5

The Audience

Audience Considerations

Here is a foundational premise: Good writing is about the reader, not the writer. For us, this means an argument is not a means to express what we, the writers, think, but it should be what the readers should think. The point of the argument is for their benefit.[1] Your audience is crucial to the success of your argument; you must take the audience into account and adjust for them. But we are not pandering to the audience – an important distinction. There are several elements to employ to ensure the audience is a key part of our argument.

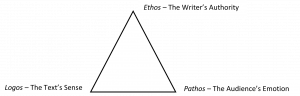

The Rhetorical Triangle

As with many of the argumentative concepts in this handbook, the Rhetorical Triangle comes to us from our friends the ancient Greeks, thus the terminology. The Greeks did love their symmetry, and the triangle seemed to capture something essential about the relationship of the parts to the whole. All these elements need to be balanced to produce the ideal argument; it is not like ethos is at the top because it is “most important” – something had to be at the top, so there it is.

Ethos

* Ethos is the measure of how much authority or expertise the author brings to bear on the issue. If the issue is the US Presidency, and the writer is Doris Kearns Goodwin, she is going to have a great deal of built-in ethos because she has written a dozen books on presidents and US history. She has earned the right to be given a certain benefit of the doubt – she is an authority, as we discussed in the opening section of the Handbook. Not only has DKG written many books, but they have been widely reviewed and discussed; sometimes her conclusions have been questioned or revised, so she is taken seriously by other historians; and she is often called upon to offer historical perspective in public fora like panel discussions, news programs, and the like. It is not the case that she is the sort who has self-published several rambling manifestos popular in the depths of the internet. She has spent her professional life achieving a degree of knowledge that gives her solid ethos.

Well, most of us are not Doris Kearns Goodwin, so what is to be your strategy if you do not possess the necessary ethos? Keep in mind that for some topics, you may very well have a great deal of authority to apply; if you are writing about some condition you have had your whole life, the audience is likely to grant you know what you are talking about and believe you. If your life experience, job experience, etc., have, in fact, given you something authoritative to say on the issue, then you need to be able to explain that in a way your audience will understand and appreciate. If, on the other hand, your expertise consists of reading a tweet about an article about the issue, the audience is not going to treat you like an expert. This is one reason why qualifications like “I read on the internet once” are not suitable for college-level writing. Even if you do have special relevant knowledge, keep in mind that by yourself you are not sufficient to support an argument. DKG does not write books without resorting to historical materials, and neither should you. Feel free to bring your ethos to bear, but it should be part of the whole, and not the whole.

You have probably already guessed what you must do: you must borrow other writers’ ethos and do research. When you quote experts and authorities, you are putting on their ethos as your own argumentative armor. Obviously, this works better when the ethos of your sources is widely recognized or clearly apparent in some way. If you spend the whole essay quoting material only known in dark corners of the internet,[2] that will hurt your ethos in the readers’ minds. In the section on research, we will return to the idea of how to make sure you are using sources with solid ethos.

Aristotle explained that ethos was the function of “the good [person] speaking well” – that your ethos was a function of character and competence. Character may be less of an issue in a world wherein we do not know everyone, but it does highlight that a given person might have strong ethos for one audience, and low ethos for another. Think of some deeply polarizing figure – maybe you can work up some current examples – and now imagine that person walks into a room with a legitimately great suggestion about addressing our energy pollution needs. The people who like this figure will say “Yeah, good idea,” but the ones who hate this person will probably say “No way, man, no way” – at least at first. They may come around eventually, but it will take more work to get them to overcome their sense of ethos. For the time being, your character is not an issue,[3] but it may matter for the sources you choose. Competence is an easier matter because that is more within your immediate control: do good work. Face it, if this Handbook were littered with solecisms, typos, outright false statements, and childish language,[4] you would not take it as seriously as you would if it were done at a high level. The same thing applies to your writing: if you misspell the name of the novel character who is central to your analysis, your ethos suffers. If you misuse commas or apostrophes, your ethos suffers. If you refer to your sources by their first names, as though you were old school chums, your ethos suffers. If you cannot follow the guidelines of MLA citation, your ethos suffers. Thorough revision, editing, and proofreading are your best assurance of displaying your competence.

Logos

* Logos is the degree to which your argument makes sense and is sound. As you may already know, “logos” is Greek for word, but it includes additional connotations, and if it reminds you of “logic,” so much the better. Okay, let us suppose that Doris Kearns Goodwin is doing our writing, so the ethos is locked down. But also suppose that her working thesis is “Barack Obama was a good president because he played basketball.” Huh. Well, we have a clear claim, and we have a clear reason. The thesis seems arguable, but how would one begin, exactly, when . . . it makes no sense. Your critical thinking skills should tell you that playing basketball (or golf, or tennis, or building ships in a bottle, etc.) has nothing whatever to do with the quality of one’s presidency. A president has many functions to perform, but participation in sports is not one of them. If the presidency does not move you, how about “We should recycle because puppies are so cute” or “Social media is causing the decline of Western Civilization because fewer cookies are being baked.” Admittedly, few arguments are going to be so bizarrely inappropriate, but what you need to be aware of here is that you are using the best evidence and that you are making the connections between your ideas as clear as possible to the audience.

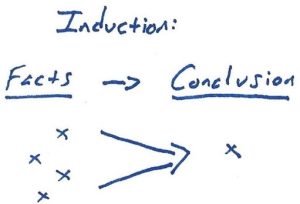

There are many methods of making sense, or reasoning, in an argument. One of the most common is called Inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning is the tactic of observing the phenomena of life – the stuff happening – and drawing conclusions from those facts. If a Person R notices that Person Q’s favorite writer is Stephen King, favorite TV show is The Walking Dead, favorite movie is The Exorcist, and favorite musical genre is Swedish Death Metal, Person R can reasonably conclude that Person Q loves horror. If Person W notices that women earn less than men for comparable work; women make up 50% of the population but less than a  conclusion” width=”300″ height=”204″>third of political office holders; women often have double-standards of competence, behavior, and attractiveness that men do not have; and that single women with children are often below average in financial security while single men with children are often above average in financial security, Person W might reasonably theorize that America is a sexist society. If Person D notices that America has a lower life expectancy, a higher infant mortality rate, less ability to bargain with drug companies to adjust costs, and spends much more per capita on health care than any country with national health services, Person D can reasonably suggest that socialized medicine might be a better system than whatever we currently have.

conclusion” width=”300″ height=”204″>third of political office holders; women often have double-standards of competence, behavior, and attractiveness that men do not have; and that single women with children are often below average in financial security while single men with children are often above average in financial security, Person W might reasonably theorize that America is a sexist society. If Person D notices that America has a lower life expectancy, a higher infant mortality rate, less ability to bargain with drug companies to adjust costs, and spends much more per capita on health care than any country with national health services, Person D can reasonably suggest that socialized medicine might be a better system than whatever we currently have.

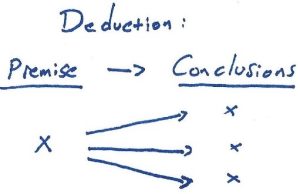

The sort of “flipside” to induction is called Deductive reasoning, and Sherlock Holmes is probably the most famous practitioner of this method. Deduction is the tactic of beginning with a premise, precept, or theory, and then applying it as situations arise. Holmes’s famous formulation was “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” From this foundation he would proceed to solve crimes. Since we are not likely to be great detectives, for the average  conclusion” width=”300″ height=”194″>arguer, deduction would normally take of the form of applying our premise whenever a relevant question or dispute would arise. If we know that mammals are warm-blooded, then we can assume that even oddballs like the platypus are probably warm-blooded. If Timmy tosses a ball to Tommy and Tommy catches it with his right hand, we would deduce that Tommy is right-handed, since we understand that people tend to catch objects with their dominant hand.[5] If a friend knows you like Rock Band X and knows Bands Y and Z sound like X, your friend might deduce that you would like Y and Z.

conclusion” width=”300″ height=”194″>arguer, deduction would normally take of the form of applying our premise whenever a relevant question or dispute would arise. If we know that mammals are warm-blooded, then we can assume that even oddballs like the platypus are probably warm-blooded. If Timmy tosses a ball to Tommy and Tommy catches it with his right hand, we would deduce that Tommy is right-handed, since we understand that people tend to catch objects with their dominant hand.[5] If a friend knows you like Rock Band X and knows Bands Y and Z sound like X, your friend might deduce that you would like Y and Z.

Other common kinds of reasoning, like categorical, causal, or analogical, will be discussed in their relevant sections.

Pathos

* Pathos – to come back to puppies – is the appeal based on emotions. Please notice that your arguments should include some awareness of the value of emotional pull – but you must resist the easy and very present temptation to substitute emotion for reason or authority. If you want your readers to feel the human toll of a given refugee crisis, yes, include some of the tragic stories of lives lost and families separated. But your essay should not simply be a catalog of these stories. That sort of accumulation is not an argument. The responsible use of pathos understands that the audience needs to feel – as well as think. It cannot be all feeling. But pathos is often abused, precisely because it so powerful and easy to do. As evidence of its ease, you might look to any country music song that wants to pull at your heartstrings. A couple mentions of beautiful children, mama, and summer afternoons will hit all the feels. The pathetic appeal is why those awful commercials of abused animals are still running – they  must work. If people see enough shivering dogs in cages, their feelings will take over, they will whip out the checkbook and send a quick twenty bucks to keep little Rover from being sent to puppy death row. What those people are not doing is stopping to think, rationally, about the situation: “Hmmm. Will this money go to the dogs’ care, or toward making more of these commercials, or to the CEO?” Too much pathos short-circuits our proper consideration of the organization’s ethos, maybe. The same emotional appeal occurs when cute kids are used in commercials, or when performers on American Idol want to share their sob stories; how well someone sings is not a function of how difficult the journey has been, but then it is a TV program designed to lure eyeballs – it is only superficially a talent contest. But, to repeat, it is easy to make people feel: describe a flag burning, or a police beating, or a sick child, etc. What is harder to do – and therefore more important – is to make people balance the feeling with thinking. If you take the Rhetorical Triangle seriously, you will strive to create that balance.

must work. If people see enough shivering dogs in cages, their feelings will take over, they will whip out the checkbook and send a quick twenty bucks to keep little Rover from being sent to puppy death row. What those people are not doing is stopping to think, rationally, about the situation: “Hmmm. Will this money go to the dogs’ care, or toward making more of these commercials, or to the CEO?” Too much pathos short-circuits our proper consideration of the organization’s ethos, maybe. The same emotional appeal occurs when cute kids are used in commercials, or when performers on American Idol want to share their sob stories; how well someone sings is not a function of how difficult the journey has been, but then it is a TV program designed to lure eyeballs – it is only superficially a talent contest. But, to repeat, it is easy to make people feel: describe a flag burning, or a police beating, or a sick child, etc. What is harder to do – and therefore more important – is to make people balance the feeling with thinking. If you take the Rhetorical Triangle seriously, you will strive to create that balance.

Audience-Based Reasons

Recall that a “reason” is a kind of sub-claim used to support your primary claim. “Ice hockey is the coolest sport because it has the coolest jerseys” uses cool jerseys as a reason to believe ice hockey is cool. The reasons that you use will be stronger – meaning more likely to lead to acceptance by your readers – when those reasons are grounded in the values of the audience you are addressing. What you must do is think about what your audience needs in order to be moved.

Please note this lesson does not, emphatically, ask you to be some sort of sellout who just tells the audience whatever they want to hear. We often mock politicians for some version of this: If Candidate A goes to an elementary school and says “There’s nothing more important than children,” and then goes to a factory and says “There’s nothing more important than the working men and women of America,” and then goes to a senior center and says “There’s nothing more important than our senior citizens,” that candidate would be roundly mocked and rightfully criticized for a certain elastic sense of “most important.” You will be better than that. It also does not mean changing the topic itself because an audience may not want to hear it. If you are writing to workers at a coal mine about the need to move away from carbon-based sources of energy, sometimes people simply need to hear things they will not like, and you will have to tell them. This lesson is about the reasons that you offer, not the claim you take on.

Exercises

For practice: Try to come up with some audience-based reasons for the following scenarios.

- You are advocating for English as the national language to a group of immigrants.

- You are advocating for a school bond issue to a couple with no children in school

- You are advocating for an extended essay deadline to your Comp II teacher

What are some of the assumptions you might start with about your audiences’ values? How would you address those?

Essentially, then, your claim is set, no matter who the audience is. That is the issue you think is vital enough to argue about, so do not shirk. For the sake of clarity, to repeat: using audience-based reasons does not mean you are trying to fool anyone or weasel your way out of anything. You are adapting to your audience – which is good because, as said before, the audience is the point.

Clearly, this approach will work best if you know something about the notional ideal audience your argument creates. Think about who you are writing to. It is easy to simply rely on those values we have already as writers, but will those ideals matter to the audience? Writers who assume the audience is simply an extension of their own beliefs often commit errors or ground the reasons in faulty logic. As an example, if a writer says, “We know the Bible tells us how to handle this situation,” that basis may move the writer, but it will only move the audience if they already agree with the Bible’s validity – and if they do, how much room for disagreement is there likely to be? Such disagreement might exist, of course; members of in-groups often have serious disputes (like the Thirty Years’ War mentioned in the opening), but as a writer, you must know when – or if – your audience would productively share your values. You cannot merely assume they do or assume everyone is basically like you: they are not.

Imagine a classroom scene: The teacher says to the Comp II students, “You should all work very diligently on revising and editing your arguments.” So far, so good, yes? We have a claim, and while it is probably not too arguable,[6] we shall set that aside for the moment. The students might have a good idea of why they should do as the teacher asks, but just to be thorough, Student S asks “Why should we work diligently?” What S is asking for is a reason. What if the teacher then says, “You should all work very diligently on revising and editing your arguments because it will save me a lot of time when grading”?

Are the students likely to say to themselves and one another, “Yes, our most important concern in life is making sure that Professor P has an easy time of grading”? No, they are not likely to say that. And why not? Is it because they are bad and selfish people? Of course not, but they are people, and all people, to some extent, have a natural self-interest. All audiences are going to ask “Why is this relevant to me? What is in it for me?” That tendency is called egocentrism, and it is neither good nor bad, but it is a fixture of dealing with real audiences. It is possible, surely, for egocentrism to become mere selfishness, just as it is possible for people to set aside all personal concerns and behave selflessly. Your default assumption should be that people are basically good and curious and want to know what is in it for them. So you have to tell them – that is the psychology behind audience-based reasons.

It is possible to imagine that Professor P is so wildly popular that students in those classes never want to cause any disappointment or dismay to a beloved teacher, and they will work hard to make sure P’s weekends are unencumbered with too many comma splices. It is more probable, however, that – even if the students are well-disposed to P – they will still say to themselves “Why is it my concern that the essays take a long time to grade? That’s what you signed up for, Prof, when you went into teaching; it’s part of the gig, so stop whining.” Professor P has failed to use a sufficiently audience-based reason; the reason offered was much more “writer-based.”

Professor P, though, is undaunted, and tries again: “You should all work very diligently on revising and editing your arguments because you will suffer if you don’t.” Hmmm. Well, people, certainly self-interested people – which is all people – do not want to suffer. Suffering is bad and should be avoided, yes? But we hope it is not too much of a shock to you to learn that threatening your audience is not really a sound long-term strategy for getting them on your side and making them sympathetic to your argument. It is not persuasion to say to a person “Do this thing or I’ll break your arm.” In fact, it may be a crime. In any event, this approach is dubious. Now, it may be true – if the students get low grades, maybe they lose scholarships, are forced to drop out of school, and wind up living in a van down by the river. But just because something may be true does not make it a foolproof strategy.

Our redoubtable Professor P realizes that while “suffering” might be a short-term solution, it will not win the zealous commitment of the audience to revision. Thus, P tries a third approach: “You should all work very diligently on revising and editing your arguments because you will earn higher grades if you do.” Ah. Do you see the difference? This tactic has the dual merits of being both true (editing carefully = better grades) and good news; getting better grades is presumably something your audience likes and wants. The teacher has thus employed a fully audience-based reason without selling out the object (carefully edited essays) or alienating the recipients of the message. It is a win-win. Will that reason make the students revise their essays more thoroughly? It is the best argument for doing so, at any rate, and that is all you, as the author, can manage.

To return for a moment to those coal miners, suppose the arguer says, “We have to close down the mines because of the endangered Spotted North American Whirlygig.” Do the miners care about that animal? Have you given them any reason to? You could try that tack, of course, by making claims about the balance and harmony of nature and if we let the Whirlygigs go extinct, the next thing we know it could be us! That is possible, but you should know you are going to have to overcome several significant obstacles, and you are asking the miners to either overlook their own self-interest or to take a very long view of self-interest. Be aware of the strengths and weakness of your reasons as they relate to your audience.

Trying something else, then, might make for a more immediate appeal: “We have to close down the mine because it is polluting the atmosphere and the drinking water for miles around.” If some of the miners agree that air and water are important, those reasons may be sufficiently audience-based. But they may also have very reasonable fears about their economic security that may override their environmental awareness. You could try a more pathos-laden approach, “We have to close down this mine because it is polluting the air your babies breathe and the water your momma drinks,” but that is rather akin to a threat, is it not? And remember that we want to use pathos in conjunction with reason and evidence, not instead of them.

What you will have to do at this point is expand on your chain of reasoning to incorporate their legitimate self-interest. “We have to close this mine down because the pollution is problematic; the coal will eventually run out, and then you’ll be out of a job anyway with no prospects, but this way we can control what happens next; and embracing new job or energy opportunities means a better, safer, and more economically secure world for your families.”

Will that do the trick, like a magic bullet? Almost certainly not – if it were “the answer,” we would be closing coal mines and just telling the miners the above. There are some claims an audience simply does not want to hear and few things you can offer will make them like your claim any better, but you still must try and base your reasoning in what your audience is most likely to value

The Argument Spectrum, or “Who You Can and Cannot Argue With”

In this Handbook, we have referred several times to the idea of a “reasonable person” as a necessary component of argumentation. What does that mean, exactly? In short, you must always remember that for any position imaginable, someone will hold it. No matter how bizarre, how inhumane, or how inexplicable, you can probably find someone (perhaps even a whole Facebook Group of someones) who would defend that position. Does this mean you have to take these people seriously and engage them? Good news: No, no you do not.

Fairness is good, and you should always try to be fair, but being open-minded does not extend to being empty-headed. For the academic writing you will be doing in Composition II, there is the expectation you will take the opposition seriously and summarize their ideas neutrally. That expectation does not mean every kind of opposition is equally applicable, though. Do you remember when we discussed Sophistry earlier and its rejection of objective standards? That rejection is what makes it so very hard to genuinely argue with a Sophist. To a Sophist, all arguments may be valid (or at least useful), but if they are all equally good, then they are also equally bad, if you follow. That is not a problem for a Sophist, but it creates difficulties for other arguers. It is therefore a kind of Sophistry to pretend that all ideas are more-or-less deserving of serious attention. “Why don’t we teach both sides?” sounds like a good formula – that is what makes it so attractive and (apparently) sensible – but think for a moment about the implications of that notion. Should we teach Alchemy alongside Chemistry? Should we teach Phrenology alongside Psychology? Should we teach Astrology alongside Astronomy? Should medical schools go back to teaching the theory of the bodily Humors? It is a kind of Sophistry to say things like “Some people believe the Earth is flat, and some believe it is round” as though that was something like a 50-50 split. You should not exaggerate the standing of fringe ideas, nor should you pretend that a mainstream idea is in fact an outlier.

At the same time, you do not get to decide on a whim that a given position is not reasonable and therefore not worth your argumentative time. It would be nice if there were an agreed-upon set of criteria for what constitutes a reasonable position, but there is not. It is not as though you can say “If 51% of people think Z is true, then it is valid.” Not everything can be measured in that way. How will you decide then? Experience is the best teacher, so be aware of the world around you, seek new sources of information, read widely, read deeply, and ask your teachers many, many questions. You will learn what “reasonable” means in the same way you learned any sort of socially determined sense of scale: by paying attention. If you go on a first date with Person X, and at the pizza buffet Person X has taken eighteen slices of pizza, you will recognize that is not normal. How many slices is normal? You understand there is a range, but eighteen is probably beyond the pale. Do you know that because you learned it in school? Not exactly, no.[7]

It may also be true that no two people will have exactly overlapping senses of what the right range of responses might be, but if your assumptions can be shared broadly, they are more likely to be reasonable.

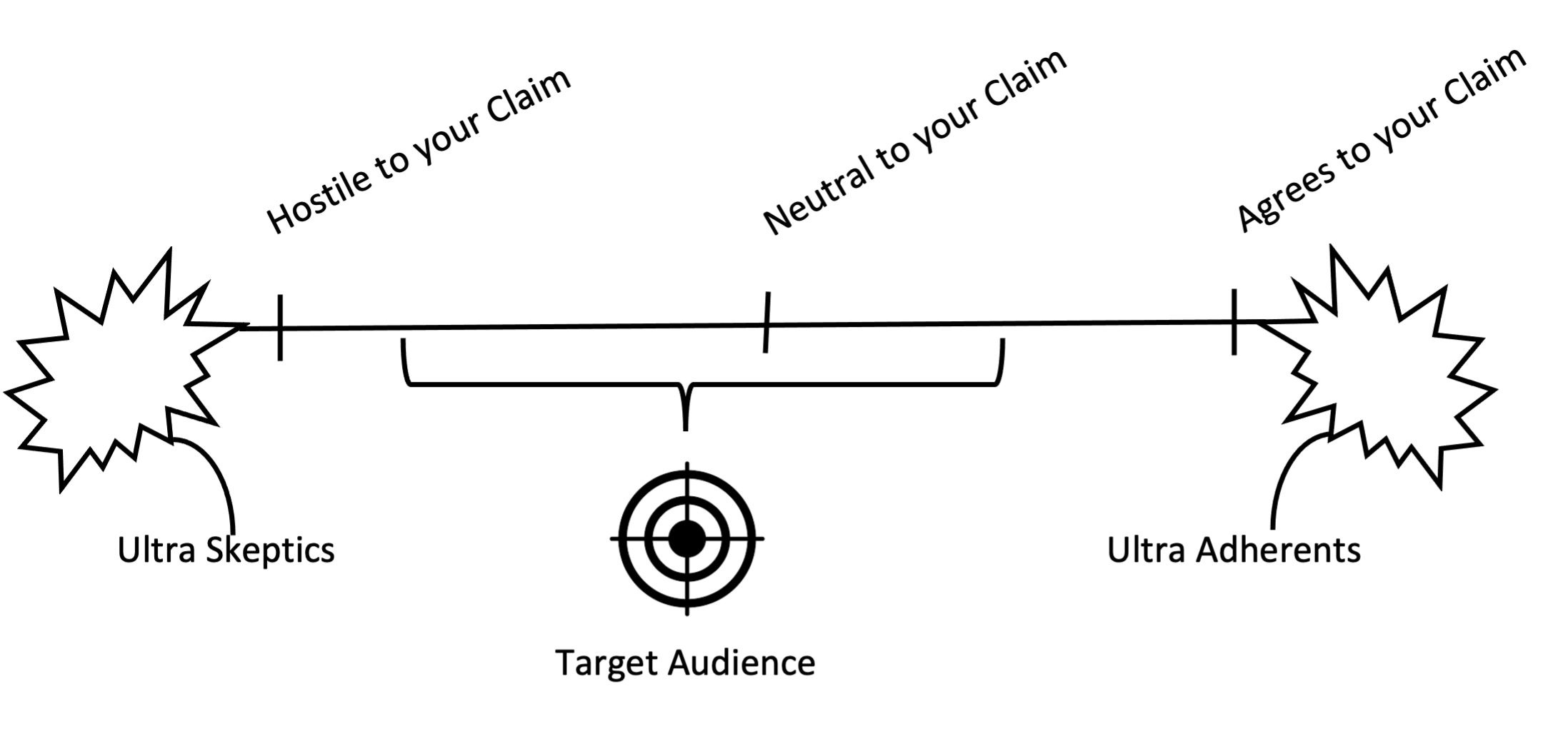

Imagine the Argument Audience spectrum as looking something like this:

Let us begin with those bursts of noise at either end of the spectrum. On the left end, you have the people who are impossible to argue with because they grant no assumptions, share no common ground, and refuse to accept the factual basis of any evidence.  These lost souls are the Ultra Skeptics, and you want to avoid them. These are the people who would be willing to deny the existence of gravity if it suited them. These are the people who will derail the argument by questioning the very nature of a “fact” in ways that would undermine the possible existence of facts. “Sure,” a Skeptic will say, “a dropped pen has always fallen to the floor, but maybe it won’t the next time you drop it.” Wish them well and walk away because you cannot productively argue with this lot.

These lost souls are the Ultra Skeptics, and you want to avoid them. These are the people who would be willing to deny the existence of gravity if it suited them. These are the people who will derail the argument by questioning the very nature of a “fact” in ways that would undermine the possible existence of facts. “Sure,” a Skeptic will say, “a dropped pen has always fallen to the floor, but maybe it won’t the next time you drop it.” Wish them well and walk away because you cannot productively argue with this lot.

Not that the bunch at the other end is any more useful. These are the Ultra Adherents, and they believe what they believe with a tenacity impervious to evidence, logic, or emotional appeal. They believe what they believe precisely because they believe it, and they know it is true because they believe it! You have seen an example of this in the unfortunate mother being interviewed by the local news after her son has been arrested for a string of heinous crimes. Asked about her son’s guilt, she says “Oh, no, not my boy. I  know my son, and he would never do those things.” “What,” the reporter might venture, “about the fingerprints, DNA evidence, video footage, and multiple eyewitness accounts?” “Uh-uh,” says Mother, “that can’t be my son.” No new ideas or interpretations are possible with Adherents, who cling, limpet-like, to what they know to be true. Wish them well and walk away because you cannot productively argue with this lot, either.

know my son, and he would never do those things.” “What,” the reporter might venture, “about the fingerprints, DNA evidence, video footage, and multiple eyewitness accounts?” “Uh-uh,” says Mother, “that can’t be my son.” No new ideas or interpretations are possible with Adherents, who cling, limpet-like, to what they know to be true. Wish them well and walk away because you cannot productively argue with this lot, either.

Like many spectrums, if you travel far enough in one direction you start to come around to the other side, and in this case that would take you to the realm of the Conspiracy Theorists: where they will adhere fervently to something unfounded because they are too skeptical of the actual evidence or they regard the lack of evidence itself as a kind of evidence. For some people, it is more comforting to believe something elaborately constructed on half-understood half-truths. Walk away slowly and return to the spectrum proper.

Since the Skeptics and the Adherents are really beyond the “reasonable” part of the range, we can dispense with them[8] and move on to the kinds of audience environments where real argument is sustainable.

If you glance back up at the Argument Spectrum, then, you will see that the gamut runs from those who are outright hostile to your viewpoint to those who are wholehearted in their agreement with you. Even the extremes of this range are going to be hard to argue with (though not impossible). Instead, to the extent that you are visualizing and making your audience concrete, you want to focus your effort on the highlighted range called the “target audience.” You will notice that the target audience skews to the left, or disagreeing, end of the range and that is so for the very simple reason that those are the people you most need to convince.

As you move further to the right on the scale, as your audience agrees more and more with you, the less argument you actually need to bother with. Remember that argument requires conflicting assertions, so it is not argument if every time you venture some point your audience says, “Yes, absolutely true!” In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates always seemed to have quite cooperative audiences, but we understand the need to make a point, so we will move on. In any event, your work will begin closer to that middle point where the audience is more neutral regarding your claim. Just a word on being neutral: it does not mean “indifferent” or “uncaring,” and there is an important distinction to be made between someone who is “disinterested” – which means “has not taken a side” — and “uninterested” — which means actively put off by the topic or argument. A neutral is someone open to argument from either direction, curious, wanting more information, etc. This is a reader who is prepared to evaluate claims and has an interest in the settling of the question. A neutral may have adopted that position out of a respect for the complexities of the issue and is awaiting further analysis. A neutral is not Switzerland, staying out of the fight; a neutral is waiting to be convinced your cause is just. This is your job.

Moving to the left brings more resistance, more conflict, and thus – to a point – more room for argument. That is why the target audience is not precisely centered, and your fruitful field is primarily going to be an audience who are inclined to think you are wrong. If you write your essays always imagining an audience skeptical of your claims and evidence, you will do well. As with most things, of course, eventually there are diminishing returns and the audience’s skepticism will curdle into outright hostility (to the argument, not you – remember, these are the reasonable people) and not much more can be done. One must take victories where they can be had, so you may consider yourself and your argument well-served if you have moved your audience a little further to the right. As we have discussed, argument is a long game, and you have not lost if, at the end of it, your audience says “Well, I’ll think about it.”

How should you go about accommodating an audience when you already know its disposition to your claim? There are multiple strategies depending on your rhetorical needs and skill. Leaving aside the non-starters on either end, imagine a spectrum like the first one:

| Hostile | Neutral | Agreeing |

| * delayed thesis | * classical argument model | * up-front thesis |

| * Rogerian argument | * balance of ethos, logos, pathos | * more emphasis on emotion |

| * use of humor (?) | * fair rebuttal of opposition strengths | * not much acknowledgement of opposition |

Several of the strategies referenced here will be treated separately. At the moment, we can quickly work through several of the others. When you are addressing an audience which agrees with you, you are essentially acting as a cheerleader or motivational speaker, trying to build the audience’s enthusiasm and commitment to the cause. These sorts of appeals are heavy on the emotions, lighter on the logic, and normally dismissive of the opposition claims. Writers sometimes call them “one-sided arguments,” but as a genuine argument requires two or more sides, that term seems a misnomer. In any event, it is not likely you will be asked to do much of this kind of writing. You want more of a challenge, anyway, right?

The group in the middle will be the primary focus of the rest of this Handbook, so we will keep going and move to the methods for a hostile audience. “Rogerian” argument will be covered in “Other Common Types of Argument,” so that leaves (at least) two other approaches. Of those two, one of them is highly iffy and difficult to pull off successfully, and the other is more time-tested and reliable.

Using humor is a sort of high reward/high risk affair. Since a sense of humor is such a subjective thing, what you find hilarious, your audience might simply read stony-faced and grim. The upside is great, though; you will reach your audience in a way that disarms much of their hostility and makes them more susceptible to your appeals. You might even achieve the pantheon of great humorous or satiric essays and be anthologized for future generations alongside works like Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” or Brady’s “I Want a Wife.” That path is a very narrow way, though, and if you do it wrong, you will crash and burn; not only will your audience fail to appreciate your argument, your misfire may even move them further into the opposition camp. Notable attempts include . . . well, an essay does not often get to be notable if it fails, although it may be worth mentioning that for Swift or Brady, the English occupation of Ireland and social sexism did not exactly go away, so they didn’t “succeed” so much as “succeed in making their points well.” If you do not make your point well, though, on top of not reaching your goals, there is the ignominy of disappearing like so much water into the sand. Use humor sparingly, wisely, and skillfully, if you can.

More dependable is the approach called “the delayed thesis.” As you will see, in a more typical argument, the writer will be very clear about the thesis very early. The thesis will then be supported by much evidence used appropriately. In delayed thesis arguments, as the name suggests, the thesis does not come as early. If you are faced with a room full of people staring at you, with their arms crossed at their chests in body language that unmistakably says, “I do not agree with you,” surely you see that it is not a good start by saying “What you have thought up until now is wrong”? No, that will not do. You are going to have come at this more obliquely, and the delayed thesis is just the right approach. The tactic here is to marshal your evidence first and arrange it in such a way that it makes an implicit argument. The ideal is for a reader of your argument to pause and say, “Huh – we should really be doing Thing X in a different way, then.” Once you have prepared the audience to recognize that a problem exists and there may need to be a novel approach to it, then, with the delayed thesis, it just so happens you have such a solution at hand. “You want a new answer? Why, there’s one right here!” Again, there is some risk in this approach because you need the evidence to “speak for itself” – which evidence rarely does, of course. That is where your careful selection and framing of evidence and reason and emotion come into play.

True, a hostile audience may not come around, even if you are hilarious and even if your evidence speaks volumes. The conversion moment where people jump to their feet after reading something and realize they have been going about it all wrong and it is time to perform a 180° turn in their lives is highly unlikely. It happens – it may even have happened to you on some issue – but a good arguer would be foolish to count on it. Remember that your work may simply be the first planted seed, or the first crack in the dam, or however you want to visualize it. Argument is the long game; bring your audience along by increments if need be.

- If that benefit is also good for us, the writers, so much the better, but if you are writing with the primary purpose of making your own life better, you may want to re-examine your ethical code. ↵

- Or in corners of the dark internet, whichever is worse. ↵

- We assume you are as good as you ought to be. ↵

- Well, perhaps “more so.” ↵

- We will have to assume Timmy and Tommy are not playing baseball and thus wearing gloves, I suppose. ↵

- Is there a “You should not work hard on editing” side of an argument? Perhaps only passively. ↵

- Maybe in Health class? ↵

- But be warned: They’re out there, and you will have to deal with somebody like that eventually. ↵