12

Causal Argument

The hiring manager from the evaluation question has hired an ideal employee, but on day two the new worker shows up an hour late. “What happened to you?” asks the boss. “Sorry I was late to work, but we gave my dog a bath last night!”

At this point, will the boss say, “Oh, okay,” or will the boss say “What? So what?” Probably the second one, honestly. What the boss was looking for was an explanation of what caused the employee to be late.

The primary question for causal arguments is “How did we get here?” “Here” is whatever you want it to be, essentially.

- “Why is Tik Tok so popular?”

- “Why is it that breakdancing is an Olympic sport, again?”

- “Why are so many people resistant to raising the minimum wage?”

Questions of “why” or “how” are often answered by causal arguments. During definition we were concerned with what something was; during evaluation we were concerned with how good something was; now we are trying to argue why something is. That new focus means the basic shape of causal arguments will not be criteria-match. Rather, your basic thesis pattern will be “X is caused by Y” or “[claim – phenomenon you are trying to prove] because of [reasons explain why it is so].”

- “Tik Tok has increased in popularity so much because it allows for unfiltered access between creators and consumers of content and because the Chinese government is using mind control waves in the videos,” or

- “Netflix has been spending so much money in recent years on prestige programming because they are confident the critical praise will lead to more subscribers and thus more profits,” or

- “College has gotten more expensive over the last forty years as support from state governments has diminished.”

It must still be an argument, though, so we are not talking about causation in the mechanical or scientific sense; we must have some disagreement about the nature of the process. It is not really an argument to assert that “the decay of yeast creates alcohol,” as that is clear enough; “the explosion which drives the pistons turns the crankshaft and powers the car” is simply a mechanical process – an informational essay, perhaps – and not a causal argument. “HIV causes the body’s immune system to fail, leaving the patient exposed to illness” is likewise well established and not arguable.

You will also want to stay away from settled matters of history, like “The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor led directly to US involvement in World War II,” or “The attempt to cover up the origins of the Watergate Hotel break-in is what sank Nixon’s presidency and caused his resignation.” There is room for innovation here, however, and we will return to these opportunities.

In the absence of criteria-match to create structure for your argument, you are free to use other patterns common in causal arguments. You might, for example, use the “causal chain” to explain how we have moved from A to Z. This pattern is so-called because Event A links directly to Event B, which links directly to Event C, and so on all the way to our terminal event or social phenomenon. When the employee said, “I was late to work because we gave my dog a bath last night” that was skipping from A right over to Z. What the employee should have said was:

“Sorry I was late to work today, boss, but we gave my dog a bath last night, which caused him to thrash around in the tub, which caused water to get all over the floor, which caused my mom to slip and fall, and when she fell she hit her head on the edge of the tub, which caused her to get a head wound, which caused us to go to the ER, which caused us to wait several hours before she was seen, which caused me to be up very late, which caused me to have poor sleep, which caused me to sleep through my alarm, which caused me to wake up late, which caused me to arrive at work late.”

That might have been too much detail, frankly, but at least the boss would be left in no doubt about what happened.

In this scenario, you will argue a progression from one idea to the next, working in a more-or-less straight line until you reach the effect.

The first “Y” or cause in the chain is the “initiating action,” but those are only apparent some of the time. If you can determine with some arguable precision where your series of events begins, you should start there, but most of the time you are just starting in medias res, or “in the middle” – most things that happen are “the middle,” after all. The employee probably gave the dog a bath because the dog was dirty. Maybe the dog was muddy because it had been chasing rabbits across the yard that was wet from the day’s rain. Does that mean your argument starts with the rabbits? The weather? Part of learning to construct solid arguments means recognizing where to begin and end so that your product can be a meaningful part of the process. Thus, you pick a defensible point in the chain – the dog did not have to be bathed – and start there.

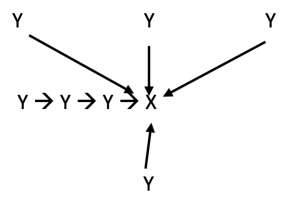

Sometimes this linear argument works quite well, but other times life is more complicated and messier. In that event, you can argue in a “causal web” with multiple series of causes leading to your central phenomenon. Consider the following cascade of circumstances:

Here, for someone to say “four people died because there was a break-in” would not even begin to cover the complexity of the nature of the disaster and would create all kinds of opportunities for counter-argument, as we shall see. Observe that even in this more multi-faceted explanation, there are still several isolated causal chains, like the reasons why the other hired guard did not show up for his shift.

The “chain” and the “web” are not mutually exclusive, then, but are different ways to prioritize the events you need to highlight to make your argument.

Using either the “chain” or the “web,” you could also craft an argument that seeks to predict the future: “The US will go to war with China because of Chinese aggression toward Taiwan,” or “The US and China will put aside their differences over Taiwan and will learn to cooperate in East Asia because it is in the economic interests of both nations.” Just as with any other argument, your thesis must be arguable, so nothing like “The Chicago Cubs and the St. Louis Cardinals will continue their rivalry” or “The population of the US will continue to grow,” or “in the future, there will be more automation.” Predicting the future is very hard – here we are with no flying cars, no Moon colonies, and the hoverboards are a distinct disappointment – but that never stops people from trying. The further out you want to go, the harder it gets because the number of possibilities expands so rapidly. While there is a whole genre of “futurist arguments” about what the distant (generations from now) future will look like, to keep your argument grounded and supportable, you should probably stay in the near term. [1]

Arguments about the future normally rely on a kind of extended analogical reasoning over the top of the causal reasoning – futurists look for patterns in the past and project them into the future, assuming the future will be like the past, but different. Analogies are comparisons between two (or more) things, so using “analogical” reasoning just means to say, “this thing is like that thing.” There are, for example, people who suggest that the US of the early 21st Century looks a lot like the US of the Gilded Age period (c. 1875-1893) in the way that financial and political power is concentrated in the hands of so few, and the wild economic disparity of that period lead to the reforms of the Progressive Age, so the middle of the 2000s might very well see a new era of labor, economic, environmental, and legal reform. More narrowly, there were people who foresaw the collapse of the US housing and mortgage bank bubble in 2008 because they thought the inflated values and the flow of easy money looked a lot like the Internet bubble of the late ‘90s that wiped out many in the first generation of tech “start-ups.”

Strategies for Topics

In terms of thinking about potential topics or effects, one strategy you can adopt is to argue from a surprising cause. This approach allows you to work with more familiar topics, but you are coming at them in a way which asks the reader to consider this new angle. Arguing from a surprising cause does allow you to revisit settled history, for example – which is the opportunity mentioned earlier. It is normally accepted that a complex network of hostile alliances lead to World War I. Serbia was an ally of Russia but hostile to Austria-Hungary. When a Serbian assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia; Russia declared war on the Serbs’ behalf; this action brought Germany in because Germany was pledged to assist Austria-Hungary; this action brought France and Great Britain in because they were pledged to assist Russia; soon millions were dead. Suppose, though, you argued that the geopolitics were just an extended family squabble writ large through nationalism. As you may know, the King of England, George V; the Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II; and the Kaiser of Germany, Wilhelm II; were all cousins, grandchildren of Queen Victoria. It was really their extended “sibling” rivalry that led to such competition and their attempts to overawe one another; each wanted to be seen as the “head of the family.” Thus, WWI was caused mostly by dysfunctional family dynamics, and only marginally by Balkan separatism.

If we go back to the housing bubble bursting, the usual explanation points to predatory lending and profit taking – and the willingness of all the key parties involved to ignore the underlying instability of giving a person with a limited income a $250,000 mortgage on a $150,000 home. While the party lasted, lots of people, like the banks and the mortgage brokers and realtors, made good money, but when the defaults began, there was no stopping the process, and huge financial players, like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, were crushed and went under. More regulation and oversight were often prescribed as solutions to prevent this sort of thing from happening again. But for those to whom “regulation and oversight” are practically curse words, they found a different cause: too much government intervention. They argued that if the federal government had not encouraged banks to make more loans to historically disadvantaged groups, then so many risky loans would never have been offered, and the collapse could never have come. That explanation looks a lot like victim-blaming, but it is certainly arguing from a surprising cause.

Creating your Thesis

You have settled on a topic and decided (at least in draft form) what some of the major causes will be. How does the Toulmin Schema impact a causal argument?

Your thesis here will be the claim that some event or phenomenon, your X, has occurred, is occurring, or will occur.

Claim: College tuition has increased approximately 260% since 1980.[2]

The other half of the thesis will be the reasons, or the causes, the Y, of your X event. By this point, you need to have decided on an organizational pattern. Are you going to argue in a straight line? In a web? Either way, you do not want a thesis which is too long and unwieldy, as it would be if you reeled off six or a dozen causes in your reasons. Instead, you can break your thesis into a couple of different sentences; you can include only the most significant reasons; or you can skip most of the causes in the middle – in other words, you can adopt the employee’s strategy of saying, “I was late because we gave my dog a bath last night.” Then you will explain that you will be filling in all the missing links in that chain. As usual, the reasons are themselves new specific claims, but remember that is simply how it works.

Reasons: because of declining funding from state governments and the competition between colleges to attract students with ever-more elaborate services, all coupled with the normal operation of inflation.

Creating your thesis also creates your first need for proof because you must demonstrate that your X (college tuition increases) is a real thing that is happening and is not some confection whipped up by fevered or alarmist media. In 2016, many voters perceived that the crime rate was rising, when for most violent crime, it was dropping.[3] The problem was that some prominent cities were experiencing a rise in murders, specifically. This odd circumstance – most violent crime going down, but the most violent (murder) going up – should have been an occasion for careful explanations; instead, many used the uptick in murder rate to cry that the sky was falling, so that millions of people, when asked, said they believed the US was in the middle of a crime epidemic and they did not feel safe. If the 2016 version of you wanted to write a causal argument about the rising violent crime levels in America, the first hurdle would have been tricky because there was no such rise, and a thorough check of the FBI Uniform Crime Report would have forced a change in topic or approach, assuming the 2016 version of you was ethical and intellectually honest, of course. In the meantime, the modern version of you should not really have any trouble proving tuition increases are real, so that barrier is cleared. If an arguer cannot prove the phenomenon is real, then what is the point of the argument? Show it is real in a way that would win over your skeptical audience.

Now you can begin to address the part of the argument which is actively causal. In a causal argument, the causes (the Ys) form the reasons, so the evidence for them is the grounds. Just as you had to prove your phenomenon was real, you must prove each reason is real. After all, if the reasons are not actually occurring either, then you will have a serious problem arguing they could be the cause of anything.

Thesis: College tuition has increased approximately 260% since 1980 because of declining funding from state governments and the competition between colleges to attract students with ever-more elaborate services, all coupled with the normal operation of inflation.

This thesis gives us three reasons to create supporting grounds. First, you need to prove – through testimony, statistics, and examples – that state funding has declined considerably since 1980. Some estimates suggest that average state appropriations have dropped from about 65% of college costs before the tax and budget cuts of the early ‘80s to about 30% in 2012.[4] Closer to home, the President of MACC, Dr. Jeff Lashley, has explained that state aid used to make up around 33% of the college’s budget, while today (2021) it accounts for only 15%. Second, you would need to prove – through testimony, statistics, and examples – that colleges have been increasingly competing with one another by offering perks. The University of Missouri, for example, has a Lazy River at its student rec center. This is hardly an academically necessary expense, but it sure is an impressive thing to show prospective students on a tour. Third, you would need to prove – through testimony, statistics, and examples – that everything has gotten more expensive since 1980. Food costs, for example, are up 160%,[5] and those year-over-year pressures just add more to the spiraling costs.

If we imagine that a causal argument looks sort of like this:

Y –> Y –> Y –> result or effect

then for the grounds you are proving that the Ys are real/really happened.

Once your grounds for the causes are squared away, you will need to address the warrants created in your thesis. In a causal argument, the warrant is the assumption that the causes can, in fact have, lead to the effect. If I say, “Candidate X will win because the economy is doing well,” then my warrant is that the robust economy will influence the election. If my reader is not likely to grant that assumption, I will have more work to do. If I make the claim that “poverty leads to crime” my warrant must be that those things are linked; I need to show that link to my readers, which is what happens in the next step, the backing.

The backing here will be the evidence that one thing causes another. Assume for a moment we know that Y and X are true. We have proven X; we have proven Y. If we use the “poverty leads to crime” example, we would know Person H is poor (a Y) and has committed a crime (the X). If I argue that H’s poverty leads to the criminal act (Y X), then I must prove that “leads to” part – that’s the “”; it is the causality. The backing, then, is the explanation of how the two events are causally connected. It is not enough just to say, “Well A happened, and B happened, so A must have caused B.” In fact, that is the post hoc fallacy. You cannot stop after proving the reality of the steps; you must show how the steps are connected.

Showing Connections

Maybe think of it this way: picture a long wall with a series of three or four windows in it. Through the windows at one end, you see a person pass by. A moment later, that person appears in the next window, then the third, then passes the fourth set and passes out of view. The view through the windows is what you have done in the grounds stage but explaining how the walker got from window one to two, and three, etc., is the backing stage. Maybe it “just makes sense” to you, but that is because you already believe it; the whole point of recognizing your audience is skeptical is reminding you to be able to prove it.

Again, note we are not talking about proof for mechanical kinds of things: if the windows are arranged vertically rather than horizontally and somebody falls past the topmost window, then past window two, and so on, you would not have to exert too much energy explaining how gravity works because your audience may be skeptical, but they are still reasonable. Unfortunately, very few causes can be explained mechanically; if they could, it would not be much of an argument, but it might happen.

If we imagine that a causal argument looks sort of like this:

Y –> Y –> Y –> result or effect

then for the backing you are proving that the “–>” are true or valid.

Where the steps and links between them are straightforward enough (giving a dog a bath probably does get the bathroom floor wet) the best approach is to explain them directly. Where that option is not available to you (poverty leads to crime is not as cut and dried), you will need to employ other methods of logic to convince your audience. The most useful is likely to be inductive reasoning, which you may remember as the strategy of observing multiple examples and drawing a conclusion from them. If you get violently ill every time you eat at the “Burritos as Big as Your Head!” food truck, you can infer the food caused your intestinal distress, and you should not eat there again. If you observe that every time you meet somebody at the nearest singles’ bar, it ends badly, you can infer you should switch to a different singles’ bar. For causal induction, there are some more specific helpful tactics.

Thinking about Causes

One of the techniques for inductive thinking is to look for what separate phenomena may have in common. If many people with eating disorders have a stressful family background, that may be a cause of eating disorders. If many people who go to college have parents who went to college, then having college-educated parents may be a factor in a person’s decision to attend college. If many people who own dogs report higher levels of satisfaction with life, then it may be that owning a dog is a cause of greater happiness in life.

A second inductive technique is sort of the flipside of the first – instead of looking for what the results have in common, you can look at significant differences. When cancer rates in many parts of the world spiked in late 1986 and 1987, what was different than it had been before? The nuclear accident in Chernobyl, Ukraine, in April 1986, released massive quantities of radiation into the atmosphere, for the prevailing weather patterns to scatter around the globe. In 2018-19, the Golden State Warriors were one of the best teams in the NBA; in 2019-20, they were one of the worst. What was different? Injuries and Kevin Durant, mostly.

The third inductive thinking tactic is to look for correlations between phenomena. A correlation is a statistical measure of the relationship between two things. It is normally scored on a scale running from -1 to 1.

- A -1 means that the phenomena are strongly negatively correlated, meaning they never happen together, or the direction of change is always in opposition (up vs. down). All things being otherwise normal, the hotter it gets, the less likely it is to snow.

- A 1 means that the phenomena are strongly positively correlated, meaning they always happen together, or the direction of change is always in harmony (up & up). If you eat more food, you will get heavier.

- A 0 means that the relationship is a toss-up, and it is impossible to predict any relationship between phenomena. The number of squirrels and the Cowboys’ playoff chances are not connected, for example.

The problem with correlation is that the direction of the relationship (think of the little arrows) is not always clear, and ultimately correlation does not equal causation.[6] To take a classic example, there is a fairly strong positive correlation between children who play violent video games and who exhibit violence themselves.[7] Some people look at that and say “Oh, video games cause violence,” but it could be just as likely that violent kids choose to play violent games. So which comes first? Members of some religious denominations are more likely to be socially conservative (strong positive correlation), but is it because of their church, or did they choose that church because of their conservatism? Dogs may be a source of happiness, but it is also possible that happy people are more likely to get a dog. Correlation by itself is not a strong argument for cause, but it helps when combined with other evidence.

Exercises

For practice: Try to create plausible causal chains for the following scenarios.

- The United States will go to war with Canada

- The United States will ban self-driving cars

- The United States will require all cars to be self-driving

- Vinyl records will replace .mp3 downloads as the most popular music format

It may also be helpful to think of your reasons as being one of several different types. Causes might be labelled as Immediate or Remote – which are factors of time. You may want to think about arranging your essay according to the timeliness of the causes. An Immediate cause is one that occurs very close in time to the event or effect. In the concert example from earlier, an immediate cause of the deaths would be the fire in the trash can. A Remote cause is one that occurs further back in time from the event or effect. In the concert example, the break-in attempt would be a remote cause. It is easier to argue the influence or impact of immediate causes, but it is often necessary to find and articulate events from further back in time. Just remember that the further back an event is, the greater the number of possible permutations of sequencing, so the connections become more tenuous.

Causes could also be Contributing or Precipitating – which are factors of presence or impact. A Contributing cause is one that is happening or occurring in the present, but as a sort of background noise; if I knew you had a heart condition, and I wanted to scare you into a heart attack, the heart condition is a contributing factor. A Precipitating cause is one that comes to the foreground – me jumping out from behind a door and scaring you would be precipitating to your heart attack.

Third, causes might be Necessary or Sufficient – and you may remember those terms as factors of definition. A Necessary cause is one that must be present for the result or phenomenon to occur: a woman must have been taking fertility treatments to give birth to sextuplets. A Sufficient cause is one that guarantees the result or phenomenon occurring by itself; when my son turned sixteen, that was enough to cause our auto insurance to go up. If a person smokes, that is enough to cause the health insurance costs to rise.

You are not obligated to label your causes at all but doing so may very well help you get a handle on how all the pieces fit, and using the labels well will enhance your ethos as an arguer.

It will also help your credibility if you avoid some of the logical fallacies that are more common in causal arguments; if you can point them out in the work of other writers, so much the better. As alluded to earlier, the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy means you have falsely assumed that just because B came after A, A must have caused B. You must prove the causality – again, that is backing work. The hasty generalization is an inductive reasoning fault and means you have jumped to your conclusion based on too few examples (maybe you have given up on your bar after only one or two duds!). The oversimplified cause means you attribute a complex situation to one over-riding cause: “The Great Recession of 2008 was caused by George Bush” is much too simple. (Note that if you do have a sufficient cause, you must still show how and why it is sufficient).

If we want to think about the structure of the whole, here are some general notes on organization. It is important for you to have decided on an organizational scheme from the beginning: Do you want to go from the past into the present? Start with the present and work into the past? If you are using the “causal web” approach, which of the causes will you address first? Order of importance? Try to do it chronologically? If you are going to predict the future, it is probably most secure to start closer to the present, where the “facts” are more easily demonstrated. There is not necessarily a best pattern here, if the pattern you have chosen is coherent, consistent, and clear to the reader (that is what your intro is for, remember).

If we want to look at the overall organization of a causal argument, it might look something like this:

Examples

Introduction

(assuming the classical argument model)

- Exigency/catchy opening – if the topic is the expense of college, as college students, surely you could think of something relevant here?

- Explanation of context – here, it might be a question of why some problem has arisen

- Thesis: College tuition has increased approximately 260 percent since 1980 because of declining funding from state governments and the competition between colleges to attract students with ever-more elaborate services, all coupled with the normal operation of inflation.

- Make transition.

Body

What pattern have you chosen for your reasons? Will you try to arrange things chronologically, in a causal chain or web, or will you go for something more like order of importance? It is best, of course, if your reasons follow the predictive thesis you used in your introduction, so we will use that precedent; for our example, order of importance.

- Prove that your social phenomenon – here college costs rising – is true.

- “State support for higher education has declined.” This assertion is the “Y” in our sequence, and you must prove it is true. You can look at your state – or likely any state, for that matter – or you can look at national data, but they will all tell a similar tale. You can look at gross dollars, remembering to adjust for inflation/change across time; you can look at support as a percentage of operating costs. Just as a point of pre-emptive rebuttal perhaps, note that if school budgets started increasing, then the percentage of state aid – even if the money remained steady – would look like a decline, so you need to be able to show that is not the explanation for what has been happening. Point out, for example, that even if money remained steady, inflationary action inevitably means that money supports less and less. Once you have shown your “Y,” you must then also prove the “–>,” which is the causality itself. Argue that less state funding must be made up, thus the increased tuition costs. Again, some causal connections will require less work because their warrants are more likely to be widely shareable, but you must not merely assume the connections are apparent or clear, and you must directly address the causality to at least make the links explicit.

- “Colleges compete with more expensive amenities.” You must prove this “Y” true, too. Quote college presidents talking about the pressures to recruit and retain students in a highly competitive world; explain the logic that a place where a lot of students go to school is probably a place where a lot of students would like to go to school – because nothing draws a crowd like a crowd, so the colleges have to be willing to draw a crowd; demonstrate the modern rise of swanky dorms, student rec centers, highly visible sports programs, etc., all designed to capture the student imagination; at the same time, you show that these programs’ costs are borne by the students in the form of tuition or fees. Just as with any other reason, having proved the “Y,” now address the “–>” and show how increased publicity and advertising budgets, sixteen racquetball courts, climbing walls, or multiple dining halls directly add to a student’s cost.

- “Inflation continues to operate.” The simple fact of the matter is that very few things in a modern economy ever get cheaper. Technology (like personal computers) often does after the first few generations, but then it levels off and even at the “cheap” price, will still get more expensive as time goes by. The nature of capitalism is the appreciation of goods and services, and colleges are not immune from these forces. Just because a history professor, for example, is still teaching the same history of Tudor England does not mean the cost of employing that person remains the same: health insurance, competitive salary, and on and on. And that does not even begin to cover the costs of operating the physical plant of the college itself: the heat, the AC, the tar for sealing the parking lots, the increasing complexity of the Wi-Fi network or electron microscopes, and on and on. Everything gets a little more expensive every year, and when there is less money, that gap compounds, and the students get squeezed.

Be sure to prove the “Y” and the “–>” for all the reasons in your chain/web.

- If you have not already done so along the way, now is the time to address rebuttal. The Rebuttal might take at least three forms beyond summarizing the opposition arguments and whatever concessions to opposing strengths you need to grant. First, it is possible someone will argue your phenomenon (X) is not real or really happening; you would have pre-empted this already if you were thorough in point #1, above. Second, a critic might argue that your causes (the Ys) are not real – they did not really happen, etc. You would have addressed this with strong grounds. Third, a critic might argue that your connections (the –>s) are not real – thing X does not lead to the next thing. This would be the position of someone who might agree that Person H is poor and did commit a crime but would point out that most poor people do not commit crimes, so the causality is broken. You would have addressed that with strong backing.

An opponent may also offer a different set of causes. The writer George Will, for example, argues that college costs have primarily risen to capture the increased money available in federal and state student loans. More loan money –> students can spend more –> colleges will charge more.

You would need to be able to prove that Will has the causality almost exactly backward – the federal and state governments have converted much of their funding into loan programs, but that has resulted in less directly appropriated money (which you have already shown), and that leads to budget shortfalls, and that is where you came in. The amount the federal government has made available in Pell Grants, for instance, has had to increase to keep up with the lack of funding;[8] it is not the case that the increasing federal money is causing the rise; it is a result of the rise. The root cause is not greedy colleges, but parsimonious state legislatures. Just as with any other rebuttal, you must also be able to prove these kinds of claims, too.

Conclusion

- Summarize what the readers have learned from your argument.

- Suggest a next step or connect this causality to a larger issue. Now that the readers have learned this thing, what should they do with the knowledge? Support a realignment of state priorities? Look into alternate funding models for college?

- End in some vivid way designed to stick in the readers’ minds; here some education or school-related reference seems suitable: “The next time you want to vent your frustrations about tuition, don’t blame your professor, but call your state senator, then maybe go for a relaxing swim in the campus’s new Olympic-size pool.”

- Unless your teacher wants you write a futurist argument, of course. ↵

- According to the good people at the US Department of Education, for 2014. ↵

- “Uniform Crime Report,” Federal Bureau of Investigation. ↵

- John Quinterno, “The Great Cost Shift.” A Demos Report. ↵

- According to the US Department of Agriculture. ↵

- You should very definitely read “Cause and Correlation” by Stephen Jay Gould in his masterwork, The Mismeasure of Man. ↵

- Shao, Rong, and Yunqiang Wang. “The Relation of Violent Video Games to Adolescent Aggression: An Examination of Moderated Mediation Effect.” 2019. ↵

- “Two Decades of Change in Federal and State Higher Education Funding” – The Pew Charitable Trusts. ↵