans, 2012).

Overview of the Learning and Teaching Model at Royal Roads University

At its most fundamental level, an institutional framework for learning and teaching describes the current, robust, and agreed-upon educational characteristics that help define the unique identity of the university or college, especially pertaining to its core educative mission. It provides a means of connecting the university’s mission and values to the learning and teaching practices that support them. The introductory chapter will describe in more detail the rationale for developing institutional frameworks using RRU as a case study. The RRU Learning and Teaching Model was intended to describe the distinctive characteristics of the current university-wide approach to learning and teaching (Royal Roads University, 2013). It included an inductively generated description of the educational principles, characteristics, or elements that guide learning and teaching combined with a summary of the relevant and current research literature on learning, teaching, and andragogical innovation.

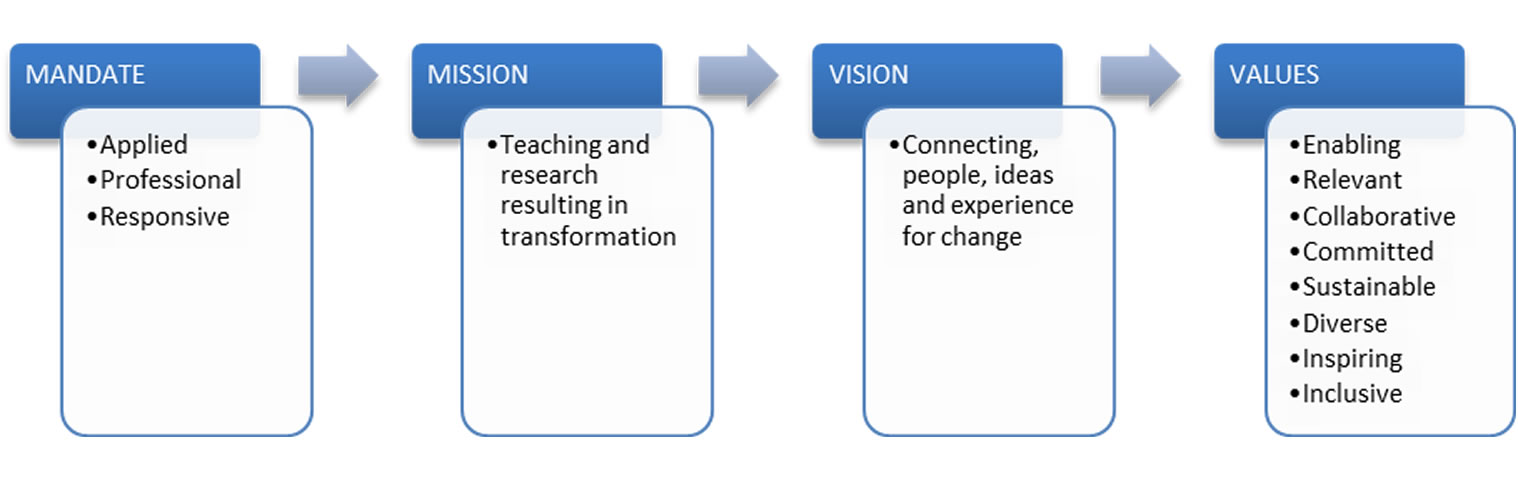

The description of the model begins with the university’s mission to immerse students in a learning context that facilitates personal and professional transformation and allows them to succeed in a global workplace. As illustrated in Figure 1, a set of values emerged from this context that guided the development of our learning and teaching framework.

Foundational Frameworks

At the heart of the student experience is a focus on meaningful, relevant, and lifelong learning that permeates all educational offerings at RRU, including degree, non-degree, and continuing education programs. UNESCO’s Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century (Delors, 1996) and subsequent work by UNESCO’S Education for Sustainable Development Initiative (2012) presented a conceptual framework for ongoing, lifelong learning that applies very well to the RRU context[1]. This model organizes learning into the following five pillars:

1. Learning to Know – the development of skills and knowledge needed to function in this world e.g. formal acquisition of literacy, numeracy, critical thinking and general knowledge (the mastery of learning tools).

2. Learning to Do – the acquisition of applied skills linked to professional success.

3. Learning to Live Together – the development of social skills and values, such as respect and concern for others, of social and inter-personal skills, and the appreciation of cultural diversity. These are fundamental building blocks for social cohesion, as they foster mutual trust and support and strengthen our communities and society as a whole.

4. Learning to Be – the learning that contributes to a person’s mind, body, and spirit. Skills include creativity and personal discovery, acquired through reading, the Internet, and activities such as sports and arts.

5. Learning to Transform Oneself and Society – when individuals and groups gain knowledge, develop skills, and acquire new values as a result of learning, they are equipped with tools and mindsets for creating lasting change in organizations, communities, and societies.

These five pillars are linked together by a social constructivist approach to individual learning and a social constructionist approach to the development of learning communities that significantly influences how students learn and how faculty and staff support their learning at RRU. There is general agreement that a social constructivist orientation includes the following key elements (Mayes & de Freitas, 2004; Beetham & Sharpe, 2007):

- self-responsibility for learning that enables students to actively construct their own understanding of concepts;

- complex problems to support a discovery-oriented approach to learning;

- open-ended activities and challenges to encourage experimentation and risk-taking;

- collaborative inquiry with peers and faculty members to help learn faster or deeper than when solely engaged in individual activities;

- shared ownership of the learning process to facilitate a common understanding and shared meaning of the tasks and experiences involved in learning;

- discussion and reflection that draws on existing concepts, contexts, and skills; and

- timely and effective feedback to guide correction and improvement in concept and skill attainment.

The social constructivist/constructionist orientation is a foundation for both a set of principles that guide the learning and teaching process, i.e. the RRU Teaching Philosophy, and a constellation of practices, i.e. Core Elements of our Learning and Teaching Model.

Taken together in a summary fashion, Table 1 illustrates that at RRU, we understand learning as a socially constructed activity and we conceptualize lifelong learning as a process of social and personal discovery beyond the acquisition of knowledge.

| Social Constructivist Framework | UNESCO Framework |

| Self Responsibility | Learning to Know |

| Complex Problems | Learning to Do |

| Collaborative Inquiry | Learning to Live Together |

| Open Ended Learning Activities | Learning to Be |

| Discussion and Reflection | Learning to Transform Oneself and Society |

| People Learn in a Diversity of Ways | Learning to Know |

RRU Teaching Philosophy

The implementation of curriculum development and teaching strategies that reinforce the social constructivist view of learning at RRU is supported by a robust teaching philosophy collaboratively developed by faculty and staff. This philosophy indicates that, at Royal Roads University, faculty members and academic staff:

- share a passion for learning and teaching;

- value students as individuals who bring expertise and life experience to their education, and support them as they construct knowledge in a personally relevant way and enhance their lifelong learning skills;

- focus on applied and professional learning and integrate research into the curriculum;

- are experts in many substantive areas of knowledge and take steps to share this knowledge in ways that do not interfere with the adult student responsibility to learn and reflect for themselves;

- are knowledgeable in their areas of expertise and in current adult learning theory;

- know how to use appropriate learning technologies for the desired learning objectives;

- believe that teaching is a critically reflective practice;

- foster learning environments that are respectful, welcoming, and inclusive;

- facilitate learning experiences that are authentic, challenging, collaborative, and engaging;

- model and encourage academic integrity;

- aspire, as lifelong learners, to create experiences where new learning changes all members of the learning community and where students contribute meaningfully to the learning of others; and

- actively participate in the University’s global learning community.

This teaching philosophy is complemented by the ways in which our programs are designed, our courses are developed and taught, and our students are supported.

Core Elements of our Learning and Teaching Model

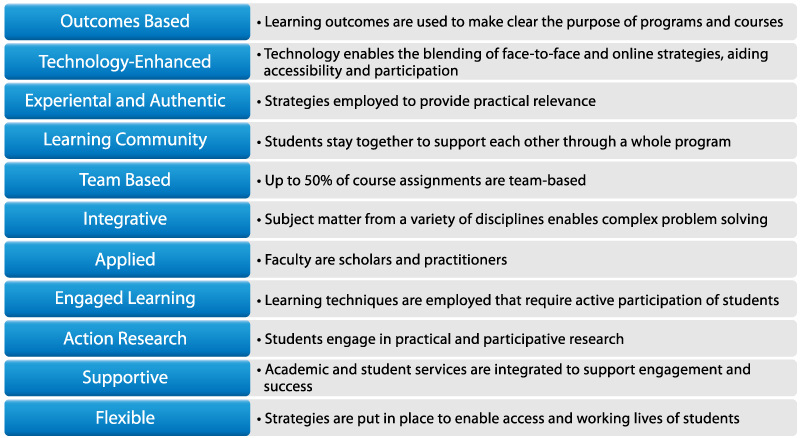

Despite the different contexts and mandates, most programs at RRU share a number of fundamental curriculum design elements, learning processes, and support services that work together to support authentic, relevant, and meaningful student learning. These curriculum design elements and learning processes, summarized in Figure 2 and Table 2, are described in more detail below.

| Component or Strategy | Advantages |

|

1. Outcomes-Based – all curriculum is developed and delivered using program-wide learning outcomes that are created in consultation with expert advisory councils. |

• Clarifies program focus • Helps students connect program to workplace • Provides a focus for assessment/evaluation • Helps employers understand program benefits |

|

2. Enhancing Learning through Technology – most programs, and sometimes even individual courses, feature a blend of short-term, on-campus residencies, and online learning courses that are made possible by the use of web technologies. |

• Enhances access and relevance—students can continue to work and engage in a reflective cycle involving reading or other learning activities, applying new skills and knowledge in the workplace, and reflecting on what worked, while engaging with others in online dialogue throughout the learning cycle • Provides complementary social learning processes: online engagement enhances deep-level thinking and the exchange of perspectives; understanding how others interpret or experience a phenomenon gives students a broader understanding about possible learning strategies • Residencies help students make personal connections to faculty and other students |

|

3. Experiential, Authentic Learning Strategies – problem-based learning, project-based learning, service learning, action learning, action research, etc. |

• Provides a more integrative experience • Enhances practical relevance • Deepens learning by focusing on systemic understanding and distinctions between simple, complicated, and complex problems, issues, and challenges • Provides students with a more realistic understanding of their profession |

|

4. Learning Communities – groups of 20-50 students work together as a cohort for the duration of the program, frequently forming a lifelong professional community. |

• Helps students experience a strong sense of connectedness, collegial support, and shared experiences • Increases access to professional knowledge of colleagues and peers • Exposes students to a diversity of views, experiences, perspectives, and scholarship • Creates a broad base of readily available learning resources |

|

5. Team-Based Learning – up to 50% of course assignments may involve group projects or team-based work. |

• Enhances skills related to collaboration, team facilitation, project management, conflict management, etc. • Makes large assignments more manageable and realistic • Provides opportunities for more complex learning |

|

6. Supporting Integrative Learning –programs and courses bring together subject matter from a variety of disciplines and feature teaching strategies that help students make connections across subjects and between thinking and doing, e.g. capstone courses, team-teaching, integrated course delivery, integrative assignments. |

• Increases relevance and authenticity to workplace • Provides tools, resources, and approaches suitable to solving complex problems and managing emerging issues • Makes connections across courses • Promotes relevance and meaningfulness • Helps students apply higher-order thinking skills such as analysis and synthesis • Promotes praxis—strengthens links between theory and practice |

|

7. Faculty with Professional Experience –faculty collectively possess strong academic credentials and significant experience in the application of the subject matter to professional contexts. |

• Enhances relevance for students • Helps faculty members mentor and guide students • Fosters links between academic and professional perspectives • Requires scholar-practitioner faculty members who are able to bridge the worlds of scholarship and applied practice with maturity and the confidence to play a supporting role to student learning |

|

8. Teaching as an Active Process of Facilitating Learning – faculty use a variety of strategies to engage students and support/guide the learning process. |

• Helps students understand and integrate the ideas of a given course with their personal experiences to create personally relevant and actionable knowledge • Increases students’ personal responsibility • Acknowledges student experience and expertise as relevant and critical sources of knowledge for others • Enhances teaching quality and relevance |

|

9. Action-Oriented Research as a Process of Inquiry—students develop meaningful research questions and engage in worthwhile investigations to solve real organizational, community-based, or societal problems. |

• Links systematic inquiry to workplace issues and problems • Provides a professional context for the integration and application of concepts and skills learned in other components of the program • Create opportunities for positive and meaningful change to occur |

|

10. A Whole Community of Support – RRU staff from many different services work together to deliver timely and integrated student support. |

• Helps connect many different RRU services to students, e.g. program support, student services, library, instruction design, continuing education, media, information technology, etc. • Provides a seamless suite of services to students |

|

11. Flexible Access–a variety of structures have been implemented, e.g. flexible admissions, block transfer agreements, dual degree partnerships, etc. to support a smooth entry of students into RRU programs. |

• Recognizes the importance and value of relevant workplace and life experience • Acknowledges the value of both formal and informal learning • Provides multiple pathways of entry into RRU programs |

The model was intended to be evolving and generative. The goal in developing the model was not to advocate for one ‘best way’ to teach, but to integrate common design elements in RRU programs. None of these methods, on their own, are effective in supporting high-quality student learning. We contend that it is how these elements work together in the service of authentic and relevant learning that create engaging and relevant experiences for today’s and tomorrow’s students at RRU.

Key Themes within the Book

The book spans and crosses disciplines and ways of thinking. Some of the chapters are empirical, some are reflective, but all aim to contribute significant insight into how staff and academics in the institution perceive their teaching and scholarship, and how they come to practice the RRU Learning and Teaching Model. The introductory chapter by Hamilton, Márquez, and Agger-Gupta investigates the emergence of institutional educational frameworks and describes the RRU Learning and Teaching Model. To provide a compass to readers, the rest of the book is divided into four thematic sections.

In the first section, authors are concerned with learner experiences and outcomes:

- Walinga and Harris (chapter 1) examine students’ transformative learning experiences and report how learners came to question their assumptions and gain new consciousness in their learning.

- Wilson-Mah and Thomlinson (chapter 2) explore tourism/hospitality students’ and internship employers’ perceptions of internship programs. They report positive experiences with internship programs, note that such experiences allow learners to apply theory to practice, and present recommendations for improving internship programs.

- Wesolowska and Agger-Gupta (chapter 3) report one student’s experience in creating a community engagement process to define sustainable downtown revitalization. This chapter provides an insider look into the authentic and experiential activities that the RRU Learning and Teaching Model aims to engender.

In the second section of the book, authors report investigations of faculty perspectives with one or more aspects of aspect of the RRU Learning and Teaching Model.

- Hamilton and Childs (chapter 4) investigate faculty members’ perspectives on how the key pillars of the Learning and Teaching framework were incorporated into the design and delivery of the learning program.

- Students in traditional one-to-one capstone projects may experience social and academic isolation. Rowe, Harris, Graf, and Rogers (chapter 5) report that group supervision for students completing capstone projects may address such problems and investigate faculty members’ benefits and challenges in using Moodle for group supervision.

In the third section, authors describe various learning designs and pedagogies enacted and developed under the auspices of the RRU Learning and Teaching Model.

- Wood, Márquez, and Hamilton (chapter 6) present Applied Business Challenges, which are problem-based learning experiences aiming to immerse students in analyzing and resolving business challenges via internal case competitions, international case competitions, and live-case consulting projects.

- Page, Etmanski, and Agger-Gupta (chapter 7) identify and explore the intentional design that serves to build multiple opportunities for learner belonging and longstanding relationships.

- Malisius (chapter 8) argues for providing students with diverse learning opportunities and investigates how video assignments may potentially be used in blended settings.

- Slick (chapter 9) describes how the author used learning theory to design a case study. This article draws widely from the literature as well as from the author’s personal experience implementing the case over a five-year period.

- Chao and Pardy (chapter 10) argue for the adoption of an intercultural mindset supported by responsive team composition, intercultural training, teamwork-appropriate assignment design, and multi-dimensional assessment of teamwork.

- Agger-Gupta and Perodeau (chapter 11) present appreciative inquiry as an approach that supports the enactment of RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model.

- Li and Chao (chapter 12) describe a form of pedagogy they denote as Interactive, Contextual, and Experiential (ICE), and present their experiences implementing this approach.

In the fourth and final section of the book, authors examine macro level topics of interest to the institution.

- Grundy (chapter 13) examines the effect of flexible admission practices on academic performance. Results show that flexible admission students do equally well to those admitted on the basis of previous academic credentials.

- Belcher (chapter 14) investigates RRU’s unique research model and reviews the research completed by RRU graduate students. Through this investigation, he examines how to improve student research and its design, evaluation, and learning.

- Finally, Young, Malisius, and Dueck (chapter 15) explore the role of the Curriculum Committee at RRU—a committee that evaluates and provides feedback on course proposals.

References

Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (2007). Appendix 1: How people learn and the implications for design. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: Designing and delivering e-learning (pp. 221-223). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cox, R., Huber, M.T., & Hutchings, P. (2004). Survey of CASTL scholars. Stanford, CA: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0010/001095/109590eo.pdf.

Macleans Magazine. (2012). How students rate their experiences at 62 Canadian schools: Results from the National Survey of Student Engagement. Retrieved from http://oncampus.macleans.ca/education/2012/02/08/how-students-rate-professors-at-62-canadian-schools/.

Mayes, T., & de Freitas, S. (2004). Review of e-learning theories, frameworks and models: JISC e-learning models study report. Retrieved from http://www.jisc.ac.uk/elp_outcomes.html.

National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). (2012). What is NSSE? Retrieved from http://nsse.iub.edu/html/about.cfm.

Royal Roads University. (2013). Learning and teaching model. Retrieved from http://www.royalroads.ca/about/learning-and-teaching-model.

Royal Roads University Act. (1996). Queens Printer, [RSBC 1996], Chapter 409.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2012). Education for sustainable development. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-sustainable-development/.

Weimer, M. (2006). Enhancing scholarly work on teaching and learning: Professional literature that makes a difference. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- This conceptual framework also serves as the basis for the development of the Canadian Council on Learning’s Composite Learning Index (CLI). ↵