9

Research Approaches

Once your thesis is in place and your organizational strategy has been determined – at least provisionally – you are prepared to do the research necessary to fill out your argument. Remember that you need research, in the form of testimony from experts, examples, specifics, details, etc., for both your own support and to diminish the opposition.

While there are many ways to approach research, some tactics are going to be more effective than others. Sometimes students use research as a means to come up with a topic or a thesis. Increasingly, of course, “research” here means the internet. The trouble with going to your favorite search engine and looking for ideas is that it is rather akin to drinking from a fire hose. There is just so much water, coming so fast, you are likely to get very wet and make a mess, but not very likely to have your thirst quenched.

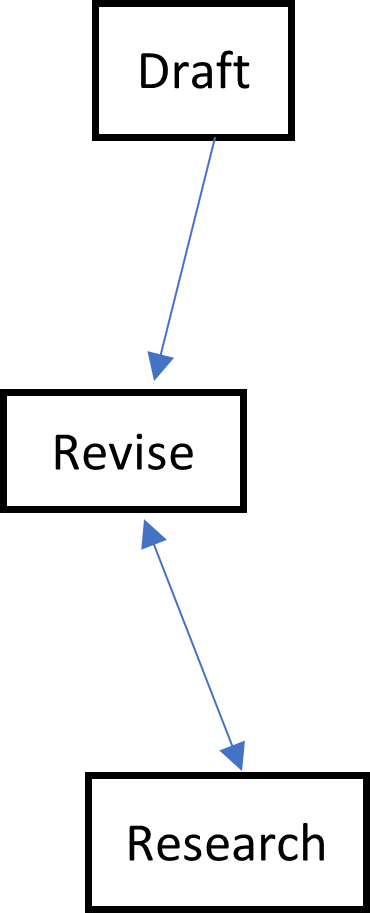

For these reasons, it will be better for you to have come up the preliminary sense of the Toulmin schema on your own: know what you want your thesis to be, recognize what your warrants must be, have some sense of the likely counter-argument. Early in the process, imagine that you do not need research and just write the thing. Then, in the drafting phase of the writing process, put all the pieces in the order that will work best for your rhetorical goals. In this way, you can construct a sort of outline, or frame, for your argument. Doing so will help ensure that your argument means something to you, that you understand the contours of it, and that you have all of it. You review your work, look at all the places you made claims (“Is that really true?” a skeptical audience will ask), and then support those claims.

The chief advantage of this system is that if you know you need to prove, for instance, how many Americans have dogs (to return to our previous example), now you can look that up easily, rather than blindly casting around the subject of “Dogs.” Students often make the mistake of finding some interesting fact but have no idea of its significance or how to employ it, and they wind up just sort of dropping it in somewhere. It is difficult to build a solid argument if you do it haphazardly. If you need to know – because you have referenced it – that most Americans do not really know how much exercise different dog breeds need, now you can look that up in a more targeted way. In other words, make the claims first, then critically search for the evidence you need to support/prove/defend those claims.

Please note this does not mean you are cherry picking or ignoring information to construct the support for a groundless claim. You must be flexible, and if you discover during your specific research that there really is no evidence for a particular claim, or that the evidence points the other way, you must amend your argument or pick something new. For example – to move away from dogs for a moment – suppose you are arguing for prison sentencing reform, and in your draft you make the unsupported claim that most people in prison are there for petty drug offenses. As you are revising, you recognize you need to support that claim, so you look it up and discover that fifteen percent of people in state prisons are there for drug offenses, while fifty-three percent of convictions are for violent offenses.[1] Clearly, you must revise your initial claim; maybe you qualify it in some way; maybe you adjust in a more wholesale fashion. Maybe you point out that even if we released all the drug offenders, the United States would still have the highest incarceration rate in the world,[2] so some reforms are still clearly urgent. At this point you are letting the relevant evidence help direct the argument, not forcing the facts to fit a preconception.

In this way, looking for support while being open to where the research takes you, you will find material you can use for your grounds, your backing, and your rebuttal. The whole point of research is to demonstrate that your argument is substantial and that you understand the context. Good support makes your argument whole and strong, improving your ethos.

Generally, what should you look for in sound evidence, whether on-line or in print? As with many things, experience will be a great teacher, so one of your responsibilities is to become familiar with the kinds of sources likely to be useful to your college-level research. When you have more practice and feedback, your critical discernment will improve, and you have a virtuous feedback loop. That will necessarily take some effort and time, so please ask your teacher many questions about source suitability and use, and always remember to be skeptical about the sources you have found.

Remember that not all material is created equal, so having standards about how to distinguish the good from the meh (and the outright bad) will be enormously useful to you. To help develop a sense of some important criteria, here is a list of several elements you should know and consider as you prepare your draft and reshape your argument.

Who Wrote It?

Find out who wrote the source you want to use. If possible, maybe look at some other work this person has produced – is this person a staff writer for a particular magazine, journal, website? If so, what impact might that have the writing? Is this person a freelance writer? Does this person seem to have a subject focus, like the environment or Chinese politics, or is this writer a generalist? How long does this person seem to have been an active writer? Longevity might not be proof of anything, but if a writer is an absolute hack whose work is unreliable, that is more likely to lead to a shorter career (or possibly a career narrowly recycling the same ideas for the same people).

Who Paid for It?

In the event the work you want to use is anonymous or written corporately (that is, the author is listed as “The Centers for Disease Control” or “The Board of the Harvard University Endowment”), then you want to pay attention to who is paying the bills. Check that — you want to pay attention to who is paying the bills no matter what. Many sponsoring organizations bring no pressure on authors whose work they subsidize, but many very well might, and you want to be alive to the possibility that the makers of Drug X are only going to publish positive reviews or studies on their company website. The Roman rhetorician Cicero once asked the question “Qui bono?” (“Who benefits?”) as a test of the partiality of an argument.

Who Reviewed It?

How many pairs of eyes will read this work before it is made available to readers like you? If the author essentially writes it and then posts it, as with most blogs or something self-published, then it is more likely the work may contain mistakes, solecisms, fallacies, etc. If it is reviewed, though, many of those errors are likely to be caught and fixed. This is especially so if it would cost the organization money or embarrassment to address them later. Good editorial review will also be more likely to produce writing that is easier to understand and is well-supported. Again, this does not mean you cannot use materials with little review; you simply must be aware the source is more open to rebuttal.

Keep in mind, too, that the “news department” of a major newspaper or magazine may maintain one kind of editorial review, while the “opinion [Op-Ed]” pages of the same source may allow a much different editorial tone. As you gain experience, you will eventually learn the tendencies and preferences of various publishers. As an example, there is a great deal of difference between the Washington Post, which is a journalistic newspaper that broke the story of the Pentagon Papers,[3] and the Washington Times, which is a partisan tabloid owned by the Unification Church (the “Moonies” cult).

What Type of Thing is It?

For internet sources, you should also pay attention to what kind of thing it is. While “dot com” is still a kind of catch-all category, the .org, .edu, .gov, or .net might be important information about what we might call the “bias” of the source. A .org, for example, nearly always has some agenda to push – which is not always a problem meaning the material is wrong or twisted, but then again, it might be subtly so. Be skeptical, but not cynical. Typically, a .gov site will have lots of information but very little analysis of that data; the interpretation is your responsibility. Some writers or sponsors or editors might interpret data in ways favorable to their cause; this is natural and if done honestly is simply part of the process. Your part, then, is to be mindful of the range of possibilities.

Is It Enough?

As alluded to in the discussion of the Hasty Generalization, you always want to ensure you have enough evidence to be able to make your case. How much is enough? That is hard to say, and it will change from claim to claim. Your careful consideration of sufficiency is a matter of recognizing that “one and done” is probably not going to do the job. Report from multiple sources, perhaps. Provide a series of brief examples rather than one, etc.

Is It Typical?

Closely related to the idea of sufficiency is that your evidence should be like most of the evidence for a given phenomenon. This idea is sometimes also called “representative.” Do not pick the outlier in a set of data to offer as evidence. A writer who opposed legalizing marijuana because of the case of a man in Florida who went on a six-state crime spree after getting high will have a problem with the typicality of that case. Most users of marijuana do not go on crime sprees, clearly. How will you know if your example is, in fact, typical? Well, consistency across examples is crucial, so one case is not enough to get a sense of likely complexity. Do research in depth to assure typicality.

Is It Accurate?

Maybe it should go without saying that your research should be accurate, but we will be thorough. Given that you will be doing research into many topics you may not know a great deal about, how can you judge the accuracy of the data? One way is to make sure your results are typical; if you find something wildly out of character with the other information you have found, maybe you discount that source. Another way is to make sure the material comes from sources that are clear about authorship, sponsorship, research methodology and sources, etc. Rely on the critical selection of source material to do most of the heavy lifting in the accuracy department.

How Current Is It?

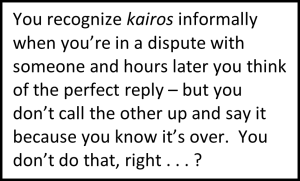

The issue of “kairos” comes from the Greeks, as did logos, ethos, and pathos, and has to do with the “timeliness” or “suitability” of an argument. In its Classical form, kairos is a question of whether the argument is appropriate for the historical moment. If I  wrote an amazing argument about why we should lower the voting age to 18, nobody would publish it because we already did that in 1972. Ditto if I wrote something genuinely compelling about why the United States should not invade Iraq; that question is done and dusted, so the “kairotic” moment has passed. In the context of your research and support, you want to ensure your evidence is of the best moment, that is, that is as recent as possible. “Recent” is a sliding scale, though, because different arguments will create different historical frames. If you are writing an argument about cell phone technology, articles from 2008 are likely too old and out-of-date considering how much the phone has changed since the advent of the first smart phones. At the same time, if you are writing an argument rebutting the nonsense notion that Christopher Marlowe wrote Shakespeare’s plays, that article from 2008 is probably quite timely and still relevant. You will find that some academic disciplines (literature among them) move at a very different pace than others (like technology).

wrote an amazing argument about why we should lower the voting age to 18, nobody would publish it because we already did that in 1972. Ditto if I wrote something genuinely compelling about why the United States should not invade Iraq; that question is done and dusted, so the “kairotic” moment has passed. In the context of your research and support, you want to ensure your evidence is of the best moment, that is, that is as recent as possible. “Recent” is a sliding scale, though, because different arguments will create different historical frames. If you are writing an argument about cell phone technology, articles from 2008 are likely too old and out-of-date considering how much the phone has changed since the advent of the first smart phones. At the same time, if you are writing an argument rebutting the nonsense notion that Christopher Marlowe wrote Shakespeare’s plays, that article from 2008 is probably quite timely and still relevant. You will find that some academic disciplines (literature among them) move at a very different pace than others (like technology).

It is also true that it may be possible to get sources that are “too” recent – the nature of social media and the internet may mean you can get information as it is happening, but that is often too soon to draw conclusions or make evaluations. Journalism calls itself “the first draft of history,” and you will notice that the nature of a draft is that it is likely to change. What would this mean for you? Again, apply some mental acumen to your sources and ask yourself if they meet the standards they should. If you are clear and above-board about the nature of your sources, your ethos will be enhanced as you explain why you have decided to use this material.

Once you have made a thorough search for the best sources to support specific claims you are making or revising, you must not forget to cite these materials. This Handbook does not intend to recap/summarize the entirety of the MLA process because MACC has already produced the Reading, Thinking, Writing Handbook which provides excellent instruction on how to incorporate sources, how to use attributive tags or parentheticals, when to quote or when to paraphrase, and how to create a Works Cited. Please refer to that document to help you through the very important citation phase. Ask your teachers many questions, too! They will love it.

One more special area of research needs to be noted, too, and that is the use of statistics, numbers, etc. It is time to trot, once again, the famous quote sometimes (mis)attributed to Mark Twain: “There are lies, damned lies, and statistics.” What does that mean? It means that numbers – which seem like they are simple facts and thus immune from “interpretation” – can be made to tell outrageous lies or at least create false impressions. To quote from Homer Simpson, “People can use statistics to prove anything. Forty percent[4] of people know that.” At the same time, in the US, we are a society in love with numbers. We have entire websites[5] devoted to numerical analysis, and major sports have been in the grip of “analytics” for nearly twenty years now. In education, students will learn the expression “If you cannot measure it, it did not happen” as a way of making learning a “science” relying on hard data, and pushing away all those soft ideas like feelings, impressions, senses, or believing. In any event, it is true that a well-chosen stat can feel like a clincher, evidence-wise, so many students (and others, for that matter) want to use them. This tendency may prove to be a problem because not everything is subject to numerical summary; the numbers might have been produced in a sloppy or haphazard fashion, and statistics do not speak for themselves; they must be explained.

For all those materials numbers cannot adequately address, we have expert testimony, hypothetical or real examples, etc. Using those elements in conjunction with stats is always best, as number after number can get numbing after a while. For poor statistical craftsmanship, you have your skeptical approach and reliance on accurate, dependable sources. As for the explanations, that is down to you being thorough.

Let us consider a common number we often hear and think about what it means and how it might be explained. In America, divorce in 2019 is often reported at 40 to 50 percent.[6] That sounds very high. At the same time, the Institute for Family Studies was celebrating because the divorce rate hit a fifty-year low of 14.9 divorces per 1000 marriages that year. The second number does not sound so bad. What gives? Here is where the need for explanation comes in. Calculating something like divorce rate is tricky, and it gets more complex when a researcher realizes that the data – much of which comes from the CDC (remember how government agencies gather data but do not do much in the way of analysis?), and their data only comes from states which report it – is incomplete. In 2019, that data set did not include California, our most populous state, and one with probably a few divorces. We could just qualify our claim by saying something like “In most of the US, the divorce rate is about X,” but we would still need to explain why it is only “most.” But that’s part of the problem, is it not? Depending on who you are counting or leaving out, the numbers may veer wildly.

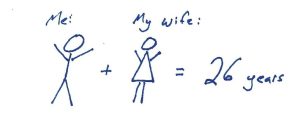

Allow me to offer the example of my own marriage and those of my wife’s aunt.[7] The following is a pictorial representation of my marriage:

See how happy we look? Ahem. Anyway, as of this writing, we have been married for twenty-six years. So far in our data set, no divorces.

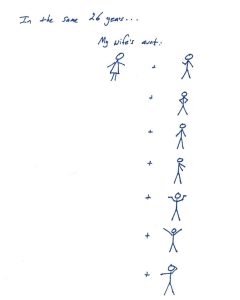

But if we were to expand our inclusive data to add my aunt-in-law, our numbers will change significantly, as this is a pictorial representation of her married life:

Now our data set is eight marriages, with seven divorces.[8] This pool would produce a divorce percentage of something like 87%.

Now our data set is eight marriages, with seven divorces.[8] This pool would produce a divorce percentage of something like 87%.

This example might seem like an arbitrary and silly way to typify the problem, but it does remind us that we always need to explain what is being offered. For instance, are we talking about people getting divorced, or the number of marriages ending in divorce? When you consider that at least five of the men she married were themselves divorced (and three of them multiple times before this marriage), it is possible to make an argument that we have a relatively smaller number of people making up most of the divorces, and as long as you do not marry one of those people, your chance of staying married is higher than one out of two.

Additionally, there is the difference between rate (which uses 1000 as a base) and percentage (which uses 100 as a base) though they are often used together, which also explains the numbers gap and would need to be discussed in an argument. And this analysis does not even begin to cover the complications created by the fact that the number of marriages was also lower in 2019,[9] so there were fewer marriages to dissolve. What would the divorce figure be if comparing year over year? Providing a total or gross number would probably then exaggerate the decline? Sometimes whole/gross numbers can be used to produce one kind of impression: If a writer were trying to argue the centrality of fossil fuel jobs to the economy, that writer might use the total number of related jobs at 9.8 million. Nearly ten million jobs sounds like a lot, yes? But another writer might counter that still makes up fewer than six percent[10] of all US jobs, and that number might not seem quite so irreplaceable. And the complexities of statistics go on and on. In short, a good writer should not simply toss out numbers like they present some finality that cannot be contradicted.

- Kuo, Michelle. “What Replaces Prisons?” The New York Review of Books. 20 Aug. 2020. ↵

- Forman, James, quoted in Kuo. ↵

- Look it up; it’s a fun story – turns out the government was lying about how well Vietnam was going. ↵

- Or “fourteen percent” or “fourthteen percent” or “forthieth percent” depending on how you hear it. ↵

- Like the excellent fivethirtyeight.com, for example. If you want to know what a third baseman’s WAR or VORP is, that site can explain it to you, because I cannot. ↵

- Says the American Psychological Association, for example. ↵

- Who shall remain nameless, to protect the guilty. ↵

- hat’s right, she is divorced from the last guy – so she’s single again . . . ↵

- Again, per the APA and the IFS. ↵

- Department of Labor, Department of Energy, 2019. ↵