Municipal Governments: Cities, Towns, and Villages

Learning Objectives

- Identify municipal government services and facilities that affect your daily life.

- Understand how the N.C. General Assembly influences what municipalities can and cannot do.

- Understand how municipalities are created through incorporation, and how they may expand through annexation.

People live near one another for many reasons: to conduct business, to live near their workplaces, and to enjoy the company of others. There are many advantages to living near others, but there are also disadvantages—issues that affect the community at large. To help people live close together safely and productively, people create municipalities.

In North Carolina, municipal governments are called cities, towns, or villages. These terms carry no special legal meaning in North Carolina. All three terms refer to a municipality created and authorized by the state to make decisions for a community and to carry out the policies and programs that have been approved. In common usage, “towns” are often thought of as smaller than “cities,” but this is not always true. The Town of Cary, for example, is the seventh largest municipality in North Carolina. It had more than 170,000 residents in 2019. In this resource, we generally refer to all municipalities as “cities.”

Cities must be incorporated by the General Assembly. The General Assembly may require the approval of the voters of the new municipality, but it is not required to do so. An incorporated municipality has jurisdiction within its defined geographic boundaries. The General Assembly also approves a municipality’s charter, the rules under which it conducts its business.

Municipal corporations can own property, enter contracts, and be sued. The owners of a corporation give the responsibility of running the corporation to a board. The board acts on behalf of the owners in deciding what the corporation should do. A municipality’s “owners”—the citizens of the municipality—elect the board, which is responsible for running the municipality.

Municipal corporations differ from private corporations in important ways. For one thing, citizens become the “owners” of a municipal corporation simply by living within the municipality’s jurisdiction. They do not buy the corporation’s stock the way owners of a private, for-profit corporation do.

Municipal corporations also have different powers than private corporations. Private corporations can engage in any legal activity they choose. In North Carolina, municipalities can engage only in those activities for which the General Assembly has given its permission, and the General Assembly may change municipal authority as it wishes. For example, the legislature might remove a city’s authority to license taxis or to operate swimming pools, and that city could then no longer carry out the activity. On the other hand, unlike private corporations, municipal corporations are governments. Therefore, municipal corporations are authorized to make and enforce laws and to levy taxes.

Charlotte Airport Dispute: State vs. Local Control

The 2013-2014 dispute over control of Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT) demonstrates how municipalities are “creatures of the state” as well as how significant conflict between state and local governments can be. In July 2013, members of the majority party in the North Carolina General Assembly passed a bill to create a special commission to govern the airport. Much to the dismay of City of Charlotte’s leadership, the new commission was designed to remove the city’s involvement in how the airport would operate moving forward. Leaders in the General Assembly justified the move by saying they hoped to prevent to protect the airport from meddling by the city. Conversely, city leaders claimed that the move was no more than a power grab by the General Assembly.

The City of Charlotte and the newly created Charlotte Airport Commission went to court to settle which institution would run the airport. After months in court and legal fees exceeding $1 million, the North Carolina Superior Court placed a permanent injunction on the issue, effectively ruling that the City of Charlotte would continue to operate the airport as it has had for decades. The court order further provided that the injunction could only be lifted if the commission was granted operating authority by the Federal Aviation Administration. In the summer of 2016, the FAA ruled out that possibility, putting the final nail into the Charlotte Airport Commission’s hopes of running Charlotte Douglas Airport.

The battle over control of the airport was a clash between local, state, and national governments. North Carolina’s General Assembly can and often does preempt the authority of county and municipal governments it has created to do things such as standardize practices across the state or address policy issues that require statewide coordination. But sometimes the General Assembly simply passes local acts to make a political point and remind local governments that they are so-called “creatures of the state.”

In addition to following its own charter, each North Carolina municipality must also obey federal and state laws and regulations. The General Assembly has passed some laws that apply to all cities, while others only apply to cities of a certain size. These general laws provide most of the authority for North Carolina municipalities. However, sometimes a city wants to do something not authorized by general law or by its charter. Often in such cases the city asks the General Assembly to approve a local act. By custom, the General Assembly approves local acts that are favored by all of the representatives to the General Assembly from the jurisdiction that requests the local act.

A new city is generally incorporated after the development of a settlement in the area. Some cities grew up around county courthouses and were then incorporated. Others, like Ahoskie, Carrboro, and Durham, developed around mills or railway stations. The Town of Princeville was incorporated by the General Assembly in 1885, 20 years after former slaves settled it as a freedmen’s camp called “Freedom Hill” at the end of the Civil War. It is the oldest town incorporated by African Americans in the United States.

People ask for their city to be incorporated because they want to have a local government. They want public services, a means for providing public order and improving the community, and the right to participate in making local decisions.

The extension of municipal boundaries is called annexation. When territory is annexed to a city, that territory comes within the municipality’s jurisdiction and its residents become part of the town’s population. Voters in the annexed territory automatically become eligible to vote in city elections, and the city must provide services to the new residents.

Cities may annex territory through an act of the General Assembly, by petition of the owners of the property to be annexed, or by ordinance. Annexation by ordinance requires the city to provide services to the annexed territory. Following a change in state law in 2012, annexation by ordinance must be approved in a referendum of the voters in the area to be annexed.

Rougemont (Un)Incorporated

Creating a new town is an unpredictable process, and the voters of the Rougemont community learned that when they held a special election to become Durham County’s second incorporated municipality. Rougemont is a rural community located in the northwest corner of the county. It is home to just under 1,000 total residents. Some of them had been petitioning for the opportunity to become a municipality for decades. In 2011 they finally got approval from the General Assembly to vote on incorporation.

Those in favor of becoming a municipality wanted a stronger voice in decision-making for their remote corner of the county. Some argued incorporating would spur economic development within their community. Pro-incorporation residents also cited the need for a public water system. Dozens of private wells were contaminated with benzene, a chemical that causes cancer. Incorporating, supporters said, would make it easier for the community to negotiate water prices with nearby municipalities, such as the Town of Roxboro.

Residents opposed to incorporation raised concerns over paying property taxes to support a municipal government. They said they had no desire for more public services. Some people outside the community had concerns as well. Leaders in the City of Durham had long resisted Rougemont’s incorporation. They worried adding a new town would complicate the long-discussed idea of consolidating Durham city and county governments. In response to their objections the General Assembly had blocked incorporation of Rougemont. However, after a compromise where pro-incorporation residents promised to void incorporation if the city and county governments merged, the state legislature allowed the citizens of Rougemont to finally vote on incorporation in 2011.

Rougemont residents defeated incorporation by a 52% to 48% margin. It was a low turnout election. A margin of only ten votes prevented Rougemont from becoming a municipality.

Governing Municipalities

Each municipality has its own governing board, elected by citizens of that city, town, or village. Like the state legislature, a local governing board represents the people of the jurisdiction and has the authority to act for them. In most North Carolina cities the governing board is called a council, although “board of commissioners” and “board of aldermen” are also names for municipal governing boards.

Regardless of whether they are called council members, commissioners, or aldermen, the members of the governing board make official decisions for the city. The governing board establishes local tax rates and adopts a budget that indicates how the city will spend its money. The governing board sets policies for municipal services, passes ordinances to regulate behavior, and enters into agreements on behalf of the municipality.

The voters also elect a mayor in most North Carolina cities. In a few places, however, the governing board elects the mayor. The mayor presides over the governing board and is typically the chief spokesperson for the municipality. In some other states, the mayor is also the chief administrator for the municipality, but this is not the case in North Carolina.

Except for some of the smallest, most North Carolina municipalities hire a professional manager to serve as chief executive. Under the council-manager plan, the manager is responsible for carrying out the council’s policies and for running city government. A manager must work closely with the council in developing policies for the city and with city employees in seeing that city policies are carried out.

Each municipality also has a clerk. In some cities, the manager appoints the clerk. In others, the council appoints the clerk. Regardless of who makes the appointment, the municipal clerk reports directly to the governing board. The clerk keeps official records of the board’s meetings and decisions. The clerk may also publish notices, keep other municipal records, conduct research for the governing board, and carry out a wide variety of other duties, as assigned by the board. The clerk is usually a key source of information for citizens about their municipal government.

Many small municipalities do not have a manager. Where there is no manager, the governing board is responsible for the administration of the town’s business. The board hires and directs town employees and manages the town’s affairs together, as a committee, or assigns day-to-day oversight responsibilities for different departments to different board members. Instead of a manager, some smaller municipalities hire an administrator who helps the governing board direct town business, but who does not have all the powers of a manager. In towns that have no administrator, the clerk often “wears many hats,” in effect holding several different jobs to carry out town business.

Municipal employees do much of the work of city government. City personnel include police officers, firefighters, water treatment plant operators, recreation supervisors, or others who provide services directly to city residents. Their work is supported by other city personnel: accountants, analysts, engineers, lawyers, secretaries, and a variety of other staff. These personnel provide expert advice, train employees, pay bills, prepare reports, and do the many other things it takes to conduct a city’s business.

City personnel are organized into departments. Each department specializes in a particular service, such as police work, fire protection, water supply, or recreation. Typically, the city manager selects department heads. They work with the city manager in planning and coordinating the activities of employees in their departments. In many cities, the manager relies on department heads and/or a personnel department to recruit applicants for city jobs, screen job candidates, and hire new employees. Department heads organize and supervise the employees in their departments.

The people who live in a city also play an important role in providing municipal services. Volunteers help supervise and staff recreation programs, organize recycling, and even fight fires. Citizen advisory committees, boards, and commissions help city councils and city employees review and plan programs. Individual citizens influence city policies through petitions, public hearings, and conversations with city officials. Residents also help carry out city programs. They sort their trash for recycling. They call police or fire departments to report dangerous situations. Many municipal services cannot be provided effectively without the active cooperation of residents.

Municipal governments help people make their communities better places to live. They provide services to make life safer, healthier, and happier for the people who live there. They offer incentives for improving the community. They make and enforce laws to deal with public problems.

The Development of Municipalities in North Carolina

European settlers established the first municipal governments in North Carolina in the early 1700s. Although they encountered Native American villages and sometimes built their own towns on the same sites, the Europeans created municipal governments based on English models. Each town was an independent municipality authorized under English, and later North Carolina, law.

Early North Carolina towns maintained public wells, established volunteer fire departments, and set up town watches to keep the peace. For example, the commissioners of Newbern (as it was then spelled) detailed the duties of the town watch in 1794 as follows:

By 1800, there were more than a dozen municipalities in North Carolina, but only four—Edenton, Fayetteville, New Bern, and Wilmington—had populations of 1,000 or more. North Carolina was a rural, agricultural state, and few people lived in municipalities. The state remained largely rural throughout the nineteenth century. In 1850, Wilmington, the state’s major port, was the only municipality in the state with more than 5,000 residents. Wilmington’s population reached 10,000 in 1870. By 1880, Asheville, Charlotte, and Raleigh also each had more than 10,000 residents.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the North Carolina General Assembly revised the laws regarding municipalities. Under an act passed in 1855, all municipalities were given the same powers. They could tax real estate, liquor dealers, tickets to shows, dogs, and freely roaming hogs, horses, and cattle. They could appoint a town constable (law enforcement officer), regulate public markets, prevent public nuisances, protect public health, keep streets and bridges in repair, and regulate the quality and weight of loaves of bread baked for sale. As time passed, the General Assembly took away some authority and gave additional authority to individual municipalities and groups of municipalities. As a result, each North Carolina municipality may now have a somewhat different set of powers and responsibilities.

Population growth brought the need for new municipal powers and responsibilities. A larger population created new problems for municipal governments. For example, each family getting its own water from public wells became a problem as cities grew and became more crowded. Some cities like Asheville began to provide safe water to residents in the nineteenth century, but in most municipalities water supply and many other services continued to be privately provided.

During the early years of the twentieth century, North Carolina cities grew rapidly. By 1920, 20 percent of the state’s 2.5 million people lived in municipalities. Cities paved their streets as automobiles became common. They also set up full-time police and fire departments and adopted building codes to regulate construction and reduce hazards to health and safety. Cities bought private water and sewer companies during this period or started their own systems to make these services more widely available to their residents. A number of cities even started their own electric utilities to bring electricity to their communities.

Urban growth continued throughout the twentieth century. Municipal services continued to expand to meet the needs of the state’s growing urban population. By the end of the twentieth century, almost all municipalities had public water and sewer systems, paved streets, and police and fire protection. Most municipalities adopted land use regulations. Other services such as garbage collection, parks, and recreation programs also became common in municipalities throughout the state during the twentieth century.

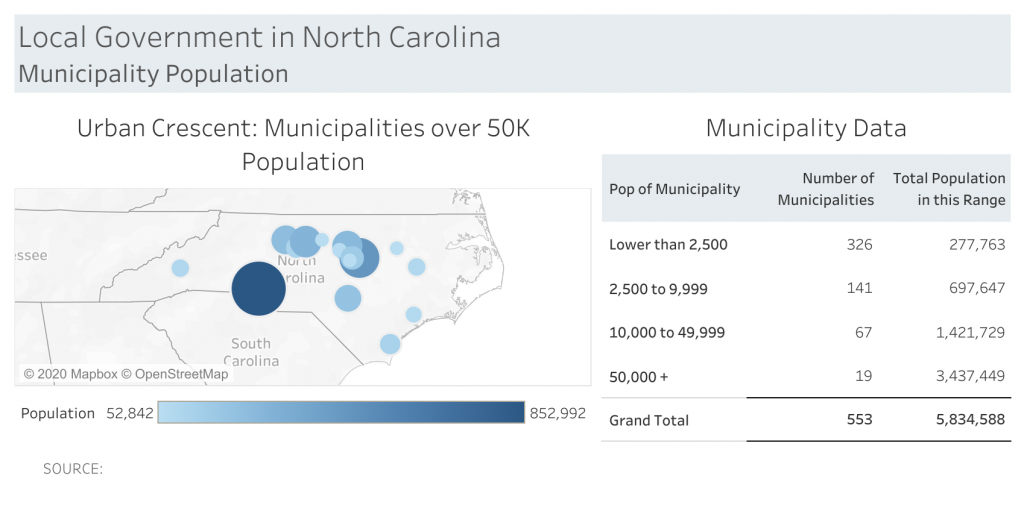

By 2019, Charlotte was estimated at almost 900,000 residents, Raleigh almost 475,000, Greensboro about 270,000, Durham about 275,000, and Winston-Salem nearly 250,000. Most North Carolina municipalities continue to be small places, however. As the table below shows, nearly sixty percent of North Carolina municipalities had fewer than 2,500 residents in 2018.

Take Action

✔ Do you live within a municipality? If so, find out the history of it. When was it incorporated? How has the population changed over time?

✔ Attend a municipal council meeting in your community. Take note of the issues discussed and voted on. Who is in the audience? Did any citizens address the council during the meeting?

✔ See if your local government has a social media page or pages and, if it does, start following it/them.

✔ Does your municipality have a manager? If so, find out about them. What is their background? How long have they been serving as your municipal manager?

✔ Find out about volunteer opportunities in your municipality. Are there citizen advisory committees or boards in your city? If so, find out how one would go about applying to serve on one.

a city, town, or village that has an organized government with authority to make laws, provide services, and collect and spend taxes and other public funds

to receive a state charter, officially recognizing the government of a municipality

North Carolina’s state legislature, which consists of a House of Representatives of 120 members and a Senate of 50 members

the document defining how a city or town is to be governed and giving it legal authority to act as a local government

a group of persons formed by law to act as a single body

to impose a tax by law

to take the place of or take precedence over

a state law that applies to only those local governments specified in the law

the legal process of extending municipal boundaries and adding territory to a city or town

a way for citizens to vote on state or local government decisions; an election in which citizens vote directly on a public policy question

an arrangement in some local governments in which the elected legislature hires a professional executive to direct government activities

the people who work for a government, company, or other organization

a group of residents appointed to provide oversight and advice to a department or to consider a project or issue (also known as an advisory board)