10

Definition Argument

If MACC were going to put on a “Talent Show,” what act could you prepare? What would your talent be? Some students could play an instrument, or juggle, or do acrobatics. What about lip-synching along to popular music? Playing air guitar? How about “modern dance” in which there are no moves, just movement? Suppose someone did not really know how to play the piano, but had memorized a sequence of keystrokes that produced a song? Is that a talent? Is she really “playing” the piano at that point? What about speed hot dog eating? And since you brought it up, is a hot dog a sandwich? Is a quesadilla a sandwich?

My son’s chosen mode of athletic performance is cheerleading. He dances, he tumbles, he flips, he picks up other cheerleaders and holds them in the air. He is in shape, but he is sweating, breathing hard, and exerting himself. The state of Missouri says cheerleading is not a sport, though, but an “activity.” Meanwhile, the International Olympic Committee continues to add events like snowboarding, ballroom dance, and breakdancing. So why this and not that?

All these issues are definition issues. That is to say, they ask questions about the nature of a thing: what is it? And therefore, what is it not? While talent or sports may not be earth-shaking questions, questions about constitutes genocide, or treason, or slander may be matters of great urgency, and to address them, we must know how to create a definition that is applicable and defensible. We must argue about it.

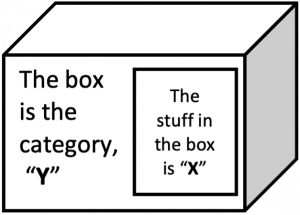

One of the chief reasons to engage in definition arguments is to respond to appeals to what is often called “The Rule of Justice.” This phrase sums up a philosophical precept that all members of a class or category ought to be treated in the same way; that equality is just and therefore moral. You can probably sense this as a basic quality of fairness – although we all know that “fair” is sometimes a loaded word. The French writer Anatole France once pointed out, “the law forbids the rich and the poor from sleeping under bridges,” and no doubt some would say that since laws apply to everyone, that is fair, right? But France was suggesting that “citizen subject to the law” was not the right category, but “rich” or “poor” should be, and a law that looks fair may not be. Nonetheless, if you are a student in Professor M’s Comp II class, you expect to be treated just like your classmates, right? If Student F seems to get away with turning work in late, possibly because he talks St. Louis Blues hockey with Professor M, but when you ask to turn in something late you are told “no,” you are going to feel that is not fair. You believe that if there is a rule about late work, it should apply to all the students in the class. This is the Rule of Justice; your class is your “category” and by virtue of being a member of that category, you have expectations about the application of the policies. If you are enrolled in a course, the categorization is straightforward, but to apply the Rule of Justice in most situations, we need to be able to distinguish between this state and that one. This kind of thinking is called categorical reasoning, and it involves being able to put a little box on the world and creating rules for what belongs in the box, leaving everything else outside the box.

I n the first place, keeping in mind we need disagreement to have an argument, we can quickly deal with what are called simple categorical claims. If we imagine that a Definition Argument requires two terms, let us call those terms X and Y. The X term should be envisioned as a specific, concrete thing, like “cheerleading” while the Y term is the larger, more nebulous category of things, like “sport.” A simple categorical claim exists when all the parties agree on what goes in the box. If someone says, “football is a sport,” that is a simple categorization because no (reasonable) person would disagree. The same would go for non-arguments like “meth is a drug” or “Walt Disney is an infamous person.” Your definition arguments, to go beyond simple claims, must involve X and Y terms that are contested or disputable. Thus, “cheerleading is a sport” requires explanation and is open to rebuttal.

n the first place, keeping in mind we need disagreement to have an argument, we can quickly deal with what are called simple categorical claims. If we imagine that a Definition Argument requires two terms, let us call those terms X and Y. The X term should be envisioned as a specific, concrete thing, like “cheerleading” while the Y term is the larger, more nebulous category of things, like “sport.” A simple categorical claim exists when all the parties agree on what goes in the box. If someone says, “football is a sport,” that is a simple categorization because no (reasonable) person would disagree. The same would go for non-arguments like “meth is a drug” or “Walt Disney is an infamous person.” Your definition arguments, to go beyond simple claims, must involve X and Y terms that are contested or disputable. Thus, “cheerleading is a sport” requires explanation and is open to rebuttal.

What is the best method for creating these boxes on the world? There are multiple approaches, and your teacher may employ any one of them, any combination of them, but there are some more common tactics.

Definitional Approaches

One such method is called an “operational definition.” Essentially, an arguer defines an object by how it is used or operated. I once went into my kitchen to find my wife banging on an apron hook with a coffee mug. When I asked her what she was doing, she explained that she could not find a hammer, so she was using the mug to secure the hook. In that moment, the mug was a being operated as a hammer[1]. In a similar vein, I had a discussion with a class of students about what constituted “breakfast food” – I think we were arguing the wisdom of the breakfast menu at Taco Bell. In any event, we failed to establish any sort of definition other than “breakfast food is whatever you eat first in the day.” Thus, in an operational sense, any food – burritos, tacos, pizza, Cheetos, fully cooked turkey, Little Debbie Oatmeal Crème Pies, etc. — is “breakfast” if it is what you eat first. If I had wanted to qualify the argument, I could have asked my students to define “a traditional breakfast food” but that might not have led to much discussion, as that category of things is less contested (eggs, French toast, sausage, etc.) and therefore more of a simple categorical and less in need of further clarification.

Think for a moment, if it is not too grim, and contemplate the criminal charge of “assault with a deadly weapon.” As it is most commonly understood, “deadly weapon” encompasses a range of things (guns, knives, flame throwers), but that range can be extended to things we do not normally consider weapons. When a white nationalist drives his car into a crowd and his intention is to hurt people, the car becomes a “deadly weapon” by its operation. At the same time, almost anything could be a deadly weapon, could it not? They say John Wick killed three men with a pencil. If a person were sufficiently enraged, a Slinky, or a cell phone, could be used to kill someone. Would that person be charged with “assault with a deadly”? Probably not, because while we may have a categorical sense of “deadly weapon” that is expandable, it is not taffy that can be pulled endlessly in any direction. If anything can be a deadly weapon, then the category loses all meaning and our box on the world falls apart through over-application because now it is essentially coterminous with the world. This elasticity is one of the problems with arguing about operational definitions, as they are so varied and, at some level, impossible to counter. After all, anything can be breakfast.

Second, you might very well rely on a “reported” definition: what relevant authorities have decided defines the concept. The late Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart is remembered for saying he could not define pornography, but he knew it when he saw it. While that is a concept we can probably all apply at some level (“I don’t know how to define heavy metal music, but I know it when I hear it” or “I don’t know how to define comedy, but I know it when I watch it”), it is not very useful way to define things: too subjective. Many courts in our nation’s history, though, have tried to define pornography, or free speech, or privacy, or due process, etc., etc. You might, therefore, refer to legal or other cultural resources and use their definition for your work. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “sport” as: “an activity involving physical exertion and skill in which an individual or a team competes against another or others for entertainment.” That is fine as far as it goes, and it might be a useful place for you to start, but when specifics are applied, it may not be clear enough to base on argument on. How much physical exertion, for example? Is playing a video game (Esports) physical exertion? Reported definitions often cannot cover all the permutations of an argument because they are not, after all, making an argument. The argument must made around them. Please note that if you use another’s definition, beyond the necessary giving of credit, you must still be prepared to defend the logic of the definition with grounds and backing, just as you would with any parameters you created.

A third option brings us to the creation of your own guidelines for defining the box, and to do so, you will likely use a process called “criteria-match.” This method comes (at least partially) from Aristotle and is a “stipulated” definition, meaning you offer your own ideas for what goes in a given box, and defend them according to Toulmin. What you must do now is create your criteria that will define membership in a category. Think of the criteria as the features a Y must have – the traits, the qualities, the features, etc. The enumeration of the criteria creates the “box” and allows arguers to include or exclude specific X terms as needed. Then, when we have constructed a sturdy box, we match an X to the criteria and see which ones do fit and which do not. At the moment, we will just assume that if the majority of the criteria match, we can feel sure of our definition – sure in the sense that we have a viable argument. If we return to the concept of “sport” as our Y term, maybe we want to include a couple of criteria from the OED, so we come up with a draft list:

To be a Sport, Thing X must be/have:

-

- Physical exertion, at times strenuous

- Requires skill

- Individual or team

- Competition

- Entertaining

That might be a fine start, but for a definition to be useful, it must exclude more than it includes. So far, our list means that participating in a baking show is a sport. Or dating, for that matter:

-

- Dating might involve physical exertion, like dancing or throwing axes or . . . rock climbing?

- Dating requires skill, right?

- Dating is individualistic, but there is often a team ethos (“wing man” or “crew”)

- Dating is competitive

- Dating is entertaining in the sense that your friends want to hear how it went

But do we really want to argue that dating is a sport? Probably not, so we need a more well-defined box with tighter guidelines.

To be a Sport, Thing X must be/have:

-

- Physical exertion, at time strenuous

- Requires athletic skill and coordination

- Individual or team-based

- Competition with an agreed-upon and officiated scoring system to determine the winner

- Entertaining for onlookers gathered for that purpose

Our new, more qualified, criteria would eliminate baking shows and dating, since dating does not require “athletic” skill, there is no agreed-upon scoring system with officials, and crowds do not gather to watch people date – unless you count The Bachelor or The Bachelorette, I suppose . . . you can see how involved this could get.

We could try out some more contested borderline cases. How about deer hunting?

-

- Deer hunting does involve some physical exertion, if the hunter drags the deer carcass very far, for example

- Deer hunting requires hand-eye coordination

- Deer hunting could be individual or team-based

- Deer hunting does have an agreed-upon scoring system (Boone & Crockett) and officials (DNR & Conservation)

- Deer hunting does not really gather a crowd, so that one is less of a match

Could we say that deer hunting is a sport? There is an argument to be made.

How about the example brought up at the top of this section, cheerleading?

-

- Cheerleading does involve physical exertion, sometime strenuous

- Cheerleading does require athleticism and coordination

- Cheerleading is team-based

- Cheerleading does have a scoring system, with officials

- Cheerleading does have crowds who assemble to watch

Is Cheerleading a sport, then, despite what MSHSAA says? Again, there is an argument to be made.

Are you starting to see how the process of criteria-match works? If so, you can also see we have the makings of our argumentative thesis: “Cheerleading is a sport [claim] because it involves physical exertion, requires athleticism, is team-based, has a scoring system with officials, and has an audience [reasons].”

Arrangement

There could be many ways to arrange a definition argument, but in one of the most common and useful patterns, the first element we must account for is the warrant of our argument. In a definition argument, the warrant is your list of criteria. Five criteria essentially create five warrants – recall that warrants are plural in complex argument. If Reader A agrees that our five criteria do, in fact, define what a sport is, then that reader accepts the thesis makes sense. If Reader A does not agree, we hope the backing is convincing. In a definition argument, the backing must take the form of explaining why “strenuous physical exertion” is a feature of “sport.” Why is “coordination” an element of sports? Why can sports be individual or team based? Why is “competition” with an “agreed upon scoring system” part of the definition? Why is “entertaining for onlookers” relevant? Answering those questions through testimony, examples, and analogies, etc. is your backing.

Notice that the backing is focused on the category, the Y. Backing will not allude to cheerleading, or deer hunting, etc., but supports the establishing of the category. The grounds are entirely focused on cheerleading, the X. Since the grounds are proof the reasons are true, the grounds in a definition argument would be evidence of the reality of the thesis: You would prove cheerleaders burn so many calories during a two-and-a-half minute routine by citing experts; you would prove the athleticism claim by demonstrating that a person could hardly do six somersaults followed by an aerial or climb to the top of a human pyramid without an advanced sense of coordination; you would prove that most cheer squads number between six and two-dozen people by citing the NCA; you would prove the scoring system by again referencing NCA; and you would prove the crowds claim by demonstrating how many thousands of people show up in Orlando, FL, every year to watch the national finals.

So far so good, yes? We have our category explained with backing, we have our claim, we have our reasons, and we have supported the reasons with grounds.

This division of labor between backing and grounds is important to note because you want to account for all the work a definition needs to have so you are not wasting effort doing the same thing twice. Since the backing for the Y is independent of the X, it is vital that you establish or create your criteria before you apply the X term – if not literally in the essay, then in your drafting process, certainly. If you create a definition of “sport” to fit cheerleading (or whatever), you have retrofitted your definition and thus not developed a useful or applicable box on the world. Ideally, you would develop your criteria for Y and only then think of an X to match, but in the course of brainstorming your argument you will probably come up with a notional thesis first, and that is likely to include the specific term. Of course, there is nothing that says you must come up with the thesis first, and it might do you some good to create categories absent any particular X: What is Art? What is a racist law? What is harassment? What is a song? What is a cult? Having done that, then you can perform the match portion of the program knowing your criteria are legitimate and disinterested.

It is also absolute that you construct criteria for Y which are expressed positively; in other words, “this thing [coordination, for example] is what defines a Y.” You cannot create negative criteria; you cannot define what a sport is not. Now, that might seem a bit confusing since you can claim that “X is not a Y” but that is not the same thing as trying to define a negative. Saying “X is not a Y” just means that X fails to be what a Y is; you cannot define what Y is not. And why not? Because Y is not literally everything in the universe except what defines the box. A sport, after all, might be the above five things, but it is not billions and billions of other things: it is not a flamingo, a river in Montana, the sum of the angles of an icosahedron, a filling meal, a pet, a coat hanger, a comfy chair, a sunny day, an inanimate carbon rod, and on and on and on, ad infinitum. If you started down the path of “a sport is not something you can do sitting still” there is no end to that list of criteria because a sport is not most things in creation. If you think movement (“not sitting still”) is important, then explain it in positive (“is” rather than “is not”) terms: “Sports require movement” could be one of the criteria. Further, in terms of Toulmin and the research you need to be able to do, because you cannot prove a negative, your backing would be complicated and maybe impossible with negative criteria.

I apologize in advance for the digression here, but this is a necessary point to elaborate. If I accused you of being a heroin user, you cannot really prove you are not. You could take a drug test and come back clear, and I could reply by saying it’s simply been long enough for the heroin to pass out of your system. You could argue you have no needle marks or punctures in your skin, and I could reply that you smoke it instead. You could argue there are no people who could come forward who have ever sold you heroin or seen you using it, and I would reply they simply aren’t willing to come forward. At this point, how else could you prove you are not a heroin user? Admittedly, that does not constitute evidence you are a heroin user, but I challenged you to prove you are not, and it is logically very difficult, if not impossible, to prove a negative. So how could we ever argue “X is not a Y”? Your argument in that case must rely upon its specificity and evidence. If I accused you of being a heroin user, that is very general and impossible to argue, but if I said “You used heroin on July 23, 2021,” then you would be in a position to answer because you might very well have witnesses to your behavior on that day: you spent all day in the company of your parents and extended family at the Lake, and they will all swear they never saw you with heroin or acting in any way altered. Thus, vague negative claims cannot exactly be disproven, but you can make rebuttal by pointing out that vagueness, and a more specific claim can be disproven. To be effective in both asserting and negating, be specific – or it may not really be an argument.

Therefore, be deliberate about how you frame your criteria.

Aristotle had some additional refinements for the criteria we might also usefully consider. According to his thinking, criteria could be labelled Accidental, Necessary, or Sufficient. An accidental criterion does not mean the “oops” sense of accident but something more like “incidental,” meaning that criterion might be present, but then again, it might not, and its presence or absence is not wholly crucial to a definition working out. If we look at the five criteria we created for sport, we could treat all five as accidental. Doing so would mean declaring “cheerleading is a sport” would depend on cheerleading meeting a simple majority of the criteria, for instance.

A necessary criterion, though, as the name suggests, must be present for X to be a Y. A “senior citizen” must be over 65; to score a goal in soccer, the whole of the ball must cross the whole of the line; to be a Gemini, one must be born between May 21 and June 21; etc. You are free to argue the necessity of any criterion, recalling that you still must explain why it is necessary – you cannot simply say so and expect your skeptical audience to simply nod and agree. Thus, you could argue that our first criterion above, “physically strenuous” is first because it is necessary; a thing cannot be a sport without being physically strenuous. If you wanted to, you could argue that all five criteria are necessary, but if you do that, then if your X fails to match even one of those necessary criteria, it does not belong in the box. You could have a list of a dozen criteria, with one that is necessary and eleven that are accidental, and if your final match is 11-1, if that one is the necessary thing, it still is not a positive definition.

Exercises

For practice: Try to come up with some necessary criteria for

- A sandwich

- Music

- Sexual harassment

Would any of those concepts have a sufficient criterion? What might an example be?

** Fun fact: The Irish Supreme court ruled in 2020 that Subway bread is more properly cake because of its sugar content.**

The third label, a sufficient criterion, means that by itself the presence, that is, the matching, of the criterion is enough to assure a positive definition. This situation is the sort of reverse of the necessary scenario; here, if the final tally is 1-11, but that one is sufficient, then X is a Y. Are you thinking “What if one of the other 11 was necessary, though?” That seems fairly unlikely, frankly. Anyway, putting your hands on a coworker is sufficient to meet the current federal definition of workplace harassment, for example. Do you also have to have told ugly jokes or made lewd suggestions? No, because any one of those things is enough. As with “necessary,” you are free to argue the sufficiency of any criterion, again recognizing the burden of proof remains with you.

To pause and recap: Most of the confirmatio or positive part of your argument will be your creating of your definitional category with all the backing necessary, and then the grounds proving the matching (or failure to match) of your specific term to those criteria. The backing and grounds – as always – will be the bulk of the actual content of your argument. They are not the entirety of your argument, though, and now you must turn your attention to the rebuttal.

In a definition argument, the likeliest modes of rebuttal will take the form of someone who argues against your criteria for Y or against your match to X, or against your backing and your grounds. As you research, (and remember to read as a believer, as necessary) you will need to see what form the opposition takes. It may be that some other arguer has a completely different set of criteria for what defines a sport. In that case, you must argue that other set is weak or flawed somehow, and that your set is superior in completeness or clarity or whatever. Probably, some of the criteria will be the same, but some important differences may exist, and then you will address those. For instance, you may run across somebody who asserts that “a sport must have an outcome determined by the participants and not subjective judges” – that criterion would not match cheerleading, and if the arguer had insisted it was a necessary element, it would eliminate cheerleading from the sporting family. Of course, it would also eliminate ice skating, gymnastics, and boxing (unless they fought all matches to a knockout), and those are fairly well settled as sports – which is what you would point out in rebutting that criterion’s weakness.

Because no one has really had the chance to reply directly to your argument (you are still writing it, after all), it is unlikely anyone will exactly rebut your matches of X to the criteria, but depending on the criteria you have used, other arguers may have made similar counter-arguments. In other words, a person might agree that “a sport” includes the quality of strenuous physical activity, but that person might deny that cheerleading is strenuous since the performances are so brief. You have probably already shown that cheerleading is, in fact, quite demanding on the body during your grounds when you supported the match, so you might dismiss this counter-claim by referring to your previous work, or you might offer some new data that show basically the same thing in order to rebut the notion that cheerleading would not match.

In the event some opposition arguer makes a good point, you will concede that one to show you are a reasonable person and not some hack incapable of recognizing a valid claim. But you will also go on to explain why that one good point does not overturn your argument. Do not neglect to give yourself the last word, as that is a rhetorically significant position to hold.

When you have acknowledged potential weaknesses in your argument, fairly summarized the opposition, and incorporated and synthesized the relevant ideas by conceding or rebutting them as a skeptic, you have addressed rebuttal and you are ready to wind the argument up.

If we want to look at the overall organization of a definition argument, it might look something like this:

Examples

Introduction

(assuming the classical argument model)

- exigency/catchy opening

- explanation of context – here, it might be an issue of the Rule of Justice, or some question about how to handle a situation depending on what kind of thing it is

- thesis: Your basic pattern will look like “____(Specific X)______ is a ____(Category Y)____ because . . . [reasons]”, so “Cheerleading is a sport because it involves physical exertion, requires athleticism, is team-based, has a scoring system with officials, and has an audience.”

- make transition

Body

At this point, you have a decision to make about the overall organizational strategy. In criteria-match arguments, you have at least two large-scale choices: the Block Method or the Point-by-Point Method. In the block method, you do all your criteria first, then you do all the matching, then you address rebuttal. That is three “blocks” of argument. In the point-by-point method, you explain criterion #1, match X to it, and address any specific rebuttal that may apply. Then you explain criterion #2, match X to it, and address any specific rebuttal that may apply. You repeat this process until you have exhausted your criteria. You may find some rhetorical advantage to choosing one pattern over the other, but it is probably a question of style, so which would you prefer? All things being equal, they both work well, and it is not as though one is typically preferred over the other. The point-by-point requires more transitions, as you toggle back and forth between ideas, but not dramatically so. For purposes of this illustration, we will use the block format.

- Establish the criteria

1.1. The first criterion for a sport is “physically strenuous,” and here is why. Do not neglect the why – it is your backing so must be done well and completely.

1.2. The second criterion for a sport is “requiring athletic skill and coordination,” and here is why.

1.3. The third criterion for a sport is “can be either individual or team-based,” and here is why.

1.4. The fourth criterion for a sport is “Competition with an agreed-upon and officiated scoring system to determine the winner,” and here is why.

1.5. The fifth criterion for a spot is “Entertaining for onlookers gathered for that purpose,” and here is why.

- Match “cheerleading” to the criteria

2.1 Cheerleading is physically strenuous, and here is the proof. Do not neglect the proof – it is your grounds so must be done well and completely.

2.2 Cheerleading requires athletic skill and coordination, and here is the proof.

2.3 Cheerleading is team-based, and here is the proof.

2.4 Cheerleading is a competition with an agreed-upon and officiated scoring system, and here is the proof.

2.5 Cheerleading is entertaining for the crowd, and here is the proof.

- Address Rebuttal

3.1 Acknowledge any potential weaknesses in your backing or grounds. Maybe you used a source with an obvious pro-Cheer bias; admit that but explain why it does not nullify the point or facts the source was used for.

3.2 Fairly summarize any key counter-argument you want to address, and then – now reading as a skeptic – explain why this source is wrong, flawed, or otherwise compromised or inexact.

3.3 Acknowledge any valid points the opposition raises, and then dismiss or neutralize those points.

Conclusion

- Summarize what the readers have learned from your argument. The laziest – and therefore least interesting – way to do this is to repeat your thesis, but you want to be better than that, so put a little thought into it.

- Suggest a next step or connect this definition to a larger issue. Now that the readers have learned this thing, what should they do with the knowledge?

- End in some vivid way designed to stick in the readers’ minds; here some jaunty cheer reference seems tailor-made for the job.

- She has also used a butter knife as a screwdriver more than once . . . ↵