1

Jennifer Walinga

Director

School of Communication and Culture

Royal Roads University

Brigitte Harris

Director

School of Leadership Studies

Royal Roads University

Abstract

This narrative inquiry examines students’ stories of transformative learning. The paper describes the constructivist, social constructionist, and transdisciplinary theoretical roots of Royal Roads University’s Learning and Teaching Model. It also reviews the literature on transformative learning, stages of change, change readiness, and transformative change facilitation models. Five hundred and sixty students in the Master of Arts in Educational Leadership and Management (MAELM), Master of Arts in Professional Communication (MAPC), Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication (MAIIC), and Master of Arts in Leadership (MAL) programs were invited to participate in an anonymous survey to elicit their perceptions and stories. We received 94 responses, which were analysed for themes and insights into the meaning-making processes. Eight stages of transformative learning were identified: (1) a disorienting dilemma, (2) a threat or challenge which presented an opportunity to reflect, (3) a conscious choice to reflect and problem solve, (4) questioning of assumptions, (5) releasing old ways of knowing, (6) reaching a new level of consciousness or insight, (7) feelings of satisfaction and freedom and/or sadness, and (8) enduring change. Students experienced disequilibrium as a result of struggling to make meaning of an unfamiliar learning environment that deliberately fosters questioning of assumptions. This struggle triggered deep learning and, ultimately, transformation, as predicted in the literature. For our participants, however, the reward was in the new consciousness. This study both affirms the utility of transformative learning and helps us to better understand the student experience. This increased understanding will allow us to better support students on their learning journey.

*

Introduction and Overview

Royal Roads University (RRU)’s Learning and Teaching Model (LTM) describes educational practices and program design features that promote transformational learning. While institutions or programs may support some elements of the Model, the process by which they were identified and drafted into a statement that both espouses and guides the University’s teaching and learning approach is, to our knowledge, unique in a higher education setting. A dean and two faculty members set out to capture what made RRU’s learning and teaching approach distinctive, and engaged in successive discussions with faculty and staff members to deepen their understanding and ensure they captured learning practices across the University. The resulting document, Royal Roads University Learning and Teaching Model (Hamilton, Márquez, & Agger-Gupta, 2013), was vetted by faculty again before it was finalized. The resulting document describes a unique and integrated educational approach as well as associated values. This educational approach often differs from what our students have experienced in a previous education context.

As faculty members, we have observed that new students may experience a learning curve associated with the University’s instructional practices and learning environment. While many students told us that they were drawn to the philosophy of the University, they soon realized that their previous educational experiences and the way they learned to learn did not prepare them for the learning and teaching expectations in many of the Royal Roads University programs. For instance, how does one co-create knowledge when he or she has only experienced learning as transmitted from a teacher-expert? How does one learn with student-peers in community when one’s previous experience of learning was a process between teacher and student? Or how does one translate the traditional conception of academic rigour into an applied learning and research context? This paper explores RRU students’ experiences of learning to learn at RRU. We will identify ways that students reconcile tensions, conflicting beliefs, assumptions, and values in order to more fully and effectively experience and benefit from RRU’s transformational learning approach.

We wondered what students’ stories of transformative learning could tell us about their transformational process. The research questions that guided us are as follows:

- How does the RRU Teaching and Learning model influence the learning environment and experience of students?

- In what ways do students experience and resolve conflicts between standard and transformative learning models?

This paper describes theoretical foundations underlying RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model and reviews the literature on transformational learning, stages of change, change readiness, and transformative change facilitation models. We then present our research methodology and methods, the findings of our study, and our recommendations for practice and further research.

Principles and Practices of RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model

Fullan and Scott (2009) call on universities to create practical and engaging educational experiences that prepare students to become leaders capable of working with others to solve the complex and divisive problems that confront the world in the 21st century (p. 42). Royal Roads University explicitly states its role in educating such leaders through “immersing students in a learning context that that facilitates and promotes personal and professional transformation and allows them to succeed in a global context” (Hamilton, Márquez & Agger-Gupta, 2013, p. 2, our emphasis). RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model describes guiding principles and practices that promote transformational learning and teaching practices. It sets out 11 educational practices that, together, promote the development of the type of leaders the world needs:

- Students are active and engaged in their learning, and faculty provide them with learning experiences, and facilitate and coach them.

- Experiential and authentic activities and assessment allow students to reflect on and apply their learning to their own practice and the real world.

- Outcomes-based assessment guides learning by stating clearly what a student should know, be able to do, or value through an assignment, a course, or a program.

- Students engage in practical and participative research (often action research) to address real world issues.

- Integrated curriculum provides opportunities for students to apply knowledge, approaches, and perspectives to solving real world problems.

- Faculty are scholars and practitioners, bringing their real world experience to their teaching and ensuring that what students learn can be applied in their practice.

- The best of blended (face-to-face and online) teaching strategies facilitate student participation and accessibility.

- Students enter and complete their program in the same cohort, developing relationships that support, enrich, and enhance their learning.

- Students explicitly learn to work effectively in teams through numerous team activities and assignments.

- Integrated academic and student services support engagement and success.

- Flexible program designs ensure they are accessible and fit into the lives of working students.

RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model explicitly embraces constructivist and social constructionist principles[1]. Constructivism emerged from John Dewey’s (1938) theory of experience and education. He saw learning as an individual’s active inquiry process in interaction with the world, in contrast to the rote learning approach of “traditional education”. Key here is that adult learners are active agents and participants in their learning rather than empty vessels and passive recipients of knowledge from others. Further, an individual’s learning does not occur in isolation; rather, it becomes part of an “experiential continuum,” (p. 33) meaning that learning is influenced by what is already known and what is known influences subsequent learning. Social constructivism adds that an individual’s knowledge construction takes place within a social context, which influences the learning process and “socially agreeable interpretations” (Adams, 2006, p. 246). Shaped by influential theorists like Piaget, Vygotsky, Freire, and Bruner[2], constructivist learning theory asserts that “genuine learning occurs when students are actively engaged in the process of discussing ideas, interpreting meaning, and constructing knowledge” (Gordon, 2009). Thus, while faculty still need content expertise (Gordon, 2009), they must also know how to guide and coach learners and create engaging learning experiences. Their facilitation entails a solid grounding in adult learning principles that promote self-direction and the application of theory to practice.

While social constructivism understands learning as something that occurs as individuals interact with other individuals and the world, social constructionism posits that “we construct multiple and emerging ‘realities’ and selves with others through our dialogue” (Cunliffe, 2008, p. 135). “[S]ee[ing] ourselves as collaborators, co-constructing our identities and behaviour in a dynamic dance with discourses” (Alford, 2012, p. 299) can lead to greater insight, particularly about learning. The cohort model (#8 of the Learning and Teaching Model) creates a tightly knit learning community, providing an environment which supports learners in co-creation of knowledge and identity through dialogue. These relationships, culture, and common language bind learners to others in their program at RRU (Harris & Agger-Gupta, 2014).

The Learning and Teaching model also aligns with the aims, approaches and values of transdisciplinary teaching, learning, and research. McGregor (2014) defines transdisciplinarity as “iteratively crossing back and forth and among and beyond disciplinary and sectorial boundaries to solve the complex, wicked problems of humanity” (p. 161). It has three broad characteristics. First, it aims to solve complex and multidimensional real world problems that cannot be solved within “the boundaries of a single discipline” (Wickson, Carew, & Russell, 2006, p. 1048). Second, transdisciplinary (as opposed to interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary) research moves beyond disciplinary boundaries, which results in the “construction of unique methodologies tailored to the problem and context” (Wickson et al., 2006, p. 1050). Third, transdisciplinary researchers engage in collaborative knowledge production between researchers and stakeholders (Wickson et al., 2006; Carew & Wickson, 2010). The Learning and Teaching Model elements of action research focus (#4), integrated curriculum (#5), and applied learning (#6) bring transdisciplinary knowledge production approaches to life as a pedagogic strategy. Transdisciplinarity, according to Nicolescu (n.d.) “is a way of self-transformation oriented towards knowledge of the self, the unity of knowledge, and the creation of a new art of living in society” (p. 3). He goes on to observe that “transdisciplinary evolution of education” is required to address the urgent and vexing problems of the world. Likewise, transformative learning is grounded in and dependent upon the capacity to think across disciplines. It is this expansive, inclusive thinking that allows us to tolerate ambiguity, sit with a dilemma, and in turn navigate complex challenges to one’s existing paradigm, beliefs, or assumptions through the releasing and embracing of ways of knowing.

This transdisciplinary evolution of education is apparent in UNESCO’s (2013) five educational pillars—learning to know, do, live together, be, and transform oneself and society—which provide a foundation for RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model and are grounded within the work of Jacques Delors (1996) as well as the discussion of his work by Tawil and colleagues (2012; 2013). Originally conceived as a framework for transformational environmental education, it addresses the whole-person, multi-dimensional, and transdisciplinary learning needed to resolve the urgent, difficult, and complex problems confronting people, communities, societies, and the world. Learning, according to the UNESCO framework, extends beyond knowledge acquisition and skills application to working productively and inclusively with others, nurturing and providing individual growth of the whole person, and working for the common good. The UNESCO model explicitly links transdisciplinarity, personal transformation, and social transformation. And while our students tell us of their personal transformation through testimonials and evaluative comments, many alumni have told us of how that personal transformation, in turn, enabled them to create positive change in the lives of others, whether in their families, workplaces or communities.

Theoretical Framework for Transformational Learning

Definitions of Personal Transformation

Transformation is defined as a metamorphosis, conversion, or complete change in form, shape, or appearance, usually into something with an improved appearance or usefulness (Oxford English Dictionary, 2006). The concept of personal transformation has multi-disciplinary relevance. Specifically, the topic has been explored in relation to education, behavioural science, health, cognition, and athletics. Throughout the literature, personal transformation is described using several different terms reflecting diverse contexts. Terms for personal transformation include individuation (Jung, 1921), critical transition (Skar, 2004), transformative world view (Scheiren, 2004; Taber, 1983, Smith, 1984; Watson, 1989), transformative logic (Loder 1981), perspective transformation (Carpenter, 1994; Mezirow, 1978, 1991), and transformative learning (Carpenter, 1994; Mezirow, 1995, 1997, 2000). Along with the more formal definition of personal transformation as a “forming over or restructuring,” Wade (1998) derives the following definition from her literature review: “a dynamic, uniquely individualized process of expanding consciousness whereby individuals become critically aware of old and new self-views and choose to integrate these views into a new self-definition” (p. 716). Wade explains that while “the thrill and focus of transformation may not be sustained indefinitely, the individual continues to live by what has been seen” (p. 717). Royal Roads University strives to facilitate transformational learning in its students as part of a larger teaching and learning model. By its nature, the approach can inspire tension, dissonance, and resistance. This study aims to understand how students experienced the RRU model and how they approach resulting tensions.

Personal transformation finds its roots in the realms of educational, cognitive, and behavioural psychology, including such theorists as: John Dewey (1859-1952) and his theory of “experiential education,” Carl Jung (1875-1961) and his theory of “individuation,” Kurt Lewin (1890-1947) and his “field theory” and “dynamic theory of personality,” Jean Piaget (1895-1980) and his theory of “accommodative learning,” Lev Vgotsky (1896-1934) and his “social development theory,” Paulo Freire (1921-1997) and his theory of “liberation through education,” Ivan Illich (1926-2002) and his theories of “deschooling” and “raising consciousness,” and Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996) and his concept of “paradigm shift.” While these historical theories derive from diverse disciplinary perspectives, they share several common transformative principles: i) transactional development as the individual interacts with his environment, ii) a disposition for change or critical life transition, iii) a point of “bifurcation” and process of equilibration, and iv) a final reorganization or “transformation” of the individual’s world view and consequent behaviour.

Modern theorists and researchers have attempted to capture the transformative process by exploring emergent patterns, categorizing the phases or stages of transformation, and identifying means and conditions for effectively facilitating the transformative process. As well, recent researchers have shown that individuals who experience personal transformation believe they have more freedom, more creativity, and greater capacity for stress tolerance (Gould, 1978; Loder, 1981; Wildermeersch & Leirman, 1988).

Modern theories of personal transformation stem from work in the area of education, health, theology, and psychology. Examples include: Jack Mezirow’s “perspective transformation” or “transformative learning” (1978, 1991, 1995, 1997), Robert Havighurst’s theory of “mobilized energy” and change (1972, 1979), Robert Kegan’s theory of “constructive development” (1982), James Fowler’s “faith development theory” (1981), James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente’s “transtheoretical model of change” (1982), Robert Boyd’s theory of “discernment” (1989), Kathleen King’s “Learning Opportunities Model” (2002), Edward Taylor’s exploration of the “neurobiological role in transformative change” (2001), Richard Boyatzis’ “intentional change theory” (2002), Roy Baumeister’s “crystallization of discontent” (1994), and Jack Bauer’s “crystallization of desire” (2005). From each of the theories arises the idea that personal transformation is an internal creative problem-solving process occurring at the level of the unconscious but sparked by an interactive dissonance between environment and individual affective/cognitive processes. In reviewing the literature on personal transformation, the common principles of the transformative process appear to follow a set of stages (Table 1). Critical to the transformative learning process appears the confrontation of a disorienting dilemma or feeling of being “stuck”. It is the experience of failing or being stuck no matter which path you choose that prompts a willingness to pause, look elsewhere, and reflect. This theoretical and conceptual model guided our analysis by providing categories by which to code and theme our data.

|

a) A disorienting dilemma or problem (Ferguson, 1980; Skar, 2004; Loder, 1981; Busick, 1989; Mezirow, 1991), causing b) a threatening and challenging opportunity for reflection, problem solving, and expansion of consciousness (Bailey, 1996, Duff 1989, Ferguson 1980, Loder, 1981; Mezirow, 1991; Neuman, 1996; Pierce, 1986; Watson, 1989), at which point the individual must c) make a deliberate choice to confront the conflict or dilemma (Busick, 1989; Newman, 1994; Ferguson, 1980; Smith, 1984; Wildemeersch & Lierman, 1988) by d) questioning assumptions (Hagberg, 2002; Kegan, 2000; Mezirow, 1991; Schein, 1999; Walker, 2000), e) releasing old ways of knowing, becoming receptive to new ways of viewing the self, and reinterpreting experiences in a new context (Loder, 1981; Mezirow, 1991). This results in f) a new level of consciousness or insight which unites the mind and heart to form a new self-definition (Ferguson, 1980; Mezirow, 1991) and express a more inclusive, differentiated, permeable, and integrated meaning perspective (Dirkx, 2000; Loder, 1981; Busick, 1989; Mezirow, 1991). Transformation is followed by g) feelings of excitement, satisfaction, and freedom as well as sadness associated with loss of the old self (Dirkx, 2000; Ferguson, 1980; Busick, 1989; Duff, 1989; Newman, 1994). Finally, transformation is h) enduring change in attitude and behaviour. Once transformation has occurred, the individual never returns to the old perspective (Ferguson, 1980; Duff, 1989; Mezirow, 1991). |

Methods for Studying Personal Transformation

This study explores the interactions between internal and external factors on the student experience of the RRU transformational learning model. In the wide variety of studies performed and theories developed in the area of personal transformation, a consistent complaint among researchers is the intangible nature of the transformative process. To empirically test theorems related to the concept, several measurement instruments may be needed, placing artificial limits on the data elements. Qualitative research may be most effective at revealing the unfolding of patterns associated with the transformation process. Wade (1998), in her review of studies in personal transformation in the health, behavioural, and educational sciences, found only one empirical study performed in the area of personal transformation (Williams, 1987), and even then, found that the qualitative measures were more reliable and telling than the quantitative instruments involved. Williams explored the relationship between perspective transformation and changes in abusive spousal behaviours following a twelve-week educational program. Five self-report instruments were administered to measure outcomes related to perspective transformation, including: Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale, Conflict Tactics Scale, Rotter’s Locus of Control Scale, the Index of Role Preferences, and an Index of Spouse Abuse. Intake and exit interviews were also used and rated by a therapist and three researchers using Mezirow’s ten phases of perspective transformation. Williams found that the qualitative perspective transformation ratings were of greater value than the measurement tools in analysing the process of personal transformation. This study involves a qualitative content analysis of student reflections and discussions of the RRU learning and teaching model in order to form a clearer picture of the transformational learning experience.

Facilitating Transformational Learning

Many studies explore methods or conditions for facilitating the transformative process. For example, Taylor (1998) identifies 11 dissertations exploring transformative learning alone. There appears to be no “best practice” for fostering personal transformation (Taylor, 1998). Taylor complains of a lack of thorough literature review in the area, criticizing transformative learning theory in particular for “lack of coordinated efforts” to build upon existing studies. He specifically calls for a process to facilitate personal transformation that is not limited by “ideal conditions” but is adaptable to a variety of individual situations (p. 61). In his paper exploring the mechanisms of critical transitions, Kuhn (1972) complains that “it is the requirement that mental operations be applied and consolidated over a period of time in order to be susceptible to restructuring that constitutes the essential limitation in attempts to externally induce this restructuring by means of short-term experimental procedures” (p. 843). The transformative process can be difficult to capture due to its sometimes gradual and indistinctive nature.

Facilitating true transformation as an emergent process seems to precede the process of moving through the stages of change. For instance, the decision to lose weight, if it is to be truly motivating and result in true transformation of the individual, would first emerge from the transformative process. Within the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska et al., 1986; Prochaska et al., 2008) the opportunity for the transformative process exists in the stages of contemplation and preparation. As well, Kubler-Ross’s model (1969) represents an aspect of the transformative process in that acceptance of a loss (like “releasing old ways of knowing” in our model of transformative learning) enables the individual to see more clearly the path he or she must now take to continue living a full life. Scire (2007) later applied Kubler-Ross’ model to organizational change and found that, for some, a change in circumstances does not always have to be negative, but can prove to be a positive opportunity. Accepting a new job may cause individuals to lose their routine, workplace friendships, and confidence in tasks, but with this change may come the opportunity for learning, improved career prospects, salary, and benefits.

Schein (1999) illustrates the power of negative emotions and the importance of addressing them as part of the transformation process:

Adapting poorly or failing to meet our creative potential often looks more desirable than risking failure and loss of self-esteem in the learning process. Learning anxiety is the fundamental restraining force which can go up in direct proportion to the amount of disconfirmation, leading to the maintenance of the equilibrium by defensive avoidance of the disconfirming information. It is the dealing with learning anxiety, then, that is the key to producing change. (p. 55)

In dealing with these anxieties, Schein calls for the creation of psychological safety through a supportive environment and reassurances.

Again, proponents of a negative psychology may miss the opportunity that the negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety, worry, and concern, offer the facilitator. At the same time, they miss the opportunity to integrate positive with negative psychology. People protect what they love. Within their fears and anxieties lie their deep (and protected) values. Paradoxically, fears exist because of goals and values. The process of exploring competing commitments, negative emotions, or fears and concerns can do more than simply allow individuals to work through their emotions. In fact, this process may hold the key to transformation. By inquiring into fears, we are able to uncover deep values and goals.

The power of goals and values has been illustrated empirically (Locke & Latham, 1990). As an individual’s goals and values emerge, solutions to the “disorienting dilemma” emerge and the path of transformation becomes clear. For instance, Kegan and Lahey (2001) provide an example of a woman whose competing commitments included “wanting a project to succeed” and “not wanting to override her boss’s position in the company”. If her fear of overriding her boss’s position were to be explored, it would be clear that she deeply valued her relationship with her boss. The transformation in both behaviour and outlook would occur when her values become clear; having gained insight into her true values, she can proceed with her project after having a respectful conversation with her boss preparing him for the possible change in their relationship. As Jung reminds us, “in the intensity of the emotional disturbance itself lies the value, the energy, which (the individual) should have at his disposal in order to remedy the state of reduced adaptation” (Jung, 1957/1969). The solution may lie within the problem.

The key to moving past the crux, and creating true readiness for transformation, may rest with an integration of theories. Paradoxically, the power of positive emotions in driving transformational change may begin with the power of negative emotions and resistance. Resistance to change may hold the “seeds of change” in that within our fears and anxieties reside our true values. While values have been shown to be a powerful motivating force, stress and fear are just as powerful at diverting attention away from values. If our fears represent the values we aim to protect, inquiring into fears would expose the values that can drive change.

For this study, we were interested in exploring the student experience of a transformative learning approach to education—one that challenges the typical educational processes, contexts, and elements. From these insights, we hoped to discover ways to better facilitate the transformative learning process for our learners through our learning and teaching model.

Research Approach and Data Collection Methods

This study is interpretive. The researchers’ ontological assumptions are that reality is “socially constructed, complex and ever changing” (Glesne, 2011, p. 8). An interpretive epistemology (Cresswell, 1998) seeks to understand how people experience and make meaning of their experiences within this socially constructed world. This approach enabled the researchers to make sense of the data—that is, how students experience transformational learning at RRU. This study is a narrative inquiry in which we elected students’ stories related to their learning experiences at RRU. “The study of narrative is the study of the ways humans experience the world” (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990, p. 2). Narrative is a “form of discourse in which the events and happenings are configured into a temporal whole” (Kelly & Howie, 2007, p.137), capturing context-rich and situated understanding. The study examines how students make meaning of and integrate the University’s learning and teaching principles into their learning experience. It uses narrative inquiry to explore new students’ experiences, their challenges, and what supports their learning. We elicited students’ stories through a survey with open-ended questions to gain insight into their learning processes, and ultimately, to develop strategies and processes to support students as they “transform” through RRU’s pedagogy.

Approximately 560 students in the Master of Arts in Educational Leadership and Management (MAELM), Master of Arts in Professional Communication (MAPC), Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication (MAIIC), and Master of Arts in Leadership (MAL) programs received an invitation to participate in an anonymous survey to elicit their perceptions and stories, which were analysed for themes and insights into their meaning-making processes, and transformational learning experiences. We asked:

- Can you recall a time during your experience at RRU when you felt that the learning experience/model/approach was different? Tell us about that; what happened? What made it different in your opinion? What stuck out particularly? What discovery did you make about yourself and/or RRU? What prompted this discovery?

- How did you experience this difference in learning experience/model/approach? Can you recall a time during your experience at RRU when you felt a particular shift in your learning style, assumptions about learning, mental models or even world view? Describe the events surrounding that experience; what happened and what did you notice about yourself? About learning? Can you recall a tension, a conflict, an incongruity OR a release, an alignment, a familiarity with the learning and teaching model at RRU? Describe the experience.

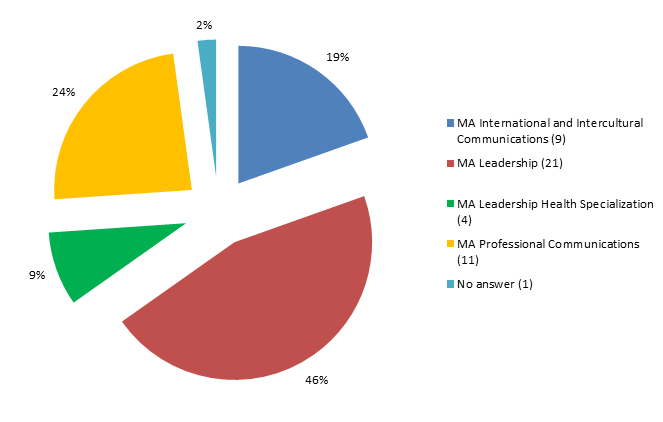

We received a total of 93 responses. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of responses by program.

Analysing narrative data is not a process that emerges from “a single heritage, theoretical orientation or standard methodology” (Kelly & Howie, 2007, p.139). Rather, it draws on a variety of qualitative methodologies in order to bring to light the depth of meaning embedded in the narratives and how their interpretations shape future practices. Clandinin and Connelly (2000) describe narrative analysis as a process of transforming field texts (in this research captured in interview transcripts) into interim texts (interim analyses), followed by research texts (documents ready for dissemination). We examined the field texts for “the patterns, narrative threads, tensions and themes within an individual’s experience and in the social setting” (p. 132).

Results and Discussion

The themes emerging from the data reflected the transformational learning model introduced earlier in the paper. We’ve used the words of the students themselves (in italics) to illustrate our findings.

a) Disorienting dilemma

Many students remarked on what was different about the RRU model and approach:

The learning experience is constantly/consistently different from my bricks & mortar undergraduate experience, and also other distance graduate experiences that I’ve had.

I’ve had experience in distance graduate learning, so I knew what to expect on many levels… but not necessarily what to expect from RRU.

What was different is that my cohort members were so much more a part of my learning.

…the integration of on-campus residency with online learning, which is not incorporated into many other distance learning programs.

When I started the program I found that the information was not merely being dumped on us, it was made available.

For the remainder of residency everything was different. It wasn’t all lecture style. We were learning about ourselves. We were not just learning from the teachers, but from our classmates too.

I completed my undergrad through distance education at another university. It was an individualized study and therefore I did not have the experience/benefit of a cohort model.

The RRU experience was a much richer one in that I had far more interactions with faculty than I had previously.

The emphasis on getting to know each other, feeling comfortable, and being able to help each other stuck out in each plenary and seminar session, which in turn translated to a close-knit community outside of the classroom.

Although theory was taught in the classroom, there was an application piece during my residency in China that was unlike any other learning I have done.

Unlike many students, I completed my undergraduate degree mainly through a distance program. What I found different in this program, which helped with my learning of the content, were the online discussions with my cohort.

While most students spoke of these differences in a positive light, often the difference they sought resulted in a tension they then needed to resolve. Students celebrate differences while at the same time experiencing a “disorientation” and struggling to function within these new and different educational parameters. The result is feeling caught in a “dilemma” of wanting something different from past “bricks and mortar” experiences, yet not having the tools or mindset to respond to this new environment. For instance, students want an approach that allows them to continue working—an approach RRU describes as “meeting the needs of the working professional,”—yet struggle with the resulting lack of time or balance:

There has not been enough break time between courses. It is unreasonable to give people only a week between courses who are working full-time. It accomplishes very little except excessive stress and exhaustion. RRU’s learning model, in my opinion, is seriously flawed in this aspect.

I struggled with the work-life-school balance and it had a significant impact on my stress level.

Students also signed up for a more mature, diverse cohort of working professionals, yet then struggled with how this model contradicts a more established profile of a graduate student or master’s level program, or even what learning involves—i.e. that learning cannot happen with those who do not have the same “level” of education or experience:

What was different is that my cohort members were so much more a part of my learning.

One of my biggest challenges was with my mental model of what I considered to be a master’s caliber student.

My tensions were mostly derived from the others in my cohort—this may relate to RRU’s acceptance practices, but there were a number of people who clearly did not add to the experience of others… in fact there were a few who detracted from our learning experiences as a cohort.

The students were seeking autonomy and an adult learning experience at RRU, yet wrestled with the independent self-direction required:

There is far less engagement with the professors during the off-campus terms, which creates a distance between me and my studies.

What prompted this discovery was a baptism by fire so to speak, as we all were intentionally teamed up in diverse groups with all the information collectively to successfully complete the various assignments.

I did not expect to have to reach so far into myself, and to challenge my own way of being as much as I did.

At first it was a bit overwhelming getting to know the technology, etc., but then I got used to it.

Students, though craving an alternative, more democratic learning environment, seemed bound by the constraints and expectations of a traditional hierarchical learning environment. As one student remarked, the cohort as a whole seemed reluctant to embrace the true democracy and openness required within the discussion forums, despite the online nature of the program and its associated adult learning principles:

While the intention is good, I’m personally finding the asynchronous posts are a bit contrived—they tend to be answers to questions on material and not conversations to fully explore and test out ideas and theories. I don’t feel they are “safe” enough to openly make errors for learning.

Students seemed locked in a traditional view of university hierarchy, and some were unable to let go of preconceived notions of power and control in an educational setting. Students continued to assume that their instructors were adversaries rather than partners, or that they had no alternative avenues for raising concerns other than the traditional “chair” position:

I also feel that to have the Department Head instruct courses is unacceptable and unworkable because there is a power imbalance and vulnerability should a student feel compelled to challenge that person on marking or other issues that arise.

Though students applied to RRU for its unique model and approach to adult post-secondary learning, flexible admissions, and cohort model, these were the very elements that proved “disorienting,” challenged the students, or caused tensions. Many students were unable to reconcile their prior experiences and expectations of higher education with the unique, alternative learning environment and elements offered by RRU. As an institution, it is important to not only confront students with a new model, unique educational principles, and more democratic approaches, thereby “disorienting” them, but also to equip students with the tools to resolve the tension between the RRU model and their previous, traditional experiences and expectations, shift their mental models, and transition them into a new way of operating through reflection and practice. For instance, RRU instructors could facilitate discussions concerning learning and challenge students to consider and articulate the ways we can learn from individuals who derive from all demographics of society. Instructors could be more intentional about helping students recognize their disoriented state, and then provide students with the opportunities and tools to reorient themselves within their new environment.

b) Threatening or challenging opportunity to reflect

Based on the literature concerning transformational learning, a necessary step in the transformative process is the emergence of a threat or challenge. While the students noticed “differences” and found these “disorienting,” critical to transformational learning is that these disorienting dilemmas are also threatening or challenging in some way, forcing one to appraise, reflect, and respond. The students articulated many thought-provoking threats and challenges:

The thing I found most frustrating about the RRU experience was the diverse background of my cohort members.

… one person in my advisory group stood out significantly, and quite honestly, made me question whether I wanted to consider my RRU journey because I did not want to feel I had an “under-rated” degree, especially for the cost.

Overall, the setting that we work in has allowed me to come into contact with many interesting people and has often tested my ability to work with people I wouldn’t normally choose to work with. This has been a huge part of my learning as a master’s student and as an individual in relationship.

Students often commented on the level of their peers’ academic or professional achievement or status, referring to their educational and career accomplishments. For some, the diversity of the cohort posed a challenge by “testing their abilities to work with the unfamiliar,” and for some it posed a threat to the quality or “reputation” of their degree. The challenge or threat posed by the diverse cohort offered an opportunity for reflection on what makes a colleague or peer, a quality degree, or a productive team-based learning experience.

As well, students found the vulnerability of the online environment a challenge or threat:

I noticed that during the first semester with the online learning discussions I was sensitive to critiques or comments from my peers.

It is a point of potential humiliation if you are on the wrong track. Posting does force you to assemble your thoughts and read others, and allows for distance across time zones.

For students, the challenge emerged when their independent learning began to suffer from a tendency toward and expectation of “dependence” on the instructor:

I think that the vacuum of learning on a laptop alone becomes a point of tension in its ambiguity – students are floating in a sea of content without direction or feedback.

There was no catalyst (i.e. lectures or live discussions) to push us in to engaging with the material, the concepts, the theoretical structures. We miss out on the seminar style discussion that really pushes a graduate group to learn and explore together… mostly due to the apathy of others, and the daunting nature of logging in to a forum and seeing dozens or hundreds of responses to read and acknowledge.

The traditional learning environment features a reliance on an instructor at all times to initiate and facilitate discussion and learning. The reality of adult learning includes interacting with and learning from one’s peers as much as an instructor, initiating discussion independently and creatively, and choosing to follow or contribute to particular threads from myriad discussions. The challenge that this bereft student experienced offered an opportunity to reflect on the true nature of learning and the learning environment. S/he could have abandoned the learning as undemanding due to the lack of instructor “push,” as this student realized:

This experience did teach me about what types of learning I want to pursue in the future – that I want to avoid group-based learning, and collaborative assignments; that I want to focus on research that is important to me; that a “traditional” bricks & mortar learning environment is a more comfortable place for me.

Or students could choose to reflect on and question their expectations as a way to consider and imagine alternative ways of knowing and learning. As one participant articulated:

We could either be victims of circumstance, or become self-aware and recognize the systems at work.

Both the institutional communicators and the instructors at RRU could be more intentional about surfacing the challenges and threats that a new learning model and environment pose to students. Embracing and welcoming the critiques and highlighting the differences between the RRU and traditional models would wake students up to their assumptions about learning and begin the transformational process. Instructors could then facilitate a discussion about expectations, gaps, and what is missing from the RRU experience, thereby fostering critical reflection on the traditional models of learning and challenging students to consider that there may be alternatives to “pushing students”. Learning can also be a pull, a listening to one’s inner drive, and a self-propulsion.

c) Conscious choice to reflect and problem solve

Many students reflected the next phase of transformational learning in their comments regarding the conscious choice to pause, reflect, and problem solve the tensions, incongruities, and discomfort they were experiencing:

During these sessions you gained incredible insight into differing perspectives if you were open to understanding these perspectives.

Several students were acutely aware of the turning point that these uncomfortable experiences offered, and emphasized the need for all students to “trust the process” in order to arrive at true insight and understanding:

I can state that those who did not (trust the process) encountered a difficult path of completing program/course requirements.

Trusting that the School has your best interests in mind is something that a lot of students need to realize. If you’re coming into a cohort model thinking that life is all about you, and you alone, you’re screwed. It is truly a team effort between yourself, the cohort, the academic team, and the administrative team. However, when it comes to the work and increasing your knowledge base and capacity, the work you put into it reflects what you will receive!

Personal reflection occurred independently, prompted by a dilemma, tension or threat, and often resulted in self-discovery or a new appreciation for possibilities not otherwise imagined:

I think that the setting in which we were exposed to other people in our program and the variety of people and backgrounds in the program allowed me to do a lot of self- work as well as progressional [sic] development.

Within the process, one essential piece included relying on the group you were partnered with to supply information from their learning towards overall group understanding and project completions.

When we did have seminar-style discussions I found some of my cohort were an immense help in allowing me to adjust my frame of reference.

Adult learning principles suggest that students are agents of and engaged in meaning making. For example, this student realized on her own that materials were often recommended and not required, curated, and stored for future reference, rather than deconstructed by the instructor through lecture:

This meant I could return to it instead of trying to memorize and regurgitate, allowing for real understanding and cognitive function.

A common expression at RRU is the “aha moment”. Prompted to reflect on what was important to them and to question their prior learning and experiences, the students worked through their concerns independently and thoughtfully arrived at new insights and deeper self-understanding perhaps not possible unless experienced independently:

What discovery did this prompt? That I needed to make this program my own – that it wasn’t designed to offer me what a bricks & mortar program provides. In order to get what I wanted from the program I needed to put in extra time for theory and introspection to have the academic understanding of concepts that I felt was warranted in a graduate program.

This is crucial learning for me; I have some background in interactive multimedia training and am learning first-hand the importance of integrating a variety of learning elements. It is easier to tune out when course content is static and self-paced; engagement is lower and learning isn’t as embedded.

The most valuable role the RRU instructor can play in facilitating the transformative process is likely in providing students with the opportunity to truly experience the challenge or threat to their value systems and expectations, and then to offer a space or opportunity to reflect upon that experience, make sense of it, and question the underlying values at stake. Instructors could inquire into what is threatened or at stake for the student in an effort to surface the values they seek to protect and sustain. Instructors can challenge students to articulate their underlying values in an effort to raise awareness.

Students can then be challenged to build their values within the new RRU context. For instance, for those students struggling with the independent nature of adult learning at RRU and the lack of push, it may become clear that development and growth are what is most at stake. Asking the learner to consider how they might develop and grow in an environment that does not involve being “pushed” will encourage him or her to imagine the alternative (i.e., self-directed learning, ownership of one’s learning, and independent exploration) and let go of his or her default expectations.

d) The questioning of assumptions

Surfacing and questioning assumptions emerged as a natural part of the transformational learning process at RRU:

Well, I have had a shift in a major way. I took a lot of things at face value, I won’t say I am cynical now but life experiences and situations trigger a lot of questions for me…

As part of the transformative process, individuals first encounter a disorienting dilemma that awakens them to the difference and creates a cognitive dissonance. They may interpret some elements of this experience as threatening or find the experience challenges their prior learning or ingrained expectations. At this point of cognitive appraisal, individuals may decide to reflect upon the feelings of discomfort or unease and then make a conscious choice to problem solve. It is at this point of choice or dilemma that an instructor can play a critical role. Often, the individual needs to recognize that a threat is not necessarily a signal to fight or flight but can also be an opportunity for self-awareness, development, and growth:

Recently I had another shift in my assumptions about the world, about others. In order to change the experience I was having with my sponsor I chose to look at the situation from an entirely different angle. To change my mind about him and it.

When an individual recognizes the threat as an opportunity and enters into an exploratory problem-solving process, underlying assumptions become more visible (Kegan, 2000). For instance, initially a student may struggle with the cooperative, collaborative approach to learning, and rail against the risky and somewhat self-effacing nature of such an approach:

One of my greatest learnings has been about sharing. In the corporate world you are careful about what you share because it is through your creativity and uniqueness that you get ahead. Some value is placed on leadership but mostly it is about being better than the next person.

The shift in thinking from confronting a “threat against which to defend” toward “an opportunity” to reconsider old ways of knowing and reimagine new ways of doing is coupled quite naturally with a surfacing of assumptions about what was “right” or “necessary”, a demonstration of true critical thinking:

I have learned to feel really comfortable being a leader and helping the other person any way I can. I recently shared my entire proposal to a group struggling, never once feeling that I was ‘losing’ but rather that I was gaining because I had helped them.

I feel safe and at home with this community and that has allowed me to take risks and be vulnerable in my learning to a degree that I did not expect would have been possible.

Along with the awareness of assumptions and the realization of one’s faulty or narrow thinking comes a greater awareness of alternative possibilities:

…that introverts are able to be tremendous leaders!

…that I was getting smarter, this is done by realizing how little I know, day after day.

…that I don’t know as much as I thought or think I know but am always seeking to know. I love it.

…that I’m not as independent a learner as I thought I was.

Some students came to realize that the source of their greatest initial disappointment and frustration—the “quality or level” of their peers—became one of the greatest sources of learning and inspiration:

I came to the conclusion that we are on our own journey. I had much to learn as did this person, and therefore RRU may be the right institution. I was on my journey, she was on hers.

One of the biggest changes in my thinking that I noticed was being able to look at an issue from different perspectives and being open to a change in my thought from that assessment.

At this stage in the transformative process, RRU instructors could play a role in helping the students to acknowledge and articulate more specifically the assumptions guiding their prior learning. Raising awareness about assumptions in general is a powerful educational tool and a necessary step in developing a student’s capacity for critical thought. Once assumptions are made visible, it is possible to recognize and surface assumptions in other contexts. However, instructors must also understand that assumptions can only be made visible once the student has moved several steps along the path of transformation. Students must be ready to see assumptions first and this takes an appreciation for the process, and timely facilitation along the way.

e) Releasing old ways of knowing

Releasing old ways of knowing is the point of actual transformation that was set up in the categories a-d. It involved the learners’ realization that their existing perceptions about learning would no longer serve them. To learn in the RRU Learning and Teaching Model environment, learners needed to actively engage with what they were learning, to make meaning of it, and apply it in their workplace. The following learner’s reflection states succinctly the before and after states of knowing that the “release” brings about:

I have shifted my mental model about learning. I am not exactly sure at what point along the way it happened. I came in with the view that the instructor would relay information and knowledge and that I would take it in and would then have learned what I was supposed to. This is not at all what happened. I was guided to resources, but then asked to offer my own thoughts on what it meant and to connect it to how I perceived it to be relevant to my work.

Another learner described his sense of “release” when he realized the limitations of his old way of learning and his need to “escape” from a limiting approach to a new “culture” that would serve him:

A release of sorts is accurate in describing a point in time during the learning where I realized how I had been living, thinking, acting, and feeling had been impacting or controlling my path to date. Escape from the present culture I had been a part of was the immediate course of action, followed by realization that escape could not be permanent. The path forward needed to embrace intentional integration of what had been learned to form part of creating a new culture which I would be glad to be part of.

When learners described the “release,” they often contrasted the “before” with an “after” state describing their own agency in learning. For example, a learner stated:

I needed to make this program my own – that it wasn’t designed to offer me what a bricks and mortar program provides. In order to get what I wanted from the program I needed to put in extra time for theory and introspection to have the academic understanding of concepts.

In each case, the release came when students let go of their past learned behaviours, perceptions, or expectations related to how one learns. Their “letting go” led directly to taking on an active role of meaning making and integrating what they were learning with prior knowledge and practice.

f) New level of consciousness or insight

Participants described new levels of insight in two major categories: insights about themselves and their learning; and insights into the value of connectedness and peer support inherent in the learning community.

Insights into self

Participants described insights into their own abilities that were tested in the learning environment. For example, one learner stated:

I learned about my own tenacity, discipline, team-work capabilities, strengths, and intellectual endurance.

In contrast, others pointed out the link between the personal and the professional. A participant described the learning process as one of maturing:

The learning model made me grow up and become more engaged in my personal and professional life.

Another participant also describes this link between personal and professional insights but notes that this type of learning may not be suitable for all:

The learning was holistic and led to a deepening of personal and professional discoveries for me as a student. This type of learning may not be suitable for everyone, however, I found it to be very effective and had a significant impact (positively) on my overall experience at RRU.

This learner notes that while the learning process had positive outcomes for him, it may not for all learners. This statement supports the idea that learners need to make a conscious choice to reflect and problem solve, and to question their assumptions (as shown in sections c and d).

For some participants, the insights were described in terms of responsibility for learning and control, as demonstrated in the following quotations:

The distance learning element forces you to take matters into your own hands. You get in what you put in, and you learn to take full responsibility for your experience and your outcomes.

The recognition that I had control (when sometimes it felt like I didn’t) and the only one who would ultimately make or break my success was myself.

In contrast, another participant realized that accepting and working through uncertainty was far more important to learning and dealing with changes in the workplace:

What I learned about myself is that I need to trust my instincts more and not panic when things do not go as planned. Sometimes, it is perfectly acceptable to just stand in uncertainty. Learning that has served me well through many organizational changes at work.

Participants’ experience of the type of learning engendered by RRU’s Learning and Teaching model was deeply personal, even revelatory. As the participants’ comments demonstrate, the RRU Learning and Teaching Model approach led to professional as well as personal learning. And, once learners obtained new levels of insight or consciousness, that approach to learning continued. One participant stated it succinctly:

I know that my world view will never be the same as a result of being in this program… I have learned more about myself than ever before and paradigm after paradigm keeps shifting, most unconsciously, which speaks to the many positive aspects of this program and RRU.

Insights into the benefits of the learning community

The Learning and Teaching Model acknowledges that learning is social and thus, supports the development of a supportive learning community among students. It therefore came as no surprise that participants’ insights were about the benefits of “sharing,” “mutual support,” and “networking.”

One participant described how she bonded with her cohort:

Perhaps it was the subject matter (Leadership) that made the course so personal, but I was amazed at the strong bonds I was able to form with the cohort prior to meeting them in person.

Others noted how learning in “community” enriched their learning:

Just as I was learning from others, I recognized that they were learning from me. How empowering! This “community of practice” (my label for this) generated synergy, and the level of outcomes far exceed what I could have achieved on my own. Profound!

I feel safe and at home with this community and that has allowed me to take risks and be vulnerable in my learning to a degree that I did not expect would have been possible.

Similarly, a participant noted that she was learning a new way of learning:

The class [members] sit in a circle and share information with each other and the class in ways that were strikingly different than the typical classroom setup. The result was learning new ways to consume and share information and ideas. Really powerful!

In addition to changing the way of sharing information through the group, this approach led to the development of a network that would last beyond the program:

This model has shown us that no one is going through this experience alone. We now not only have a great support system in each other, but also have built an incredible network that will last years.

Mutual support and learning in community, two elements of RRU’s Learning and Teaching Model, created powerful learning environments.

g) Feeling of excitement or satisfaction and freedom as well as sadness

Some participants described a shift in their emotions as they confronted and made meaning of a different learning model that changed their role as a learner. For example, one participant stated:

The energy shifted to support my own personal journey from one of frustration, anger, disappointment, and wanting to slip into revenge to one that was peaceful, joyful, reflective and curious.

This extreme change of feelings shows how emotionally difficult, but ultimately rewarding, the learning journey can be. Participants used “love” to describe a shift in their way of learning, along with a lasting change. For example, a participant noted:

I have loved this experience. I have shifted my mental model about learning. I am not exactly sure at what point along the way it happened. I came in with the view that the instructor would relay information and knowledge and that I would take it in and would then have learned what I was supposed to. This is not at all what happened.

h) Enduring change

What is apparent in the participants’ comments so far is that the changes they experienced went well beyond the classroom to influence both their personal and professional lives. The transformational learning model describes here not only the aspects of participants’ lives that were altered, but also that the transformation led to enduring change; we found evidence of this in the participants’ story. For example, a participant stated that:

The residency will always stand out in my memory of life-altering events.

Another described how her self-examination led to transformation:

I think the best way to develop is through transformational learning, and having different ways to self-reflect is a key to examining mindset and then having the opportunity to shift. This is where long lasting significant change happens in my experience. There was time for that to occur. This was an alignment of the work I have experienced previously, supporting a process where the student continues to self-examine and then choose new action steps based on that learning combined with a supportive environment guided by people who also had undergone a process of self-transformation.

Finally, a participant described both how the transformation is exciting and has changed her life path:

I cannot begin to express how enrolling in this program has positively and powerfully impacted my life on all levels. It is the best thing I have ever done and I am so grateful for the experience. I am definitely changed and I am in alignment with my life’s path more than I have ever been. It’s very exciting!

Conclusion

We asked how the Learning and Teaching Model influences the learning environment and experience of students. The students’ stories strongly support the existence of a transformational learning process that changed how they learned and had lasting application to both their professional and personal lives. The data supported the existence of all the eight elements of the transformative learning process from the initial disorienting dilemma to the transformation to a new and enduring state of insight or consciousness.

We also asked how students experience and resolve conflicts between standard and transformative learning models. As we have observed in our own teaching, the disequilibrium brought about as students struggle to make meaning of a learning environment that is meant to create a questioning of assumptions and ultimate transformation triggers deep learning, as predicted in the literature. For our participants, however, the reward was in the new consciousness. This study both affirms the approach and helps us to understand in more detail the student experience.

This increased understanding of the student experience will allow us to better support students on their learning journey. It became clear through the research that RRU could better articulate, leverage, and facilitate its learning and teaching model. Instructors and administrative leaders could become more educated in the principles of transformational learning, which would enable them to be more explicit in the rational for the RRU transformational model. Recruitment, marketing, admissions, and web materials could all reflect more explicitly the purpose and principles guiding the RRU model to ensure students are aware of what they are choosing to pursue.

During the learning process, instructors could be more intentional and better equipped to facilitate the transformational learning process including surfacing tensions and dilemmas, guiding students to articulate their cognitive dissonance, drawing out their appraisals of challenging situations, surfacing assumptions, and challenging students to resolve tensions, generate creative solutions, and imagine alternatives through guided questioning and through techniques such as Open Space, Integrated Focus, or Appreciative Inquiry. We also recommend faculty and staff attend development sessions in theory and facilitation techniques for the transformative learning process. We urge university leadership teams to make a concerted effort to structure the theory, language, principles, and models of transformational learning into program and course materials in order to spark discussion and reflection both prior to and during the students’ learning process. With more explicit articulation and embeddedness of the transformative learning models and principles, instructors are encouraged and equipped to more explicitly and intentionally discuss and foster transformative learning experiences in their classrooms and courses.

References

Adams, P. (2006). Exploring social constructivism: theories and practicalities. Education 3-13, 34(3), 243-257. doi: 10.1080/03004270600898893

Alford, M. (2012). Social constructionism: A postmodern lens on the dynamics of social learning. E-Learning and Digital Media, 9(3), 298-303.

Bailey, L.D. (1996). Meaningful learning and perspective transformation in adult theological students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

Bauer, J., McAdams, D., & Sakaeda, A. (2005). Crystallization of desire and crystallization of discontent in narratives of life-changing decisions. Journal of Personality, 73(5), 1181-1214.

Baumeister, R. (1994). The crystallization of discontent in the process of major life change. In T. Heatherton & J. Weinberger (Eds.), Can personality change? (pp. 281-297). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Baumeister, R.F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K.D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323-370.

Boyatzis, R.E. (2006). An overview of intentional change from a complexity perspective. Journal of Management Development, 25(7), 607-623.

Boyatzis, R.E., & Akrivou, K. (2006). The ideal self as the driver of intentional change. Journal of Management Development, 25(7), 624-642.

Boyatzis, R., McKee, A., & Goleman, D. (2002, April). Reawakening your passion for work. Harvard Business Review, 86-94.

Boyd, R.D., & Myers, J.G. (1988). Transformative education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 7, 261-284.

Busick, B.S. (1989). Grieving as a hero’s journey. The Hospice Journal, 5(1), 89-105.

Carew, A., & Wickson, F. (2010). The TD wheel: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. World Futures: Journal of New Paradigm Research, 42, 1146-1155.

Carpenter, C. (1994). The experience of spinal cord injury: The individual’s perspective—implications for rehabilitation practice. Physical Therapy, 74, 614-629.

Clandinin, D.J., & Connelly, F.M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Connelly, F.M., & Clandinin, D.J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(4), 2-14.

Cresswell, J.W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cunliffe, A.L. (2008). Orientations to social constructionism: Relationally responsive social constructionism and its implications for knowledge and learning. Management Learning, 39(2), 123-139.

Delors, J., Al Mufti, I., Amagi, I., Carneiro, R., Chung, F., Geremek, B., … Zhou, N. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Paris, UNESCO.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Collier.

Dirkx, J. (1997). Nurturing soul in adult learning. In P. Cranton (Ed.). Transformative learning in action: Insights from practice (pp. 79-88). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dirkx, J.M. (2000). Transformative learning and the journey of individuation. ERIC Digest, 223, 2-7.

Dirkx, J.M., & Mezirow, J. (2006). Musings and reflections on the meaning, context, and process of transformative learning: A dialogue between John M. Dirkx and Jack Mezirow. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(2), 123-139.

Duff, V. (1989) Perspective transformation: The challenge for the RN in the baccalaureate program. Journal of Nursing Education, 28, 38-39.

Ferguson, M. (1980). The Aquarian conspiracy: Personal and social transformation in the 1980’s. Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher.

Fowler, J.W. (1987). Faith development and pastoral care. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press.

Fowler, J.W. (1994). Keeping faith with God and our children: A practical theological perspective. Religious Education, 89(4), 543-571.

Fowler, J.W. (1996). Faithful change: The personal and public challenges of postmodern life. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Fowler, J.W. (2004). Faith development at 30: Naming the challenges of faith in a new millennium. Religious Education, 99(4), 405-421.

Fullan, M., & Scott, G. (2009). Turnaround leadership for higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Gordon, M. (2008). Between constructivism and connectedness. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 322-331.

Gould, R.L. (1978). Transformation: Growth and change in adult life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Hagberg, J.O. (2002). Real power: Stages of personal power in organizations. Salem, WI: Sheffield Publishing Co.

Hamilton, D., Márquez, P., & Agger-Gupta, N. (2013). Royal Roads University learning and teaching model. Retrieved from http://media.royalroads.ca/media/marketing/viewbooks/2013

/learning-model/index.html

Harris, B. & Agger-Gupta, N. (2015). The long and winding road: Leadership and learning principles that transform. Integral Leadership Review. Retrieved from http://integralleadershipreview.com/table-of-contents/?slug=january-february-2015

Havighurst, R. (1972). Developmental tasks and education (3rd Ed). New York, NY: Longman.

Havighurst, R.J. (1980). Social and developmental psychology: Trends influencing the future of counseling. Personnel & Guidance Journal, 58(5), 328-334.

Jung, C.G. (1957/1969). The transcendent function. CW, 8.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2001a) How the way we talk can change the way we work: seven sanguages for transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2001b). The real reason people won’t change. Harvard Business Review, 79(10), 85-92.

Kelly, T., & Howie, L. (2007). Working with stories in nursing research: Procedures used in narrative analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16, 136-144.

King, K.P. (2002, May). Journey of transformation: A model of educators’ learning experiences in educational technology. Paper presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Adult Education Research Conference, Raleigh, NC.

King, K.P. (2004). Both sides now: Examining transformative learning and professional development of educators. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 155-174.

King, K.P., & Cranton, P. (2003). Transformative learning as a professional development goal. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 98, 31-42.

Lewin, K. (1958). Group decision and social change. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Loder, J.T. (1981). The transforming moment: Understanding convictional experiences. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

McGregor, S. (2014). Introduction to special issue on transdisciplinarity. World Futures: Journal of new Paradigm Research, 70(3-4), 161-163.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education, 28, 100-110.

Mezirow J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Mezirow, J. (1995). Transformation theory of adult learning. In M.R. Welton (Ed.), In defense of the lifeworld (pp. 39-70). New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. In P. Cranton (Ed.), Transformative learning in action: Insights from practice (pp. 5-12). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley and Associates.

Neuman, T.P. (1996). Critically reflective learning in a leadership development context (Unpublished PhD dissertation). University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Newman, M.A. (1994). Health as expanding consciousness (2nd ed.). New York, NY: National League for Nursing.

Nicolescu, B. (n.d.). The transdisciplinary evolution of learning. Retrieved from www.learndev.org/dl/nicolescu_f.pdf

Pierce, G. (1986). Management education for an emergent paradigm (Unpublished EdD dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University.

Prochaska, J.O. (1979). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis. Pacific, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Prochaska, J.O., & DiClemente, C.C. (1982) Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Pscychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19(3), 276-288.

Prochaska, J.O., & DiClemente, C.C. (1986). Toward a comprehensive model of behavior change. In W.R. Miller & N. Heather (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors: Processes of change. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Prochaska, J., DiClemente, C., Velicer, W., Rossi, J., Heather, N., Stockwell, T., …& Davidson, R. (1992). Criticisms and concerns of the transtheoretical model in light of recent research. British Journal of Addiction, 87(6), 825-835.

Prochaska, J.O., Norcross, J.C., & DiClemente, C.C. (1994). Changing for good. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Prochaska, J.O., Butterworth, S., Redding, C.A., Burden, V., Perrin, N., Lea, M., …& Prochaska, J.M. (2008). Initial efficacy of MI, TTM tailoring, and HRI’s in multiple behaviors for employee health promotion. Preventive Medicine, 46, 226-231.

Prochaska, J.O., Reddin, C.A., & Evers, K. (1997). The transtheoretical model of change. In K. Glanz, F.M. Lewis & B.K. Rimer (Eds.), Health behaviour and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Prochaska, J.O., Velicer, W.F., Rossi, J.S., Redding, C.A., Greene, G.W., & Rossi, S.R. (2004). Impact of simultaneous stage-matched expert systems for multiple behaviors in a population of parents. Health Psychology, 23, 503-516.

Prochaska, J.O., Velicer, W.F., Redding, C.A., Goldstein, M., Rossi, J.S., & Sun, X. (2005). Efficacy of stage-matched expert systems in primary care patients to decrease smoking, dietary fat, sun exposure, and relapse from mammography. Preventive Medicine, 41, 406-416.

Prochaska, J.O. & DiClemente, C.C. (1986). Toward a comprehensive model of change. In W.R. Miller, & N. Heather (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors: processes of change (pp. 3-27). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Scheiern, K. (2006). Transformational dynamics: Documentation and analysis of the effectiveness of a program/model created to engender behavioral change in individuals (Doctoral Dissertation). Dissertation Abstracts International, Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 65(5-A), 1866.

Schein, E. (1999). Process Consultation Revisited. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Schein, E.H. (1999). Kurt Lewin’s Change Theory in the field and in the classroom: Notes toward a model of managed learning. Reflections, 1(1), 59-74.

Skar, P. (2004). Chaos and self-organization: Emergent patterns at critical life transitions. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 49, 243-262.

Smith M.J. (1984) Transformation: A key to shaping nursing. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 16(1), 28-30.

Taber J.A. (1983). Transformative philosophy: A study of Sandara, Fichte, and Heidegger. Honolulu, HI:University of Hawaii.

Taylor, E.W. (1994). Intercultural competency: A transformative learning process. Adult Education Quarterly, 44(3), 154-174.

Taylor, E.W. (1998). The theory and practice of transformative learning: A critical review. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University.

Tawil, S., Akkari, A., & Macedo B. (2012). Beyond the conceptual maze: The notion of quality in education. Paris: UNESCO Education Research and Foresight (Occasional Papers No. 2).

Tawil, S., & Cougoureaux, M. (2013). Revisiting learning: The treasure within. Paris: UNESCO Education Research and Foresight (Occasional Papers No. 3).

UNESCO (n.d.). Education for Sustainable Development 2005-2014. Retrieved from http://menntuntilsjalfbaerni.weebly.com/uploads/6/2/6/2/6262718/unesco_5_pillars_for_esd.pdf

Wade, G.H. (1998). A concept analysis of personal transformation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2(4), 713-719.

Watson, J. (1989). Transformative thinking and a caring curriculum. In E.O. Bevis, & J. Watson (Eds.), Towards a caring curriculum: A new pedagogy for nursing (pp. 51-60). New York, NY: National League for Nursing.

Wickson, F., Carew, A., & Russell, A. (2006). Transdisciplinary research: characteristics, quandaries and quality. World Futures: Journal of new Paradigm Research, 38, 1046-1059.

Wildemeersch, D., & Leirman, W. (1988). The facilitation of the life-world transformation. Adult education quarterly, 39(1), 19–30.

- Our thanks to our colleague Niels Agger-Gupta for enriching this section on constructivism and social constructionism as they apply to the Learning and Teaching Model. ↵

- We acknowledge differences amongst these theorists and many others. In this article, we focus on the shared characteristics of constructivism. ↵