Protecting the Public from Harm

Learning Objectives

- Understand how local governments regulate behavior through ordinances

- Consider how zoning laws shape your community

- Understand and appreciate civic responsibility and your public participation options

One of the most powerful tools local governments use to improve their communities is the authority to regulate harmful behavior within their jurisdictions. North Carolina state law gives counties and municipalities authority to regulate various activities to protect people from harm. For example, local governments can pass “leash laws” requiring owners to control their dogs, thereby reducing the danger of people being bitten. Local governments can adopt building restrictions to prevent people from constructing buildings in areas that are likely to be flooded. City governments can set speed limits and other regulations for traffic on city streets.

To regulate behavior, the local governing board must adopt an ordinance—a legal description by the board of the behavior being regulated and the actions the government will take against people who do not follow the regulation. Where state law does not already permit local government regulation of an activity, local officials must ask the General Assembly to pass a bill granting that authority.

People often disagree about whether a given activity is harmful enough to require regulation. Local governing boards often seek public comments and suggestions before passing ordinances. They may hold public hearings to encourage full discussion of the arguments for and against a proposal to regulate. Sometimes an advisory board or a committee of residents also reviews the arguments about a proposed regulation and presents these to the governing board. Residents also often speak directly to board members about proposed regulations they favor or oppose. But the decision to regulate must be made by the local governing board. Unless a majority of the board thinks regulation is appropriate, no action will be taken. Except for a few cities (such as Greensboro, N.C.) that have initiative and referendum provisions in their charters, an ordinance can be adopted only by the board.

Government regulation involves requiring or prohibiting certain actions. If someone fails to act according to the requirements of the ordinance, the government can either refuse them specified public services or impose penalties on them. The ordinance specifies what service may be withheld or what penalties may be imposed. Some regulations are enforced by withholding public services until the person acts as the regulation requires. For example, a person who wants to connect his or her home to the public water supply must get permission from the water department. To protect the water supply, local regulations specify the kind of plumbing the owner must install. Then, before the water department turns on the water, an inspector checks the plumbing to be sure it meets specifications.

People who violate an ordinance often must pay a civil penalty of a specified amount of money. When an official enforcing the ordinance determines that a violation has occurred, the official issues a citation to the violator, assessing the civil penalty. Sometimes there are other penalties, too. For example, the ordinance regulating parking may include a provision for towing cars parked in parking places reserved for the disabled. Violations of some ordinances may also carry a fine or time in the county jail. People charged with violating these ordinances have a hearing at which a magistrate or district court judge determines whether they are guilty of the violation and, if so, what their sentence will be.

Police officers are given responsibility for enforcing many local ordinances, but other local officials are also responsible for enforcing specific ordinances. These include building inspectors and zoning inspectors. Often these same local officials are also responsible for enforcing state laws and regulations. Local police enforce North Carolina’s criminal laws, as well as local ordinances. Local building inspectors enforce the state building code in addition to any local building ordinances. Local ordinances must not conflict with state laws and regulations.

Many regulations require popular support to achieve their purposes. For example, most people must cooperate with restrictions on smoking in public places or requirements to keep dogs under control in order for these ordinances to be effective. Police enforcement can help make people aware of the law, but the police cannot be everywhere at once and cannot deal with widespread violations. Fortunately, most people see the need to regulate some behaviors and accept their civic responsibility to obey laws, even when they disagree with them. This is the basis for the success of most government regulations.

Regulating Personal Behavior

Governments regulate personal behavior that threatens people’s ability to live and work together in safety and security. Much harmful behavior is regulated by laws passed by the North Carolina General Assembly. For example, state laws declare certain acts to be crimes. Crimes are offenses against all the people of North Carolina, not just the victim who is harmed directly by the act. State laws also provide rules for the safe operation of cars and trucks on the state’s highways. State laws apply to the entire state. Similarly, Congress passes laws regulating behavior throughout the entire nation.

Local governments also regulate disruptive behavior within their jurisdictions and adopt ordinances setting up rules for the use of parks or other facilities open to the public. Local government regulations must not violate either the state or federal constitution, and local governments must have authority for their regulations from the state of North Carolina. Local governments in North Carolina have broad authority to regulate behavior that creates a public nuisance or threatens public health, safety, or welfare. Other kinds of local regulation require special acts of authorization by the General Assembly.

Cities and towns regulate traffic on their streets. For major thoroughfares (streets that carry traffic into and out of the city) the city or town shares this authority with the state. A city council can decide to put up stop signs or traffic signals or to set speed limits on most city streets, but for major thoroughfares, the council must request state action. Because rural public roads are the state’s responsibility, county governments must ask for state action to control traffic in unincorporated areas.

How Changing Views about Smoking Led to Regulation of Smoking

One example of how local ordinances change over time involves the controversy over regulation of smoking in public places. Historically, smoking was not viewed as a public problem. In fact, at one time the use of tobacco was considered by some North Carolinians as an almost patriotic duty. Tobacco was North Carolina’s chief crop. Much of the state’s economy depended on raising tobacco, selling it, and making cigarettes and other tobacco products.

This traditional view began to be challenged as medical researchers linked tobacco smoke to cancer, heart disease, and breathing disorders. Studies showed that breathing others’ second-hand smoke could harm nonsmokers’ health. This research increased the conviction among many people that smoking should be prohibited in public places. And now that significantly fewer people in the United States smoke, tobacco has also become a smaller part of the state’s economy.

In June 1988, Greensboro resident Lori Faley presented a petition to the Greensboro City Council to regulate smoking in public places. Ms. Faley started the petition after someone blew smoke in her face while she stood in a supermarket checkout lane. The petition she brought to the city council had more than 500 signatures and called for an ordinance regulating smoking in stores and restaurants, as well as in publicly owned buildings.

There was immediate opposition to the ordinance, especially from Greensboro tobacco companies and workers. More than 2,300 people were employed in the tobacco industry there at that time. The city council held a public hearing and then appointed a committee to study the issue. The committee was made up of representatives from the council, the county commission, and the county health department and business owners and managers. The committee held its first meeting in July 1989.

Ms. Faley and her group, which became known as GASP (Greensboro against Smoking Pollution), were frustrated at the council’s response and did not wait for the study committee to meet. GASP began to collect signatures on another petition. This petition took advantage of a provision in the Greensboro Charter for procedures called initiative and referendum. (Greensboro is one of only a few North Carolina cities with these provisions.)

The GASP petition called for the council to vote on the ordinance regulating smoking in public places. It also called for a referendum (public vote) on the ordinance if the council failed to adopt it. The initiative petition required the valid signatures of 7,247 Greensboro voters to force a referendum.

In August 1989, GASP submitted its petition. Although more than 10,000 people had signed the petition, only 7,306 signatures were certified as those of registered Greensboro voters. That was still more than the number necessary to require a vote. So after the city council refused to adopt the ordinance, the referendum was placed on the ballot for the November election.

Greensboro tobacco companies spent tens of thousands of dollars urging voters to defeat the ordinance. GASP did not have similar financial resources, but the group did have the names of those who had signed the petition. GASP members called those people to urge them to vote for the ordinance. The ordinance passed by a very narrow margin: 14,991 votes for and 14,818 against.

The controversy, however, did not end there. Tobacco workers in Greensboro started an initiative petition of their own. This time, the petition called for a referendum to repeal the smoking regulation ordinance adopted in 1989. The petitioners collected the required number of signatures, and another election was held in 1991. In that election, voters rejected repealing the ordinance by more than two to one. Although thousands of people in Greensboro were still unhappy with the city’s regulation of smoking in public places, Greensboro voters overwhelmingly supported keeping the ordinance.

Regulation of smoking in public places has become much less controversial. In 2007, the North Carolina General Assembly banned smoking in all state-owned buildings, effective January 1, 2008. By 2020, most local governments had banned smoking in their buildings and in restaurants, stores, and other public places.

Behavior that is acceptable in one community may be regulated as a nuisance in another community. For example, while some local governments have ordinances that require dog owners to keep their dogs penned or on a leash, some do not. Some cities and towns have ordinances regulating the loudness and/or the time of noisy behavior in residential areas. Views about the seriousness of the harm caused by an activity often vary from place to place across North Carolina.

Views about the harmfulness of an activity also change over time. For example, many cities and towns in North Carolina used to require stores to be closed all day on Sunday. Over the past 50 years, most of those ordinances have been repealed. In many parts of the state, more people wanted to shop on Sunday, and more merchants wanted to sell on Sunday. Fewer people believed it was wrong to conduct business on Sunday (or, even if they believed it was wrong, that the government should keep others from shopping on Sunday).

Regulating the use of property

Local governments regulate the use of property to protect people’s health and safety, the environment, and property values, as well as to encourage economic development. Several different kinds of property regulations are commonly used. Through zoning ordinances local governments specify the kinds of uses allowed in various geographic divisions of their jurisdiction. Subdivision regulation guides how large blocks of land can be developed for new houses. These are usually based on a land use plan.

Other local regulations also help protect the physical environment or community appearance. Local housing codes establish basic requirements for a structure to be adequate for someone’s permanent residence. Typical requirements include structural soundness (to prevent the collapse of walls or floors), adequate ventilation (to provide the occupants with fresh air), and a safe water supply and toilet facilities (to prevent the spread of disease). If an inspector finds that a building does not meet minimum standards, the inspector can order it to be repaired or closed. A local governing board can adopt an ordinance ordering that a building that is beyond repair be demolished. Most of North Carolina’s larger cities and counties have minimum housing codes.

Local inspectors also enforce the state building code to protect against unsafe construction. As building proceeds, inspectors check to see that construction meets legal requirements. Building codes set standards for safe construction, including plumbing and electrical systems. Inspectors also check to make sure the zoning requirements are being followed. Before the new building can be occupied, inspectors must certify that it meets all state and local requirements, including the zoning regulations. An occupancy permit is then issued.

Local governments may regulate activities that cause soil erosion or regulate building in flood plains or in reservoir watersheds. Local governments can prohibit signs they decide are too large or disturbing. They can regulate changes to the outside appearance of buildings in historic districts.

Land Use Plans

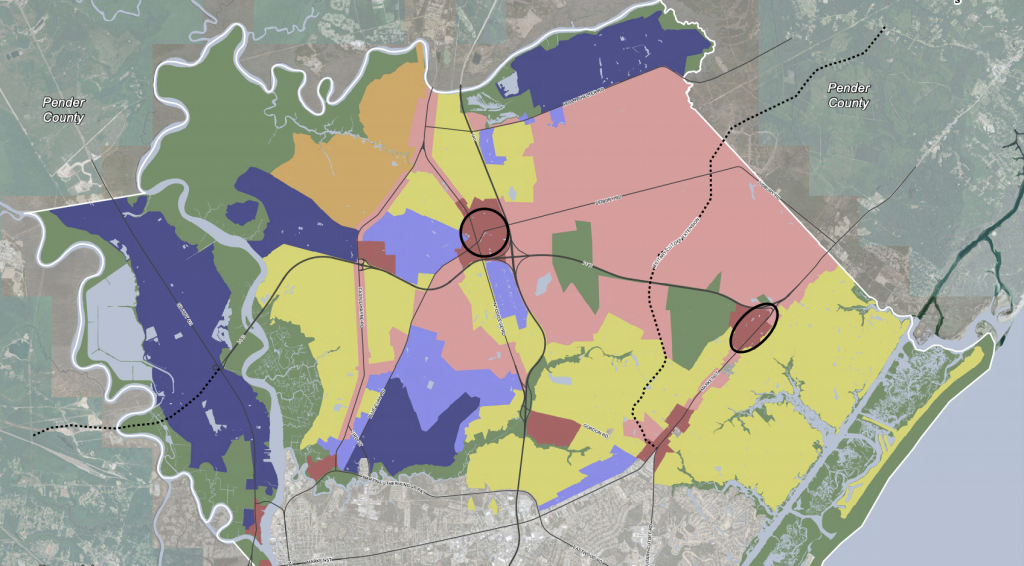

In many jurisdictions, a land use plan serves as the basis for much of the regulation of property use. City or county planners (or outside consultants) study the physical characteristics of the land. Where are the steep slopes? What areas are subject to flooding? They map existing streets, rail lines, water lines, sewers, schools, parks, fire stations, and other facilities that can support development. They also note current uses of the land. Where are the factories, the warehouses, the stores and offices, the residential neighborhoods?

Based on their studies, the planners prepare maps showing how various areas might be developed to make use of existing public facilities and to avoid mixing incompatible uses (keeping factories and junkyards separate from houses, for instance). The maps may also indicate where new water lines and sewers might be built most easily. These maps are then presented to the public for comment. After the public has reviewed the maps, the planners prepare a detailed set of maps showing current and possible future uses of the land. The local governing board may review and vote on this final set of maps itself or delegate planning authority to an appointed planning board. The approved maps and supporting text outlining future growth and development becomes the official land use plan for the community, usually called a comprehensive plan.

All except the smallest North Carolina cities and towns have land use plans. Municipal land use plans typically cover an area one mile beyond the municipal boundaries. The area outside the city limits, but under the city’s planning authority, is called the extraterritorial land use planning jurisdiction (ETJ). With the approval of the county commissioners, a city may extend its ETJ even farther.

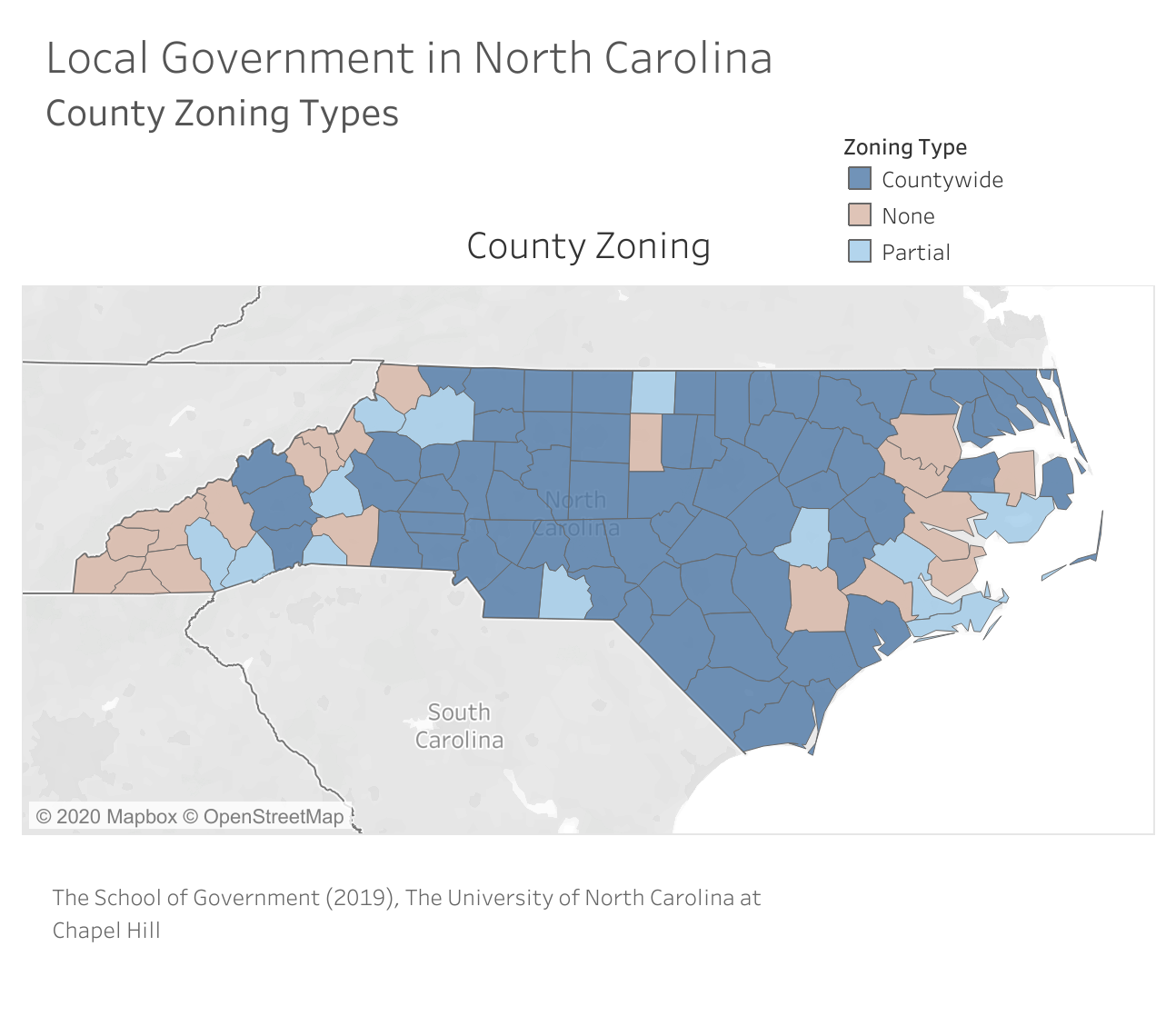

Counties are authorized to regulate land use only over the parts of the county not subject to city planning. Because of cities’ ETJ, a county’s land use planning area is usually smaller than the unincorporated area of the county. All but a few rural counties in North Carolina have land use plans. The twenty coastal counties and municipalities are also subject to land use regulations imposed by North Carolina’s Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA).

Local officials can use land use plans to guide their decisions about where to locate new public facilities—new parks, schools, or other government buildings. Some governments use them only for these nonregulatory purposes. A land use plan also establishes a basis for regulation of property uses. However, the plan itself does not set up a system of regulation. Zoning and subdivision regulation are systems of regulation based on a land use plan. A bill passed by the General Assembly in 2019 requires all North Carolina local governments that use zoning to have a land use plan by 2022.

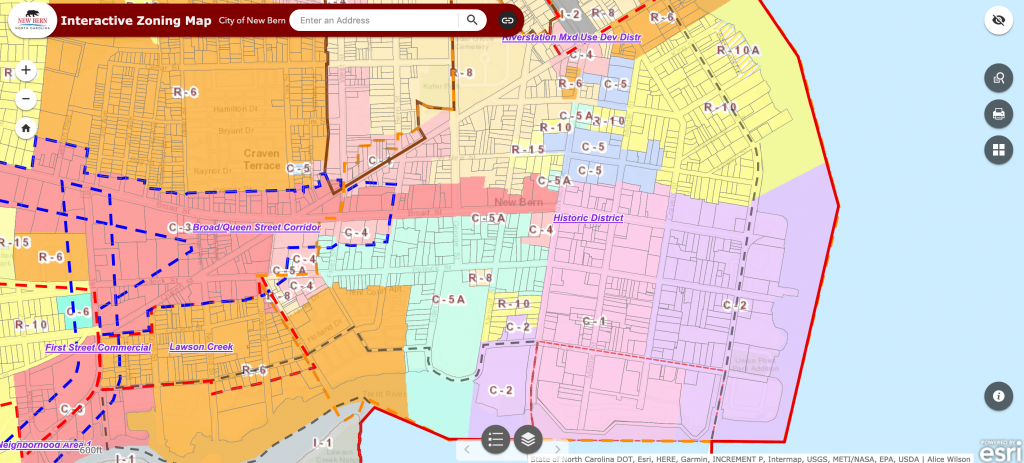

Zoning

Zoning involves dividing up the land within a jurisdiction into zones that spell out land uses that are permitted and prohibited within those zones. The local governing board establishes categories of land use. Then the categories are applied to specific areas of the jurisdiction, creating zones for different kinds of purposes. The categories specify the kinds of activities the land can and cannot be used for and various requirements for developing and using the land. For example, one residential category may be for single-family homes. That category might prohibit apartments, office buildings, or industrial plants within the zone. It might also require each lot to have a minimum size and that buildings be constructed a specified distance from the boundaries of the lot and under a maximum building height. Another zoning category could be commercial. It might prohibit industrial activity within the zone and require a certain number of parking spaces be provided for every 1,000 square feet of commercial floor space built. Another zone may allow mixed-use developments such as apartments, offices, and low-intensity business together in the same area.

To develop property that has been zoned, a developer must obtain a zoning certificate from the planning department. The planning department staff checks the building plans for the property to see that all zoning requirements are met. The department then issues a zoning certificate. The building department can then issue a building permit to allow construction to begin if the building plans conform to local and state building codes.

Zoning vs. Affordable Housing?

Regulating land-use is one of the most important powers local governments exercise. Decisions about the regulation of land use can also be controversial. For example, the Raleigh City Council created a “Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District” for the North Ridge West neighborhood to support residents’ desire to protect the character of the well-established neighborhood. Although one council member noted that it went against the city’s stated commitment to creating more affordable housing, the council approved the overlay district which was supported by neighborhood residents.

Overlay districts are additional layers of regulation on top of an overall zoning ordinance intended to preserve the unique characteristics of a specific neighborhood. The overlay district for North Ridge West placed restrictions on the types of homes that could built and cut the number of new homes that can be constructed in half.

Thus, the zoning decision met one local priority (preserving a neighborhood’s character) while limiting another citywide priority (addressing affordable housing). Zoning issues often involve this kind of tension between the needs of specific neighborhoods versus the needs of the community at large. How local government boards manage that tension can impact the character and dynamic of communities for decades to come.

Zoning applies to both existing and new uses of property. An existing store in an area zoned residential would not be forced to close if it was constructed before the zoning took effect; it would be considered a legal, nonconforming use. However, expanding the store or changing its use to a factory might be prohibited by the zoning ordinance.

Minor exceptions to zoning regulations can be approved by a board of adjustment. This board is made up of resident volunteers appointed by the local governing board. Boards of adjustment for cities with extraterritorial planning jurisdictions must include representatives from that area. The board of adjustment hears appeals about the decisions of the planning staff. It also hears requests for exceptions to the zoning regulations, called variances. Board of adjustment decisions usually cannot be appealed to the local governing board. Instead, appeals are made to the courts. This procedure is intended to keep political pressures from influencing land use decisions.

Major land use and zoning decisions can affect property values, traffic, noise levels, and many other aspects of life in a community, often making them controversial. To ensure opportunities for public input, all zoning change requests require public hearings. Also, major developments such as shopping centers require “special-use permits,” which can be granted only after a formal public hearing on the project.

All of North Carolina’s larger cities and towns have zoning regulations that the city council has adopted by ordinance. A municipality’s zoning authority also covers the extraterritorial planning jurisdiction, as well as the area within the municipality. Eighty percent of counties also have zoning for at least some of their area not under municipal jurisdiction. Most of the areas of North Carolina that are not covered by zoning regulations are rural and primarily agricultural, although popular resistance to having local government regulate land use has also prevented the adoption of zoning in a few more densely populated counties.

Subdivision Regulation

Subdivision regulation establishes a process for reviewing a landowner’s request to divide a piece of land into building lots. With subdivision regulation, the local government will not approve dividing land into lots for houses until the landowner satisfies certain conditions. These conditions typically include building adequate streets and providing appropriate drainage. The conditions might also include laying water and sewer lines if the new development is to be served by public water supply and sewers. In addition, each lot must be checked to see that it includes a safe building site. The landowner may also be asked to donate land for a park or greenspace. If the local government has established subdivision regulation, the register of deeds cannot record the boundaries of the new lots without approval of the local government. This assures that all regulations are followed.

Protecting North Carolina’s

Coastal Communities

Hurricane Florence, which slammed into North Carolina’s coast in 2018, damaged an estimated 75,000 homes and other buildings in the state, mostly due to flooding. Rising sea levels increase the likelihood of flood damage all along the coast. Land use plans and zoning can minimize flood damage by shaping choices about where and how to build. North Carolina’s coastline is made up mostly of small local governments that lack the resources to develop and implement the kinds of land use plans that would make the most difference. The state helps through its Office of Recovery and Resiliency (NCORR) and the North Carolina Sea Grant program.

Swansboro, in Onslow County, received assistance from N.C. Sea Grant to conduct a vulnerability assessment as it was updating its land use plan. The plan identifies flood-prone areas and requires rebuilding flooded buildings much higher than they were before. The Swansboro town plan also specifies that flood risk be considered in making decisions about building streets and water or sewer lines. Swansboro public officials and residents now know ways to minimize future flood damage.

Subdivision regulation is intended to prevent developments on land that cannot support them. For example, some land may be prone to flooding. Some properties may not have access to sewer lines and have soil unsuitable for septic tanks. Subdivision regulation ensures adequate street access and drainage are provided by the developer, so that residents (or the local government) are not left with the expense of building adequate roads or drains. Because many of these problems developed in earlier unregulated subdivisions, subdivision regulation is being used more and more. Rural counties where little development is occurring are least likely to have subdivision regulation.

Take Action

✔ Look up the local ordinances for your county and/or town, usually called the county or municipal code. Does anything surprise you in terms of ordinances that exist or ones you think should exist but do not?

✔ See if your county has an interactive GIS website, and if it does, look up the property where you live and see what information you can find out about it.

✔ Find the land use plan for your county and/or municipality. When was it adopted? When was it last amended? What does it tell you about future land use in your community?

✔ Find out when your local planning board or board of adjustment meetings are held and attend one. What kinds of issues do these boards deal with? What kind of information is used to help the board make decisions?

a group of residents appointed to provide oversight and advice to a department or to consider a project or issue (also known as an advisory committee or commission)

a way in which the citizens propose laws by gathering voter signatures on a petition; only a few cities and no counties in North Carolina have provisions for initiatives

a way for citizens to vote on state or local government decisions; an election in which citizens vote directly on a public policy question

fine or other financial penalty imposed by courts as restitution for being found guilty of a violation of law

an official summons to appear before a court to answer a charge of violating a government regulation

responsibilities or obligations association with being a citizen, such as voting and obeying laws

an act that is forbidden by law; an offense against all of the people of the state, not just the victim of the act

rules designating different areas of land for different uses

a document created to guide future land use decisions in a community, including a long-term vision and goals and guidelines for future development and other public investments (also known as a comprehensive plan)

the area outside city limits over which a city has authority for planning and regulating use of the land (often abbreviated as ETJ)

quasi-judicial body that hears requests for exceptions to zoning ordinance

permission to do something different from what is allowed by current regulations

a meeting designed for government officials to receive public comment on a specific issue before decisions are made; in some cases, such as passing a budget, a public hearing is legally required

rules for dividing land for development

public area with grass, trees, or other vegetation set apart for recreational purposes, or simply to beautify the community, in otherwise urbanized areas.

a person or business that builds houses or prepares land for building