8 III E. Creating OER: Scoping and Drafting

I think authors will surprise themselves with how much they can write each day. I received a summer grant to revise my course and write the textbook. I wrote the text over the summer and set myself a weekly writing goal and then broke down the writing goal by day so I could stay on track. — Caitie Finlayson, Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, University of Mary Washington. Author of World Regional Geography (CC BY NC SA).

People work and write at different paces. Even the same people work and write at different paces, depending on internal and external variables that can change at any time. That said, developing a timeline is an important process for clarifying expectations and ensuring optimal team work. Typical timelines are 3-12 months.

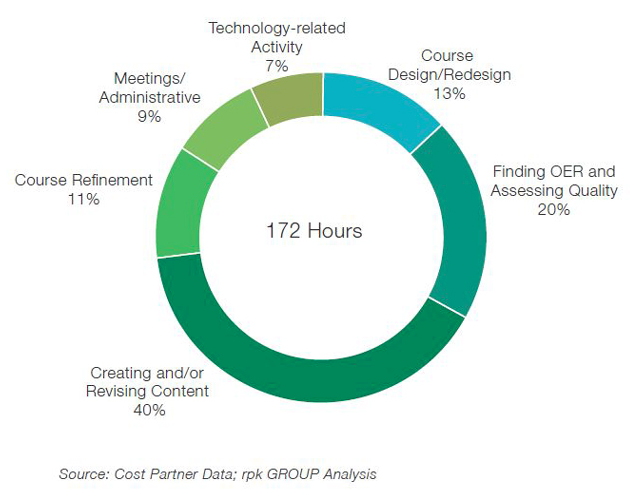

Estimating OER Creation Time

The graphic below illustrates the average time and resources required for creating an open course:

Often the best timelines are created together, between authors and project mangers, working backwards from a deadline. The deadline may be personally set, or determined by the academic calendar, a grant or other external organization. It’s also useful to consult with others you’re working with — freelance editors or proofreaders, for example — to see what their schedules are like and what kind of turn-around time they need.

Sample Timeline

| Date | Completed |

| September 15 | Outline with selected elements and structure identified |

| December 30 | Chapters 1-5 |

| March 15 | Chapters 6-9 |

| March 30 | Submit Manuscript |

| May 1 | Proofreading |

| June 15 | Peer Review |

| July 30 | Revisions |

Of course, what’s included in the timeline is dependent on the project scope and/or author responsibilities.

Ascertaining Project Scope

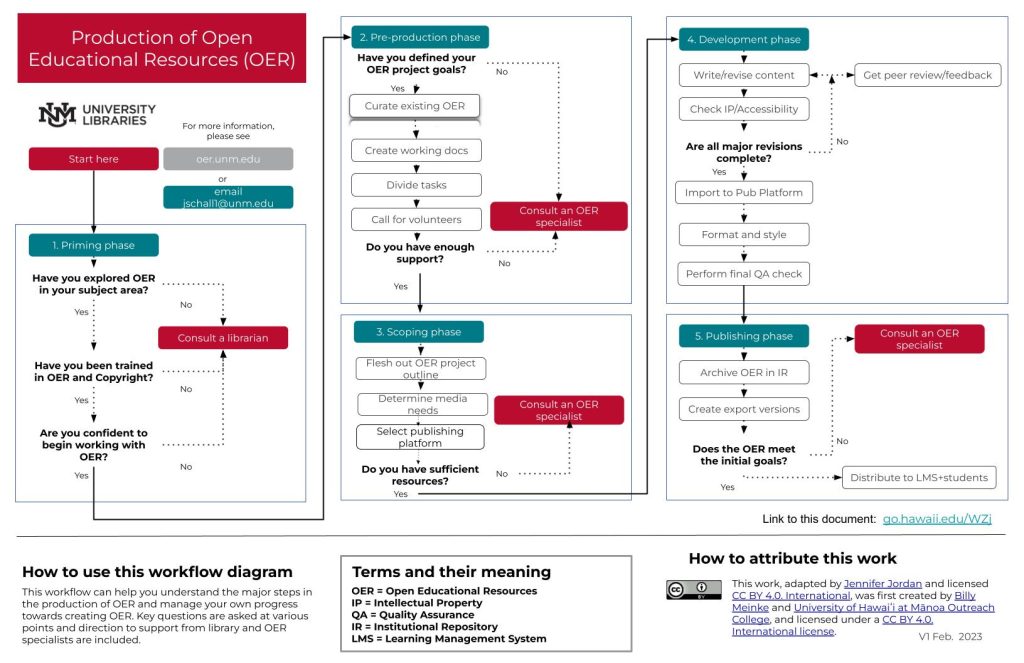

At the beginning of 2016, this OER production workflow was created with the intention of simplifying the major steps in an OER project so that scoping such work would be manageable.

The above image is also available in PDF format to be compatible with screen readers: OER Workflow UNM.

The workflow was shared with the broad OER community via mailing lists and direct appeals to experts in the field, soliciting comments from more than a dozen contributors. It can be useful when performing the initial scoping of an OER project.

Priming

This is the first phase of identifying a timeline and workload for your OER project. Here you can ask key questions about your potential adoption, adaptation, or creation. Once you have completed a basic training or consultation and have performed a cursory search of content that may work for you, you can move onto the next phase.

Pre-production

Before any direct work on content is done, we need to get organized. This means defining the project goals and creating the planning documents you’ll need to manage the process. The linked Timeline Template is a good start for you to organize the work of your project.

The more attention you give toward planning your project the better, and you should use management documents and tools you and your collaborators are familiar with. It is at this point that a call for volunteers (contributors, copyeditors, reviewers) can be sent out if your project would need such support to be successful. Continue in this phase until the necessary resources are secured and commitments have been gathered from collaborators.

Scoping

This phase is the last step before you get our hands dirty with OER. It is here that we flesh out any outlines for the content and confirm major planned revisions of existing OER you have found for the project. If media development (image/video editing, visual design) is a planned need, scoping this work is done here. During this phase you should also determine where you would like your finished OER project to live. Before leaving this phase, you should have a clear idea of both what you are building and how it will get done.

Development

This phase is the real meat of the OER production process — and the most time consuming. It is here that we take existing OER (if applicable) and move it into a shared editing environment to ease the collaborative development of it. It is also during this stage where original content creation happens.

The content will go through a feedback loop where new content is added, comments and clarifications are made, and the changes are revised by the collaborators. Commenting, track changes, and annotation can facilitate this process well, depending on the software used to develop content. As an example, UNM uses Microsoft Sharepoint and Teams for collaborating in the cloud.

Writing a Draft

The first draft is probably the hardest part of making an open textbook. A few hints to get you writing faster:

- Begin with defining learning objectives and key terms. This assures you or your group are writing, very specifically, to set goals and objectives. Decide on key terms and vocabulary early in the drafting process to help with consistency throughout the textbook.

- Draft in a flash. Get your ideas drafted quickly, without formatting. Don’t worry about headings, graphics, or other issues. It may help prevent writer’s block. There will be time to proofread, copyedit and format the book later.

- Create a resource wish list. Keep a list of materials you’d like to include in the book, but haven’t found yet. If you need a break from writing, work on the list.

Group Process

Commonly, open textbooks are authored by a group. This is either by design, as with a curriculum committee, or because of shared interest among colleagues. In either situation, when more than one person is writing, it helps to have clearly defined roles to expedite the process.

- If possible, bring everyone together to launch the project. Brainstorm topics and concepts to define scope and give everyone a voice in the overall product. Having everyone on board early will prevent rework and confusion as the project progresses.

- During the drafting process, work together to identify learning objectives, key terms and potential resources. Doing so assures that everyone is working to the same end.

- Divide the work by defining roles.

Common Group Roles

- Writer: Writes draft with consist voice and tone. Since writing is especially time-consuming, it helps to have a few writers, especially if a group has more than three people.

- Curator: Finds or makes supplemental resources. The writer may request materials from the curator, using the resource wish list.

- Archivist: Documents resources used throughout the book. Works with the writer and curator to manage assets. This person may also check attribution in a final draft, and provide appropriate captions and other related help.

Table 1: Commonly Used OER Hosting Platforms

Digital Repository |

Pressbooks |

Google Docs |

|

|

|

|

|

Publishing

This is the final step in the process of adapting or creating OER. It is at this point that we select the final publishing platform to be used, which through the NM OER Consortium includes the Pressbooks platform, but may be something as simple as a website or course inside the LMS. If print-on-demand and advanced typesetting are needed to complete the project, they are done in this step.

License and Attribution

Creating OER: Scoping and Writing by Jennifer Jordan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License and is adapted from three works:

- Benchmark: Scope an OER Adoption or Creation by William Meinke, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Writing Process by Melissa Falldin and Karen Lauritsen in Authoring Open Textbooks Copyright © 2017 by Open Education Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Developing a Timeline by Melissa Falldin and Karen Lauritsen in Authoring Open Textbooks Copyright © 2017 by Open Education Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

All Rights Reserved Content

Typical Time Required for OER Course Creation, graphic cited from Campus Technology. Data from Achieving the Dream.