4

The Thesis

Where to Start

Now that you have an idea of what argument is or should be, and how to read others’ arguments, it is time to work on creating one of your own. The part of the work from which all other parts grow is your thesis. This is a word you have read several times already, as it is hard to write about argument without using it, but as you may think of it in different ways, what does it mean, exactly?

Your thesis is a one- or two-sentence summary of your whole argument. It boils down your point to something succinct and clear. It is likely you have dealt with theses before, so this should not be entirely new, but they are central to a clear argument, and thus need as much practice as possible.

An ideal thesis has several defining traits, most of which mirror the larger argument concerns addressed above. So, the thesis must address a manageable problem, it must be a problem we can hope to answer through research, it must be disputable, it should be usefully predictive, and it should be phrased as a declarative statement and not as a question.

- If your thesis does not address a problem, it will not rise to the level of needing attention from your audience; it has failed the “so what?” test. Keep in mind that an argument is not a matter of merely personal expression, so it is not a matter of being a problem to you. “My partner should be more willing to take out the trash” is not a workable thesis because the readers are likely to say, “Uh-huh. Good luck with that.” It must be some issue your readers can be made to care about: “Americans should eat more turnips” might be a start if you can find ways to compel interest in increased turnip consumption. More usually – but not always — you will start by addressing some recognized problem. Further, that problem should be the kind of thing you can adequately cover in your standard essay-length treatment. “I am going to solve the problem of world poverty” is admirable but too ambitious for the scale of argument you need to produce. “We are going to reduce poverty in Missouri by doing X, Y, and Z” is more likely to lead to a productive argument.

- There are any number of potential problems it might be fun to argue about, but the argument will be an exercise in futility and wasted time unless the matter can be taken further. “We should prepare ourselves for alien invasion” might seem like it addresses a problem, but how would a person research evidence in such a case? It is highly unlikely that alien invasion will have any comparable historical analog: it will not be like the Vikings, or the Mongols, or the colonial powers. So where should the would-be world saver begin? How to repel methane-breathing viruses? Is that going to be possible? No, not in any useful way. It might be possible to get an audience to agree with the premise that being prepared is better than not being prepared, but then what?

- Preparing for alien invasion might also be problematic because a thesis needs to be disputable or rebuttable. As explained earlier, there must be conflicting assertions. What sort of reasonable person would argue that being unprepared is preferable? A person might very well argue we should not bother because we have no idea how to begin, or because it would cost too much, or because we should seek to live in peace with all alien lifeforms, but those assertions don’t directly address the thesis. The requirement of disputability means you must avoid subjects or topics that may look like argumentative claims but are not, really. “Seatbelts save lives” is well-established statistically, historically, experientially, and in every other meaningful way. Just because you knew a guy whose cousin Earl in Florida got thrown clear and was saved precisely because he was not wearing his seatbelt only proves that very few things are 100%, but you can contrast Earl’s experience with the thousands of other people killed every year who were not buckled in. “People should stop drinking and driving” is not arguable because even though people do continue to drink and drive, there is no pro-drinking/driving side to argue. No reasonable person is suggesting there may be perfectly valid reasons for an individual to get drunk before taking up the car keys. People continue to drive drunk because they are drunk: they are not thinking clearly or logically, so clarity and logic are meaningless to them. Pick a thesis someone who is not drunk can disagree with.

- A good thesis is also one that previews to the reader some sense of the organizational scheme of the essay. Do not be vague with a thesis like “There are many things Missouri could do to reduce poverty.” What are those things? A thesis will usually include the main points/reasons/events in the order in which they will be addressed. “We will reduce poverty in Missouri by raising the minimum wage, expanding Medicare, and investing in roads and infrastructure” tells the reader what the main points are and what will come first or last.[1] Including all that material in a single sentence might sometimes cause the sentence to get rather wordy and convoluted; this is why a thesis may be in multiple sentences. Wise students will learn their teachers’ preferences for thesis clarity and concision.

- Your thesis should also be a simple declarative sentence. You are trying to suggest an answer to the problem you are taking on. You are not merely posing the question. “Should we do something about welfare reform?” is not a thesis, although it might be the question the thesis will answer.

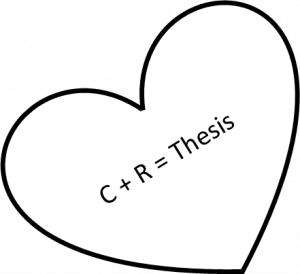

In addition to all those traits, a good thesis has two parts; you may have noticed this already. These parts are called the “claim” and the “reasons.” The claim is the assertion you are making about the nature of the world (“We will reduce poverty in Missouri”) and is the base idea. The reasons[2] are the explanation of the why or the how that justify the claim (“How will we reduce poverty in Missouri? By raising minimum wage, expanding Medicare, and building better sewer systems”)

While it is possible to link your claim and reasons in any number of ways, using the word “because” creates a clear logical relationship between your elements. Indulge me for a moment while I tell a brief story to illustrate this point. When my oldest daughter was little, probably about four, she would often – as most kids do – explain herself by saying “because.” “Why do you want this ball instead of that ball?” “Because.” Okay, so one day I picked her up from daycare and she said to me, “We should go get ice cream.” I asked why we should go get ice cream. She said “Because.” Never missing a teaching opportunity, I said “’Because’ is a not a reason; it is a word we use to introduce our reasons. So why should we go get ice cream?” She thought for a second and said, “We should go get ice cream because you love me and want me to be happy.”

Well, it is true I love her, and it is true I want her to be happy, so she gave me good reasons following the word “because,” leaving me with little choice but to take her for some ice cream. “Because” works – use it when you can! As in, “You should use the word ‘because’ [claim] because it makes the logical connection between the claim and reasons clear [reason].” We will return to claims and reasons soon.

—–

There are a few further refinements about what makes a good thesis we need to cover before we continue.

True Thesis v. Pseudo-Thesis

A true thesis is one that will lead to an actual argument; that is, it will meet all the criteria covered so far. For example, “Smoking while pregnant is child abuse,” or “MACC has an excellent teaching and learning environment for a community college,” or “Our taxation policies cause income inequality,” or “We should elect Candidate X.” These are all disputable and thus can be usefully answered.

A pseudo-thesis, though, is not going to lead to a real argument (hence “false”). A pseudo-thesis is something that people may very well disagree about, but there is no way to go forward and attempt to settle the question. This can be caused by a lack a shared assumptions – if the person you are arguing with thinks cancer is a good means of population control, it is going to be very hard to agree on what to do about cancer funding or research. A pseudo-argument may also grow from impossible to quantify questions, like what makes a person beautiful. There is a reason we have the old expression “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Our feelings about that issue are not subject to reason or explanation, and thus are closer to opinions, so those kinds of judgments are not likely to lead to productive argument. The same is probably true about many artistic or aesthetic preferences (“What makes this song so awesome?”).

What you will learn to do is to make distinctions between what we can and cannot argue about. We may not be able to settle the question “Is Van Gogh’s Starry Night a beautiful painting?” but we may be able to argue the question “Is a quilt of Starry Night a work of art?”

Question Thesis v. Answer Thesis

One of the other common flaws of a thesis occurs when a would-be arguer offers some claim that can simply be answered by resorting to available facts. “The United States incarcerates a higher percentage of its population than any other industrialized country” can be settled by looking a table showing the percentages. Important note: The “ease” of this answer does depend on our agreeing what an “industrialized” country is and our agreeing that the source of the data table is authoritative and reliable; this agreement is why shared assumptions matter. A thesis that raises questions makes a good argument, while simple answers do not.

An “question” thesis, then, is one reasonable people may dispute; it is often framed as an attempt to explain something to people[3] or an attempt to change their minds. “Should we increase inheritance taxes” is a question that could lead to an issue (taxation) thesis and an argument because it does not have an “answer” that could be looked up in some responsible source. Reasonable people may have different answers. In fact, maybe we should spend a moment asking what makes a person reasonable.

- The pattern of the main points is probably determined by your rhetorical goals: maybe these three are arranged by order of importance, for example. Refer to the Reading, Thinking, Writing Handbook for more guidance on arrangement strategies, or ask your teacher. ↵

- A reason is also sometimes called a premise; in any event, most reasons are themselves further claims, and it’s just a feature of argument that it’s claims stacked on claims; it’s claims all the way down . . . ↵

- Remember the translation of “arguere” – to make clear; to explain ↵