takenga mai o te reo pakeha

“When you have a dream, you’ve got to grab it and never let go.”

– Carol Burnett

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we, as an English Department, consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

| Anglo | Anglo is a prefix indicating a relation to, or descent from, the Angles, England, English culture, the English people or the English language |

| Saxon | relating to Saxony or the continental Saxons or their language. |

| Old English | the period of time between around 450-1100AD when English was developing vocabulary. |

| Middle English | the period between around 1100-1500AD as English grew and became more popular due to colonisation and reciprocal usage of native languages. |

| Modern English | the period from around 1500 to the present where English continues to change significantly. |

Learning Objectives

- Articulate the origins and influences of the English language and several key events in the history of the language that have affected the development of the language.

- Identify the three main eras of English language: Old English, Middle English, Modern English.

Exercises

Spelling

| abalone | encyclical | rampage | anticipated | hinder |

| augmented | resolve | mishap | coerce | infiltration |

| quirk | optional | relative | prominent | legitimate |

| entire | belittle | pummelled | rebuke | commending |

Vocabulary Builder

Choose the synonym for each of the words in italics. For some you will need to use dictionary definitions for nearly all the words to make sure you get the right one. As you go through them, try to make a note of new words to add to your vocabulary.

- Which word means the same as garbled?

- lucid

- unintelligible

- devoured

- outrageous

- Which word means the same as expose?

- relate

- develop

- reveal

- pretend

- Which word means the same as grotesque?

- extreme

- frenzied

- hideous

- typical

- Which word means the same as erroneous?

- digressive

- confused

- impenetrable

- incorrect

- Which word means the same as coerce?

- force

- permit

- waste

- deny

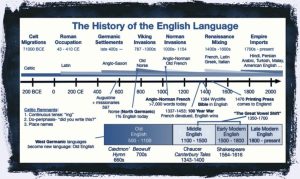

History of the English Language

takenga mai o te reo pakeha

In order to know where we are now, we need to know where we have been.

All words have stories. Humans love to tell stories and to tell those stories to the younger generations as a way of passing on knowledge.

In looking at the language of English, it is really important to look at the history of England. The two are (obviously, due to the name) strongly linked.

All the words that we have in the English language (and there are about 1 million words) originate, or come from, another language. English is often called a ‘magpie’ language because – like the birds – they saw what others had, and they stole it from them. Magpies are known to steal shiny things and put them in their nest, and the English are known to steal words and include them in their language when they didn’t have a similar word – or even when they did.

The Celts:

The first in a long line of people in charge of England were the Celts. We still have some of their history on show with Stone Henge (the collection of extremely large boulders arranged to capture the light of the equinox. What is left of Stone Henge can be seen in Wiltshire in the UK. If you are in the UK you should definitely head along to see it.

The first in a long line of people in charge of England were the Celts. We still have some of their history on show with Stone Henge (the collection of extremely large boulders arranged to capture the light of the equinox. What is left of Stone Henge can be seen in Wiltshire in the UK. If you are in the UK you should definitely head along to see it.

The Celts spoke a language called Gaelic (originally called the Gaulish language). We still use some words that originate from this language including bran; valet; piece; and truant.

The Romans: 55BC

The first Roman to step foot on England was the great soldier of the Roman army – Julius Caesar. The Romans came up through the Thames and established what is now London (but called Londinium at the time). They also loved their baths – you can still see these in the South West of England in an area called, well, Bath. The ‘Roman Baths’ have remained relatively intact.

The first Roman to step foot on England was the great soldier of the Roman army – Julius Caesar. The Romans came up through the Thames and established what is now London (but called Londinium at the time). They also loved their baths – you can still see these in the South West of England in an area called, well, Bath. The ‘Roman Baths’ have remained relatively intact.

The Romans spoke Latin and so they added to the Celtic language with their own influences. Words like ‘first’ and ‘foliage’ have stuck around, but not many others have been retained from this period.

The Anglo-Saxons: 450AD

The foundations of the English language began with the arrival of the Angles and the Saxons (and the Jutes – but they don’t get recognised very much) to the English shores.

The foundations of the English language began with the arrival of the Angles and the Saxons (and the Jutes – but they don’t get recognised very much) to the English shores.

Latin was overtaken by a new language that was simple to use and gave the people of England names for things like loaf and house. These tribes of warriors were from the Germanic region (Germany wasn’t a country at this stage) and they have been united under the branding of the Anglo-Saxons. Four of our days of the week are named after their Gods.

Tuesday : Tiw / Tyr (God of Single combat, victory and heroic glory);

Wednesday: Woden (God of healing, death and royalty);

Thursday: Thor (God of thunder, lightning and storms);

Friday: Frigg (associated with Roman Goddess Venus).

Christian Missionaries: 560 AD

Christian Missionaries: 560 AD

Christian missionaries from around Europe began to move into England bringing with them Catholicism and also new words, largely derived from a modern form of Latin including Martyr, Bishop, Font. Christianity was a success in Britain so the Anglo-Saxon language began to amalgamate with the more modern form of Latin.

The Vikings arrive: 800AD

Largely due to overpopulation in their own country, Vikings from the Scandinavian region of Norway, Sweden and Denmark begin to invade Britain and added drag, ransack, thrust and die to the vocabulary. They needed to find areas of fertile ground in order to exist. So bad was the famine in the land that the land owners had to ‘draw lots’ to decide who would need to leave the country and live abroad in an effort to reduce the strain of overpopulation. England had vast amounts of uninhabited land, and fertile soil for growing food. However, they were portrayed as brutal beings that were blood thirsty due to some large scale fights that broke out when land was taken by the invaders. They added give and take and around 2000 words to the English language. Words from the Vikings are called Old Norse words. Any place names in England that end in ‘-by’ such as Thornby, Kirby Cross, and Crosby come from this era (by is the Old Norse word for town).

Largely due to overpopulation in their own country, Vikings from the Scandinavian region of Norway, Sweden and Denmark begin to invade Britain and added drag, ransack, thrust and die to the vocabulary. They needed to find areas of fertile ground in order to exist. So bad was the famine in the land that the land owners had to ‘draw lots’ to decide who would need to leave the country and live abroad in an effort to reduce the strain of overpopulation. England had vast amounts of uninhabited land, and fertile soil for growing food. However, they were portrayed as brutal beings that were blood thirsty due to some large scale fights that broke out when land was taken by the invaders. They added give and take and around 2000 words to the English language. Words from the Vikings are called Old Norse words. Any place names in England that end in ‘-by’ such as Thornby, Kirby Cross, and Crosby come from this era (by is the Old Norse word for town).

Around 900AD England gets its first King, Athelstan thus beginning a long line of Monarchical power in the country. Up to this point Kings have had dominion over certain regions within the country, but Athelstan is the first King of all England.

The Norman Invasion: 1066AD

William the Conqueror invades England and brings new concepts from Europe including the French Language and the Doomsday book (a survey to determine what taxes were owed). Council (from Cuncile) was added in 1125; Parliament (from Parlement) in 1290; Clerk (from Clerc) in 1129; Sovereign (from Souverain) in 1290.

William the Conqueror invades England and brings new concepts from Europe including the French Language and the Doomsday book (a survey to determine what taxes were owed). Council (from Cuncile) was added in 1125; Parliament (from Parlement) in 1290; Clerk (from Clerc) in 1129; Sovereign (from Souverain) in 1290.

- French became the language of justice (Judge – 1290; Jury – 1400; Evidence – 1300).

- Latin was used in Church retaining the Roman Catholic heritage.

- English (now made up of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Modern Latin) was spoken by the common man.

Words like cow, sheep and swine came from English peasant farmers, while beef, mutton and pork came from the French. The English absorbed or reformed around 10,000 words in this period from the Normans. (from Normandy – an area in northern France)

The 100 Year War: 1337 – 1453AD

After a lot of unrest following the Norman invasion and subsequent Kingship. King Edward III led England into a war with France to remove the perceived French aggressors. Edward III transformed England into a formidable military power and found the strength in the armies and navy to attack France. The English were victorious and English as a language took over as the language of power and therefore the language of the British isles.

After a lot of unrest following the Norman invasion and subsequent Kingship. King Edward III led England into a war with France to remove the perceived French aggressors. Edward III transformed England into a formidable military power and found the strength in the armies and navy to attack France. The English were victorious and English as a language took over as the language of power and therefore the language of the British isles.

William Shakespeare: 1564 – 1616

The only individual to have an impact on the English language is William Shakespeare, adding about 2000 words and phrases to the English Language.

The only individual to have an impact on the English language is William Shakespeare, adding about 2000 words and phrases to the English Language.

Eyeball, puppy dog, anchovy, dauntless, besmirch, lacklustre, alligator, hob-nob, ‘flesh and blood’, ‘out of house and home’, ‘good riddance’, ‘green-eyed monster, ‘breaking the ice’, ‘as dead as a doornail’, ‘get your money’s worth’, ‘short shrift’

Shakespeare showed the European world that English did have the vocabulary to express love and other desires with limitless power. It was beginning to have an impact internationally.

The translation of the King James Bible: 1611AD

King James I of England was the ruler after Queen Elizabeth I. Both were the reigning monarchs during Shakespeare’s life. James ordered a new translation of the bible into Old English. Again this added a number of words and phrases to the English language.

King James I of England was the ruler after Queen Elizabeth I. Both were the reigning monarchs during Shakespeare’s life. James ordered a new translation of the bible into Old English. Again this added a number of words and phrases to the English language.

‘the powers that be’, ‘turned the world upside down’, ‘labour of love’, ‘wisdom of Soloman’, ‘go the extra mile’, ‘all things to all men’, ‘hearts desire’, ‘fight the good fight’, ‘from strength to strength’, ‘to the root of the matter’, ‘salt of the earth’, ‘ writing was on the wall’, ‘to the ends of the earth’, ‘fly in the ointment’

The King James bible shaped the way English is spoken today with its emphasis on storytelling, figurative language and idiom. There are few individual books that have a greater impact on the English language.

Before the 17th Century Scientists in Britain were not recognised, however, a number of Physicists became popular in the latter half of the 1600s. Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton to name a few. The Royal Society of Physicists was formed in 1660. At first they worked in Latin according to the principle of Latin and Rome being the centre of technological development. They discovered that the impact they could have on society was greater if they spoke the language of the common man.

Science; however, was discovering things faster than they could name them. Acid (1626); gravity (1641), electricity (1646), pendulum (1660). These words were based on Latin origins.

Science; however, was discovering things faster than they could name them. Acid (1626); gravity (1641), electricity (1646), pendulum (1660). These words were based on Latin origins.

Scientists also began to name body parts. Cardiac in 1601, tonsil in 1601, and sternum in 1667. These were the results of many dissections which had become common place in England.

The New Era of English: 1583 – 1914AD

English was now the language of Science, the bible and Shakespeare Britain began to become adventurous and venture to new lands. From the Caribbean England claimed land and loyalty, and in return took Barbeque (1650), Canoe (1550) and Cannibal (1550). In India they took Yoga (1820), Cummerbund (1610), Crimson (1500), and Bungalow (1670). In Africa there were words like ‘Voodoo’ and ‘Zombie’. From Australia English took the words ‘nugget’, ‘boomerang’ and ‘walkabout’.

Modern English: 1914 – Now

Between defeating Napoleon and the first world war England claimed around 10 million square miles of land and 400million people. This allowed for dialects or strains of English to form all around the globe. The separation from the Motherland of England meant that languages evolved on their own.

With English developing in numerous directions a group of men called lexicographers began to chart and research the spellings of the various words in the English Language. Dr Johnson wrote the first dictionary (1746-1755) which upon publication, became obsolete. It contained over 42,000 entries and was 18 inches in length. In 1857 another book was created that would be known as the Oxford English Dictionary, which continues to be revised to this day. It took 70 years to be finished and was published in 1928.

From the moment the British landed in America they needed names for the plants and animals that were so foreign. ‘Racoon’, ‘squash’ and ‘moose’ were added to the registry. In America, other cultures began to arrive. The Dutch brought ‘coleslaw’ (1794), ‘cookie’ (1703). Germans added ‘pretzels’ (1856) and ‘delicatessen’ (1889) and the Italians brought ‘pizza’ (1935), ‘pasta’ (1874) and ‘mafia’ (1875).

American brought capitalism to the forefront with ‘breakeven’ and ‘bottom line’ (1967) adding ‘blue chip’ and ‘white collar’ in the early 1920s. The ‘commuter’ (1865) needed ‘freeways’ (1930), and ‘subways’ (1893) so that ‘mergers’ and ‘downsizing’ could be achieved. American English became popular in England as the two nations competed for dominance in the 1900s. ‘cool’ and ‘groovy’ were adopted by Britain. Old English words – fall, faucets, diapers and candy were retained in America, while autumn, tap, nappy and sweets were used in Britain.

American brought capitalism to the forefront with ‘breakeven’ and ‘bottom line’ (1967) adding ‘blue chip’ and ‘white collar’ in the early 1920s. The ‘commuter’ (1865) needed ‘freeways’ (1930), and ‘subways’ (1893) so that ‘mergers’ and ‘downsizing’ could be achieved. American English became popular in England as the two nations competed for dominance in the 1900s. ‘cool’ and ‘groovy’ were adopted by Britain. Old English words – fall, faucets, diapers and candy were retained in America, while autumn, tap, nappy and sweets were used in Britain.

Internet English

1972 the first email is sent. In 1991 the internet became popular. Download was in 1980. Firewall in 1990. Conversations and typing became normal. The shortening of phrases IMHO and BTW. Some phrases moved into spoken English. FYI and LOL.

Global English

In the 1500 years since Romans left England the language has been able to adapt, improve and steal from other nations. First it was the language of the high seas (which spread to travel in general) and then through the internet (designed by a Brit) taking words from over 350 languages. All this using an alphabet that has no correlation to how it sounds and unusual spellings that are more code than anything else. Around 1.5 billion speak English and about a quarter of which speak it as a native tongue. A quarter have it as a second language and the rest have basic comprehension.

An extract from Katipo Joe by Brian Faulkner

Chapter 1: The Stranger

Thursday, 13th October 1938

THE STRANGER ARRIVED well after midnight. The boy was awake instantly, alerted by the tiniest sound of the scullery door being gently closed. A glance at his broken cuckoo clock told him the time. His parents must have been expecting the stranger because they had waited up, and Joe could hear the soft murmurings of their voices. The stranger had come in by the back door, which was odd. Visitors usually entered through the front door. But then again, visitors did not usually call after midnight, so this was odd in many respects. The back door led out from the scullery into the dark service alley that ran behind the houses, which was a good way to come if you did not want to be noticed. Something out of the ordinary was happening this night.

Joe lay still for a moment, breathing in an awareness of the immediate universe that surrounded him. That’s what the hero always did, like Lieutenant Urquhart in Detective Yarns, or Secret Agent Troy in Hutchinson’s Adventure Story Magazine, the most recent issue of which he had received for his twelfth birthday. He used all his senses, like the hero always did. Feeling – tasting – smelling – listening – looking.

The bed he lay in was warm and soft, he felt. The big goose-down quilt, a warm cloud enveloping him. The pillow was thin and a little hard, but he preferred it like that. Big soft pillows always seemed to be trying to smother him.

He tasted a slight aftertaste of Doromad, the toothpaste that his mother made him use twice a day. She liked it because it was slightly radioactive and killed germs. Joe didn’t like it. He was afraid it would make his teeth glow in the dark.

He smelled a slight tang of pipe smoke in the air. His father only smoked when he was upset and almost never this late at night.

From her small wicker basket in the corner, he heard a soft snuffle from Blondie, his new Alsatian puppy. She was a gift from the Ambassador himself for Joe’s birthday and was the centre of Joe’s life. He had wanted to call her Betty, after Betty Grable, the beautiful American actress, but his mother hadn’t approved of ‘that temptress,’ so he had compromised and called her Blondie instead.

The drapes were open, he saw, letting in the clear night sky. The lower three stars of the Orion constellation were visible just below the top of the window. The sword of Orion. The telescope (actually a big old brass ship’s telescope that his father had borrowed from the Embassy) stood proudly on its wooden tripod by the window, staring endlessly out the window at the sky and stars beyond. Keeping watch over the night skies … for what, Joe didn’t know.

His football sat on the dresser at the end of the bed. The brown leather showed shiny edges from years of battering, but commanded pride of place in the room. That ball had helped his team win the school age-group championship. It was a great ball. On the far wall was pinned a poster of Fritz Szepan, captain of the German national side through the last two World Cups.

A sliver of light from the slightly open bedroom door lay across the face of the broken cuckoo clock on the wall. The small hand was nearly at the one, but the big hand was camouflaged by the gloom. The cuckoo, half in and half out of its little home, looked back at him, its eyes twinkling with amusement. The cuckoo never went home any more, nor did it fully emerge to announce the hours in its mechanical cuckoo voice. Not since Joe had decided to take the clock apart to find out how it had worked.

Joe lay still for a moment longer, his eyes on the bird, but his mind occupied listening to all the clues that the quiet of the night brought him. The low, but urgent, murmur of voices. The soft footsteps in the passageway downstairs. The quiet clunk of the hallway door closing, and a small click as it was latched.

Finally, happy that he was fully aware of the world that surrounded him, the complete master of this little piece of the universe, he rolled out from under the thick quilt and stood up … putting his right foot smack in the centre of his chamber pot. He was relieved to find it was empty.

He padded silently in his thick bed socks to the door of his room. On a hook on the back of the door was his dressing gown, which he quickly donned against the cold night air.

He drew the door open with a sharp jerk that he knew would prevent it from creaking, then paused to assemble his team. This was not a mission he wanted to undertake by himself. Four of his favourite tin soldiers immediately volunteered and, secreting them in the pocket of his gown, he moved stealthily into the hall.

Down the staircase, missing the third step because it creaked … so did the seventh … and the last. Around the corner to the hallway. Listening at the door for any noise in the passageway beyond. A quick glance through the crack between the door and the jamb to confirm. Then carefully sliding the door latch upwards with a slip of thick cardboard that he kept in the pocket of his dressing gown for just that purpose. Pushing the door open just wide enough to slip through and easing the latch silently back into place. Leaving the door open a tiny fraction, so that it looked closed but would allow him a quick exit. You must always have an escape route. That’s what Agent Troy said.

The voices from the scullery were louder now, but still muffled. Joe slid his bed-socked feet across the polished floorboards into the kitchen, which adjoined the scullery. The room was warm. The coal stove had been kept stoked up; no doubt in anticipation of the stranger’s arrival. It was dark and he moved carefully so as not to trip over a pot or other utensil that the maid might have left on the floor.

From the next door room he heard his mother’s voice. Reassuring, calming. Then his father’s more urgent, querying tone. “Why do you think Michaelson didn’t show?” Joe’s mother replied, quietly, “Perhaps he was delayed, or it just wasn’t safe to travel.”

“Perhaps,” his father agreed, “but these days …” Joe sat, stretching out his legs on the hard wooden floor. He slipped a hand into the pocket of his dressing gown and pulled out the four toy soldiers, placing them on the floor in front of him. Three were British grenadiers, resplendent in their bright red uniforms. The fourth was a French musketeer. The French one was a little worse for wear, the blue paint having worn off in a number of places, exposing the tin beneath. The French never did very well in Joe’s battles.

“If the Gestapo have him …” This was a voice Joe didn’t recognise. The stranger. There was a tone to it that was unsettling. Joe identified it as desperation, or terror, or both.

The night was getting interesting. “He wouldn’t talk,” his mother said quietly. “And in any case, he doesn’t know anything about you but your code- name.”

Joe’s musketeer became Michaelson, suddenly trapped in a dark, lonely alley by the three grenadiers, now evil agents of the much-feared Gestapo.

Bam! Michaelson kicked away the gun of the first agent and head-butted the next one in the stomach. The third took a shot at him with his Luger, but Michaelson was too fast and dived to the ground, picking up the first agent’s gun and killing the third Gestapo man with a single shot, before escaping down the alleyway that was actually Joe’s legs.

He dropped one of the Gestapo agents and there was a light clunk as it hit the hard wooden floor of the kitchen.

“What was that?” the stranger asked nervously from the other room.

Joe held absolutely still. “Nothing,” his mother said. “Nothing at all. No, no, I don’t think that was anything to worry about. This house often makes odd noises like that …”

She was talking too much, Joe realised. And his father was silent. She was obviously covering, while his father moved around to deal with the threat. At least that’s what Agent Troy would do.

There it was. The faintest click from the scullery door to the hall. His mother was still going on about the old house and the strange creaks and groans it made.

Joe knew he was going to have to move, and move now. But silently. And to where? He urgently scanned the kitchen. There was a small pile of towels in the laundry basket waiting to go to the boiler the next day. It would have to do. He slid across the floor to the basket, climbed over the edge and curled up inside, scooping the towels up and spreading them on top of himself. They were damp and cold and he gave an involuntary shiver as they touched his face, before commanding his body to absolute stillness. He shut his mouth tightly, in case his teeth really did glow in the dark.

There was a bang, and a glare all around him as the light in the kitchen flicked on. Through a tiny crack in the weave of the basket he saw his father enter the room, poised, alert, dangerous. In his hand he held a dark metal object and it took Joe several moments to realise what it was. He didn’t even know his father owned a pistol!

He knew he was not completely hidden but hoped that the wool of his dressing gown would look like another towel to his father’s searching eyes. There would be severe punishment if he got caught. He knew that for sure.

A piece of coal coughed and shifted in the coal range and, after a moment, the lights snapped off again.

Joe remained motionless until he heard the scullery door close and his father’s voice in the other room. “Must have been the coal range. Nobody there.” Joe eased himself out of the basket and slid back to his position by the wall.

“You have the documents?” his mother was asking. “Yes. They were in the dead-letter box, as planned,” the stranger said.

“No chance of a trap?” “No. I was very careful.” There was a long silence, broken only by the rustle of paper. Joe staged a few more battles between tattered blue Michaelson and the bright red Gestapo agents to fill in the time.

“Okay,” his father said at last. “We’ll microfilm these and get them to London.”

“I hope to God we’re not too late.” That was his mother speaking.

“Do I go back?” the stranger wanted to know. “No, we can’t risk it. If Michaelson has been taken …” His father trailed off.

“Here’s the address of the safe house.” His mother’s voice, and the scratch of a fountain pen. “They’ll ask you for a password, it’s ‘Violet’ – don’t forget it.”

His father said, “Good luck, Dusko.” Joe sensed the meeting was over. Quickly and quietly he re-latched the hallway door and tiptoed back upstairs, pushing his bedroom door to the same angle it had been before.

He was in bed by the time he heard the back scullery door open and the man called Dusko stumble out into the cold and dark of the night.

Joe lay facing away from the door, in case his parents should check on him, and stared out of the window. If he moved his head forward just a little, to get a better angle, he could see the rest of the constellation. Orion, the hunter, was in the night sky. And Joe’s father owned a gun.

Taken from “https://www.thesapling.co.nz/single-post/2020/05/11/the-sampling-katipo-joe-blitzkreig”

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.