13

Proposal Arguments

You have established that college has gotten a lot more expensive, primarily because state legislatures are failing to support the schools as they once did. Now what? Now you want to suggest a fix, perhaps; you want to make a proposal.

The time has come to embrace the word “should,” as in, “We should do Thing X.” This claim formulation may seem like a natural fit for argument, so it might be surprising it is only making its appearance now, but proposal arguments are surprisingly complex and – when done properly – include many of the elements already discussed, so it is best to have a grip on the others first.[1]

Writing a proposal argument begins with identifying a problem. As you brainstorm this step, you should start with your interests as you survey the world, but remember your audience will have to care, too, so “a problem” cannot be something like “I don’t have enough money,” or “My partner never does the dishes,” or “I can’t stop listening to K-Pop.” Those are all truly troubling, but perhaps not for a general audience, and the likely solutions would not exactly face a lot of rebuttal or opposition. So, the problem you identify must be something your audience can be made to see is serious enough to want to do something about. Once you have thought of an issue, you must be prepared to offer some solution to it. “There is too much bullying in middle schools,” you might say, to which your audience will say, “Yes, but what can we do?” If your response to that is, “Something!” you have failed the crucial test of proposal arguments – having a proposal. Think of having a proposal like a necessary criterion; it is not an argument until you do. It is not called a “notice a problem” argument, after all, so having an answer to that “What do we do?” question is all-important.

Kinds of Proposals

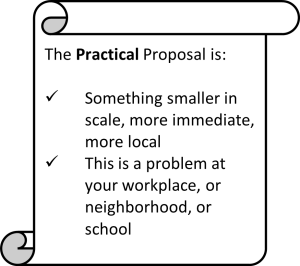

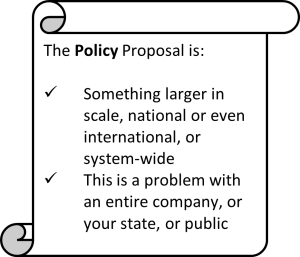

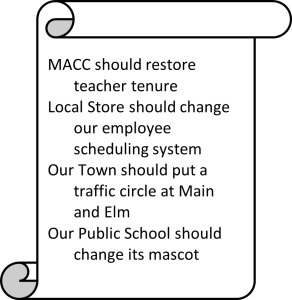

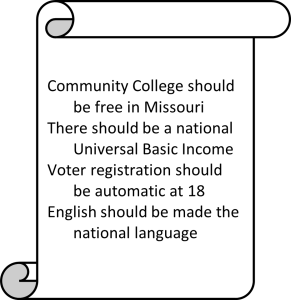

It may help you to come up with problems to recognize there are two basic kinds of proposals. They are not wholly separate, and there is probably some point at which the first thing bleeds into and becomes the second thing, but for our purposes it is hardly worth crafting a heavy bright line; they are different enough to be distinct approaches. The first kind is often called the practical proposal, and the second is the policy proposal. It does not matter which kind you choose to write about, but your choice will affect your audience considerations and your research, so please consider those factors as you contemplate which of the world’s many problems you want to fix.

A potential drawback of the practical proposal is that there is likely to be very little evidence or rebuttal to something hyper-local, so you will have to extrapolate or analogize based on other similar situations about traffic patterns or schools, for example. The flipside is you will know exactly who your audience would be – and you may even know them, literally. These advantages are essentially reversed for the policy proposal because while there is much research on UBI or free tuition, your audience will necessarily be more distant, vague, and harder to appeal to. As with anything, you are free to try several variations as you begin the drafting process to help you decide which approach you want to take. Some combination is possible, but you do not want to be in a situation where you must try to appeal to multiple audiences who may have divergent interests or where you are making the equivalent of two arguments.

Once you have a proposal in mind, you will construct your thesis. For proposal arguments, the claim is your solution to the problem:

Claim: The State of Missouri should expand Medicare to cover all Missourians, effectively creating a single-payer health care coverage for our state.

The reasons you attach to your claim will be the why? or to what end? of that claim. Your reasons cannot, or should not, be unclear wishes, like “because doing so is good.” What does “good” mean in this context? Good for whom? Just as with previous arguments, your reasons are themselves new, smaller claims supporting your larger claim, so you must claim some new specific things.

One of the rationales to take on proposal arguments after some of the other models discussed in this Handbook is the nature of the reasons you ought to offer in support of your claim. Reasons can be offered based in definition, evaluation, or causation.

Supporting Reasons

Reasons of Definition: Just as with the definition arguments, your reasoning here is based on categorization. Generically, a reason from definition would look like “We should do Thing X because doing so treats members of the same category in the same way.” A real-world example would be something like “because gay marriage is simply marriage,” or “because marijuana and alcohol are both drugs,” or “because cheerleading and football are sports.” Here, it might be something like, “because health care is a human right.”

Reasons of Evaluation: As you will have surmised, these reasons are grounded in “what is best” to do. “We should do Thing X because it is the right thing.” Something like, “because free college tuition is a good way to get more deserving people into school,” or “because buying that home is a good investment for the future,” or “because ACME, Inc is the best company for the job.” Here, it might be something like, “because single-payer systems are the most efficient.”

Reasons of Causation: Here, the reasons are based on the outcomes – the “what will happen next” of the proposal. “We should do Thing X because it will lead to these desirable outcomes,” like “because recycling laws will lead to less garbage in landfills,” or “because refocusing police funding will mean more trust and safer communities,” or “because changing pet adoption laws will cause fewer baby alligators to be flushed down toilets.” Here, it might be something like, “because it would result in our state being healthier, more financially stable, and more productive.”

Your proposal can be reasoned entirely from any one of these categories, of course – any one kind will constitute sufficient reasons if you argue it thus — and there is much overlap between them in cases of “Thing X will lead to this good outcome” – which combines cause and evaluation. Again, we are trying to describe the options available to you as the argument creator, not trying to tell you what to do. You will be making rational decisions based on your assignment, purpose, audience, and rhetorical needs.

Once you have articulated your reasons, as always, you must prove they are true by employing proper and thorough grounds. The kind of reasoning you use will at least partially determine how the grounds are constructed because if your reasoning relies on definition, then your “proof” of it will necessitate producing a mini-definition argument; if you used all three examples as above, your grounds will be three micro arguments making up the macro proposal. Is healthcare a human right? Show it through a criteria-match process. Are single payer systems really the most efficient? Show it through criteria-match for the purpose of an efficient system. Would people really be healthier, more financially stable, and more productive? Show it by explaining that if people could get health care, they would, and thus niggling illnesses or conditions would not drag out; the outrageous costs of health care would be moderated; and people who will show up to work and can focus on their jobs will be more productive. Proving your reasons are true supports the value of the proposal.

And as always, by creating reasons and attaching them to a claim, you have created multiple warrants. In the case of our extended example, as a simplification, the warrants would be that “human rights” are good things that should be honored; “efficient systems” are systems worth embracing as they represent the best use of resources; and “health, stability, and productivity” are good ends we should endorse and pursue. If your audience does not accept these assumptions, your argument gets harder. Helping the audience to accept them is the job of your backing, though, is it not? In the extended example, the backing would have to prove or support why human rights should be honored; what is the ethical or legal issue at stake? The backing would have to prove or support why using resources efficiently is wise; no one likes waste, for example. The backing would have to prove or support why health, stability, and productivity are desirable.

As a recap: the grounds prove your proposal will encompass your reasons; the backing demonstrates why those are good things to encompass.

Special Considerations

Just as in earlier modes of argument, there are some special considerations created by making a proposal.

- The increased need for emotional appeal. It is especially important in a proposal argument that your audience feels the necessity of the thing. Your ideal audience is the group or body of people who have the power to enact the thing you are advocating. There is little point in proposing recycling laws to your local PTA – unless you want them to help you agitate for the laws, perhaps. Eventually, you are going to need to take your proposal to the people most directly responsible, and they need to understand the must of it: the time is now! In other arguments, all you are really asking for is agreement; here, though, you need your audience to do something, and that always creates a greater burden; inertia is a real thing in human social relations, too, and objects at rest require greater force to get them moving. For this reason, the proposal may make greater use of pathos than you have up to now. Please be aware this imperative is not permission to get all “abused puppies commercial” emotionally exploitative, but your audience does need to experience the urgency.

- Your audience needs to feel it more because if left to their own devices, people are resistant to change. It is not only a conservative trait to be more comfortable with the familiar, and the preference for the known is widespread. The British political philosopher Edmund Burke had a great quote to this effect: “When it is not necessary to change, it is necessary not to change.” You must demonstrate necessity. If it is just a change “for fun” or “to do things differently” that is the fallacy of the appeal to novelty – not a sound basis for a proposal.

- “Hard to see, the future is,” said Yoda, and right he was. Proposal arguments are complicated by the fact that we cannot know what the future will hold. If we make a change today, what will it lead to? What else might happen in the meantime? You must be able to answer that question at least in part – beyond whatever you are claiming in your thesis, or you will at least have to acknowledge the potential ways this thing could go.

- And how will we evaluate the success of the proposal? Depending on its specifics, maybe we evaluate that way: if we eliminate tuition to increase enrollment, and enrollment does go up, is that a success? What if enrollment goes way up, but a higher percentage of students drops out? Is that still a success because all we really wanted to do was lower the barriers to starting? As the arguer advocating a change, the burden of proof is on you to show how the audience can know if the solution did what it was supposed to do. The harder it is to evaluate, or the longer it will take to see the impacts, there is more work for you to show value.

Exercises

For practice: Identify something you think is a problem at your workplace or with the school.

- Who has the power to make the change that would solve the problem?

- What are some of the other obstacles your idea might face?

- How would you know the problem has been solved; that is, what would be different?

Proposal Phases

For most proposal arguments, there are three elements, or phases, to do the job completely and well. First, as alluded to above, you must prove a problem exists in ways that will convince your audience. You must prove it does exist (unlike the “crime wave” of 2016 that was not), and that as it exists it poses some problems. If a writer is concerned that too few Americans are reading Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s classic novel The Brothers Karamazov, is the audience (students, probably, maybe the Department of Education?) really going to share that concern? The writer needs to find ways to make them. The necessity here will clearly vary quite a bit depending on your problem, but you will find a technique – maybe this is where the pathos comes in, or maybe you appeal to egocentrism in some manner. If Student E says it is too expensive for many students to finish college, and the response is “Well, the world needs ditch-diggers, too,” then E must – through telling stories of determined single parents or explaining the values of a highly educated workforce – explain why we do, in fact, need more college graduates, rather than fewer of them, and that the limited number creates a solvable problem.

Once you have clearly shown the problem is real and a real problem, if you see, then you must offer the specifics of your solution. How will your proposal address the needs of the problem? How will it work? Your thesis cannot be something vague like “Schools need to do more about bullying” or “MACC should do something about food service” or “Congress needs to change some things about inheritance taxes.” You must show the what and the how. This phase is the nuts-and-bolts, the details of any proposal, and while it is not always the most fun part to explain, it is vital to your project’s success. It is true that practical proposals might lend themselves more easily to this step. If you want your hometown to build a traffic circle, you will be able to name streets, detours, businesses affected, times of day the intersection is busiest, and so on. For policy proposals, the scale of the thing might create obstacles, but you must do your best. If you are proposing a Universal Basic Income, how will it be paid for? Who will it be paid to? How basic? Demonstrating to your audience the finer points enhances your ethos and pre-empts much rebuttal. Leaving too many questions about “how would it work?” is a sure way to lose the skeptical audience.

At this stage, you have shown the problem and an answer to the problem. Right now, your situation is rather analogous to the stage of the causal argument wherein you have proven X and Y, but you must still show how X created Y. For this proposal, this third step is often called justification, and is the moment when you explain how your plan will truly solve the problem through your reasons. Anybody can notice a problem and craft a cockamamie scheme, but the payoff comes when the audience sees how it will all work out. This effort is how you convince your audience the proposal is worth the changes, and it is how you pre-empt some elements of rebuttal. This step is probably most of your argument: how seriously we need to solve Thing X, how there will be struggles but they will be worth it, etc. Your good idea will not explain itself, so you must justify it to your audience.

Proposals, like the other modes we have covered, create problems particular to that mode. If you would prefer to think of these questions as addressing special rebuttal concerns, go right ahead, as rebuttal might be the best place to address them, if you have not done so already through the normal course of your argument.

Your audience will first ask, “Is this really a problem?” If it is not, or you have not shown that it is, you will fall at the first hurdle because if there is no problem, there is no need for a proposal to fix it. Ideally, you have answered this question in phase one; you must at some stage, at any rate. Your audience will then ask, “Will your proposal really work?” If you have used good justification, you may not need to do too much here, but at some point you must have demonstrated that it will, in fact, work. Your audience will ask “Couldn’t we solve the problem more simply some other way?” Remember, people want easy, so if your solution is incredibly convoluted or complex, the audience’s enthusiasm will wane. There is an old (possibly apocryphal) story about a big truck getting stuck in an underpass. The city engineers – being engineers – started planning on bringing in the heavy machinery, diverting traffic, and taking the underpass apart to free the truck. Then a young girl in the crowd that had gathered to watch said, “Why don’t you just let the air out of the tires?” Problem sorted. For your argument, you must show that a) there is no easier way, or b) the easier way will not really fix the problem or will not fix it as well. Duct tape is a solution to many problems, but even duct tape has its limits. Your audience will ask “Is it practical?” I had a friend who often said he had the solution to all problems of sexism, race, and class; the first step was for us to evolve into some sort of flying creatures. As a first step, that is a doozy. No matter how good your idea is, if it cannot reasonably be done, it will not be adopted. There are two sub-problems here:

1) The proposal would work, but it is too expensive. You may remember shooting rockets full of garbage into the sun?

2) The proposal might create other, worse, problems. Fun story: The Rolling Stones held a free concert in Altamont, CA, in December 1969, but worried about crowd control, so they let the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang volunteer to handle security. As you can guess, this went very badly, and a man was killed by the HA that night. In one of my favorite childhood books, a child gets a mouse out of his house by bringing in a cat; the cat is annoying, so he brings in a dog; the dog has fleas, so he brings in a pig; then a lion; then an elephant; to get rid of the elephant, he brings back the mouse. Make sure your proposal will not just make matters worse.

Finally, your audience will ask “What don’t we know?” Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was famous for talking about “known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns” – things we do not even know we do not know. Some of that is inevitable in a proposal argument (no one can see the future, right?), but you need to show your audience you have a least tried to cover all the bases and imagined how this may play out.

If we want to look at the overall organization of a proposal argument, it might look something like this:

Examples

Introduction

(assuming the classical argument model)

- Exigency/catchy opening – if the topic is the expansion of Medicare, maybe begin with a story about people who need the protection of health care coverage but fall through the cracks of all the existing systems.

- Explanation of context – here, it might be a question of how the problem has arisen, or some brief history.

- Thesis: “The state legislature should expand Medicare to cover all Missourians, effectively creating a single-payer health care coverage for our state because health care is a human right, single-payer systems are the most efficient, and it would result in our state being healthier, more financially stable, and more productive.” ** NOTE: Your audience needs to be part of your claim and cannot be something vague like “We need to . . .” or “The US should . . .” Who is “we”? Is “the US” really Congress? Be as specific as possible.[2]

- Make transition.

Body

- Prove the problem is real, and it is a real problem. You would discuss how the current health care and insurance system is expensive, inefficient, and not really all that effective even when it works. You would show how private health insurance tends to rise by double-digits year over year, and then you would argue that is simply not sustainable forever. People who are sick or impoverished by the treatment of their illnesses are not likely to be the most productive members of society, and that results in a significant loss of capacity and revenue for the state. The system we have is not working well, and here is the evidence, etc.

- Provide the specifics of your proposal. Now you explain how Medicare works and how Medicare expansion would work. One of the first things you would have to come to grips with is how to pay for what would a very expensive proposition. You can argue that the state – and its citizens – are wasting a lot of money now, and maybe those costs can be recaptured and repurposed for the Medicare expansion, but you may also have to raise corporate taxes or taxes on the 1% or something to pay for it; what will your audience value or accept? Would the state pay doctors and other carers directly? Would the state provide a subsidy for the citizens to pay for their health care? How would it look? Do not be vague, or problems will abound.

- Justify your proposal by showing the mechanics of how it will solve the problems you detailed in point #1 above. Define “human right” in a way that encompasses health care, evaluate the efficiency of single-payer systems, demonstrate that having health care covered would cause the population to be healthier, more financially stable, and therefore more productive. This phase will incorporate most of your grounds and backing.

- To the extent you have not already done so, address rebuttal. Be honest about cost and potential drawbacks, like increased bureaucracy, perhaps? What do critics of a single-payer, Medicare-like system say? What strengths must you simply acknowledge, but what weaknesses or flaws can you point out? Be sure to frame the rebuttal so that it strengthens your argument.

As a generic or hypothetical matter, opponents could object to the existence of the problem (“it is not that bad”); they could argue that your reasons are not worth the cost, inconvenience, etc.; they could argue your proposal will not fix the problem; they could argue the problem could be fixed some other way. As you construct the confirmatio portion of your argument, think about ways to head off or anticipate such objections. As you construct the confutatio portion, take the objections you have found seriously, but explain them away.

Conclusion

- Once again, as always, find an interesting way to summarize what the readers have learned from your argument.

- For a proposal argument, suggesting a next step is the best, most logical way to go at this point. Since your audience now recognizes a problem and how to solve the problem, you need them to move on the problem. Urge action. Constituents should contact their legislators; legislators need to make MOMedicare a priority, and they must begin debate on it at the earliest opportunity.

- End in some vivid way designed to stick in the readers’ minds: “Our state has been muddling along in a haphazard health-care haze, and we now have the opportunity to get on the road to recovery!”

- Unless your teacher wants you to write a proposal argument first. ↵

- And it might go without saying, but a serious proposal argument cannot be something like “We – literally every single person – should be nicer to our neighbors and to strangers.” That is a public service campaign, not an academic argument. ↵