What are the physical changes that occur during puberty and adolescence?

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls. The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, with the exception of infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean. In this section, you will learn about the pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity, the social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, and some of the health concerns during adolescence, including eating disorders.

Learning Objectives

- Describe pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity

- Explain social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, including sex differences

- Describe brain development during adolescence

- Describe health and sexual concerns during adolescence

- Discuss concerns associated with eating disorders

Physical Development during Adolescence

Puberty Begins

Puberty is the period of rapid growth and sexual development that begins in adolescence and starts at some point between ages 8 and 14. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by genes; however environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence. Especially for girls, body fat and pubertal timing go together; body fat is linked with earlier age of puberty.

Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past. Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. This average age of onset has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013). Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. In fact, the prolonging of adolescence has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000). We’ll learn more about this phase in the next module.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state. The hypothalamus triggers the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the bloodstream and initiates a chain reaction.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth. The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation.

Sexual Maturation

During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop and mature. Primary sex characteristics are organs specifically needed for reproduction—the uterus and ovaries in females and penis and testes in males. Secondary sex characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs, such as the development of breasts and hips in girls, and the development of facial hair and a deepened voice in boys. Both sexes experience the development of pubic and underarm hair, as well as increased development of sweat glands.

The male and female gonads are activated by the surge of the hormones discussed earlier, which puts them into a state of rapid growth and development. The testes primarily release testosterone and the ovaries release estrogen; the production of these hormones increases gradually until sexual maturation is met.

For girls, observable changes begin with nipple growth and pubic hair. Then the body increases in height while fat forms particularly on the breasts and hips. The first menstrual period (menarche) is followed by more growth, which is usually completed by four years after the first menstrual period began. Girls experience menarche usually around 12–13 years old. For boys, the usual sequence is the growth of the testes, initial pubic-hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid (spermarche), appearance of facial hair, a peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic-hair growth (Herman-Giddens et al., 2012). Boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old.

Physical Growth: The Growth Spurt

During puberty, both sexes experience a rapid increase in height and weight (referred to as a growth spurt) over about 2-3 years resulting from the simultaneous release of growth hormones, thyroid hormones, and androgens. Males experience their growth spurt about two years later than females. For girls, the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. Boys begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Before puberty, there are nearly no differences between males and females in the distribution of fat and muscle. During puberty, males grow muscle much faster than females, and females experience a higher increase in body fat and bones become harder and more brittle. An adolescent’s heart and lungs increase in both size and capacity during puberty; these changes contribute to increased strength and tolerance for exercise.

Reactions Toward Puberty and Physical Development

The accelerated growth in different body parts happens at different times, but for all adolescents, it has a fairly regular sequence. The first places to grow are the extremities (head, hands, and feet), followed by the arms and legs, and later the torso and shoulders. This non-uniform growth is the opposite of the proximodistal pattern (center then out) and one reason why an adolescent body may seem out of proportion. Additionally, because rates of physical development vary widely among teenagers, puberty can be a source of pride or embarrassment.

Most adolescents want nothing more than to fit in and not be distinguished from their peers in any way, shape, or form (Mendle, 2014). So when a child develops earlier or later than his or her peers, there can be long-lasting effects on mental health. Simply put, beginning puberty earlier than peers presents great challenges, particularly for girls. The picture for early-developing boys isn’t as clear, but evidence suggests that they, too, eventually might suffer ill effects from maturing ahead of their peers. The biggest challenges for boys, however, seem to be more related to late development.

As mentioned in the Khan Academy video about physical development, early maturing boys tend to be stronger, taller, and more athletic than their later maturing peers. They are usually more popular, confident, and independent, but they are also at a greater risk for substance abuse and early sexual activity (Flannery et al., 1993; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2001). Additionally, more recent research found that while early-maturing boys initially had lower levels of depression than later-maturing boys, over time they showed signs of increased anxiety, negative self-image and interpersonal stress (Rudolph et al., 2014).

Early maturing girls may be teased or overtly admired, which can cause them to feel self-conscious about their developing bodies. These girls are at increased risk of a range of psychosocial problems including depression, substance use, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). These girls are also at a higher risk for eating disorders, which we will discuss in more detail later in this module (Ge et al., 2001; Graber et al., 1997; Striegel-Moore & Cachelin, 1999).

Late-blooming boys and girls (i.e., they develop more slowly than their peers) may feel self-conscious about their lack of physical development. Negative feelings are particularly a problem for late maturing boys, who are at a higher risk for depression and conflict with parents (Graber et al., 1997) and more likely to be bullied (Pollack & Shuster, 2000).

Brain Development During Adolescence

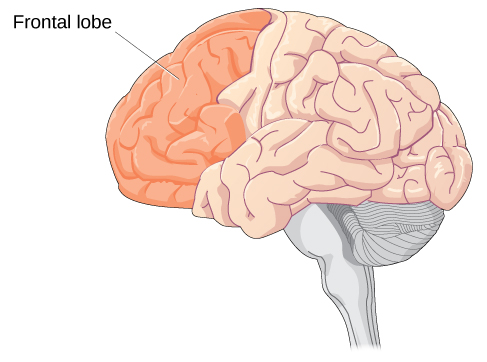

The human brain is not fully developed by the time a person reaches puberty. Between the ages of 10 and 25, the brain undergoes changes that have important implications for behavior. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the time a person is six or seven years of age. Thus, the brain does not grow in size much during adolescence. However, the creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens. The biggest changes in the folds of the brain during this time occur in the parts of the cortex that process cognitive and emotional information.

Up until puberty, brain connections continue to bloom in the frontal region. Some of the most developmentally significant changes in the brain occur in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making and cognitive control, as well as other higher cognitive functions. During adolescence, myelination and synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex increase, improving the efficiency of information processing, and neural connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions of the brain are strengthened. However, this growth takes time and the growth is uneven.

The Teen Brain: 5 Things to Know

As you learn about brain development during adolescence, consider these six facts from The National Institute of Mental Health:

Your brain does not keep getting bigger as you get older

For girls, the brain reaches its largest physical size around 11 years old and for boys, the brain reaches its largest physical size around age 14. Of course, this difference in age does not mean either boys or girls are smarter than one another!

But that doesn’t mean your brain is done maturing

For both boys and girls, although your brain may be as large as it will ever be, your brain doesn’t finish developing and maturing until your mid-to-late-20s. The front part of the brain, called the prefrontal cortex, is one of the last brain regions to mature. It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing, and controlling impulses.

The teen brain is ready to learn and adapt

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience.

Many mental disorders appear during adolescence

All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental disorders—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge.

The teen brain is resilient

Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens go on to become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental disorders.

The limbic system develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. Development in the limbic system plays an important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey et al., 2005).

Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system increase, and input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. The increased dopamine activity in adolescence may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin is involved in the regulation of mood and behavior. It affects the brain in a different way. Known as the “calming chemical,” serotonin eases tension and stress. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behavior can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, it seems that these chemicals interact to balance out extreme behaviors. But when stress, arousal, or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex, and as a result, adolescents engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and emotional outbursts possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing.

Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation. The difference in timing of the development of these different regions of the brain contributes to more risk-taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills that sometimes come from risky behavior, such as reckless driving, smoking, or drinking, and have not yet developed the cognitive control to resist impulses or focus equally on the potential risks (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than are children or adults.

As mentioned in the introduction to adolescence, too many who have read the research on the teenage brain come to quick conclusions about adolescents as irrational loose cannons. However, adolescents are actually making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes, but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in a developmental context. Young people need to somewhat enjoy the thrill of risk-taking in order to complete the incredibly overwhelming task of growing up.

Key Takeaways

In sum, the adolescent years are a time of intense brain changes. Interestingly, two of the primary brain functions develop at different rates. Brain research indicates that the part of the brain that perceives rewards from risk, the limbic system, kicks into high gear in early adolescence. The part of the brain that controls impulses and engages in longer-term perspective, the frontal lobes, matures later. This may explain why teens in mid-adolescence take more risks than older teens. As the frontal lobes become more developed, two things happen. First, self-control develops as teens are better able to assess cause and effect. Second, more areas of the brain become involved in processing emotions, and teens become better at accurately interpreting others’ emotions.

Sleep

Brain development even affects the way teens sleep. Adolescents’ normal sleep patterns are different from those of children and adults: teens need more sleep than children and adults. Teens are often drowsy upon waking, tired during the day, and wakeful at night. Although it may seem like teens are lazy, science shows that melatonin levels (or the “sleep hormone” levels) in the blood naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning in teens than in most children and adults. This is called a phase delay or shift in their circadian rhythms. This may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning. Teens should get about 9-10 hours of sleep a night, but most teens don’t get enough sleep. A lack of sleep makes paying attention hard, increases impulsivity, and may also increase irritability and depression.

Link to Learning: School Start Times

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times.

California recently enacted later start times. Middle schools cannot start before 8:00 a.m., and high schools cannot start before 8:30 a.m. (Associated Press, 2022). This is an important issue to follow as we learn more from research on implementing these changes.

Health During Adolescence

Health Concerns During Adolescence

Nutrition

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development.

One of the reasons for poor nutrition is anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in-person and via social media).

Much research has been conducted on the psychological ramifications of body image on adolescents. Modern-day teenagers are exposed to more media on a daily basis than any generation before them. Recent studies have indicated that the average teenager watches roughly 1500 hours of television per year, and 70% use social media multiple times a day (Markey, 2019). As such, modern-day adolescents are exposed to many representations of ideal, societal beauty. The concept of a person being unhappy with their own image or appearance has been defined as “body dissatisfaction.” In teenagers, body dissatisfaction is often associated with body mass, low self-esteem, and atypical eating patterns. Scholars continue to debate the effects of media on body dissatisfaction in teens. What we do know is that two-thirds of U.S. high school girls are trying to lose weight and one-third think they are overweight, while only one-sixth are actually overweight (MMWR, 2016).

Eating Disorders

Dissatisfaction with body image can explain why many teens, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest diet pills to lose weight and why boys may take steroids to increase their muscle mass. Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2019). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, some men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular.

Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2019). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women. The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). People with anorexia limits food intake, whereas those with bulimia engage in binge and purge cycles: they eat a large amount of food in a short time period and then try to purge those calories to prevent weight gain, often by vomiting or over-exercising. Binge eating disorder was added in 2013 and exhibits the binge cycle without the compensatory purge behavior.

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders

For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increase the risk of heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest death rate of any psychiatric disorder. Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binging and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestive system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol level, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating Disorders Treatment

To treat eating disorders, getting adequate nutrition, and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2019). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding their child. To eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Link to Learning

Visit the National Eating Disorders Association to learn more about eating disorders.

Sexual Development

Developing sexually is an expected and natural part of growing into adulthood. Healthy sexual development involves more than sexual behavior. It is the combination of physical sexual maturation (puberty, age-appropriate sexual behaviors), the formation of a positive sexual identity, and a sense of sexual well-being (discussed more in-depth later in this module). During adolescence, teens strive to become comfortable with their changing bodies and to make healthy, safe decisions about which sexual activities, if any, they wish to engage in.

Earlier in the physical development section, we discussed primary and secondary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, uterus, penis, and testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. During puberty, reproduction becomes possible. Simultaneously, secondary sex characteristics develop. These characteristics are not required for reproduction, but they do signify masculinity and femininity. At birth, boys and girls have similar body shapes, but during puberty, males widen at the shoulders and females widen at the hips and develop breasts (examples of secondary sex characteristics). Sexual development is impacted by a dynamic mixture of physical and cognitive changes coupled with social expectations. With physical maturation, adolescents may become alternately fascinated with and chagrined by their changing bodies, and often compare themselves to the development they notice in their peers or see in the media. For example, many adolescent girls focus on their breast development, hoping their breasts will conform to an ideal body image.

As the sex hormones cause biological changes, they also affect the brain and trigger sexual thoughts. Culture, however, shapes actual sexual behaviors. Emotions regarding sexual experience, like the rest of puberty, are strongly influenced by cultural norms regarding what is expected at what age, with peers being the most influential. Simply put, the most important influence on adolescents’ sexual activity is not their bodies, but their close friends, who have more influence than do sex or ethnic group norms (van de Bongardt et al., 2015).

Sexual interest and interaction are a natural part of adolescence. Sexual fantasy and masturbation episodes increase between the ages of 10 and 13. Masturbation is very ordinary—even young children have been known to engage in this behavior. As the bodies of children mature, powerful sexual feelings begin to develop, and masturbation helps release sexual tension. For adolescents, masturbation is a common way to explore their erotic potential, and this behavior can continue throughout adult life.

Sexual Interactions

Many early social interactions tend to be nonsexual—text messaging, phone calls, email—but by the age of 12 or 13, some young people may pair off and begin dating and experimenting with kissing, touching, and other physical contact, such as oral sex. The vast majority of young adolescents are not prepared emotionally or physically for oral sex and sexual intercourse. If adolescents this young do have sex, they are highly vulnerable to sexual and emotional abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and early pregnancy. For STI’s in particular, adolescents are slower to recognize symptoms, tell partners, and get medical treatment, which puts them at risk of infertility and even death.

Adolescents ages 14 to 16 understand the consequences of unprotected sex and teen parenthood if properly taught, but cognitively they may lack the skills to integrate this knowledge into everyday situations or consistently to act responsibly in the heat of the moment. By the age of 17, many adolescents have willingly experienced sexual intercourse. Teens who have early sexual intercourse report strong peer pressure as a reason behind their decision. Some adolescents are just curious about sex and want to experience it.

Becoming a sexually healthy adult is a developmental task of adolescence that requires integrating psychological, physical, cultural, spiritual, societal, and educational factors. It is particularly important to understand the adolescent in terms of his or her physical, emotional, and cognitive stage. Additionally, healthy adult relationships are more likely to develop when adolescent impulses are not shamed or feared. Guidance is certainly needed, but acknowledging that adolescent sexuality development is both normal and positive would allow for more open communication so adolescents can be more receptive to education concerning the risks (Tolman & McClelland, 2011).

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school, and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behavior, which we discuss in more detail later in this module. Decisions regarding sexual behavior are influenced by teens’ ability to think and reason, their values, and their educational experience. Helping adolescents recognize all aspects of sexual development encourages them to make informed and healthy decisions about sexual matters.