Un punto clave en la historia del mundo: El intercambio colombino

Un momento clave en la historia de todos nosotros—incluso los latinos—es el viaje de Cristóbal Colón en el año 1492. Este viaje marca el comienzo del contacto continuo del Nuevo Mundo (las Américas) con el Viejo Mundo (Eurasia y África). El movimiento de personas, productos y organismos que resulta del contacto lleva el nombre de Colón—el intercambio colombino—y cambia el mundo radicalmente para producir la realidad que conocemos hoy.

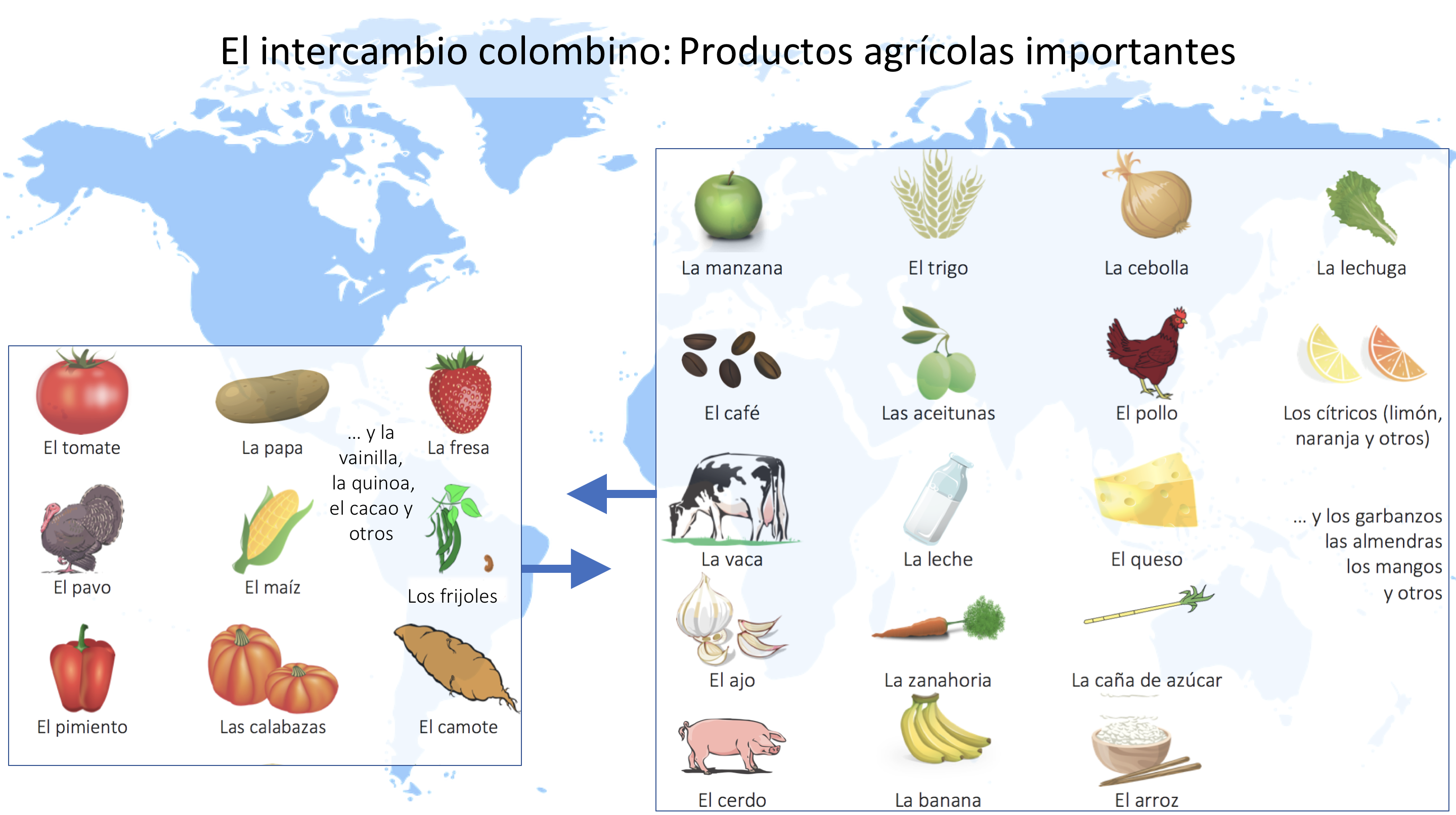

El intercambio colombino y los productos agrícolas

Para nosotros que vivimos en el siglo XXI, es natural identificar las papas con Irlanda o la salsa de tomate con Italia. Pero el origen de estas plantas, como muchas otras, no es obvio. Los europeos y los esclavos africanos que llegan a las Américas traen plantas como la manzana, el trigo, las bananas, los limones, las naranjas, el arroz, el café, la caña de azúcar, las aceitunas y las peras. Desde las Américas al Viejo Mundo van los tomates, los pimientos, las papas, el maíz, el cacao (la planta de donde viene el chocolate), la vainilla, los aguacates, el tabaco y los frijoles. Entre los animales del Viejo Mundo que van al Nuevo Mundo son las vacas, los pollos, los caballos y los cerdos. El único animal doméstico americano que impacta la agricultura en el Viejo Mundo es el pavo. El intercambio de estos productos revoluciona la agricultura y la cocina en el mundo entero.

Entender y usar la materia

Comprensión

These sentences are false. Using what you learned in the reading, correct them. You may not simply write the word “no”.

- El movimiento histórico “intercambio colombino” tiene el nombre del país de Colombia.

- El Viejo Mundo consiste en Europa y África.

- El cacao, los tomates y las papas son plantas del Viejo Mundo.

Eres el profesor

In Spanish, write a five-question quiz about the origin of different foods and agricultural products. Write more than one kind of sentence (yes/no, ¿de dónde?, cierto/falso). Write the answers, too, and then quiz your classmates.

¿De dónde son?

Think of a fruit, vegetable, or grain that you enjoy eating and research its origins. ¿Cómo se llama en español? ¿Es del Nuevo Mundo, del Viejo Mundo o de los dos? Present your findings to the class.

Personalizar la lección

Sobre los gustos no hay nada escrito

The expression “sobre los gustos no hay nada escrito” means that you’re free to like whatever you want, even if I don’t agree with your choice. Can you think of a similar expression in English?

Grammar: Likes and dislikes

To learn how to express likes and dislikes in Spanish, watch the video below: Likes and Dislikes—Gustar

Mis gustos

Using the verb gustar (don’t forget to conjugate it!), write some practice sentences. You’ll find some models below to help you get started.

- Two sentences that tell about foods that you like that originated in the New World: Me gusta el chocolate.

- Two sentences that tell about foods that you like that originated in the Old World: Me gusta el arroz.

- A sentence that tells about a food you don’t like: No me gustan las aceitunas.

- A sentence that compares two foods: Me gustan las naranjas más que los limones.

- A question that asks a classmate about his/her food preferences: ¿Te gustan las naranjas?

Entrevista

Sit with a classmate. Share what you wrote in the previous exercise and write down the answer he/she gives to the question you ask. Then sit with a different person. Tell the new classmate how your first partner answered your question. Hint: When you’re talking about what someone else likes, don’t use me or te. What should you use instead?

Pedir y pagar comida en un restaurante o cafetería

¿Conoces las comidas latinas?

¿Hay un restaurante latino en tu barrio? ¿Comes comida latina? Con tu compañero o compañera de clase, escribe una lista de las comidas latinas que ustedes conocen.

When you are done, take your copy of list that you and your classmate wrote. Go around the classroom to ask other students if they have each of those foods on their list.

Modelos:

Estudiante 1: Tienes guacamole en tu lista?

Estudiante 2: Sí, tengo guacamole. or No, no tengo guacamole.

Estudiante 1: ¿Tienes burritos en tu lista?

Estudiante 2: Sí, tengo burritos en mi lista. or No tengo burritos en mi lista.

¡Delicioso!

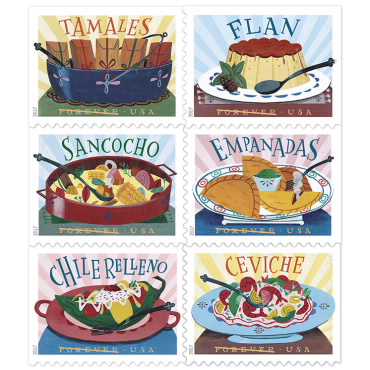

Look at the iconic Latino foods depicted on these United States Postal Service stamps. Tell your group members if you like them, dislike them, or have never tried them.

Modelos:

- Me gustan los tamales.

- No me gusta el flan.

- Nunca probé (I never tried) el sancocho.

Investigación

Work with a group of classmates. Divide up the foods depicted on the Delicioso stamps, research their primary ingredients (en español), and report your findings to your group. Check more than one website or recipe to be sure you’re finding fairly authentic lists of ingredients.

Grammar: Stem-changing verbs

Some verbs have changes in their stems (the stem is the part that’s left over after you take off the -ar, -er, or -ir). Learn about and practice conjugating them by watching the video below: Stem-changing Verbs (present).

Preferencias en el menú

In this conversation with a classmate, you’ll use preferir, recomendar, costar, and querer, which are stem-changing verbs. Take turns asking your partner about his/her menu preferences and the prices on the menu you see below using those verbs.

Modelos:

To practice with nosotros forms, find some things that you and your partner (don’t) want to order.

Modelo: Yo no quiero ordenar ceviche. Tú no quieres ordenar ceviche. Nosotros no queremos ordenar ceviche.

Las preferencias de José

Listen to José A. from México D.F. say what he might order in a Mexican restaurant. Which of the foods that he talks about sounds like it might be a vegetarian dish? Write down the food and beverage words he says that also appear on the menu above.

Recomendaciones para nuestros amigos

Look at the menu again. Suggest an appropriate meal for each of these people and share your ideas with a classmate.

Modelo: A Mikaela le* recomiendo el guacamole y los chiles rellenos y para beber, una cerveza Dos Equis. Para el postre, le recomiendo el flan y el café cubano. ¿Qué recomiendas tú?

- Mikaela no come carne.

- A Mateo le gusta la carne de vaca pero no la carne de cerdo.

- Yesenia no puede comer comida con gluten y prefiere la comida mexicana/tejana.

- Damián no quiere comer mucho.

Comparar las comidas

Write a sentence that compares two different foods on the menu. You can write about their price or how they taste or other aspect you’d like to point out.

Diálogo en un restaurante

With a group of classmates, write a dialogue between a server and customers at El Rincón de doña Rica. Be sure you can say the numbers in Spanish.

Investigación

Select one of these dishes. Research it and create a list of its primary ingredients (en español) and the origin of each one (Nuevo Mundo, Viejo Mundo o los dos): apple pie, beef burrito, Hawaiian pizza, macaroni and cheese, Philly cheesesteak, roast turkey with mashed potatoes. Present what you learned to the class.

Análisis de un poema—“América” por Richard Blanco

In order to gain a fuller understanding of the Cuban-American poet Richard Blanco’s poem “América”, we’ll do a close reading (a detailed and careful observation of word choice, images, and patterns in a text).

Cultural context

Some schools of literary criticism ignore writers and their intentions. But cultural and historical context are valuable tools for gaining a deeper understanding of this poem. Blanco’s family left Cuba, spent a short amount of time in Spain, and arrived in the United States in 1968, when he was a few weeks old. Most of the Cuban exiles in the 1960s were upper- and middle-class political refugees who left everything behind. We’ll also consider what Blanco tells us at the top of the web page for “América”: that Thanksgiving, an “untranslatable” holiday, was one his family never “got”.

- What does Thanksgiving mean to you and the people you celebrate it with?

- What is your usual menu?

- What do you do before and after the meal?

- Compare your answers with those of your classmates. Whose Thanksgiving celebration seems to be the most traditionally American?

Rhyme and meter (versification)

Read the poem out loud and/or listen to Blanco read it on his website. Does the poem have a rhyme scheme? A fixed and regular meter?

Other Poetic Elements

- Plot and characterization

- What is the plot of the poem?

- Who are its characters?

- What words does Blanco choose to develop the characters?

- Imagery

- Mark the three or four places in “América” where the poet’s imagery speaks to you—the places where you feel, see, hear, or smell what he’s expressing.

- Stanza I. In this poem, Blanco contrasts the Cuban and American cultural experiences that run through his childhood.

- What cultural practices and immigration experiences does Blanco show us through his memories of peanut butter?

- Stanza II

- Examine Blanco’s choice of vocabulary carefully, looking up unfamiliar words, cultural and historical references and writing them down to share with your classmates.

- Stanzas III-V

- List the American and the Cuban cultural products (things people make) and practices (things people do) in the poem. Again, look up vocabulary and cultural and historical references to get a full picture.

- Where do the two cultures come together to create positive emotions for the narrator?

- Where do they create negative emotions for him?

- Tone

- Does Blanco’s tone seem comic to you?

- Tragic? Wry? Heroic? A mixture? Something else?

- Discussion and conclusion. A close reading of poetry means reading the poem more than once, circling back to the questions you reflected on earlier on the process, and a final complete read-through.When you’ve finished, consider these questions and be prepared to discuss them in class.

- Is Blanco’s Thanksgiving story and, by extension, his family’s experience at adapting to American culture, in the end, a happy or a sad one?

- What clues from the text support your opinion?

- In what ways is the tension of ni de aquí, ni de allá present this poem?

Mi poema bilingüe

In this first lesson of Unidad 4, we’ve talked about some ways in which the Columbian Exchange contributed to the creation of the modern world and, more specifically, to the creation of our own identities as people who live in the Americas. Richard Blanco’s free verse poem “América” speaks to one aspect of identity—being an immigrant—viewed through the lens of that uniquely North American holiday of Thanksgiving. Now it’s your turn to write an original bilingual poem. You can look for tips on writing free verse poetry at Power Poetry’s website.

The theme for your poem is the same as Unidad 4’s—the identity of people of the Americas as created by the Columbian Exchange. This theme is broad, and you will have to narrow it down. You may choose to write about anything related to the larger unit theme, but if you need some inspiration to get started, here are some ideas.

- Response poem. Copy one of Blanco’s lines that you found important/meaningful/inspiring/irritating. Use it as the first line of your poem and write a response to him.

- A family holiday meal. As is true for Blanco’s, your family’s celebrations are mirrors of your culture. Tell a story of your family’s culture in a holiday meal.

- Deconstruction of a food. In Unidad 4, we explored some traditional foods—mac and cheese, pizza, apple pie—whose roots are a complicated mix of Old World and New World, roots that grow from a history of conquest. Write a poem where you take apart or put together a favorite food by examining its roots.

- Then and now. In the early 1960s, the United States admitted 58,000 people who, like Blanco, were refugees from Cuban communism. The number admitted for the year 2020 is a maximum of 18,000. America is a nation of immigrants—some of them refugees themselves—yet we as a population have a history of not being very accepting of them. Write a poem that is a conversation between Blanco and a refugee seeking entry into the United States.

- A new Thanksgiving. Write a poem in which you make a twist on the traditional holiday menu to reflect the past or future of the United States.

After completing this theme, I can ...

- in Spanish, list some common agricultural products and indicate their origin (Old World vs. New World).

- in Spanish, describe the Columbian exchange and how it impacted food and agriculture.

- in Spanish, express and ask about food preferences.

- in Spanish, identify a few traditional dishes of the Spanish-speaking world and their ingredients.

- make recommendations in Spanish in simple ways.

- order food from a Spanish-language menu.

- interpret a bilingual poem about the Latino experience.

- express, in an original bilingual poem, how my own identity is influenced by the Columbian exchange.