Local Public Services

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the many services local governments provide that you depend on

- Understand how public services differ from private services people buy for themselves

- Describe how you can influence what happens in your community

Consider some of these everyday activities:

- You turn the handle on the faucet, and water flows into your glass.

- You put your trash out, and it is picked up and carried away.

- You swim in the pool or play ball at the park.

- You call the police or sheriff about a break-in at your house, and an officer comes to investigate.

Safe drinking water, regular trash collection, recreational opportunities, and police protection are among the many services provided by local governments. You and your family likely utilize some of these services—water, for example—many times each day. Other services, such as trash collection or recreation, may be used only once or twice a week. Still other services—criminal investigations, for instance—may be used only rarely but are available when you need them.

What makes a service public?

Public services are the activities, products, and facilities that benefit the community at large. Many services are private: the person who uses the service is the only one who benefits from it. Think of a haircut, for example. The person getting the haircut gets the benefit of it. In these cases, there is no need for public money or authority because people are willing to purchase the service for themselves. Some local public services, such as maintaining community parks, benefit both the people who use them directly and the wider community. Other services, such as stormwater collection, may have no direct users, but improve or protect the community in general. The key to what makes a service “public” is who benefits from that service. Think of streets and roads. Everyone in a community benefits from their availability, whether they use a particular street or not.

Many public services have both public benefits and direct users. For example, students are the direct users of the public schools. However, the entire community benefits from the education that prepares students to be good citizens and to earn a living. That is why government gets involved in providing the service.

We say that governments provide public services because they arrange to have the service produced and paid for. Local governments arrange for many services through government employees. In other cases, the government hires a private business, a nonprofit organization, or another government to deliver the service. When a public service is purchased from a business it is said to be privatized.

Many public services are paid for by a government from taxes the government collects for that purpose. For some services, local government charges users of the service a fee to help cover the cost of the service. For example, most governments charge their customers for the water they use because they get a direct benefit.

Types of Public Services

Regardless of whether public services are paid for from tax money or from user charges, it is helpful to distinguish between “user-focused public services” and “community-focused public services.”

User-focused public services provided by local government include:

- water supply;

Dog park, Wake Forest, N.C. - solid waste management;

- parks and recreation;

- police, fire, and emergency medical services;

- social services;

- health services;

- public schools; and

- streets and sidewalks.

User-focused public services have both individual and community-wide benefits. For example, you benefit directly when you draw water from your faucet, get rid of your trash, or swim in the pool. But these user-focused public services also benefit the community at large. Having a safe, abundant water supply protects everyone in the community from diseases spread by contaminated water and supports firefighting. Safe, efficient waste collection and disposal helps keep the community clean and attractive. Public recreation also supports community quality of life.

Community-focused public services have no direct users. Instead, the purpose of community-focused public services is to build stronger communities or protect the public from harm. This may involve a wide range of government programs such as picking up litter, offering incentives for business relocation, or banning smoking in public buildings.

Local governments often undertake projects to improve the community’s

- physical condition,

- economic condition,

- social relationships, and

- safety from crime.

To protect the public, local governments regulate

- people’s personal behavior and

- their use of property.

Often, people have more difficulty seeing the ways community-focused public services help them because they do not directly request the service or see how it affects them.

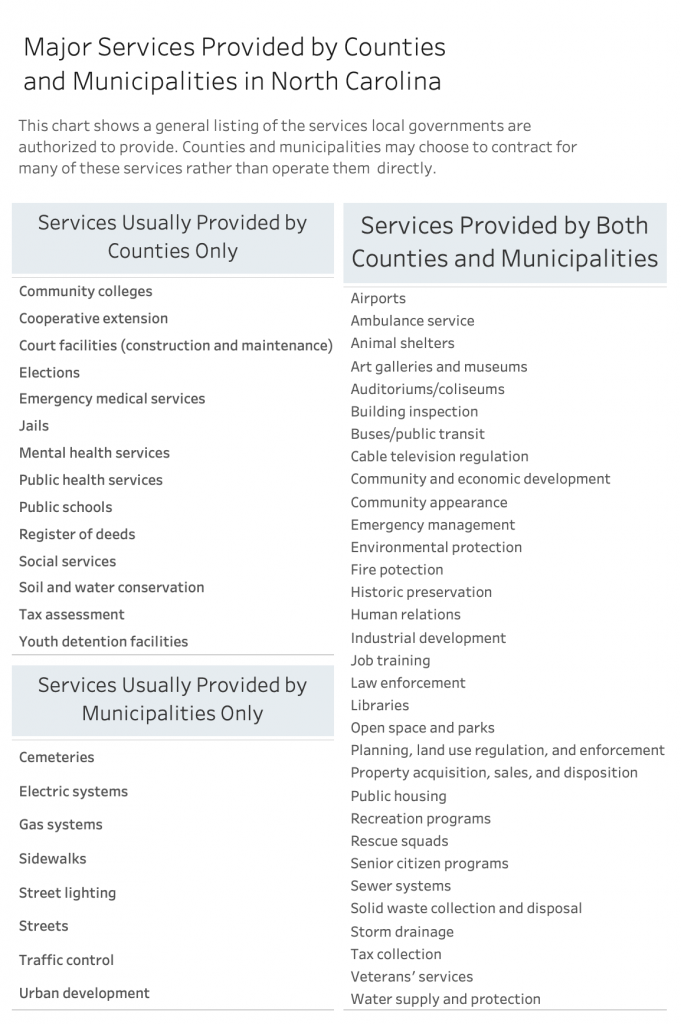

What Services Do Cities and Counties Provide?

Municipalities and counties provide some of the same services, but each type of local government also provides some services the other does not. The table below lists all the major services that North Carolina county and municipal governments are authorized to provide under state law. No single government provides all the services on this list.

Counties are required by state mandate to provide most of the services on the “county only” list:

- elections,

- social services,

- public health and mental health,

- public schools,

- emergency medical services,

- custody of deeds and vital records,

- jails and support for the courts and juvenile detention facilities,

- cooperative extension, and

- soil and water conservation.

Most counties also support community colleges.

Each county government is also responsible for assessing the value of property on which local governments levy taxes.

Municipal governments in North Carolina (but not counties) are authorized to provide streets and sidewalks, electricity, natural gas, urban development, and cemeteries. These services are optional for cities and towns to provide. Most municipalities do provide streets, sidewalks, and street lights, but few operate electric utilities and even fewer provide natural gas service.

More than 30 other local government services can be provided by either counties or municipalities. The General Assembly has given both kinds of local government the authority to arrange and pay for this broad set of public services. Local governing boards decide whether to provide these services, at what level to provide them, how to deliver them to the public, and how to pay for them.

This chapter addresses user-focused public services provided by local governments. Community-focused services are discussed in later chapters.

Water Supply and Wastewater Treatment

Supplying safe, readily available water is a key service of many local governments. Most cities and towns operate their own water supply and wastewater systems. An increasing number of counties have also begun to operate water distribution and sewage treatment facilities in unincorporated areas where wells cannot provide safe and abundant water or septic tanks are inadequate for safe disposal of wastewater.

Public water supplies provide safe drinking water and serve as a ready source of water for fighting fires and for supporting industries that require water in their production processes.

Public concern for safe water supplies dates from the late nineteenth century. In 1877, the General Assembly established the State Board of Health. One of its initial concerns was the threat of waterborne diseases in the state’s cities and towns. Intestinal diseases like typhoid are caused by bacteria that live in water. These diseases are spread by water that has been contaminated with human waste.

To help prevent disease, Asheville built a system to supply filtered water to its residents in 1884. Water from the Swannanoa River was pumped four miles from the filtration plant to the city. The year after it was built, the State Board of Health reported that Asheville’s new municipal water supply was the safest in the state and that there had been “a marked decrease in typhoid” in Asheville.

Not everyone in Asheville benefited from the new system, however. Although the city owned and operated the water-supply system, it charged 25 cents per thousand gallons of water. This was expensive for workers who supported their families on $300 per year. Asheville city water was, therefore, “not in general use among the poorer classes,” according to the Board of Health report.

In fact, Asheville’s water rates were lower than those in many other cities. Unlike Asheville, most North Carolina city governments did not operate water systems. Instead, private companies supplied water to city residents. In Raleigh, the private water company charged 40 cents per thousand gallons, and in Charlotte, the water company charged 50 cents per thousand gallons. Many people could not afford to buy water at these rates, so they continued to rely on unsanitary sources of water. During the twentieth century, public water supply, and many other services, became the responsibility of local governments. By 2000, almost all municipalities and many counties provided safe drinking water, water for fighting fires, and water for industrial uses.

Typically, local governments provide water and sewer services by setting up public utilities. In this arrangement, these services are paid for directly by the people who use them rather than by tax revenues. In recent years, some local governments have also set up utilities for storm water management.

Some cities and counties cooperate with one another in producing water or sewage services. Other counties, such as Catawba, loan money to local municipalities so that they can extend water service to unincorporated areas. In a few places, special water and sewer agencies or partnerships have been created by local governments to operate water and sewer facilities for the entire area. Examples include the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Utility and the Orange Water and Sewer Authority (OWASA).

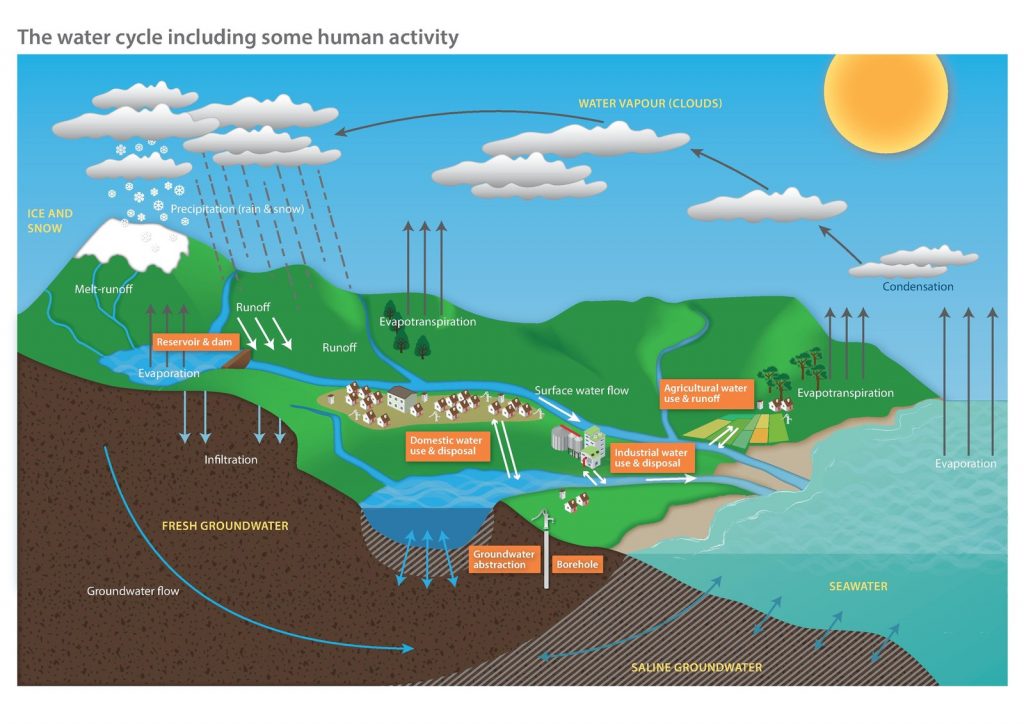

The water supply cycle involves several steps:

- developing a reliable source of sufficient water,

- treating the water to make it safe to drink,

- distributing the water through pipes to the places it is used, and

- controlling water pollution by collecting and treating wastewater (sewage) and managing storm water runoff.

Water Supply Sources

Wells are a major source of water in North Carolina, especially on the coast and coastal plain. Wells tap into underground water, allowing water to be pumped out of the layers of sand, gravel, or porous rock where it is trapped. In places where there are large pockets of underground water, wells can provide a steady source of water for public water systems. Rain and other water on the surface of the earth are filtered as they seep down to replace the water that is pumped out. In rural areas where there is no public water system, each house may have its own well.

In areas where ground water is abundant, local governments use wells to supply public water systems. At some places along the coast, sea water has seeped in because so much water has been pumped from the wells. In these places, local governments remove the salt from their well water through a process called desalinization.

Rivers and reservoirs are also important water sources for public water systems. North Carolina has many rivers. Rainfall ensures that they flow all year long, although sometimes a severe drought can cut the flow to a trickle. Some cities located near a river simply pump their water from the river. Sometimes rivers are dammed to create reservoirs from which water is pumped for treatment. Most of North Carolina’s larger cities, and many smaller ones, depend on water from reservoirs. Water from rivers, reservoirs, and lakes is called surface water.

Land that drains into a stream is called the watershed for that stream. Watershed protection can reduce contamination of surface water. Many local governments now have storm water management programs to catch the dirty water that runs off streets, roofs, and bare ground so that the pollution does not go into rivers and reservoirs. However, surface water is still likely to be more contaminated than ground water.

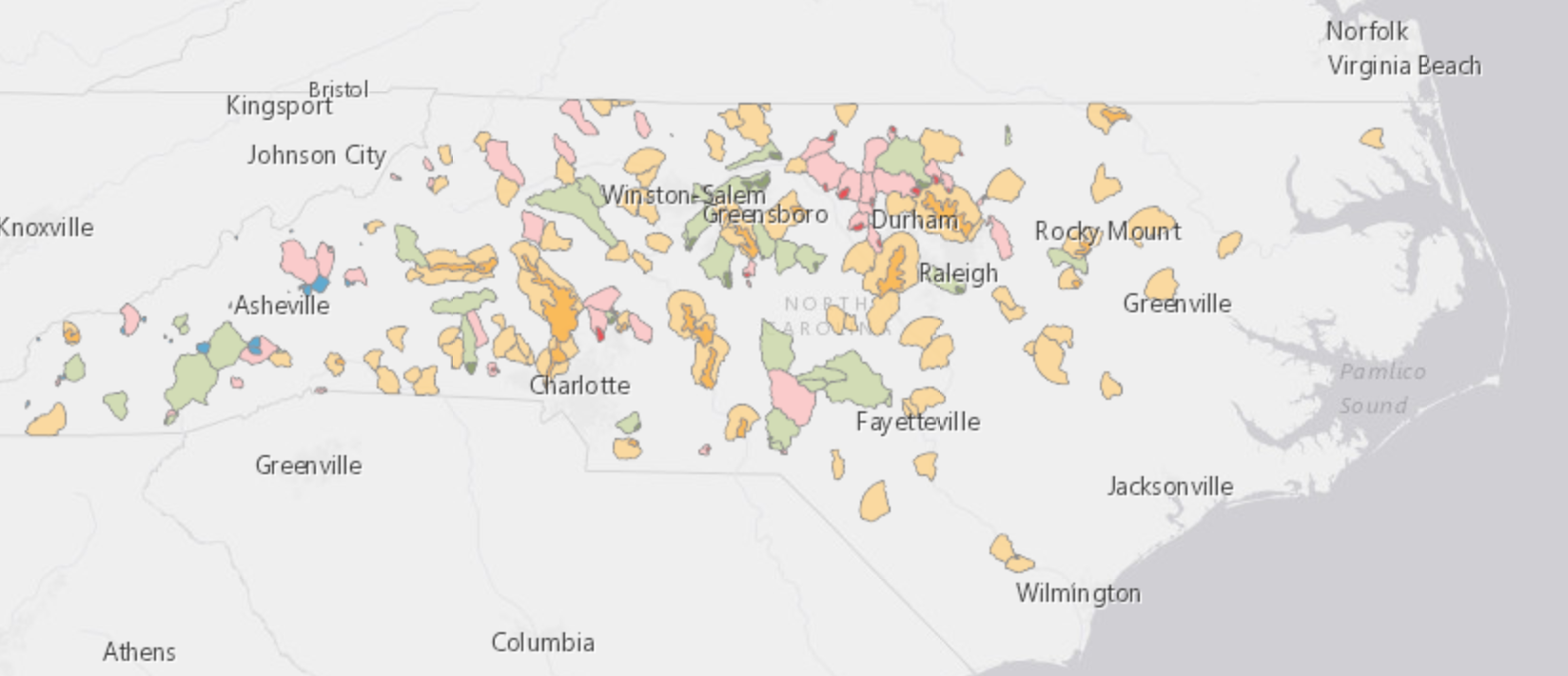

Water Supply Watershed Map

Where does your drinking water come from? Consult the interactive Water Supply Watershed Map to find out. Scan this code with the Metaverse App to open an AR experience.

Reservoirs are much more expensive water sources than rivers. Building a reservoir requires buying the land that will be flooded by the new lake and constructing a dam to contain the water. Engineers must first design a dam and map out the area the new lake will cover. Then the agency building the reservoir can begin to buy the land. Many reservoirs are built specifically to supply water. Some dams that provide water are built for other purposes, however. The federal government, working through the Army Corps of Engineers, builds reservoirs for flood control. Some private companies build reservoirs for electric power generation. If a city builds its own reservoir, the cost of the reservoir is paid by the customers who use the water. Thus, cities that must build reservoirs to ensure an adequate supply of water usually have higher water rates than cities able to get all the water they need from wells, rivers, or reservoirs that also serve other purposes.

The 3,000 acre Randleman Lake was created in the early 2000s by damming the Deep River. The lake and new water treatment facility on the lake was a project of the Piedmont Triad Regional Water Authority (PTRWA), a special purpose local government created by Randolph County and municipalities Archdale, Greensboro, High Point, Jamestown, and Randleman. The reservoir produces 48 million gallons of water per day, helping the region meet its water supply needs for an estimated 30-50 years into the future.

The 3,000 acre Randleman Lake was created in the early 2000s by damming the Deep River. The lake and new water treatment facility on the lake was a project of the Piedmont Triad Regional Water Authority (PTRWA), a special purpose local government created by Randolph County and municipalities Archdale, Greensboro, High Point, Jamestown, and Randleman. The reservoir produces 48 million gallons of water per day, helping the region meet its water supply needs for an estimated 30-50 years into the future.

Water Treatment

The kind of treatment water needs to make it safe to drink depends on how clean it is. Water from wells sometimes has almost no impurities. It has been filtered naturally as it collects underground. However, water can become contaminated underground if harmful substances are buried nearby.

To help prevent contamination of ground water, federal and state governments have passed several environmental protection regulations. One outlaws the discharge of dangerous chemicals into a stream or into the soil. Another prohibits putting toxic chemicals into landfills and requires landfills to be lined so that water cannot seep out of them and carry materials into the water. Still another requires underground storage tanks (such as those for gasoline) to be rustproof so they will not leak.

Surface water can also pick up many pollutants such as

- oil and grit from streets and parking lots,

- fertilizer and pesticides from fields,

- chemicals from trash or waste that is left exposed, and

- soil particles from bare ground.

Stormwater management can keep some of these out of rivers and reservoirs. Even so, surface water generally requires more treatment than well water.

The first step in treating surface water is to filter it. At the water treatment plant, filtering and sedimentation remove solid particles from the water. (Sedimentation involves adding chemicals to the water that cause the suspended solids to clump together and sink.) The water must next be treated chemically to kill harmful bacteria. Chlorine compounds are typically added to the water for this purpose. In many places, fluorine compounds are also added to the water to reduce tooth decay. Water plant operators must constantly monitor the water through each stage of treatment to be sure they are adding just the right amount of each of the chemicals they use.

All this costs money, so the cost of building treatment facilities and treating water is also a part of the fee a local government charges its water customers.

Water Distribution

Getting water to the places where people can use it conveniently requires a network of pumps, tanks, and pipes. Treated water is pumped into elevated storage tanks so that it can flow through underground pipes to all the places it will be used. Keeping the water under pressure ensures that it will flow through the distribution system whenever a faucet or fire hydrant is opened. Each house, school, office building, store, or factory using water from the public water system is connected to the water distribution lines.

In addition to the costs of obtaining and treating water, another expense of a public water supply is the construction and maintenance of the pumps, tanks, and water lines. These costs are also included in setting the fee people pay a public utility for the water they use.

A meter at the point of connection measures how much water flows out of the line and into each customer’s property. These meters are read periodically, and the customer is billed for the water that has passed through the meter. Some water utilities use automatic meter reading technology that eliminates the need for physical meter reading.

Besides distributing water to users, the water lines provide another benefit. Fire hydrants connected to the lines give firefighters ready access to water to fight fires. Public water systems need to deliver enough water for firefighting, as well as enough for residential, commercial, and industrial uses.

Preventing Water Pollution

Liquid wastes from houses, schools, stores, offices, and factories are potentially dangerous. If they are not treated, these wastes can contaminate water with the chemicals or bacteria they carry. Similarly, rainwater can wash oil, fertilizers, and other chemicals from streets and roads, fields, lawns, and other outdoor locations into the sources of drinking water.

Many local governments operate sanitary sewers and sewage treatment plants to control water pollution from household, commercial, and industrial sewage. In areas where houses are far apart, household drains can go into septic tanks in which harmful bacteria are killed by natural processes. In these areas each house usually has its own septic tank. However, these cannot be used in densely populated areas or in areas where the soil will not readily absorb the water that has been treated in the tank. In these areas, wastewater is collected in sewers, which deliver it to a sewage treatment plant.

At the sewage treatment plant, chemical and biological processes eliminate bacteria from the wastewater and separate solids from the liquid wastes. The solid material separated from sewage is called sludge. Properly treated sludge is safe to use for fertilizer and is often recycled in that way. Properly treated water from sewage is safe to release into rivers or lakes and becomes a part of the water supply for residents farther downstream.

The costs of building and operating the sewage collection system of pipes and pumps and the sewage treatment plant are included in the sewage utility fee charged to customers. Typically, users pay for sewer services along with their regular water bill and the amount of the charge depends on the amount of water used.

To avoid contaminating water, hazardous chemicals, such as oil and many industrial and cleaning products, should not be poured down the drain where they might interfere with sewage treatment processes. Nor should oil and other harmful chemicals be poured on the ground where they can wash into streams and rivers. Storm water runoff picks up these and other harmful chemicals like fertilizers as it runs along the surface and into streams and rivers. These chemicals, as well as large amounts of human or animal waste, pollute the water and make it unsafe to drink.

Federal environmental protection regulations require local governments in densely populated areas to control storm water. Storm sewers and drainage systems can keep rainwater from entering the sanitary sewers and overflowing sewage treatment plants. Holding ponds that slow down the flow of runoff and allow the storm water to soak into the ground can filter the harmful chemicals out of storm water. Permanent borders of plants along stream banks also help catch pollutants before they wash into streams.

Building storm sewers and drainage systems, creating retention ponds, and protecting natural buffers along streams is expensive, so some local governments have created storm water utilities, in addition to their water and sewer utilities. Storm water fees are often based on the amount of paved ground or other hard surface area a property owner has, because water is much more likely to run off hard surfaces directly into streams, rather than soak into the ground. Storm water fees are often included in bills for water and sanitary sewer services.

Solid Waste Management

Everything people no longer want or need must go somewhere. Solid waste—old newspapers, food scraps, used packaging, grass clippings—must be disposed of safely. Chemicals from casually discarded trash can contaminate water. Garbage and trash also create a health hazard by providing a home for rats and other disease-bearing pests. Burning trash does not solve the problem of safe disposal because the smoke can pollute the air unless special incinerators are used.

Local governments help solve the problem of safe solid waste disposal in three ways.

- They support recycling.

- They help collect trash and garbage.

- They provide sanitary landfills or incinerators so that waste that cannot be recycled is safely buried or burned.

Safe (and low-cost) solid waste disposal depends on the cooperation of everyone in the community.

The least expensive way to deal with waste is simply not to create it in the first place. Reducing packaging and use of disposable items, for example, can reduce waste considerably. In many communities, people help reduce what governments pay for collecting recycling and solid waste by taking these materials to collection centers or by putting their recycling or trash collection bins at the curbside for collection.

Recycling

Recycling wastes means using them as a resource to make new products. For example, wastepaper can be recycled to make new paper and old glass bottles can become new bottles. Some recycling can be done at home. Leaves can be turned into mulch, fruit and vegetable peels into compost. Many people are not used to sorting their trash or reusing it at home, but that is changing. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), recycling rates have increased from just over 6 percent of municipal solid waste in 1960 to about 10 percent in 1980, to 16 percent in 1990, to about 29 percent in 2000, and to over 35 percent by 2017.

Local governments encourage recycling by urging people to separate materials that can be recycled and by telling people how they can reuse materials. In a materials recovery operation, workers sort through the solid wastes that have been collected and pick out things such as glass and cardboard. Then the remaining wastes can be passed through magnets to remove iron and through another process to remove aluminum. Separation at the source (by residents in their homes) is less expensive and is done in some communities, but it requires active participation to be effective.

Most larger municipalities and some counties have door-to-door recycling collections. Recycling collections are usually made on a different day and a different truck than solid waste collection. In communities where residents pre-sort their recyclables, the recycling truck has bins for different sorts of material. As the recycling crew empties the containers of recyclables left outside each house, they separate the different kinds of materials. Many other recycling programs are “single stream,” meaning residents do not sort different materials. They are collected together and sorted off site. Some local governments also operate recycling centers where people can deliver their recyclable materials.

Most of the manufacturing of new products from discarded materials is done by private industry. Paper companies use wastepaper to make new paper; glass companies use discarded bottles to make new bottles. Local governments that collect these recyclables sell them to the manufacturing companies. The money the governments receive from these sales helps pay for the cost of collecting the materials.

Recycling Challenges

A November 2019 report on recycling in North Carolina found that recycling operations here and across the United States were struggling with what to do with recyclable waste. Most U.S. recyclables had historically been purchased by overseas businesses, primarily in Asia, but those countries began to limit importation of raw recyclable materials. Further, the report said that not enough U.S. manufacturers were using recycled materials. Local governments have used the money they received for those materials to help pay their costs of collecting and sorting them. If no one buys recyclable materials, they wind up in a landfill. Some local government recycling programs have been discontinued or scaled back because of the weak market for the waste they collect through recycling.

As recycling becomes more expensive, local governments face the problem of what to do. Should they stop paying for recycling and send more waste directly to the landfill? Or can they encourage people to create less waste? What kinds of things could you do to reduce the amount of waste you produce?

Some cities and counties are making recycled products themselves. Many local governments have begun to use yard waste (grass clippings, leaves, chipped wood) to make compost or mulch. Local governments also support recycling by buying products made of recycled materials. By using recycled paper, for example, governments create a greater demand for old newspapers to sell to the companies that make recycled paper.

Governments support recycling to protect natural resources. Government officials also have a more direct interest in recycling: saving money. Burying trash in a sanitary landfill is very expensive. Burning solid wastes safely is even more expensive. Recycling can save money because it reduces the amount of material going into landfills.

Solid Waste Collection

Most cities and towns provide for house-to-house collection of solid waste. Once or twice a week, the “garbage truck” comes down each street and the crew empties the trash from the cans outside each house. Some cities have their own trucks and crews while others contract with private companies to collect solid waste. The truck, called a “packer,” is specially designed to crush the waste and press it together tightly so that it takes up as little space as possible.

In some municipalities, the city also collects solid waste from apartments, stores, and offices. Oftentimes, however, these non-single-family property owners are required by local government to hire private contractors to collect their solid waste.

Most counties and some small towns do not provide house-to-house solid waste collection. Instead, these residents either hire a private company to collect their trash, or they take it to a waste collection site themselves. Bins for recyclable materials are also often placed at waste collection sites. Most counties operate several waste collection sites. Sometimes the waste collection site consists of a large (usually green) box into which people put their trash. The box is emptied regularly into a very large packer truck. But if the box is not emptied often enough, or if people are not careful how they handle their trash, waste can spill out of the box. Green box sites can become very smelly trash-covered places and create health hazards.

An alternative is the supervised waste collection site. Supervised sites have a packer right on the site. The packer operator sees that people put their trash into the packer, which immediately crushes the trash. Both the supervision and the immediate packing of the waste help prevent the mess and hazard of green box sites.

Some dangerous materials require special handling. State and federal regulations prohibit radioactive wastes and hazardous chemicals from being mixed with other solid wastes. These materials (including motor oil, paints, other household chemicals, tires, and batteries) must be kept separate and cannot be collected through the regular collection system. People who discard them are responsible for sorting out these materials and making sure that they are collected appropriately.

Solid Waste Disposal

In North Carolina, each county is responsible for making sure solid wastes produced in the county are disposed of safely. Wastes can be buried or burned. Each of these disposal methods requires special equipment and techniques to assure public safety. Many counties operate their own landfills. Others hire private businesses or contract with another local government to dispose of their solid waste.

The most common way to dispose of solid waste is to bury it. Safe burial of wastes requires the construction and operation of a sanitary landfill. State and federal regulations set requirements for sanitary landfills to ensure that the landfill does not pollute the water or air. The landfill pit must be lined with plastic so that rainwater will not carry chemicals from the waste into the ground water. Any liquids or gases that do escape from a landfill must be captured and treated before being released. Each day’s waste must be covered with soil so that animals that might spread diseases are not attracted to the site. No fires are allowed. When the landfill is full, it must be covered with more soil, planted with grass or trees, and monitored to make sure that any leaking liquids or gases are properly treated. Landfill operators direct the unloading of waste and see that it is properly covered. They must be specially trained to ensure safe handling of the wastes.

The costs of the land, constructing the landfill, and operating it in accordance with state and federal regulations are considerable. Some counties decide not to operate a landfill or incinerator. In these cases, they either pay another county or a private company to dispose of the solid waste generated in the county or they help operate a regional (multi-county) landfill. In either case, these counties typically build transfer stations where waste collected in the county can be loaded onto very large trucks or railroad cars to be carried to a landfill in another county, or even another state.

The safe burning of wastes is even more expensive. This process is called incineration and requires very special equipment. First, materials that will not burn (glass, metal, and rock, for example) must be sorted out. Then the burnable materials must be shredded. Special furnaces are required to burn the waste at very high temperatures so that as many harmful chemicals as possible are destroyed by the fire. There is some smoke, however, even from a very hot, clean-burning fire. This smoke must be filtered and treated carefully to prevent air pollution.

To help pay the costs of solid waste disposal, many counties charge users tipping fees for the waste unloaded into the landfill, incinerator, or transfer station. Some cities and counties charge individual households or businesses for the costs of collecting and disposing their solid waste. The more waste they produce, the more they pay. Other local governments finance solid waste collection and disposal with taxes. The public can help keep these costs as low as possible by cutting down on what they throw away, by sorting out recyclable materials from the rest of the trash, and buying products made from recycled materials.

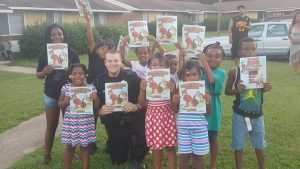

Parks and Recreation

Many local governments provide recreational opportunities for their residents. Municipalities and counties build and maintain parks, which may have picnic tables, swing sets, ball fields, basketball and tennis courts, swimming pools, or other facilities. They operate recreation programs, which may include organized sports leagues, supervised swimming, instruction in crafts or games, and physical fitness programs. Parks provide safe, attractive places for people to enjoy themselves and relax, and recreation programs extend opportunities for healthful exercise and relaxation.

Parks and recreation programs are staffed by people with many different specialties. A supervised swimming program, for example, requires a staff of qualified lifeguards. Not only must they know lifesaving techniques, but they must also know how to operate the pool’s filtering system and how and when to add chemicals to keep the water safe for swimming. They also need to know how to communicate well with pool users to ensure safe use of the pool.

Similarly, the recreation assistants who referee games, teach sports, or lead crafts sessions need to know not only the rules and techniques specific to that activity, but also how to communicate effectively and to treat everyone fairly. Park maintenance workers use a range of skills to keep parks safe and clean. Park and recreation directors need to know about all these operations and how to plan and coordinate them. Many directors have studied recreation administration in college.

Not all the people who help staff recreation programs are government employees. In many places, volunteers from the community coach sports teams, referee games, and teach people crafts in the public parks or recreation centers. Nonprofit organizations use public parks and recreation centers for their summer camps, after-school programs, or activities for the elderly.

Buying the land for a park, landscaping it, and building park facilities are major investments for local government.

Many city and county parks include playgrounds and basketball courts. Some have swimming pools, ball fields, golf courses, stadiums, or other large facilities. Large parks often have hiking trails and some local governments have built trails through greenways along streams or abandoned railroad lines. Many parks include picnic shelters and some have recreation centers.

Each park and recreation facility should be designed and built for public use. While a park or recreation center is a success only if people use it, overuse creates wear and tear. Thus, parks require constant maintenance. Lawns must be mowed. Equipment must be repaired and sometimes replaced.

Keeping a park clean and in good repair costs money. Vandalism—the purposeful destruction of property—creates an even greater need for maintenance. Often a city or county does not have enough money to repair or replace park equipment that is broken before it would normally wear out.

People contribute to the success of a park by using it and doing so in ways that do not destroy the facilities or others’ use and enjoyment of the park. Public cooperation is an essential part of every park and recreation program.

Public Safety

Local governments provide the first responders who protect people’s lives and property. Most communities have separate departments to deal with crime, fire, and medical emergency, the three most common threats to public safety. A few municipalities have departments that combine police, fire, and emergency medical services functions, but typically separate departments provide

- police protection (including sheriff’s and municipal police departments),

- fire protection, and

- emergency medical services (EMS).

All counties and some cities also have emergency management plans for dealing with large-scale disasters.

Public safety agencies can be reached through a special emergency telephone number, 9-1-1. Trained operators ask callers to describe the problem and its location. Tracking systems usually enable the operator to know the exact location of the caller. Based on the information the caller provides, the operator decides what to do. Each 911 call center has a set of rules for deciding which public safety units to dispatch under what circumstances.

When a crime is in progress, a suspect is still on the scene, a fire is reported, or a victim is injured or ill, the appropriate units are dispatched to respond immediately. The caller will usually be asked to stay on the line to inform responding police, firefighters, and/or paramedics about changes in the situation and help direct them to the location.

In smaller 911 call centers, the telephone operator who answers the call may also serve as dispatcher. In larger centers, the work is divided. Operators receive calls, get information from the caller, and then transfer the call to a dispatcher who coordinates the responding units. Sophisticated radio and electronic communications systems and well-trained personnel enable swift and effective responses to emergencies.

Police Protection

Local law enforcement officers are available to help every North Carolina resident. Most crime prevention and criminal investigation in North Carolina is done by local police departments and sheriff’s departments, even though crimes are defined by the state legislature. Local police also control traffic and investigate traffic accidents.

Except for some of the smallest towns, each municipality in the state has its own police department. Gaston County also has a police department, and Mecklenburg County gets police protection from the Charlotte police department. In the other 98 counties, sheriff’s deputies provide police protection in unincorporated areas of the county and in small towns without their own police department. Police officers and sheriff’s deputies have similar duties and authority. In this section, we will often refer to them collectively as “police.”

Police officers are required to go through specialized training. They study both criminal law (which defines illegal behavior) and constitutional law (which defines your rights). They learn how and when to use weapons and other self-defense measures and to de-escalate violent situations. They learn how to gather information and evidence.

Police officers also study ways to communicate clearly and to understand, respect, and deal with the differences among people. In fact, communicating with people and responding to their concerns for safety are essential parts of police work. Most police officers realize that they need the respect and trust of the public to do their jobs well. The people and the police must work together to have safe communities.

Crime prevention and traffic control are public services that benefit communities as a whole rather than individual users. Investigations of crimes and traffic accidents, however, typically help individual victims, as well as the broader community.

Investigation of a crime or traffic accident typically begins when the victim or a witness calls the police, usually through dialing 9-1-1.

If the situation requires immediate police action, a dispatcher will radio police to respond at once. The caller will usually be asked to stay on the line to inform responding officers about changes in the situation and help direct them to the location. If the situation is less urgent, the 911 operator will record information about the incident and police may respond later.

Responding officers will stop any additional injury from happening and will make sure that emergency medical services are provided. The police will interview the victim and witnesses about what happened and inspect the scene. They will also arrest any criminal suspects still at the scene.

After the responding officer interviews victims and witnesses and inspects the scene, he or she will write an incident report describing the accident or the crime and any suspects. Responding officers turn in their incident reports before they leave work each day. Their supervisors review these reports and decide which crimes should be investigated further. The most serious crimes are usually assigned to detectives who specialize in criminal investigation.

Police – Community Relations

Wherever anyone lives in the United States, there are local government law enforcement officers (LEOs) who work for municipal police departments or county sheriff’s offices. Their job is to enforce the laws and respond directly to people who request protection. In many communities, LEOs and the people they serve respect each other and work together to keep the community safe and secure. But for too many people across America, the relationship between LEOs and the community has been tense. Cases of excessive use of force by police have eroded public trust. For example, high-profile cases of police shootings of unarmed persons of color, other perceived racially motivated use of excessive force, and unequitable treatment in the justice system motivated the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement, focused on racial justice in law enforcement and the court system.

To rebuild community trust and support, many police and sheriff’s departments have enacted reforms such as requiring officers to wear body cameras and creating community (or civilian) review boards composed of residents to provide oversight. They have trained officers to respond by using tools other than force, helping people calm down and listen to each other. Community policing programs have put LEOs in neighborhoods where they can build personal relationships with residents. Neighborhood watch programs include residents who volunteer to help the police by monitoring neighborhood conditions and reporting suspicious activities.

But the fight for equal justice continues, and efforts to build trust within their communities are one of the key tasks of law enforcement leaders in cities and counties across North Carolina and the United States.

Criminal investigations seek to identify the person(s) suspected of the crime, to arrest the suspect, to gather evidence that can be used in court to convict the suspect, and to recover any stolen property.

Public cooperation is essential to effective criminal investigations. In the first place, police rely on victims and witnesses to report crimes. Unless people are willing to tell police about incidents that appear to involve a crime, most crimes will never come to police attention. Moreover, most suspects are identified from witness accounts. Much of the work of criminal investigation is interviewing victims and witnesses to obtain as complete an account of the incident as possible. People must be willing and able to tell police what they saw if police investigations are to be successful.

Fire Protection

Fire departments protect lives and property in several ways. In addition to fighting fires, firefighters are also often the first responders to accidents and medical emergencies. They help prevent fires by educating people about fire hazards and conducting fire inspections. They also investigate the causes of fires.

Many larger municipalities have fire departments staffed by city employees. In many smaller municipalities and in counties, local governments help fund volunteer fire departments. Alternatively, some volunteer fire departments receive funds from a special property tax set by the county commissioners and collected by the county for the volunteer department. Still other local governments contract with a nearby fire department to provide fire protection within their jurisdiction. Local governments are not required by law to provide fire protection, but most do.

Fires can occur at any time. Fire departments must always be prepared to respond. Fire departments often pay firefighters to work shifts of several days at a time. Although they are often staffed by volunteers, some volunteer fire department also hire full-time firefighters to have personnel at the fire station ready to respond immediately to a dispatch. Often, emergency calls answered by volunteers are many miles outside the area served by the volunteer department, making it difficult for volunteers to respond quickly.

Firefighting involves using specialized equipment and techniques. It can also be dangerous and requires strength, agility, and discipline. Both paid and volunteer firefighters need training to do the work. The State Fire and Rescue Commission establishes training standards for various firefighting specializations. Many departments augment these standards, as well.

The quality and availability of fire protection directly influences what people pay for fire insurance. The Public Protection Classification (PPCTM) is a rating of fire departments that the State Fire Marshal conducts for homeowner’s insurance companies to use in setting rates for fire insurance premiums. Fire protection is so important to insurance that both the State Fire Marshal and the State Fire and Rescue Commission are part of the North Carolina Department of Insurance.

Emergency Medical Response

People who suffer accidents or sudden illness may require emergency medical attention to survive and regain their health. State law requires all North Carolina counties to make emergency medical services (EMS) available to everyone in the county 24 hours a day. EMS personnel respond quickly to reports of medical emergencies. They evaluate injuries and symptoms and provide immediate, short-term care to those who need it. They operate ambulances to take patients to hospitals for additional medical evaluation and care.

County government responsibilities include arranging for at least one licensed EMS agency, ambulance service, and dispatching system to serve the county. The state Office of Emergency Medical Services oversees local EMS systems and licenses individual EMS agencies.

To qualify for an EMS license, an agency must have a licensed physician as its medical director and a staff of credentialed emergency medical technicians. Training standards indicate what skills each category of technician must have. The Office of Emergency Medical Services issues credentials based on the mastery of the required skills.

Most EMS agencies are county departments. Others are units of hospitals or independent nonprofit organizations, often called “rescue squads.” Some EMS personnel are volunteers, although most are paid because of the extent of training required for the work. Not all rescue squads are licensed as EMS agencies, however. Only those that meet state requirements qualify as EMS agencies.

Disaster Response

Natural or man-made disasters involve police, fire, and EMS cooperation, but also require even more complex systems and additional training. Every county in North Carolina has an emergency management director. If a disaster occurs, this person coordinates government and private responses to restore public safety. County and municipal departments of public works, public information, finance, public health, and social services may be involved, in addition to police, fire, and EMS. Private agencies—including hospitals, the Red Cross and other nonprofit organizations—as well as grocery stores, building supply stores, and other businesses may also participate.

Each county prepares an emergency management plan for approval by the state Division of Emergency Management. The plan lists potential disaster risks the county might face, the resources available to deal with each type of disaster, and the arrangements for coordinating the responses. The emergency management director oversees development of the plans with cooperation from representatives of the various agencies that may be involved in responding to a disaster. Through training exercises these partners test and refine the plan and experience working together. The partnerships for dealing with disasters also include mutual aid agreements with neighboring local governments and arrangements with state agencies.

In larger counties, the emergency management director is a full-time job, but in most counties, those duties are part of the work assigned to someone who has other responsibilities as well. Some cities and towns also have emergency management directors and develop their own plans for responding to disasters in their municipalities.

Social Services

North Carolina counties have important responsibilities for assisting people with low incomes and other social problems. County departments of social services help children through programs like foster care, adoption, and family counseling. They investigate suspected abuse of children and disabled adults. They offer services to help the elderly and the disabled live at home, as well as programs to help people prepare for new jobs. County departments of social services often work closely with religious and other charitable organizations in providing these services.

In providing some services, the county must follow very specific regulations. For example, counties administer the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (often called by the historical name of food stamps) and Medicaid (medical insurance for low-income families) in accordance with federal regulations. Counties must follow these regulations in determining who is eligible to receive assistance and in organizing and operating their departments of social services to carry out the programs because most of the funding for these programs comes from the U.S. government. To be eligible for these federal funds, states must have programs that meet federal requirements. Most of the 50 states use a department of state government to administer public assistance, but North Carolina is one of a few states that assign administrative responsibility to counties. Still, the state (which also pays part of the cost) must assure the U.S. government that federal requirements are being met. Strict regulation of county operations is one way to do this.

Another reason for strict regulation of public assistance programs is concern about welfare fraud. Many people believe that having very strict regulations will help ensure that only those who most need public assistance will receive these benefits. Others argue that too many regulations make it difficult for people to get the public assistance they need and that it drives up the cost for those who do receive benefits.

To provide greater flexibility in meeting people’s needs for financial assistance, North Carolina counties also operate Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) programs, called Work First. Under TANF, local departments of social services use federal, state, and local funds to provide support to families that do not earn enough money for basic living expenses. Work First can provide families money for a limited period while the parents find new jobs. Work First also provides job training and helps pay for childcare, transportation, or other services the parents may need to keep a job.

Many counties have also established their own general assistance programs. These optional programs help people deal with emergencies and situations not covered by federal and state programs. The county social services board establishes the rules for general assistance in its county, and the board of county commissioners allocates county funds to pay for general assistance.

Government programs do not cover all basic needs, however. Religious groups and other charitable organizations operate shelters for the homeless and for battered women, food banks and hot meals programs, clothing distribution centers, and other projects to meet the basic needs of those who cannot earn enough to provide for themselves. Some of these agencies also receive funding from county government to help them deliver specific social services. County social services departments often work closely with these nonprofit charitable organizations to assist people in need.

Health Services

County governments in North Carolina have important responsibilities for the health of the people in their communities. State government assigns most of these responsibilities and provides some of the funding for carrying them out. State laws separate these responsibilities into two broad categories:

- public health, and

- mental health, developmental disabilities, and substance abuse (MHDDSA).

Public Health

In North Carolina, local public health departments remove health hazards from the environment, educate people and give shots to prevent illness, and provide care for those who are physically ill and cannot afford to pay for care. The public health department may be organized for a single county or for two or more counties.

Each public health department must provide certain state-mandated services. It must inspect restaurants, hotels, and other public accommodations in the county to be sure that the facilities and the food are safe. It must also collect information and report to the state about births, deaths, and communicable diseases in the county.

COVID-19: How Local Public Health Departments Fight Disease

The COVID-19 (also known as coronavirus) global pandemic that made its way to United States shores in early 2020, highlights one of the important roles local public health departments play in their communities. They combat infectious disease by educating the public about diseases like the measles, tuberculosis, and seasonal flu. They provide immunizations to help prevent local outbreaks. In rare cases where a dangerous disease like tuberculosis or COVID -19 is reported, they use contact tracing to help contain it.

In contact tracing, public health workers track down persons that have been in close contact with an infected person to help them take precautions to avoid spreading the disease. Once someone tests positive for the disease, they are interviewed to find out where they have been and with who they have been in close contact. That information is then used to notify others who might have been infected through that contact. Those people are asked to get tested, quarantine at home, or take other steps to avoid community spread. Contact tracing work done by local public health departments is a critical component of worldwide efforts to reduce the spread of infectious diseases. Contact tracing helped eliminate the deadly disease of smallpox and greatly reduced the spread of other diseases like polio.

Local public health departments also typically provide many other services. They have programs to prevent animals, such as mosquitoes and rats, from spreading human diseases. Many public health departments also enforce local sanitation ordinances for septic tanks or swimming pools and local animal-control ordinances. County nurses and health educators teach people about good nutrition and how to prevent illness. Most public health departments operate clinics to diagnose and treat illnesses and to provide health care for expectant mothers, infants, and children who cannot otherwise afford health care. County nurses also care for people in their homes and at school and they also give shots to prevent certain diseases.

Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Abuse (MHDDSA)

County government’s role in MHDDSA is to establish, jointly with one or more other counties, a local management entity (LME) responsible for delivering publicly funded, community-based MHDDSA services in the county.

State and federal governments provide much of the funding for community-based treatment of mental illnesses, mental disabilities, and the abuse of alcohol and other drugs. However, counties must appropriate funds as well, although not at any particular level. State policy requires LMEs to develop a network of service providers who deliver services directly to clients. These service providers may be public or private entities. The LME role is to authorize the expenditure of public funds for services to qualifying individuals and to monitor the cost, quality, and effectiveness of these services for individual clients.

Public Schools

In North Carolina, public schools are both a state and a local responsibility. The state pays teachers’ basic salaries and establishes qualifications for teachers. Teachers are considered state employees. The state does not hire teachers, however. Teachers are hired by local school boards, and local school boards are also responsible for deciding to retain or dismiss teachers.

The North Carolina State Board of Education establishes overall policies for the schools, including the minimum length of the school year, the content of the curriculum, and the textbooks that may be used. Local boards of education must meet the state’s guidelines for school policy when making decisions about how the local schools will operate. Local school boards hire all local school personnel: teachers, staff, and administrators, including principals, superintendents, and their assistants. Local school boards decide what texts to use and what courses to offer. They set the calendar for the local schools and decide on school attendance policies.

Local school boards also adopt a budget for operating the schools. Teachers’ basic salaries and some of the costs for school buses are paid by the state. Money for school lunches and support for some educational programs comes from the federal government. Most other costs of the schools are a local responsibility. These include funds for buildings, furniture, equipment, books and other supplies, maintenance, and utilities. Many local school systems also pay teachers a salary bonus. The local school board decides how much money it needs to support the local schools. Then it presents this budget to the board of county commissioners. The school board has no authority to tax.

Most counties have a single local school system (“local school administrative unit”), although a few counties still have more than one. Each local school system has its own elected board.

In many counties there are also public charter schools. These schools receive a share of the state and local funding for public school instruction. Charter schools do not receive government funding for building construction and maintenance, school lunches, or school buses. They have their own governing boards and operate somewhat independently of state and local polices for public schools. They are open to students through a lottery and most often enrollment is not connected to county of residence as it is in traditional public schools.

The county commissioners decide how much county money to spend to support local schools. In most counties, schools receive the largest share of county money. Sometimes there is considerable discussion between the school board and the commissioners about how much money the schools should receive.

Each local school board hires a superintendent to coordinate planning for the schools, select teachers and other school staff, prepare and administer the budget, and provide general administrative direction for the schools. Each school has a principal who has similar responsibilities for that school. In many parts of the state, schools are also beginning to involve teachers and parents more directly in helping plan for the school and in making decisions about how the school is run. Some schools also have advisory committees of people from local businesses and other members of the community.

Public schools have the responsibility of helping their students prepare for life. Some public-school programs help prepare students directly for work. Other programs help students prepare for college. All public-school programs should help make students responsible citizens—people who take pride in their community and help make it a better place to live and work.

Municipal Streets

Providing for safe and efficient traffic flow in cities and towns involves both state and local governments. Most streets inside municipal boundaries are the responsibility of the municipal government. However, the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) has responsibility for most thoroughfares that pass through cities and towns. Many major streets, as well as interstate and state highways inside city limits, are built, maintained, and regulated by state government.

So while city officials have sole responsibility for most streets, they must work with NCDOT on changes to many of the key streets that carry heavy traffic. Cities and towns can build new streets. They can widen, repair, or repave only those streets that are not part of the state system. They can install speed bumps, lane markings, traffic signs, and traffic lights on city-maintained streets but not on state-maintained streets. City officials must ask NCDOT to make changes on any street that is part of the state highway system.

Cities can build and maintain sidewalks and street lighting on both city-maintained and state-maintained streets within their boundaries.

New streets are needed when land is developed. Often municipalities require the company developing the land to build streets to provide access to the new buildings. They often specify that these streets must meet the same design and construction standards the city would use if it were building the streets to ensure that the streets will be durable, safe, and convenient. Often new sidewalks and streetlights are required as a part of new construction. In some cases, cities take ownership of the new streets, sidewalks, and streetlights, but in other cases ownership and responsibility remains with the business or for residential neighborhoods, the homeowners' association created by the developer.

Both municipal and county governments advise NCDOT on highway construction in metropolitan areas. Each of the state’s urban areas with a population of 50,000 or more has a metropolitan transportation planning organization (MPO). Through each MPO’s Transportation Advisory Committee, elected officials from the municipalities and counties in an area plan changes in the state highway system in their area. These plans include both new construction and repair priorities for NCDOT’s consideration.

Streets should make safe and convenient travel possible. They need to be wide enough to handle the traffic they carry. Sometimes this means having multiple, well-marked lanes (including bicycle lanes in some places).

Safety also requires that streets not have potholes, standing water, or other hazards that might cause drivers to lose control of their vehicles. Busy intersections need traffic signs or signals to prevent collisions. Street signs provide directions to drivers. Municipal public works or street departments carry out city policies to make streets safe and convenient.

Street cleaning also contributes to the safety of travel, as well as to the cleanliness of the city. Removing debris from streets, operating mechanical street sweepers, and plowing snow from the streets are other responsibilities of city public works or street departments.

Sidewalks help keep pedestrians safe by separating them from traffic and providing a smooth walking surface. They also make it convenient to walk, rather than drive, for short trips. Streetlights also contribute to the safety and convenience of both drivers and walkers.

Each city’s network of streets and sidewalks is a public service used directly by all those who go from place to place within the city. All drivers pay a special tax on gasoline and diesel fuel they buy. A part of this state motor fuels tax goes to municipalities for the construction, maintenance, and cleaning of city streets. These “Powell Bill” funds cover much of the cost of these city services.

Rural public roads in North Carolina are all part of the state highway system. Unlike many states, North Carolina has no roads maintained by county government. As of 2019, NCDOT maintains over 107,000 miles of roads and North Carolina municipalities maintain over 23,000 miles of streets and roads.

Take Action

✔ If your home receives public water, find out more about your local water system. What is the water source? Where is the treatment plant located?

✔ Find the latest water quality report for your water system. If you are on a well, what do you know about the quality of the water coming from your tap?

✔ Find out which watershed you live in and learn more about the volunteer watershed group that works to help improve the health of the watershed (see http://ncwatershednetwork.org). See what volunteer opportunities exist.

✔ Learn more about how the community you live in manages stormwater. Where does stormwater go in your community?

✔ Find out more about recycling in your community. What can you do to reduce the amount of trash that goes to landfills?

✔ Visit your local parks and recreation department. What recreational opportunities are provided by your local government? Are there opportunities for you to get involved in some way?

✔ Learn more about your local law enforcement. Is there a citizens’ police academy that you could attend? Are there “ride-along” opportunities for residents? Are there community policing programs in your area?

✔ Where is the nearest fire station? Is it a volunteer fire department or a city department?

✔ Find out more about your local social services and public health departments. Are there opportunities for volunteer service?

✔ Learn how you can help inform your city about street repairs that need to be made. Is there an easy way to report problems? Some local governments have smartphone apps where you can take a picture of a problem and send it to the public works department so they know a repair is needed. Does your local government utilize a reporting system like that?

government purchase of a service from a business instead of producing the service itself

an organization (such as a city or county department or private provider) that builds, maintains, and operates infrastructure (and its associated system) for public services like gas, electricity, water, and sewage

water that collects underground

the process by which the salt is taken out of water

all waters on the surface of the Earth found in rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, and so on

an area that drains water into a stream or lake

(also known as public authority) unit of local government created by the General Assembly to deliver a specific service, usually with territorial boundaries larger than a single jurisdiction and often encompassing several jurisdictions

a material that pollutes

anything that harms the quality of air, water, or other materials it mixes with

efforts to reduce runoff of rainwater or melted snow into streets, yards, and other locations in order to protect or improve water quality; an important environmental service of many local governments that contributes to community well being

a container in which wastes are broken down by bacteria

the solid material separated from sewage

material spread around plants that prevents the growth of weeds and protects the soil from drying out

decayed material that is used as fertilizer

an area in which is located a large receptacle for trash, usually painted green, that often emits a foul odor if solid waste is not regularly collected

a site built into or on top of the ground in which trash is stored for permanent disposal and isolated from the surrounding environment (groundwater, air, rain); also known as sanitary landfill

the safe burning of wastes

a charge imposed on a user based on how much solid waste they bring for disposal at a landfill

a person who gives emergency workers information so that those workers can respond to emergencies

a report that a police officer writes describing a crime or other problem situation

commitment by local governments to assist each other in times of need

a program to help people with financial need buy food; vouchers to be used like money for purchasing food; federal program, but administered by county departments of social services in North Carolina

a program designed to pay for medical care for people in financial need; federal program, but administered by county departments of social services in North Carolina

federal government program of support for families in need but administered by counties in North Carolina; provides small payments to cover basic living expenses and assistance to help adults find and keep jobs

a group of residential properties organized into a neighborhood by a real estate developer and maintained as a private, nonprofit corporation

a North Carolina state law that allocates part of the state’s gasoline tax to municipal governments to build and repair city streets