3

What Argument Is . . .

If you feel like a bit of silliness, you should take a moment (about four minutes, really) and watch “The Argument Clinic” sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus; you might be able to find it on YouTube. As a word of warning, it is a clip from an early ‘70s TV show, so you will have to simply overlook the furniture, the haircuts, and the fashion.

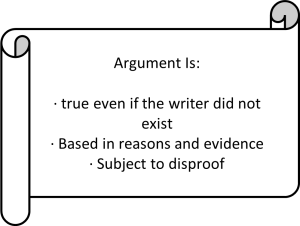

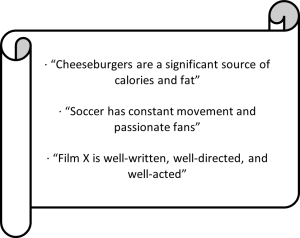

Okay, done? Wasn’t that funny? So why watch it? Despite the absurd premise, this sketch does provide some useful insights as we get started. First, to argue, I must take up a contrary position to yours. This precept is our basis: argument requires disagreement. Thus, you must avoid topics about which no reasonable person would disagree, so nothing like “pediatric cancer is bad, and we should try to cure it” or “eating disorders are bad for a person’s health” or “children shouldn’t have to play around land mines” or “meth makes bad breakfast food,” or “Led Zeppelin is the greatest band in rock music history”[1] etc. You must be able to imagine an otherwise reasonable person who might disagree with your initial claim. We will discuss how you might conceptualize “reasonable” in Section V, in “The Argument Spectrum,” so do not lose track for the moment.

Second, argument is a series of statements in support of a definite proposition. Most of the time, this proposition is called a thesis, and the series of statements are the evidence and the reasons the thesis is true.

The next thing we can learn from the skit will come in a moment, but while we are still discussing the positive parts of what an argument is, the third element is that an actual argument will  always include the claims of the opposition; these will be addressed, discussed, and dealt with, but it is to be understood that these counterarguments are explained in the service of your argument. We will discuss this piece in more detail in Section VII, on “The Toulmin Schema.”

always include the claims of the opposition; these will be addressed, discussed, and dealt with, but it is to be understood that these counterarguments are explained in the service of your argument. We will discuss this piece in more detail in Section VII, on “The Toulmin Schema.”

Fourth, genuine argument can come in multiple forms, and it can be explicit or implicit. “Explicit” here means you just come right out and say it: “The death penalty is wrong!,” for example. Most of the argument you will do this semester will be of the explicit sort. But maybe not all of it, and “implicit” means that the argument is only implied or suggested. A movie or song might make a strong case against the death penalty without ever directly expressing a claim – maybe an extended example of someone wrongly convicted and executed will do the work. Implicit argument is often heavy with emotion or it needs to be interpreted.

Fifth, you should remember that we are not talking about “winning” or “losing” in the courtroom sense, so you should probably abandon any sense that you will create a magic bullet argument that puts an end to the contrary views once and for all. The German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) developed a theory of history he called “the Dialectic.” In this theory[2], a dominant mode of thinking at any given moment is called a “thesis.” The presence of this thesis necessarily creates its own opposition, which he called the “antithesis.”[3] The work of the two forces together then leads to “synthesis,” or a melding of the two. That synthesis then becomes the new thesis, which will eventually produce its own antithesis, and round and round we go. Hegel believed that all of this was leading somewhere good: the end of history when all our problems would be solved, but he was a product of Enlightenment Thinking.

What is this wordplay got to do with us? Think of your argument as a kind of thesis (or an antithesis, if you would prefer); your ideas will be taken on board by the opposition; they will respond; you will respond to their response; and round and round we go. Does this sound rather depressing and pointless? Never fear. Unlike History, which does not really have a beginning or end[4], the argumentative process does lead somewhere; eventually we do get to the point at which most of the contrary arguments have been dismissed or dealt with. Think of all the things once passionately argued about that we do not argue about anymore: independence from Great Britain (yes), slavery (no), votes for women (yes), the metric system (no, apparently), etc., etc. Therefore the argument you write will be a moment frozen in time, but the contribution it makes to the topic is part of the ongoing process. Your work, then, is both static and dynamic.

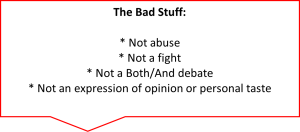

. . . and What It Is Not

Let us go back to the Monty Python sketch for a moment. In the first room the client entered, a man sitting behind a desk shouted abuse at him, including the deathless finale of calling the client a “vacuous, toffee-nosed, malodorous pervert.” Once they get the misunderstanding cleared up, the client goes into the right room, the argument room. What is argument not? In the first place, argument is not abuse. Calling people names, belittling their qualities, insulting their IQ, their fashion sense, their family three generations back, none of that is legitimately argument. Do not make up derogatory nicknames; do not suggest that traits like gender or race or ethnicity or age are relevant factors if they are not; do not ascribe nefarious motivations to people (“She’s evil, I tell you!”) just because they disagree with you. You are better than grade-school insults, and your argument should be, too.

In some ways, of course, the list of things that argument is not is endless – it is not a recipe, it is not a travelogue, it is not a biography, it is not an ancient formula for reanimating the dead, etc., etc. But there are some common mistakes that stu dents sometimes make, so we will focus on those errors.

dents sometimes make, so we will focus on those errors.

Second, as the opening dialogue of this handbook tried to make clear, sometimes people do not want to get into an argument because they think it is unpleasant to fight with friends or family (or even strangers on social media). But remember that we want you to argue; argument in the intellectual sense is psychically satisfying and rewarding. It is like solving a riddle or puzzle or figuring out the answer to a problem that has been plaguing you. So do not fight; do not yell or merely contradict. That is not argument.

You may recall in the above discussion that genuine argument must take the opposition into account, and so it must, but not in the sense that you must be somehow balanced. Argument is not a listing of comparative advantages or disadvantages, or structured like “first this, but, on the other hand, this also.” Therefore, third, argument is not a sort of Both/And debate where the writer stays aloof and gives equal time to both sides of the proposition. You are to have a clear argumentative point to make, and you bring in the opposition to dismiss or weaken their claims and thus strengthen your own. You must represent their view fairly, but only in order to enhance your goals. In many high school forensic contest formats, the Lincoln-Douglas Debate may sound like it would approach argument, but it is usually structured so that Student A argues one position in the morning and its opposite in the afternoon. What the student thinks probably does not factor in all that much. That is a fine exercise in sophistry, perhaps, but it is not the kind of argumentation you will undertake, in which you have adopted your claim because it matters to you or you believe in it for some set of reasons you can articulate.

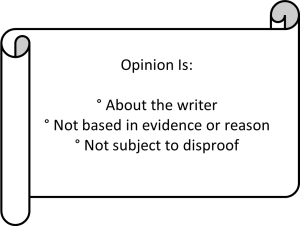

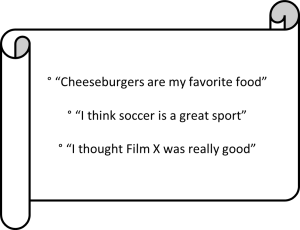

As our fourth point, we need to dispel the idea that argumentation is based in opinion. It is not. At this stage, we should spend a moment and define “opinion.” No one at the college is interested in stifling your opinions or in making you change them, and that is because opinions, properly understood, are your personal thoughts about your subjective feelings.

Opinions only reveal information about the writer’s preferences, not anything true about the state of the world. If the writer should blink out of existence, those preferences also disappear, and the wider world is unchanged. At the same time, if pressed, the writer of an opinion cannot justify or explain the preference any way beyond “that’s how I feel about it.” The writer’s feelings are not grounded in evidence or may not be explainable any other way. My favorite color is red, but I cannot give you “reasons” for that beyond “I like it best.” As that would be arguing in circle, it cannot be the basis for arguing “red is the best color.” Remember that since argument requires conflicting assertions, someone would have to be able to counter with “red is not the best color; blue is,” but how would you begin to prove such a thing?

Suppose a writer claimed that bologna was her favorite sandwich meat. Now suppose you followed that writer around for a month and never once saw her eating bologna; would that prove she was lying? No, clearly not. Maybe she is on a diet, or she lost a bet and cannot eat her favorite food for six months, or she has developed an allergy. If a claim cannot be disproven, it is probably an opinion and not the basis for an argument.

Sometimes writers or speakers of a certain sort will tack on “in my opinion” precisely to avoid response or rebuttal – they want the intellectual irresponsibility of not having to articulate a defense of what they are about to express. This cannot be a sound approach, clearly.

It is odd, admittedly, that the inability to disprove a claim is an indication of its weakness as an argument. “Surely,” the ambitious student may say, “if you can’t prove I’m wrong, then my argument must be right, and I win!” Unfortunately, that means your claim was not really viable in the first place; such an argument is an embodiment of the “appeal to ignorance” fallacy we will learn about later. Sorry – you are going to have to use proof and evidence, rather than just saying “because I think so.”

- Okay, your mileage may vary with that claim, but still . . . ↵

- Again, this is simplistic: like I said, take a Philosophy class! But it’ll be broadly useful enough for our purposes. ↵

- It looks like it should be pronounced “anti-thesis,” but it’s usually pronounced as “an-tith-uh-sis.” ↵

- Just points before and after when there is no one around to record it. ↵