Paying for Local Government

Learning Objectives

- Understand how the North Carolina Local Government Commission oversees municipal and county finances

- Describe the revenue streams for local governments

- Discuss different expenditures local governments make

- Consider how local government budgets shape your community

Local government services and programs cost money. Cities and counties must pay the people who work for them and provide the buildings, equipment, and supplies for conducting the public’s business.

In North Carolina, local government services and programs cost billions of dollars each year. In fiscal year 2018, North Carolina county governments spent almost $15 billion, and North Carolina municipalities spent about $11.2 billion, to provide services for the people of North Carolina. Within limits set by the state, local officials are responsible for deciding what to spend for local government and how to raise the money to cover those expenses.

The State of North Carolina sets strict requirements that local governments must follow in managing their money. However, this was not always so. During the 1920s, many cities and counties in the state borrowed money heavily. When the stock market crashed in 1929 and thousands of people lost their jobs, many local governments went even more heavily into debt. By 1931 the state’s local governments were spending half of their property tax revenue each year on debt payments. More than half of the state’s cities and counties were unable to pay their debts at some time during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

To restore sound money management to local government, the General Assembly created the North Carolina Local Government Commission and passed a series of laws regulating local government budgeting and finance. The Local Government Commission enforces those laws and, along with the School of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, provides training and advice to local government budget and finance officers.

State regulation provides a strong framework for sound money management, but local officials still have primary responsibility for using city and county funds wisely and well. Each year they must adopt a balanced budget for the coming fiscal year. During the past 70 years, North Carolina local governments have established a national reputation for managing public money carefully and providing the public with good value for their tax dollars.

At the end of each fiscal year, every local government in North Carolina prepares an annual financial report. This document summarizes all the government’s financial activity: what it has received, what it has borrowed, what it has spent, what it is obligated to spend, and what it has in the fund balance. Each local government publishes its annual financial report, has it audited by an independent accounting firm, and files a financial summary with the Local Government Commission.

The report helps local officials better understand the financial situation of their government. The independent audit and the report to the Local Government Commission serve as checks on the accuracy of the report and the legality of the government’s financial dealings. The publication of the report also informs citizens about their local government’s financial condition.

Local Government Budgets

A budget is a plan for raising and spending money. North Carolina law requires each city and county to adopt an annual budget every year, including planned revenues and expenditures for the coming year.

In North Carolina, local government budgets must be balanced. That is, the budget must indicate that the local government will have enough money during the year to pay for all planned expenditures. Expenditures can be paid either from money received during the year (revenue) or from money already on hand at the beginning of the year (fund balance). A balanced budget can be represented by the following equation:

Expenditures = Revenues + Withdrawals from Fund Balance

Thus, if a local government plans to spend $1 million, it must have a total of $1 million in revenues and fund balance withdrawals. If it plans to raise only $900,000 in revenue, it needs to be able to withdraw $100,000 from the fund balance. If it plans to raise $950,000, it will need to draw only $50,000 from the fund balance. If it plans to raise $1,050,000 and plans to spend $1,000,000, it will be able to add $50,000 to its fund balance.

The City of Concord, N.C. regularly wins awards for its annual budget presentation. Explore their budget plan online

Local government revenues come from property taxes, sales and other local taxes, and user fees and other sources. A budget is based on revenue estimates—educated forecasts about how much money the city or county will receive during the coming year. To be safe, local officials often plan to spend nothing from the fund balance. That is, they budget expenditures equal to or slightly less than estimated revenues.

The fund balance is like the local government’s savings account and helps the government deal with unexpected situations. If actual revenues are less than expected, the government can withdraw from the fund balance to make up the difference. If revenues exceed actual expenditures, the money is added to the fund balance. If a government regularly withdraws from its fund balance, it will eventually use its entire savings and have no “rainy day” money left.

In North Carolina, annual budgets run from July 1 of one calendar year to June 30 of the following calendar year. This period is called the government’s fiscal year because it is the year used in accounting for money. “Fiscal year” is often abbreviated “FY.” FY 2020, for example, means the fiscal year from July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020. Each year the local governing board must adopt the next annual budget before the new fiscal year begins on July 1.

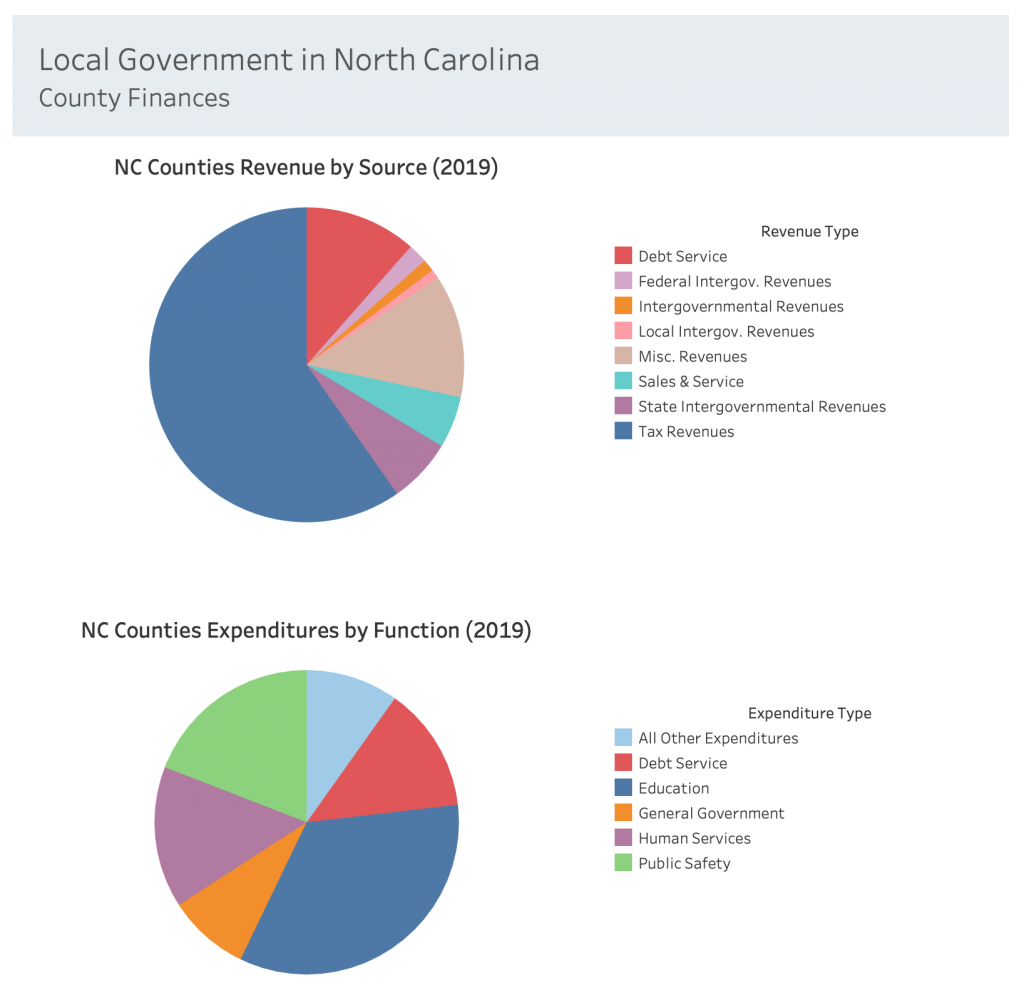

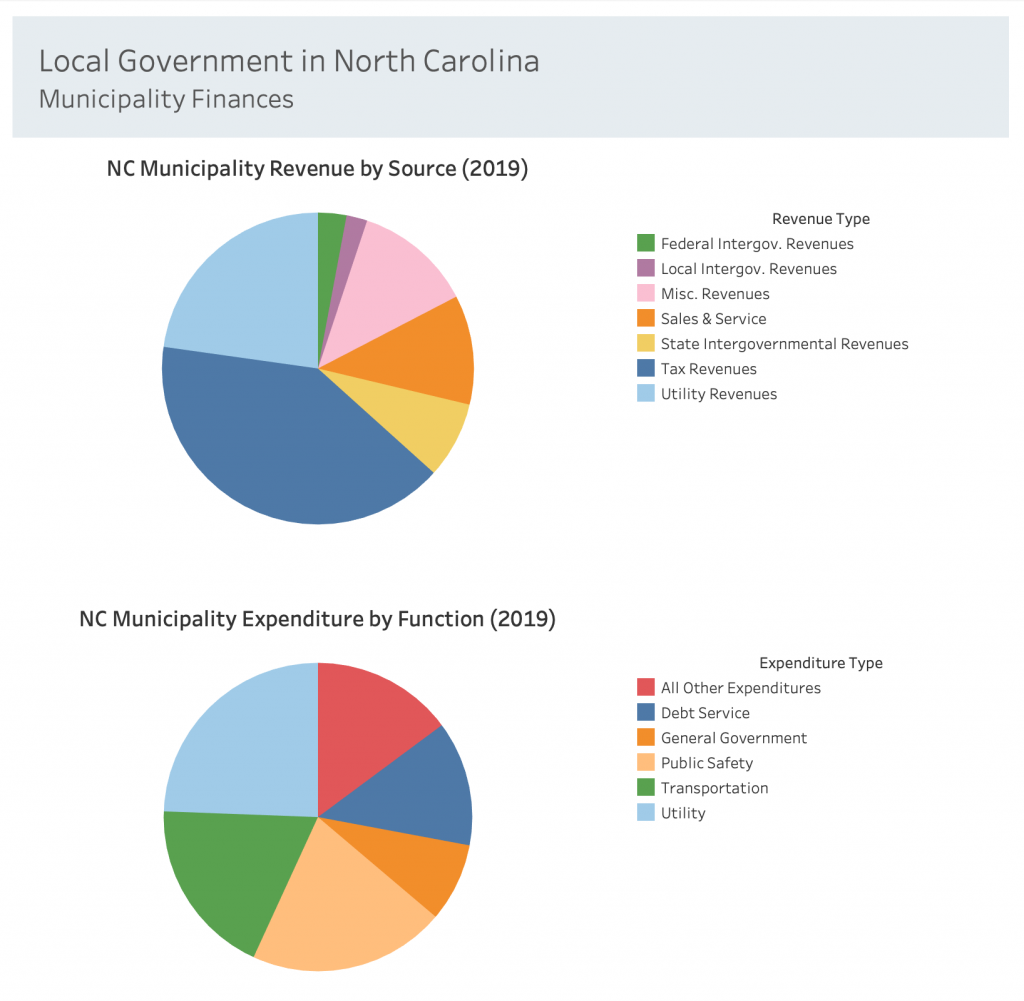

Each local government’s budget reflects the priorities chosen by the local governing board. Local government budgets also reflect the way the General Assembly has allocated service responsibilities. In North Carolina, municipalities spend much of their money on utilities, public safety, and transportation, including streets. Counties spend most on education, public safety, and human services.

Deciding What to Fund

Several months before a new fiscal year begins in July, local government departments estimate how much more or less their services will cost in the coming year. For example, if a solid waste collection department is going to continue collecting the same amount of trash from the same number of places at the same frequency, its costs will be about the same. Fuel for the trucks may cost a little more, but if services do not change, next year’s expenditures would be similar to this year’s expenditures. If, however, the city council decides to reduce the number of trash collections from twice a week to once a week, the department can reduce the number of employees and the number of miles driven by the trucks. The department will pay less for salaries and fuel bills. Perhaps the city will not have to buy new trucks as often, too. The change in services will therefore reduce estimated expenditures for the department.

On the other hand, if in the coming year there will be many new households due to new construction, or the city decides to increase how often it collects garbage, the department may need to add trucks and crews to collect trash. These new expenses for additional service will add to estimated expenditures for the department.

After department heads determine how much money they think they will need for the next fiscal year, they discuss these estimates with the manager. The manager also looks at expected changes in the other expenditures. For example, employee salaries may have to be increased for the local government to stay competitive with private employers. Salary increases and other government-wide expenditure changes are usually not included in departmental budget estimates. In addition to the department requests, the manager must add these increases to the projected expenditures.

At the same time, the manager also prepares revenue estimates for the coming year. After all the estimates for both expenditures and revenues are complete, the manager compares the totals. If estimated revenues exceed estimated expenditures, the manager may recommend lowering local tax rates, adding to the fund balance, or expanding programs and services. If estimated expenditures exceed revenues, the manager may recommend cutting expenditures, raising taxes or fees, or making withdrawals from the fund balance. It is the manager’s responsibility to propose a balanced budget to the governing board.

The governing board reviews the manager’s proposed budget. The manager also provides the board information about the current year’s expenditures and revenues compared to the budget for that year. Board members usually pay particularly close attention to proposed changes in spending to decide whether the services their government provides are the best use of public funds. They also pay careful attention to proposals to raise tax rates or the fees people pay for services. The budget they adopt must be balanced, too.

Before the governing board adopts the budget, it must hold a public hearing. This provides people in the community an opportunity to express their views about the proposed budget. At any point in its review, the board can change the proposed budget. The annual budget must be adopted by a majority of the board. The coming fiscal year’s annual budget must be adopted before the end of the current fiscal year on June 30.

In adopting the budget, the governing board appropriates (authorizes) the expenditures for each department for the coming the coming fiscal year. The finance officer keeps records of all expenditures. Before each bill is paid during the year, the finance officer checks to see that there is enough money left in the department’s budget appropriation to pay that bill. Expenditure records also help the manager coordinate government operations and plan the next year’s budget. If the government needs to spend more than the amount listed in the budget for a particular purpose, the governing board must pass a budget amendment.

When it adopts the budget, the governing board also sets the property tax rate and adjusts user fees to provide sufficient revenue to balance the budget.

Capital Projects

When a city buys land for a new park or a county builds a new jail or landfill, the project usually costs too much to be paid for from current revenues or from the fund balance. Major purchases like land, buildings, or very expensive equipment are called capital improvements. Local governments usually borrow money to finance these projects, although annual revenues or the fund balance may provide enough for smaller projects.

Local governments that borrow money must repay what they have borrowed—the principal—plus interest. Typically, these payments are spread over several years and are called debt service payments.

Borrowing money has several disadvantages. First, it is expensive. The borrower (in this case, the city or county) must pay interest to the lender. Borrowing also commits the government to payments on the debt for a period of years, often 20 or more. Debt service payments will need to be included as expenses in each annual budget until the debt is paid off. For these reasons, North Carolina state law prohibits borrowing money to pay for local government operating expenses.

However, borrowing for capital projects also has advantages. One advantage is that by borrowing, the government can do the project right away. A new landfill or jail may be needed very soon—much sooner than the government would be able to save enough to pay for the project. Another advantage to starting the project right away and borrowing money to pay for it is that the costs of land and construction may go up while the government waits for funds to become available. So while there is a cost in terms of interest to borrowing, there can also be savings due to avoiding inflation, meaning higher costs in the future. Debt-financing capital projects also means the residents who benefit from the capital investment pay for it while it is being used. If a local government saves for many years to fund a future capital project, that means current residents are paying for a benefit for future residents. For these reasons it is quite common for local governments to borrow funds to debt-finance capital improvements for their communities.

Governments borrow money by issuing bonds. Two kinds of bonds are used by North Carolina cities and counties. General obligation (G.O.) bonds pledge the “faith and credit” of the government. That is, the local government agrees to use tax money if necessary to repay the debt. Bondholders can even require local governments to raise taxes if necessary to pay the debt. Revenue bonds are repaid from revenues the funded capital project itself generates. For example, revenue bonds could be used to pay for a new parking deck, with the debt service being paid with fees charged to those who park there.

Under the North Carolina constitution, G.O. bonds cannot be issued unless a majority of the voters approve them by referendum. G.O. bonds are typically used for nonrevenue producing projects like schools, courthouses, parks, or jails. Sometimes government officials also prefer to use G.O. bonds for revenue-producing projects like sewer plants, parking decks, or convention centers. This is because G.O. bonds usually have a lower interest rate than revenue bonds. Investors feel more secure about the repayment of their money when a bond is backed by local government’s power to tax.

The County and Municipal Fiscal Analysis Tool, developed by the N.C. Local Government Commission, allows local governments to create fiscal reports for the county or municipality and compare fiscal benchmarks for different units of government.

Property Taxes

Property taxes are usually the largest single source of revenue for a local government, sometimes providing more than half of all revenues. Additional sources of local government revenue include other local taxes, user fees, and funding from other sources, including state and federal governments. The pie charts above show the overall breakdown of revenue sources for municipalities and counties in North Carolina.

Both city and county governments levy property taxes based on the assessed value of property. County government is responsible for assessing property. Real property must be reassessed every eight years, although some counties reassess more often. Personal property (cars, trucks, business equipment) is reassessed each year. According to North Carolina law, tax assessments should be at the fair market value of the property. That is, the assessed value should equal the likely sale price of the property. If a property owner thinks an assessed value is too high, he or she may appeal it to the county commissioners when they meet as the board of equalization and review.

Economic development increases the value of property in a city or county, thereby increasing its property tax base. New real estate developments are assessed as they are completed, so they immediately add to a jurisdiction’s total assessed value. Unless there is new construction, however, real property is reassessed only every eight years in most counties. The market value of property may change a great deal during the eight years between reassessments. When real estate prices are rising, reassessment results in a larger property tax base. When real estate prices fall, as happened after the great recession of 2008, reassessment decreases the property tax base.

The property tax rate is the amount of tax due for each $100 of assessed value. If a house and lot are valued at $100,000 and the rate is $.50 per $100, the tax due on the property will be $500.

The property tax is one of the few sources of revenue that the local governing board can influence directly. For this reason, setting the property tax rate is often the last part of budget review and approval. To set the rate, local officials must first determine how much the city or county needs to raise in property taxes to balance the budget. All other estimated revenues are added together. Then the desired change in fund balance is added (or subtracted) from those revenue estimates. The resulting figure is subtracted from the total expenses the local government plans to have. The remainder is the amount that must be raised through property taxes.

To set the property tax rate, the amount that the government must raise through property taxes is divided by the total assessed value of property in the jurisdiction. The result is the amount of tax that needs to be raised for each dollar of assessed value. For example, if a city has a total assessed value of $500 million and needs to raise $3 million from property taxes, its property tax rate would be $.60 per $100 of assessed valuation.

$3,000,000/$500,000,000 = .006 .006 x $100 = $.60

The higher the assessed value of taxable property, the lower the tax rate needed to produce a given amount of revenue. If the assessed value of property in our last example were $600 million, the city could raise $3 million from property taxes with a property tax rate of only $.50 per $100 of assessed value.

The property tax rate for the next fiscal year is set by the local governing board when it adopts the annual budget. Sometimes there is considerable controversy over raising the property tax rate, as homeowners are naturally well aware of their property tax bill. Property owners get a bill from the local tax collector for the entire amount each year. Thus, people know exactly how much they pay in local property tax. In contrast, the sales tax is collected a few pennies or a few dollars at a time. Few people have any idea how much they pay in sales tax over the course of a year.

Most property owners pay their taxes. In North Carolina, more than 97 percent of all property taxes are paid each year. When taxes on property are not paid, the government can go to court to take the property and have it sold to pay the tax bill.

Raising Property Taxes 10 Percent in Wake County

No one likes raising taxes, and across North Carolina, raising the local property tax is a very politically unpopular decision. Yet when newly hired Wake County Manager David Ellis closely analyzed the demand for critical public services and the revenue needed to meet that demand, he and his staff concluded that a 10 percent property tax increase was needed. Despite the unpopularity of raising taxes, especially of such a large increase, Mr. Ellis recommended the 10 percent tax increase for the FY 2020 Wake County budget. “My budget recommendation reflects the priority needs we must address to deliver those services at the level our growing population expects and as state regulations require,” he said in a news release accompanying the recommendation.

After much public input and deliberation, the Wake County Board of Commissioners voted 6-1 to adopt Mr. Ellis’ proposed budget, including the 10 percent increase in the property tax rate (from 65.44 cents per $100 valuation to 72.07 cents). The tax increase means an extra $66.30 for every $100,000 of assessed value. So someone owning a $300,000 home would expect to pay about $200 more per year in property taxes.

While most of the additional revenue would go to $45 million in increased appropriations to Wake County Public Schools, it also provides for 14 new positions in the Child Welfare Division, more funding for the board of elections, technology upgrades and security improvements, and expansion of library services. Budget decisions ultimately reflect the values of a community, and for rapidly growing Wake County, raising the property tax to improve and expand services was seen by many (including a 6-1 majority of the board) as part of the county’s growth and progress.

Property tax bills are sent out in August, early in the new fiscal year, yet no penalties for late payment are imposed until January. Therefore, most people wait until December to pay their property taxes. Local governments must pay their bills each month. They cannot wait until they have received property tax payments to pay their employees and suppliers. This is another reason the fund balance is important. Local governments need to have money on hand to pay their bills while they wait for property taxes to be paid.

Sales and Other Local Taxes

Sales taxes provide a substantial part of most local governments’ revenues. The General Assembly limits local government sales tax rates. Many counties have already reached those limits, so local officials have little control over how much money the sales tax produces for local government. The amount of revenue from this source in any year depends on economic conditions. The more people spend on purchases, the more local government will receive from sales taxes. When the economy slows down and people buy less, sales tax revenues go down as well.

State law permits each county to levy a tax of $.02 on each dollar of sales in the county, and all the counties do so. If voters approve by referendum, counties may add an additional $.0025 for a total of $.0225. The state levies an additional $.0475 on all sales except food. The county tax is applied to food, as well as other purchases. Some counties have special authority to levy an additional half-cent tax on sales to fund mass transit.

Businesses collect the state and county taxes from their customers at the time of sale. The state then collects these tax receipts from businesses throughout North Carolina and returns the local portion to local governments in the county where the sales were made.

Sales tax revenues are divided between county and municipal governments according to formulas established by the General Assembly. Each board of county commissioners decides whether sales tax revenues will be divided with that county’s municipalities based on a population formula or by the amount of property taxes collected in each jurisdiction. Municipal boards have no control over how much sales tax revenue the municipality receives.

Other Local Taxes

Local governments are authorized to levy taxes within their jurisdictions for the privilege of doing business or for keeping a dog or other pet. Cities can levy a motor vehicle license tax. More than 85 counties and a few cities have authority from the General Assembly to levy occupancy taxes on hotel and motel rooms. A smaller number of local governments have authority to levy a tax on the price of restaurant meals. The General Assembly limits the amount of each of these taxes.

User Fees

Local governments also raise revenue by charging fees for some of the services they provide. Cities and counties with public water supplies and sewer systems charge water and sewer customers based on the amount of water used. Some North Carolina cities also operate electric utilities and charge customers for the electricity they use. Local governments charge a fee to swim at a public pool or play golf at a public course. Cities may charge a fare to ride public transportation. These charges are all based on the cost of providing the service. The people who use these services help to pay for the direct benefits they get from them.

In many cases, users do not pay the entire cost of providing the public service. Governments subsidize some services because the public also benefits from the service. For example, city bus fares are usually heavily subsidized because if people ride buses, fewer cars are on the streets. Bus riders help reduce traffic congestion and parking problems, so people who drive their own cars benefit from city buses, too.

Local governing boards have the authority to set user fees. Next to the property tax, fees are the largest source of local government revenue that local officials can control. As local governments have been asked to do more, officials in many jurisdictions have begun to increase fees to raise needed revenue. Fees for collecting solid waste have been established, for example, and fees for building inspections and other regulations have been increased to cover more of the costs of conducting regulatory activities.

Increased reliance on fees means that more and more of the cost of public service is paid directly by the customer who gets the service. Less is paid as a subsidy from other sources, meaning the cost for each user goes up. When the public has a great interest in seeing that everyone gets the service, regardless of ability to pay, user fees are kept low, and taxpayers subsidize more of the costs of the service. Fees set at the full cost of service may mean that public benefits are lost. For example, if bus riders have to pay the full cost of buying and operating the buses, fares may be so high that most riders choose to have their own cars, adding to traffic congestion and the need for more streets and parking.

Other Local Government Revenues

Motor fuels taxes are key revenues for most municipalities. North Carolina has a separate tax on the sale of gasoline and diesel fuel. A part of this tax is distributed to each municipality in the state. Also called Powell Bill funds, these revenues can be used only for the construction and maintenance of city streets. In FY 2018, more than $147 million in Powell Bill funds were transferred from the state to cities and towns. Counties have no responsibility for building and maintaining roads, so they get no Powell Bill funding.

Because the gasoline tax is a tax on each gallon of gasoline purchased, when gasoline prices go up and people buy less gasoline, Powell Bill funds go down. This leaves cities with less money for streets.

Cities and counties also receive money from the state for taxes on such things as beer and wine sales. The state also pays local governments money to replace some of the revenue lost when the state removes some property from the local tax base. The General Assembly sets these tax rates and determines how the funds will be distributed, meaning local officials have no control over these revenues.

Other Local Revenues

When a city or county extends water and sewer lines to new areas, the owners of the property getting the new lines typically pay the local government a special assessment. This payment helps cover the cost of constructing the new lines. Having public water supplies and sewer service available to the property increases its market value, so the owner is charged for the improvement.

Fees for Expanding Water and Sewer Service

Developing new subdivisions or other urban uses often depends on local governments increasing the capacity of their water and sewer systems. To pay for expanding their utility systems, local governments have charged special assessments or upfront fees to the companies developing the land. Real estate developers have long opposed these impact fees. In 2016 a case between a developer and the Town of Carthage went all the way to the North Carolina Supreme Court. The court invalidated certain types of upfront charges. The court found that local governments did not have the authority from the state legislature to impose these fees.

The next year the North Carolina General Assembly passed a new law called the “Public Water and Sewer System Development Fee Act” that authorized local governments to assess upfront charges, under specific guidelines. That law was further amended in 2018 and local governments updated their fee schedules. They followed very specific steps to adopt new system development fees.

System development fees thus continue to be an important source of revenue local governments utilize for expanding infrastructure. These fees remain unpopular with developers who must pay the fees or pass them on to customers. But they remain popular with local governments as a way to place the cost of expensive capital projects on those that directly benefit from them.

Interest earned on the fund balance can be another important revenue source. Most local governments try to maintain a fund balance equal to 15 to 20 percent of annual expenditures. This provides a ready source of funding for months when tax collections are slow. A sizable fund balance can also help cover an unexpected decrease in revenues. Until the funds are needed, the fund balance is invested, and the interest earned is added to government revenues.

State and Federal Aid

Local governments get some of their revenue from state and federal governments. Grants and other aid programs help local governments meet specific needs. During the 1960s and 1970s, intergovernmental assistance was a major source of local revenue. During the 1980s, many federal grant programs were abolished or greatly reduced and intergovernmental assistance became a much smaller part of local government revenues. Still, several important aid programs remain.

Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) help cities and counties improve housing, public facilities, and economic opportunities in low-income areas. Projects funded under this federal program include installation of water and sewer lines, street paving, housing rehabilitation, and other community improvements.

Many social service benefits, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Medicaid, and Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP, commonly known as food stamps) are paid largely with federal funds. State grants also help to pay for some social service programs, but county departments are the ones who administer them. Counties are responsible for determining who is eligible and seeing that appropriate benefits get to those who qualify.

State and federal funds also help support public and mental health services. A complex set of programs and regulations governs how these funds are used.

Take Action

✔ Find the current budget of the local government(s) where you reside and examine the sources of revenue and major categories of expenditures. To what extent does the budget reflect your sense of your community’s values?

✔ Use the N.C. Local Government Commission’s County and Municipal Fiscal Analysis tool to compare local government expenditures across different jurisdictions (for example, neighboring jurisdictions of similar size). What differences and similarities do you see? What explains differences in revenues and expenditures?

✔ Find out when your local government(s) will be holding budget hearings for the next budget (typically sometime in the late spring) and attend one.

the 12-month period used by the government for record keeping, budgeting, taxing, and other aspects of financial management

money a government has not spent at the end of the fiscal year

the income that a government collects for public use

money spent

estimations of future revenue used for planning and budgeting future expenditures

authorizing expenditure of government funds to a particular purpose or use

a percentage of the assessed value of property that determines how much tax is due for that property

a charge levied to use a public service

acquiring, expanding, or substantively improving major tangible items like land, buildings, or expensive equipment

the amount of money borrowed

a charge for borrowed money that the borrower agrees to pay the lender

payments of principal and interest on a loan

the rate of increase of commonly purchased goods, indicating declining purchasing power of currency over time

a contract to repay borrowed money with interest at a specific time in the future

a loan that a government agrees to repay using tax money, even if the tax rate must be raised

a specific type of government bond where payback of the debt comes from revenues of the project the borrowed money paid for

a way for citizens to vote on state or local government decisions; an election in which citizens vote directly on a public policy question

a percentage of the amount borrowed that the borrower agrees to pay to the lender as a charge for use of the lender’s money

a tax based on a portion of the assessed value of real (buildings and land) or personal (all other tangible) property

the value assigned to property by government to establish its worth for tax purposes

land and buildings, and improvements to either

tangible property that is not part of land our buildings, such as cars, boats, and expensive business equipment

the total assessed value of all taxable property

the sum of the assessed value of all the property a city or county can tax

tax levied on a product at the time of sale

support financially

a payment which reduces the cost to the user

a per gallon tax placed on purchases of gasoline

total amount of assets or income that can be taxed

evaluate, measure, or judge something

money given to local governments by state and federal governments to help meet specific needs