What’s cognitive development like during middle childhood?

Children in middle childhood are beginning a new experience—that of formal education. In the United States, formal education begins at a time when children are beginning to think in new and more sophisticated ways. According to Piaget, the child is entering a new stage of cognitive development where they are improving their logical skills. During middle childhood, children also make improvements in short term and long term memory.

Learning Objectives

- Describe key characteristics of Piaget’s concrete operational intelligence

- Explain the information processing theory of memory

- Describe language development in middle childhood

- Describe Kohlberg’s theory on preconventional, conventional, and postconventional moral development

- Differentiate between achievement and aptitude tests

- Compare Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences and Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence

- Apply the ecological systems model to explore children’s experiences in schools

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

| Table 1. Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development | |||

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions | Object permanence Stranger anxiety |

| 2–7 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things but lack logical reasoning | Pretend play Egocentrism Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and logical analogies; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation Mathematical transformations |

| 11– | Formal operational | Utilize abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking | Abstract logic Moral reasoning |

Concrete Operational Thought

According to Piaget, children in early childhood are in the preoperational stage of development in which they learn to think symbolically about the world. From ages 7 to 11, the school-aged child continues to develop in what Piaget referred to as the concrete operational stage of cognitive development. This involves mastering the use of logic in concrete ways. The child can use logic to solve problems tied to their own direct experience but has trouble solving hypothetical problems or considering more abstract problems. The child uses inductive reasoning, which means thinking that the world reflects one’s own personal experience. For example, a child has one friend who is rude, another friend who is also rude, and the same is true for a third friend. Using inductive reasoning, the child may conclude that friends are rude. This is also called “bottom-up reasoning” as they reason from their specific experiences up to general conclusions. (We will see that this way of thinking tends to change during adolescence as children begin to use deductive reasoning effectively.)

The word concrete refers to that which is tangible; that which can be seen or touched or experienced directly. The concrete operational child is able to make use of logical principles in solving problems involving the physical world. For example, the child can understand the principles of cause and effect, size, and distance.

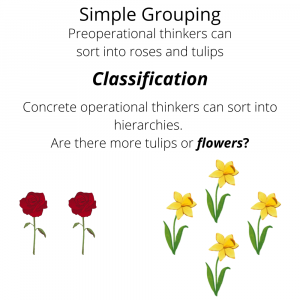

As children’s experiences and vocabularies grow, they build schema and are able to classify objects in many different ways. Classification can include new ways of arranging information, categorizing information, or creating classes of information. Many psychological theorists, including Piaget, believe that classification involves a hierarchical structure, such that information is organized from very broad categories to very specific items. Children are able to group items into a logical order or series, called seriation. For example, in middle childhood, kids can arrange their toys in order from smallest to largest.

One feature of concrete operational thought is the understanding that objects have an identity or qualities that do not change even if the object is altered in some way. For instance, the mass of an object does not change by rearranging it. A piece of chalk is still chalk even when the piece is broken in two. Piaget tested this with the conservation tasks covered in the last chapter. In concrete operations, children master conservation.

During middle childhood, children also understand the concept of reversibility, or that some things that have been changed can be returned to their original state. Water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again. But eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. Many of these cognitive skills are incorporated into the school’s curriculum through mathematical problems and in worksheets about which situations are reversible or irreversible. (If you have access to children’s school papers, look for examples of these.)

Remember the example from the earlier module of children thinking that a tall beaker filled with 8 ounces of water was “more” than a short, wide bowl filled with 8 ounces of water? Concrete operational children can understand the concept of reciprocity which means that changing one quality (in this example, height or water level) can be compensated for by changes in another quality (width). So there is the same amount of water in each container although one is taller and narrower and the other is shorter and wider.

These new cognitive skills increase the child’s understanding of the physical world. Operational or logical thought about the abstract world comes later in formal operations.

Information Processing Theory

Information processing theory is a classic theory of memory that compares the way in which the mind works to computer storing, processing, and retrieving information. According to the theory, there are three levels of memory:

- Sensory memory: Information first enters our sensory memory (sometimes called sensory register). Stop reading and look around the room very quickly. (Yes, really. Do it!) Okay. What do you remember? Chances are, not much, even though EVERYTHING you saw and heard entered into your sensory memory. And although you might have heard yourself sigh, caught a glimpse of your dog walking across the room, and smelled the soup on the stove, you may not have registered those sensations. Sensations are continuously coming into our brains, and yet most of these sensations are never really perceived or stored in our minds. They are lost after a few seconds because they were immediately filtered out as irrelevant. If the information is not perceived or stored, it is discarded quickly.

- Working memory (short-term memory): If information is meaningful (either because it reminds us of something else or because we must remember it for something like a history test we will be taking in 5 minutes), it moves from sensory memory into our working memory. Things we pay attention to enter our working memory. Working memory consists of information that we are immediately and consciously aware of. All of the things on your mind at this moment are part of your working memory.

There is a limited amount of information that can be kept in the working memory at any given time. For most people, this is somewhere 5 to 9 (7 + or – 2) pieces or chunks of information. If you are given too much information at a time, you may lose some of it. (Have you ever been writing down notes in a class and the instructor speaks too quickly for you to get it all in your notes? You are trying to get it down and out of your working memory to make room for new information and if you cannot “dump” that information onto your paper and out of your mind quickly enough, you lose what has been said.) We can hold info in working memory for about 30 seconds; repeating info in your mind (rehearsal) can help keep it in your working memory, but getting information into long term memory relies on more than simple rehearsal. Information in our working memory must be stored in an effective way to be accessible to us for later use. It is stored in our long-term memory or knowledge base. - Long-term memory (knowledge base): This level of memory has an unlimited capacity and stores information for days, months, or years. It consists of things that we know of or can remember if asked. This is where you want the information to ultimately be stored. The important thing to remember about storage is that it must be done in a meaningful or effective way. In other words, if you simply try to repeat something several times to remember it, you may only be able to remember the sound of the word rather than the meaning of the concept. So if you are asked to explain the meaning of the word or to apply a concept in some way, you will be lost. Studying involves organizing information in a meaningful way for later retrieval. Passively reading a text is usually inadequate and should be thought of as the first step in learning material. Writing keywords, thinking of examples to illustrate their meaning, and considering ways that concepts are related are all techniques for organizing information for effective storage and later retrieval.

During middle childhood, children are able to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to and store information. School-aged children are better able to use selective attention, and attend to particular stimuli while tuning out distractions. As children enter school and learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. New experiences are similar to old ones or remind the child of something else about which they know. This helps them file away new experiences more easily and build a knowledge base.

Children in middle childhood also have a better understanding of how well they are performing on a task and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt studying strategies to meet those needs. While preschoolers may spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, school-aged children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. They develop metacognition or the ability to understand the best way to figure out a problem. Metacognition involves an extra layer: thinking about how they think. They gain more tools and strategies (such as “i before e except after c” so they know that “receive” is correct but “recieve” is not.)

Language Development

Vocabulary

One of the reasons that children can classify objects in so many ways is that they have acquired a vocabulary to do so. By 5th grade, a child’s vocabulary has grown to 40,000 words. It grows at the rate of 20 words per day, a rate that exceeds that of preschoolers. This language explosion, however, differs from that of preschoolers because it is facilitated by being able to quickly associate new words with those already known (fast-mapping) and because it is accompanied by a more sophisticated understanding of the meanings of a word.

A child in middle childhood is also able to think of objects in less literal ways. For example, if asked for the first word that comes to mind when one hears the word “pizza”, the preschooler is likely to say “eat” or some word that describes what is done with a pizza. However, the school-aged child is more likely to place pizza in the appropriate category and say “food” or “carbohydrate”.

This sophistication of vocabulary is also evidenced in the fact that school-aged children are able to tell jokes and delight in doing so. They may use jokes that involve plays on words such as “knock-knock” jokes or jokes with punch lines. Preschoolers do not understand plays on words and rely on telling “jokes” that are literal or slapstick such as “A man fell down in the mud! Isn’t that funny?” Children’s understanding of social cues improves and they are better able to tailor their communication to their audience, which is called pragmatics. Kids understand that they can tell a joke to their friends that would be inappropriate to tell to their grandma.

Grammar and Flexibility

School-aged children are also able to learn new rules of grammar with more flexibility. While preschoolers are likely to be reluctant to give up saying “I goed there”, school-aged children will learn this rather quickly along with other rules of grammar. They become more proficient in the rules of language but are often tripped up by more abstract uses of language, like sarcasm

While the preschool years might be a good time to learn a second language (being able to understand and speak the language), the school years may be the best time to be taught a second language (the rules of grammar).

Moral Development

Lawrence Kohlberg (1963) built on the work of Piaget and was interested in finding out how our moral reasoning changes as we get older. He wanted to find out how people decide what is right and what is wrong. In order to explore this area, he read a story containing a moral dilemma to boys of different age groups (also known as the Heinz dilemma). In the story, a man is trying to obtain an expensive drug that his wife needs in order to treat her cancer. The man has no money and no one will loan him the money he requires. He begs the pharmacist to reduce the price, but the pharmacist refuses. So, the man decides to break into the pharmacy to steal the drug. Then Kohlberg asked the children to decide whether the man was right or wrong in his choice. Kohlberg was not interested in whether they said the man was right or wrong, he was interested in finding out how they arrived at such a decision. He wanted to know what they thought made something right or wrong.

Pre-conventional Moral Development

The youngest subjects seemed to answer based on what would happen to the man as a result of the act. For example, they might say the man should not break into the pharmacy because the pharmacist might find him and beat him, or they might say that the man should break in and steal the drug and his wife will give him a big kiss. Right or wrong, both decisions were based on what would physically happen to the man as a result of the act. This is a self-centered approach to moral decision-making. He called this most superficial understanding of right and wrong pre-conventional moral development.

Pre-conventional development covers stages one and two in Kohlberg’s theory. In stage one, the focus is on the direct consequences of their actions. Their main concern is avoiding punishment and being obedient. In stage two, the focus is more “what’s in it for me”? A stage two mentality is self-interest driven.

Conventional Moral Development

Middle childhood boys seemed to base their answers on what other people would think of the man as a result of his act. For instance, they might say he should break into the store, and then everyone would think he was a good husband. Or, he shouldn’t because it is against the law. In either case, right and wrong are determined by what other people think. Because what other people think is usually a function of socially accepted morality, this view is often thought of as applying society’s standards. A good decision is one that gains the approval of others or one that complies with the law. This is conventional moral development.

The conventional moral development covers stages three and four. In stage three, the focus is on what society deems okay or good in order to gain approval from others. In stage four, the focus is on maintaining social order. The person has an understanding that laws and social conventions are created to maintain a properly functioning society.

Post-conventional Moral Development

Older children were the only ones to appreciate the fact that the Heinz dilemma has different levels of right and wrong. Right and wrong are based on social contracts established for the good of everyone or on universal principles of right and wrong that transcend the self and social convention. For example, the man should break into the store because, even if it is against the law, the wife needs the drug and her life is more important than the consequences the man might face for breaking the law. Or, the man should not violate the principle of the right of property because this rule is essential for social order. In either case, the person’s judgment goes beyond what happens to the self. It is based on a concern for others, for society as a whole, or for an ethical standard rather than a legal standard. This level is called post-conventional moral development because it goes beyond convention or what other people think to a higher, universal ethical principle of conduct that may or may not be reflected in the law. Notice that such thinking (the kind supreme justices do all day in deliberating whether a law is moral or ethical, etc.) requires being able to think abstractly. Often this is not accomplished until a person reaches adolescence or adulthood.

Post conventional moral development covers stages five and six. In stage five, the person realizes that not everything is black and white. The person realizes that there are many different ways of thinking about what is good and what is right. Further, just because there is a law does not mean that the law is necessarily good for everyone. In stage five, then, the idea is to do the most good for the most people. Kohlberg’s sixth stage is interesting in that it does not seem that people make it to this stage and stay. Indeed, many researchers have failed to identify people who operate within a stage six mentality at all, while others have identified a very few people who operate within stage six on occasion. Why might this be the case? Stage six is a way of thinking about the question of morality in a way that is not personal. Instead, a person tries to empathize with other people and to see the world from the other person’s perspective before making a decision. While this sounds easy, very few people are capable of doing this well, and even fewer are capable of doing it consistently. Further, the idea of universal justice is involved in stage six. Indeed, a person in stage six is ready to disobey unjust laws. The focus is on doing the right thing, regardless of the personal consequences.

Watch It: The Heinz Dilemma

The Heinz dilemma is a frequently used example used to help us understand Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. It is described in the following video:

From a theoretical point of view, it is not important what the participant thinks that Heinz should do. Kohlberg’s theory holds that the justification the participant offers is what is significant, the form of their response. Below are some of many examples of possible arguments that belong to the six stages:

- Stage one (obedience): Heinz should not steal the medicine because he will consequently be put in prison which will mean he is a bad person. OR Heinz should steal the medicine because it is only worth $200 and not how much the druggist wanted for it; Heinz had even offered to pay for it and was not stealing anything else.

- Stage two (self-interest): Heinz should steal the medicine because he will be much happier if he saves his wife, even if he will have to serve a prison sentence. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine because prison is an awful place, and he would more likely languish in a jail cell than over his wife’s death.

- Stage three (conformity): Heinz should steal the medicine because his wife expects it; he wants to be a good husband. OR Heinz should not steal the drug because stealing is bad and he is not a criminal; he has tried to do everything he can without breaking the law, you cannot blame him.

- Stage four (law-and-order): Heinz should not steal the medicine because the law prohibits stealing, making it illegal. OR Heinz should steal the drug for his wife but also take the prescribed punishment for the crime as well as paying the druggist what he is owed. Criminals cannot just run around without regard for the law; actions have consequences.

- Stage five (social contract orientation): Heinz should steal the medicine because everyone has a right to choose life, regardless of the law. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine because the scientist has a right to fair compensation. Even if his wife is sick, it does not make his actions right.

- Stage six (universal human ethics): Heinz should steal the medicine, because saving a human life is a more fundamental value than the property rights of another person. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine, because others may need the medicine just as badly, and their lives are equally significant.

Modern Views of Moral Development

Kohlberg continued to explore his theory after the initial theory was researched. He theorized that there could be other stages and that there could be transitions into each stage. One thing that Kohlberg never fully addressed was his use of nearly all-male samples. Men and women tend to have very different styles of moral decision making; men tend to be very justice-oriented while women tend to be more compassion oriented. In terms of Kohlberg’s stages, women tend to be in lower stages than men because of their compassion orientation.

Carol Gilligan was one of Kohlberg’s research assistants. She believed that Kohlberg’s theory was inherently biased against women. Gilligan suggests that the biggest reason that there is a gender bias in Kohlberg’s theory is because males tend to focus on logic and rules while women focus on caring for others and relationships. She suggests, then, that in order to truly measure women’s moral development, it was necessary to create a measure specifically for women. Gilligan was clear that she did not believe neither male nor female moral development was better, but rather that they were equally important.

Think It Over

Consider your own decision-making processes. What guides your decisions? Are you primarily concerned with your personal well-being? Do you make choices based on what other people will think about your decision? Or are you guided by other principles? To what extent is this approach guided by your culture?

Learning and Intelligence

Schools and Testing

When Should School Begin?

In the United States, children generally begin school around age 5 or 6. In fact, most Western countries follow this model. But WHY do we begin school at 5 or 6? For the most part, this age was chosen as a matter of convenience. In countries where the mother is expected to work, the age at which children begin school tends to be younger. That said, research does not support that children should begin formal education so early. Many research studies suggest age 7 is the most appropriate age to begin formalized school. Before age 7, children learn best through play. By age 7, most children are capable of learning in a more formal academic-forward setting.

The Controversy Over Testing In Schools

Children’s academic performance is often measured with the use of standardized tests. Achievement tests are used to measure what a child has already learned. Achievement tests are often used as measures of teaching effectiveness within a school setting and as a method to make schools that receive tax dollars (such as public schools, charter schools, and private schools that receive vouchers) accountable to the government for their performance. In 2001, President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act mandating that schools administer achievement tests to students and publish those results so that parents have an idea of their children’s performance and the government has information on the gaps in educational achievement between children from various social class, racial, and ethnic groups. Schools that show significant gaps in these levels of performance are to work toward narrowing these gaps. Educators have criticized the policy for focusing too much on testing as the only indication of performance levels.

Aptitude tests are designed to measure a student’s ability to learn or to determine if a person has potential in a particular program. These are often used at the beginning of a course of study or as part of college entrance requirements. Originally, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test (PSAT) were billed as aptitude tests, but their makers later dropped “aptitude” from the titles (Strauss, 2014). Other supposed aptitude tests include the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test), the LSAT (Law School Admission Test), and the GRE (Graduate Record Examination). Many of these tests have been criticized as measuring achievement from earlier education as opposed to aptitude or one’s ability to learn. Intelligence tests, like the IQ, are considered a broader form of aptitude tests that were designed to measure a person’s ability to learn. They also face criticism in their ability to accurately measure intelligence.

Theories of Intelligence

Intelligence tests and psychological definitions of intelligence have been heavily criticized since the 1970s for being biased in favor of Anglo-American, middle-class respondents and for being inadequate tools for measuring non-academic types of intelligence or talent. Intelligence changes with experience and intelligence quotients or scores do not reflect that plasticity. What is considered smart varies culturally as well and most intelligence tests do not take this variation into account. For example, in the West, being smart is associated with being quick. A person who answers a question the fastest is seen as the smartest. But in some cultures, being smart is associated with considering an idea thoroughly before giving an answer. A well-thought-out and contemplative answer is the best answer.

Multiple Intelligences

Howard Gardner (1983, 1998, 1999) suggests that there are not one, but nine domains of intelligence. His theory is known as the theory of multiple intelligences. The first three are skills that can be measured by IQ tests:

- Logical-mathematical: the ability to solve mathematical problems; problems of logic, numerical patterns

- Linguistic: vocabulary, reading comprehension, function of language

- Spatial: visual accuracy, ability to read maps, understand space and distance

The next six represent skills that are not measured in standard IQ tests but are talents or abilities that can also be important for success in a variety of fields: These are:

- Musical: ability to understand patterns in music, hear pitches, recognize rhythms and melodies

- Bodily-kinesthetic: motor coordination, grace of movement, agility, strength

- Naturalistic: knowledge of plants, animals, minerals, climate, weather

- Interpersonal: understand the emotion, mood, motivation of others; able to communicate effectively

- Intrapersonal: understanding of the self, mood, motivation, temperament, realistic knowledge of strengths, weaknesses

- Existential: concern about and understanding of life’s larger questions, meaning of life, or spiritual matters

Gardner contends that these are also forms of intelligence. A high IQ does not always ensure success in life or necessarily indicate that a person has common sense, good interpersonal skills, or other abilities important for success.

Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

Another alternative view of intelligence is presented by Sternberg (1997; 1999). Sternberg offers three types of intelligence, known as the triarchic theory of intelligence. Sternberg was concerned that there was too much emphasis placed on aptitude test scores and believed that there were other, less easily measured, qualities necessary for success in higher education and in the world of work. Aptitude test scores indicate the first type of intelligence—academic, or analytical.

- Analytical (componential): includes the ability to solve problems of logic, verbal comprehension, vocabulary, and spatial abilities.

Sternberg noted that students who have high academic abilities may still not have what is required to be a successful graduate student or a competent professional. To do well as a graduate student, he noted, the person needs to be creative. The second type of intelligence emphasizes this quality.

- Creative (experiential): the ability to apply newly found skills to novel situations.

A potential graduate student might be strong academically and have creative ideas, but still be lacking in the social skills required to work effectively with others or to practice good judgment in a variety of situations. This common sense is the third type of intelligence.

- Practical (contextual): the ability to use common sense and to know what is called for in a situation.

This type of intelligence helps a person know when problems need to be solved. Practical intelligence can help a person know how to act and what to wear for job interviews, when to get out of problematic relationships, how to get along with others at work, and when to make changes to reduce stress.

Think It Over

- As an adult, what kind of intellectual skills do you consider to be most important for your success? Consequently, how would you define intelligence?

The World of School

Remember Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model we learned about when we first examined theories of development? This model helps us understand an individual by examining the contexts in which the person lives and the direct (microsystem) and indirect influences (exosystem) on that person’s life. School becomes a very important component of children’s lives during middle childhood and one way to understand children is to look at the world of school. We have discussed educational policies that impact the curriculum in schools above. Now let’s focus on the school experience from the standpoint of the student, the teacher and parent relationship (mesosystem), and the cultural messages (macrosystem) or hidden curriculum taught in school in the United States.

Parents vary in their level of involvement with their children’s schools. Teachers often complain that they have difficulty getting parents to participate in their child’s education and devise a variety of techniques to keep parents in touch with daily and overall progress. For example, parents may be required to sign a behavior chart each evening to be returned to school or may be given information about the school’s events through websites and newsletters. There are other factors that need to be considered when looking at parental involvement. To explore these, first ask yourself if all parents who enter the school with concerns about their child are received in the same way? If not, what would make a teacher or principal more likely to consider the parent’s concerns? What would make this less likely?

Lareau and Horvat (2004) found that teachers seek a particular type of involvement from particular types of parents. While teachers thought they were open and neutral in their responses to parental involvement, in reality, teachers were most receptive to support, praise, and agreement coming from parents who were most similar in race and social class with the teachers. Parents who criticized the school or its policies were less likely to be given a voice. Parents who have higher levels of income, occupational status, and other qualities favored in society have family capital. This is a form of power that can be used to improve a child’s education. Parents who do not have these qualities may find it more difficult to be effectively involved. Lareau and Horvat (2004) offer three cases of African-American parents who were each concerned about discrimination in the schools. Despite evidence that such discrimination existed, their children’s white, middle-class teachers were reluctant to address the situation directly. Note the variation in approaches and outcomes for these three families:

- The Williams family: This working-class, African-American couple, a minister and a hairstylist voiced direct complaints about discrimination in the schools. Their claims were thought to undermine the authority of the school and as a result, their daughter was kept in a lower reading class. However, her grade was boosted to “avoid a scene” and the parents were not told of this grade change.

- The Irving family: This middle class, African-American couple was concerned that the school was discriminating against black students. They fought against it without using direct confrontation by staying actively involved in their daughter’s schooling and making frequent visits to the school to make sure that discrimination could not occur. They also talked with other African-American teachers and parents about their concerns.

- Ms. Caldron: This poor, single-parent was concerned about discrimination in the school. She was a recovering drug addict receiving welfare. She did not discuss her concerns with other parents because she did not know the other parents and did not monitor her child’s progress or get involved with the school. She felt that her concerns would not receive attention. She requested spelling lists from the teacher on several occasions but did not receive them. The teacher complained that Ms. Caldron did not sign forms that were sent home for her signature.

Working within the system without direct confrontation seemed to yield better results for the Irvings, although the issue of discrimination in the school was not completely addressed. Ms. Caldron was the least involved and felt powerless in the school setting. Her lack of family capital and lack of knowledge and confidence keep her from addressing her concerns with the teachers. What do you think would happen if she directly addressed the teachers and complained about discrimination? Chances are, she would be dismissed as undermining the authority of the school, just as the Masons, and might be thought to lack credibility because of her poverty and drug addiction. The authors of this study suggest that teachers closely examine their biases against parents. Schools may also need to examine their ability to dialogue with parents about school policies in more open ways. What happens when parents have concerns over school policy or view student problems as arising from flaws in the educational system? How are parents who are critical of the school treated? And are their children treated fairly even when the school is being criticized? Certainly, any efforts to improve effective parental involvement should address these concerns.

Student Perspectives

Imagine being a 3rd-grader for one day in public school. What would the daily routine involve? To what extent would the institution dictate the activities of the day and how much of the day would you spend on those activities? Would you always be on task? What would you say if someone asked you how your day went? or “What happened in school today?” Chances are, you would be more inclined to talk about whom you sat at lunch with or who brought a puppy to class than to describe how fractions are added.

Ethnographer and Professor of Education Peter McLaren (1999) describes the student’s typical day as filled with a constrictive and unnecessary ritual that has a damaging effect on the desire to learn. Students move between various states as they negotiate the demands of the school system and their own personal interests. The majority of the day (298 minutes) takes place in the student state. This state is one in which the student focuses on a task or tries to stay focused on a task, is passive, compliant, and often frustrated. Long pauses before getting out the next book or finding materials sometimes indicate that frustration. The street corner state is one in which the child is playful, energetic, excited, and expresses personal opinions, feelings, and beliefs. About 66 minutes a day take place in this state. Children try to maximize this by going slowly to assemblies or when getting a hall pass-always eager to say ‘hello’ to a friend or to wave if one of their classmates is in another room. This is the state in which friends talk and play. In fact, teachers sometimes reward students with opportunities to move freely or to talk or to be themselves. But when students initiate the street corner state on their own, they risk losing recess time, getting extra homework, or being ridiculed in front of their peers. The home state occurs when parents or siblings visit the school. Children in this state may enjoy special privileges such as going home early or being exempt from certain school rules in the mother’s presence, or it can be difficult if the parent is there to discuss trouble at school with a staff member. The sanctity state is a time in which the child is contemplative, quiet, or prayerful. Typically the sanctity state is a very brief part of the day.

Since students seem to have so much enthusiasm and energy in street corner states, what would happen if the student and street corner states could be combined? Would it be possible? Many educators feel concerned about the level of stress children experience in school. Some stress can be attributed to problems in friendship. And some can be a result of the emphasis on testing and grades, as reflected in a Newsweek article entitled “The New First Grade: Are Kids Getting Pushed Too Fast Too Soon?” (Tyre, 2006). This article reports concerns of a principal who worries that students begin to burn out as early as 3rd grade. In the book, The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing, Kohn (2006) argues that neither research nor experience support claims that homework reinforces learning and builds responsibility. Why do schools assign homework so frequently? A look at cultural influences on education may provide some answers.

Cultural Influences

Another way to examine the world of school is to look at the cultural values (part of Bronfenbrenner’s macrosystem): the concepts, behaviors, and roles that are part of the school experience but are not part of the formal curriculum. These are part of the hidden curriculum but are nevertheless very powerful messages. The hidden curriculum includes ideas of patriotism, gender roles, the ranking of occupations and classes, competition, and other values. Teachers, counselors, and other students specify and make known what is considered appropriate for girls and boys. The gender curriculum continues into high school, college, and professional school. Students learn a ranking system of occupations and social classes as well. Students in gifted programs or those moving toward college preparation classes may be viewed as superior to those who are receiving tutoring.

Gracy (2004) suggests that cultural training occurs early. Kindergarten is an “academic boot camp” in which students are prepared for their future student role-that of complying with an adult imposed structure and routine designed to produce docile, obedient, children who do not question meaningless tasks that will become so much of their future lives as students. A typical day is filled with structure, ritual, and routine that allows for little creativity or direct, hands-on contact. “Kindergarten, therefore, can be seen as preparing children not only for participation in the bureaucratic organization of large modern school systems but also for the large-scale occupational bureaucracies of modern society” (Gracy, 2004, p. 148).

Emphasizing math and reading in preschool and kindergarten classes is becoming more common in some school districts. It is not without controversy, however. Some suggest that emphasis is warranted in order to help students learn math and reading skills that will be needed throughout school and in the world of work. This will also help school districts improve their accountability through test performance. Others argue that learning is becoming too structured to be enjoyable or effective and that students are being taught only to focus on performance and test-taking. Students learn student incivility or lack of sincere concern for politeness and consideration of others is taught in kindergarten through 12th grades through the “what is on the test” mentality modeled by teachers. Students are taught to accept routinized, meaningless information in order to perform well on tests. And they are experiencing the stress felt by teachers and school districts focused on test scores and taught that their worth comes from their test scores. Genuine interest, an appreciation of the process of learning, and valuing others are important components of success in the workplace that are not part of the hidden curriculum in today’s schools.

Think It Over

- Do an online search for “kindergarten schedule” and look for a typical daily schedule. Do you think it includes a healthy amount of learning and play? Why or why not?

- To what extent do you think that students are being prepared for their future student role? What are the pros and cons of such preparation? Look at the curriculum for kindergarten and the first few grades in your own school district.