Social Interaction in CALL

Social interaction may take place in many configurations—for example, student to student, student to group, and group to group. Learners can also interact socially with a variety of people: classmates, teachers, students in other classes, community members, external experts, and peers around the world. Sometimes they may be part of a massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) (either educational or “serious”), where they randomly join and collaborate towards a shared goal. However, because learners are part of groups or asked to participate does not mean that they will interact, or that they will interact in the target language, or that the interaction will facilitate language learning. The teacher must plan carefully to ensure that the interaction is effective.

The following video analyzes an advanced example of social interaction in CALL. It reveals how a multimedia online game facilitates learning and socialization for learners of a second language.

Here are two techniques for helping teachers to develop tasks that increase the possibility of quality social interaction:

-

Provide opportunities for learners to be active.

We have all been in study groups in which some students do the work and others do not participate. Those who do not participate may acquire some of the task’s language or content, but they may also be missing out on the interaction they need to succeed. To help students become actively involved in the interaction, the teacher can build specific roles or assignments for individuals into tasks so that each student’s contribution is necessary to achieve the group or team goal. These activity structures create the need for students to interact in the target language; the more learners need to interact, the more effective the interaction should be. These principles are the basis of techniques such as cooperative learning, jigsaw, and information gap (Burns, & Richards, 2009; Kagan, 1994; Richards & Lockhart, 1994; Peregoy & Boyle, 2017).

-

Provide Reasons For Learners To Listen And Respond.

Many times at the end of a group task, learners are required to present their products to the whole class. In reality, they are addressing their presentations to the teacher for evaluation. What reason do the other students have to attend to what is being presented? By providing reasons to listen, such as adding evaluation rubrics that the audience completes, providing a handout to take notes for a quiz, or requiring a group synthesis of the information presented, the teacher encourages all learners to listen and provides a basis from which to respond.

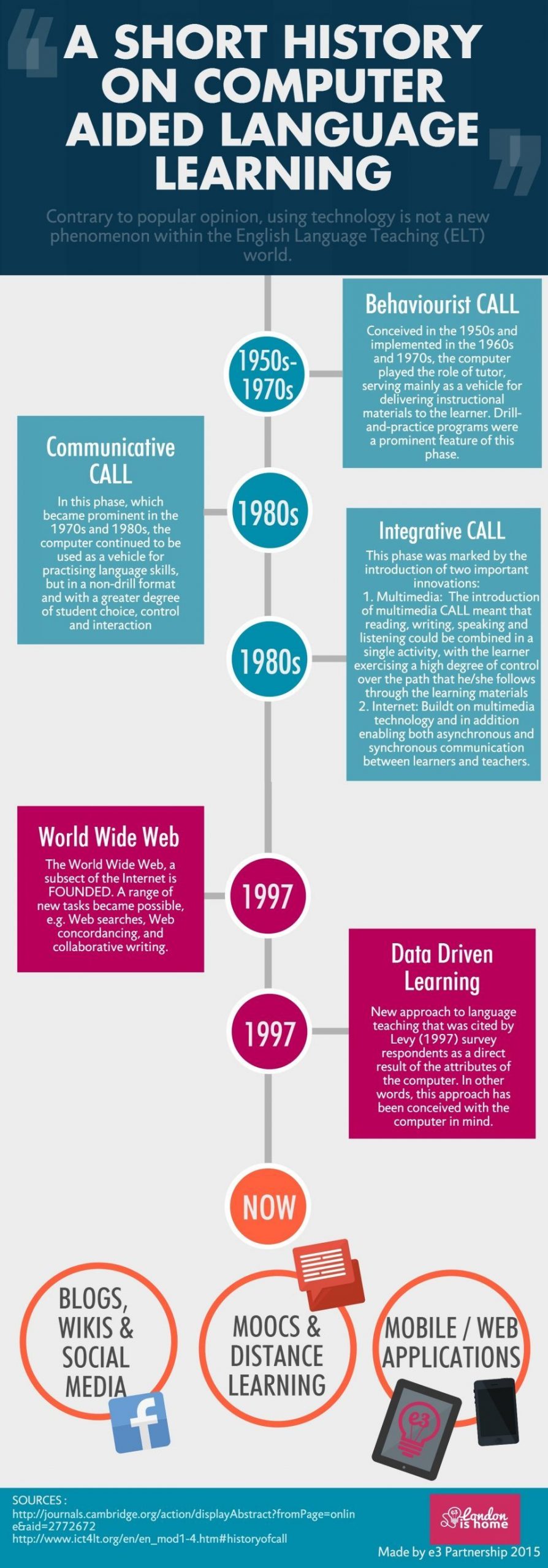

Consider the following infographic, which illustrates how CALL practices have evolved alongside technology to provide more opportunities for students to respond, interact, and engage with each other, the instructor, and the content.

Interaction in the Computer Lab

In a traditional CALL lab layout, students are sequestered in their own carrels or are sitting behind the computers, which obstruct clear lines of sight to the rest of the room. Although labs seem to be falling out of fashion in some contexts, they are useful not only for individual language learning activities such as using self-access software, conducting research, writing papers, sending e-mail, and completing practice exercises, but also for working on individual tasks as part of collaborations with online partners. However, the limited opportunities for mobility and difficulties in sharing hardware in a lab setting can make collaborating face-to-face difficult for multiple learners; this setting is better used, then, for individual tasks or online collaboration.

Interaction in the Multiple-Computer Classroom

Computer classrooms, such as the one shown in Figure 4.1, allow for more group configurations and activities than traditional labs do. In this type of classroom, where computer monitors are recessed into desks and the desks are arranged in pods, students have free lines of sight to each other and an unobstructed view of the teacher. Unlike the lab, students have room to work without the computer and use it only when and if they need it. In this setting, the technology serves as a tool for all kinds of exercises, from building Web pages to creating portfolios to working with stand-alone software packages. Instructors in these settings can develop CALL tasks during which learners work with partners online and face-to-face. It is important to try out the furniture before buying it—not all desks are made the same, and buying the wrong furniture can be a pricey mistake.

Check your learning

Go to our class Voice Thread and watch/listen to the slides your classmates have recorded. Create a response slide/narration that builds on the conversation on this topic, bringing in at least one new idea or thought.

References

History of Computer Aided Language Learning Infographic by E-learning Infographics is included on the basis of fair use as described in the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Open Education

Media Attributions

- CALL Classroom recessed monitor

- CALL classroom active learning

- fairuseoer

an online game with large numbers of players, often hundreds or thousands, on the same server