10

Donna Giuliani, Delta College, Ron Hammond and Paul Cheney-Utah Valley University

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter you will be able to do the following.

- Define divorce

- Analyze divorce trends

- Define marital entropy

- Apply Social Exchange Theory to divorce choices

- Explain Levinger’s Model of Rational Choice for Divorce

- Recall actions that minimize the risk of divorce

Definitions

Divorce is the legal dissolution of a previously granted marriage.

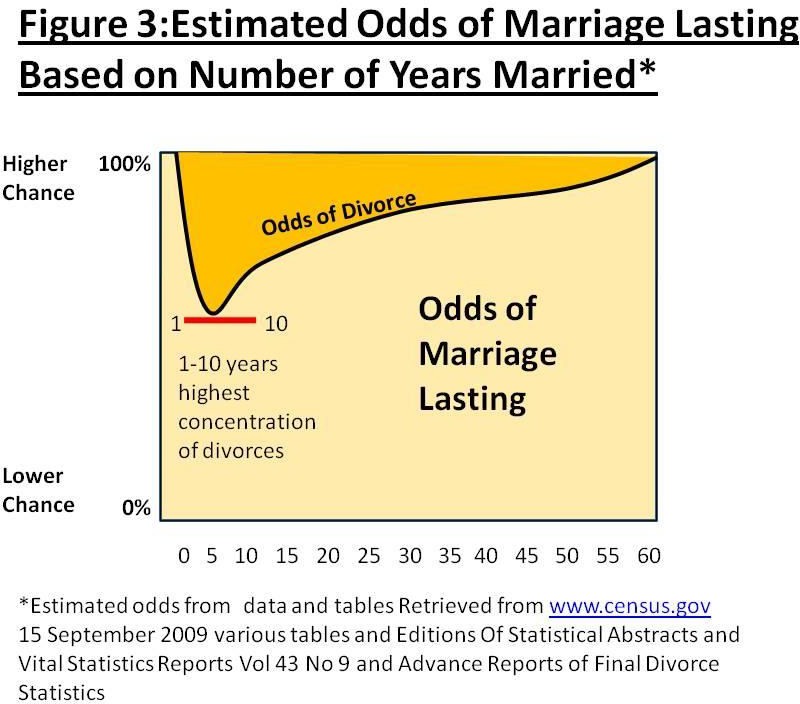

Most marriages still endure, and the odds are that divorce won’t happen to most marriages. It is a myth that one in two marriages eventually ends in divorce. There are a few myths about U.S. divorce trends that will be dispelled in this chapter. You might have heard the myth of the Seven-Year Itch where divorce happens prior to or shortly after the 7th year.

Current government estimates indicate that about 75% of couples make their ten-year anniversary in their first marriage.1 The myths are false, but divorce does happen more today than it did 50 years ago and more people today are currently divorced than were currently divorced 50 years ago.

We’ll discuss these trends in divorce rates below, but first we must define cohort. A Cohort is a group of people who share some demographic characteristic, typically a year such as their birth year or marriage year. The Baby Boom is a cohort of those born between 1946 and 1964 and represented a never before nor never repeated high period of birth rates that yielded about 70 million living Baby Boomers today.

There are few different rates for measuring divorce. The most common divorce rate used by the U.S. Census Bureau is the number of divorces/1,000 population. Another divorce rate is the number of divorces/1,000 married women. The divorce rate that most hear about is the predictive divorce rate which is the percent of people who had married in a given year who will divorce at some point before death. The National Center for Health Statistics reported that in 2001, 43% of marriages break up within the first 15 years of marriage.2 That was the highest official scientifically-based divorce risks estimate ever reported. So for example of those who married in the year 2001, about 43% are predicted to divorce at some point before their 15th anniversary. It is estimated that close to half of them will divorce before one of them dies.

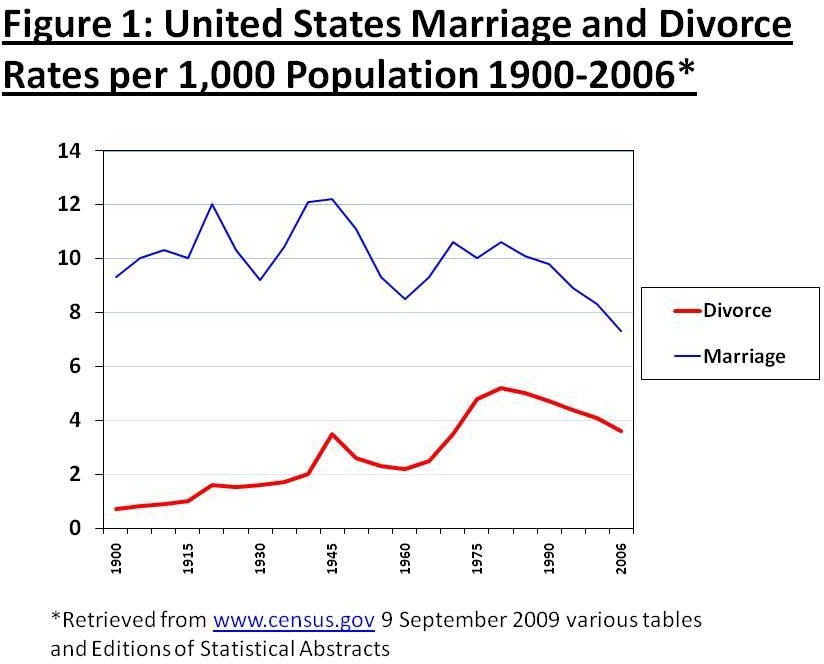

Figure 1 shows the United States marriage and divorce rates/1,000 population from 1900 to 2006. Notice that divorce rates have always been much lower than marriage rates in the U.S. Also notice that marriage and divorce rates moved in very similar directions over the last century. A slight rise is visible after both WWI and WWII ended (1919 and 1946). A slight decline is visible during the Depression (1930s) and turbulent 1960s. Most importantly notice that both marriage and divorce rates have been declining in the 1990s and 2000s. Younger people today are waiting to marry until their late twenties (delayed marriage) while cohabiting has increased in the U.S.

Figure 1 also shows the trends in ratio of divorces to marriages for the U.S. In 1900 there was 1 divorce per 13 marriages that year or 1:13; in 1930, 1:6; in 1950, 1:4; in 1970, 1:3;

1980, 1:2; 1990, 1:2; and 2006, 1:2. Today, that means that every year there are two state sanctioned legal marriages with only one state-sanctioned legal dissolution of a marriage. For the last 12 months ending in December 2008 there was a marriage rate of 7.1 marriages for every 1,000 population and a divorce rate of 3.5 divorces for every 1,000 population. That translates to over 2.1 million marriages and about 1 million divorces in 2008.

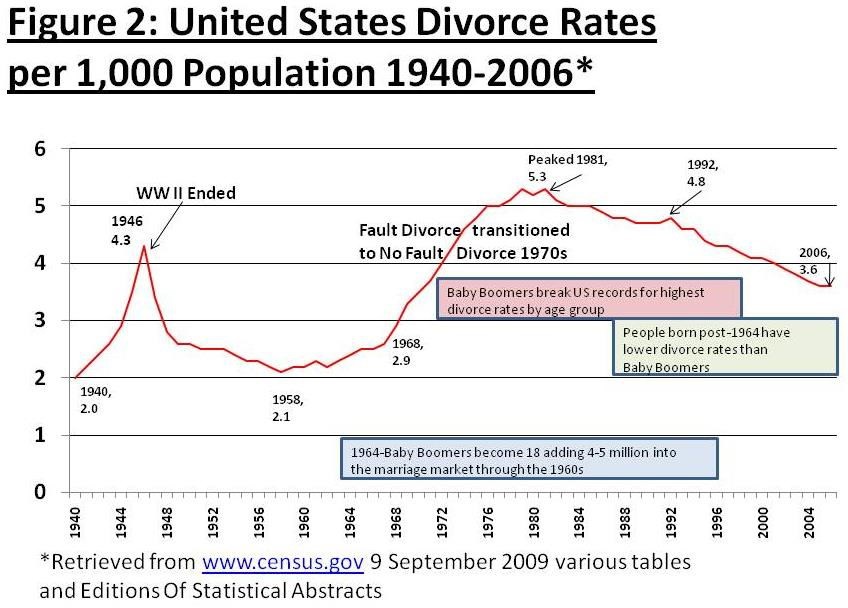

Figure 2 shows a more detailed description of U.S. divorce rates since 1940 and some of the factors that contributed to them. As you already noticed in Figure 1, divorce rates were relatively low prior to 1940. But, in the 1940s WWII was ongoing and divorce rates moved upward with a spike in 1946. Keep in mind that 1946 was the United States’ most unusual year for family-related rates. Divorce rates, marriage rates, birth rates, and remarriage rates surged during this year while couples married at their lowest median age in U.S. history.

After 1946, divorce rates fell to steady low levels and remained there until the 1960s when they slowly began to rise. The Baby Boomers directly and indirectly influenced the rise of divorce rates. In 1964 the first among the Baby Boomers became 18 and entered the prime marriage market years. For the next two decades Baby Boomers added about four million men and women to the marriage market each year. Thus, Baby Boomers raised the numbers of married people and thereby the numbers at risk of divorcing.

Figure 1: United States Marriage and Divorce Rates per 1,000 Population 1900-2006*

Figure 2: United States Divorce Rates per 1,000 Population 1940-2006*

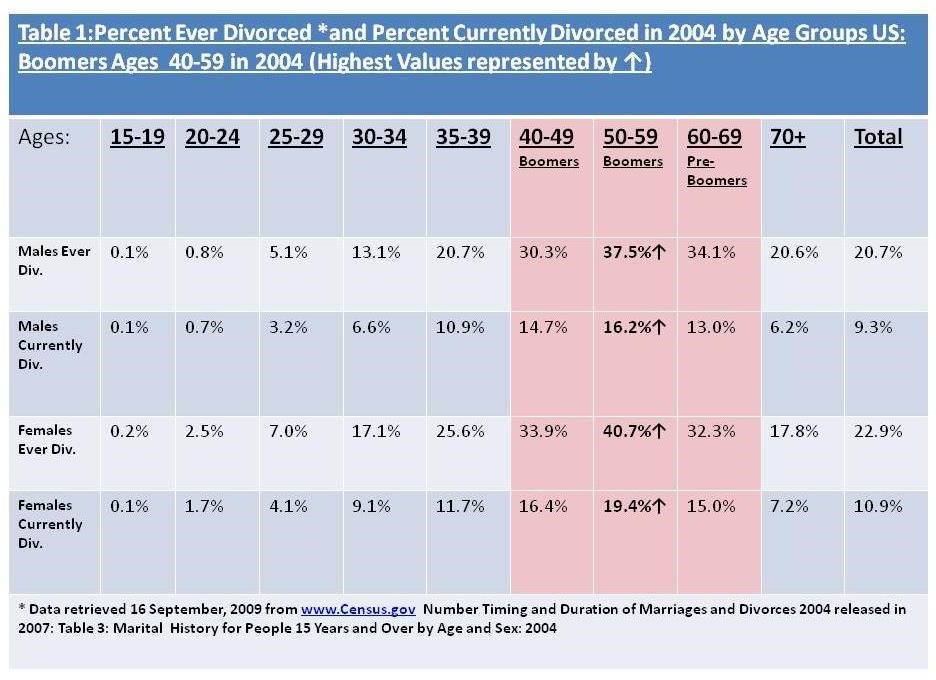

Directly, Baby Boomers contributed to the divorce rate. Baby Boomers and those immediately preceding them (born 1936-1945) have very high rates of divorce. Table 1 shows that the experience of ever having divorced is not directly related to age. In other words, the oldest members of society have not divorced the most. In fact, it is the Baby Boomers and Pre-Baby Boomers who divorced the most followed by the oldest and then the younger cohorts. Thesymbol in Table 1 signifies the highest ever divorced rates. This is in the 50-59 year old cohort (these are Baby Boomers born 1946-1955). The highest currently divorced rates also found among the women and men of the 50-59 cohort. The Baby Boomers 1946-1955 still hold the highest divorce rates by any cohort in U.S. history. Their unprecedented high divorce rates raised the overall divorce rates for the entire nation.

When scientists and government researchers predict the risk you might have of divorcing they use the experiences of currently married people who have and have not divorced— therein lies part of the complication of deriving an “odds or risks of divorce” that we can have confidence in enough to offer advice to the soon-to-be-married . The U.S. has had its worst divorcing cohort ever and some of them will likely divorce again before their death. The trend among younger marrieds is to remain married longer and divorce less, but what if they collectively have an increase in their marital dissolution experiences? What if all of a sudden, millions of currently married couples flock to the courthouse to file for divorce?

First, that scenario isn’t likely to happen because today’s married couples tend to remain married. Second, and this is more important, the national risk of divorce is different from your personal risk of divorce in one crucial factor—you have a great deal of influence in your own marriage quality and outcome. You and your spouse have much control over your marital experience, how you enhance it, how you protect it from stressors that can undermine it, and finally how you maintain it.

Family scientists refer to marital entropy as the principle based on the belief that if a marriage does not receive preventative maintenance and upgrades it will move towards decay and break down. Hearing an evening news report on national divorce trends has much less impact on your marriage than a relaxing weekend away together to recharge your romance and commitment which is a marital maintenance strategy designed to combat marital entropy. A proactive and assertive approach to your marital quality is far more influential than most other factors leading to divorce.

The longer a couple is married the lower their odds of divorce. Figure 3 shows a visual depiction of how the odds of divorce decline over time. The first three years of marriage require many adjustments for newlyweds. Of special mention is the process of transitioning into a cohesive couple relationship with negotiated financial, sexual, social, emotional, intellectual, physical, and spiritual rules of engagement. Most couples have many of these negotiations in place by years 7-10. Since longevity of a marriage is often associated with the arrival of children, accumulation of wealth, establishment of acceptable social status (being married is still highly regarded as a status), and the buffering of many of life’s daily stressors the average couple finds it difficult and too costly to divorce, even though some features of the marriage are less than desirable.

Theories of Divorce

Using Social Exchange Theory as a basis for understanding why couples stay married or divorce, you begin to see that spouses consider the cost- tobenefit ratio; they look at rewards minus punishments, and they weigh the pros and cons in their decisions. Social Exchange Theory claims that society is composed of ever present interactions among individuals who attempt to maximize rewards while minimizing costs. Assumptions in this theory are similar to Conflict Theory assumptions yet have their interactionist underpinnings. Basically,

human beings are rational creatures capable of making sound choices when the pros and cons of the choice are understood. This theory uses a formula to measure the choice making processes (REWARDS-COSTS) = OUTCOMES. This can be translated to what I get out of it minus what

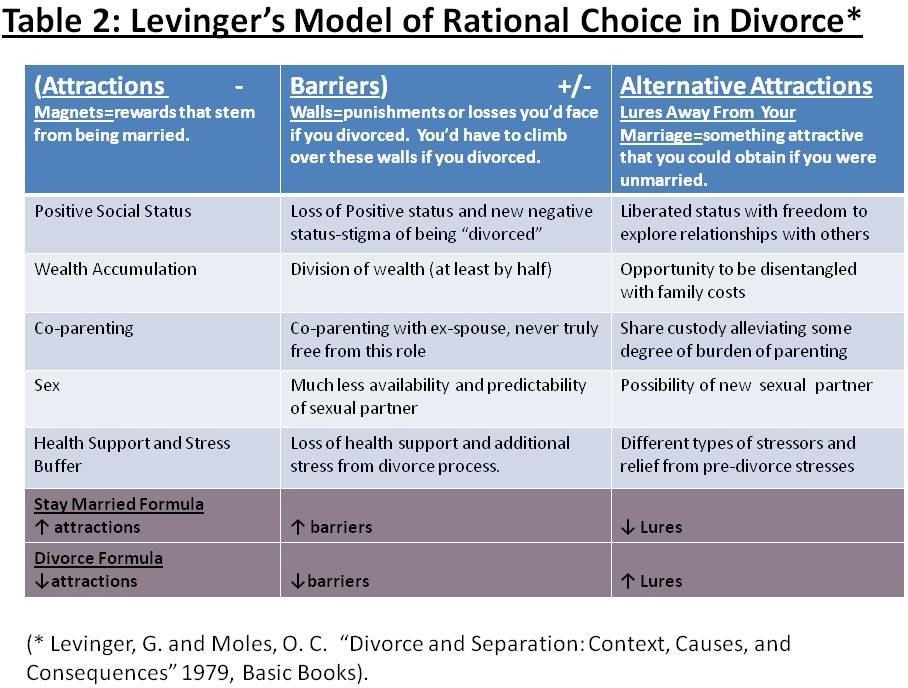

I lose by doing it equals my decision. In 1979 Levinger and Moles published their model wherein they discussed the rational choices made by spouses who were considering divorcing or remaining married. It’s been referred to as Levinger’s Model. Levinger’s Model is Attractions-Barriers +/- Alternative Attractions = My Decision to Stay Married or Divorce. Table 2 below shows an example of how Levinger’s Model clarifies the choices people might make and their perceived rewards and costs.

In Table 2 you see that Levinger’s Attractions are simply the magnets that draw you to the marriage or rewards that stem from being married. These are the payoffs that come from being married and include positive social status, wealth accumulation, co-parenting, sexual intercourse, health support and stress buffer that marriage typically brings to each spouse, as well as others. Each individual defines his or her own attractions. Levinger’s Barriers are simply the costs or punishments that might be incurred if a married person chose to divorce. These might include losing all the attractions and magnets, changing to a negative status, suffering a division of wealth, co-parenting at a distance and without samehousehold convenience, experiencing a change/decline in sexual frequency and predictability, losing the health and stress buffer that married couples enjoy (even unhappily married couples experience some measure of this buffer), and others. Each individual defines his or her own barriers.

Levinger’s Alternative Attractions are basically lures or something appealing that nowmarried spouses might find rewarding if they divorce. These might include liberation and the freedom that comes from being single (albeit divorced) and newly available on the market, a financial disentanglement from ex-spouse and at times child care (especially common view held among men who often share custody but pay less in the end for their children), alleviation of parenting when children are with other parent, freedom from unwanted sexual demands and or possibility of new sexual partner or partners, the abandonment of overbearing stressors from marriage, as well as others. Of course each individual defines his or her own alternative attractions.

The last two rows in Table 2 show how you can use a formula to understand the propensity a couple has to divorcing or staying married. In the Stay Married formula, the attractions and barriers are high while the lures are low. Translated into Social Exchange thinking— there are many rewards in the marriage, with many barriers that would prove more punishing if a spouse wanted to divorce. At the same time there are few lures that might draw a spouse away from their marriage.

The divorce formula is also revealing. Attractions are low, barriers are low, and lures are high. In other words, there are few rewards from being married, low barriers or low perceived punishments from divorcing, with high lures to draw a spouse away from the marriage. One would expect satisfied couples to have the “stay married” formula while dissatisfied couples would have the “divorce formula.” By the way, the formula is only descriptive and not predictive (it cannot tell you what an individual couple might do).

Some with the divorce formula in place remain married for years. A few with the stay married formula become dissatisfied and begin focusing on lures.

One Social Exchange principle that clarifies the rational processes experienced by couples is called the concept of equity. Equity is a sense that the interactions are fair to us and fair to others involved by the consequences of our choices. For example, why is it that women who work 40 hours a week and have a husband who also works 40 hours a week do not perform the same number of weekly hours of housework and childcare? Scientists have surveyed many couples to find the answer. Most often it boils down to a sense of fairness or equity. She defines it as her role to do housework and childcare, while he doesn’t; because they tend to fight when she does try to get him to perform housework and because she may think he’s incompetent, they live with an inequitable arrangement as though it were equitable.

What Predicts Divorce in the U.S.?

Years of research on divorce has yielded a few common themes of what puts a couple at more or less risk of divorce. Everyone is at risk of divorcing, but the presence of divorce risks does not determine the certain outcome of divorce for everyone. There is a geography factor of U.S. divorce. Divorce rates tend to be lower in the North East and Higher in the West. Nevada typically has the highest of all state divorce rates, but is often excluded from comparison because of the “Vegas marriage” or “Vegas divorce” effect.

Simply enduring the difficult times of marriage is associated with remaining married. Most of the factors that contribute to divorce lie to a great extent within the realm of influence and choice had by the individual. For example, waiting until at least your 20th birthday to marry lowers divorce risks tremendously. In fact the best ages to marry are 25-29 (interestingly, the U.S. median age at marriage for men and women falls within this age group). Being younger than 19 years old at your first marriage is extremely risky. Why?

Basically the explanation is that most younger couples are disadvantaged economically, socially, and emotionally, and their circumstances have accompanying hardships that would not be present had they waited to age 25 (for example, had they graduated college first and prepared themselves for the labor force and for the emotional complexity of marriage). Many scientific studies indicate that there is a refining process of social and intellectual capacities that is not reached until around age 26 and those who marry young exchange their prime years of self-discovery for marriage. Another major individual choice-related factor is marrying because of an unplanned pregnancy. Most babies born in the U.S. are born to a married couple. But, today about 40% are born to single mothers of all ages. Even though many of these single mothers marry the baby’s father, numerous studies have indicated that they have a higher likelihood of their marriage ending in divorce.

Many individuals struggle to completely surrender their single status. They mentally remain on the marriage market in case “someone better than their current spouse comes along.” Norval Glenn argued that many individuals see marriage as a temporary state while they keep an eye open for someone better. “More honest vows would often be “as long as we both shall love” or “as long as no one better comes along.” Glenn gets at the core of the cultural values associated with risks of divorcing.4 These values have changed over time.

As more people wanted to divorce, divorce laws became more lax and as the laws loosened, more people were able to divorce.

Robert and Jeanette Lauer are a husband-wife team who studied commitment and endurance of married couples. They identified 29 factors among couples who had been together for 15 years or more. They found that both husbands and wives reported as their number one and two factors that their spouse was their best friend and that they liked their spouse as a person.5 The Lauers also studied the levels of commitment couples had to their marriage. The couples reported that they were in fact committed to and supportive of, not only their own marriage, but marriage as an institution. Irreconcilable differences are common to marriage, and the basic strategy to deal with them is to negotiate as much as is possible, accept the irresolvable differences, and finally live happily with them.

COMBATING DIVORCE

A positive outlook for your marriage as a rewarding and enjoyable relationship is a realistic outlook. Some couples worry about being labeled naïve if they express the joys and rewards their marriage brings to their lives. Be hopeful and positive on the quality and duration of your marriage, because the odds are still in your favor. You’ve probably seen commercials where online matchmaking websites strut their success in matching people to one another. There are websites, along with DVDs, CDs, self-help books, and seminars for marital enhancement available to couples who seek them.6

Doomed, soaring divorce rates, spousal violence, husbands killing wives, decline of marriage, and other gloomy headlines are very common on electronic, TV, and print news stories. The media functions to disseminate information and its primary goal is to make money by selling advertising. The media never has claimed to be scientific in their stories. They don’t really try to represent the entire society with every story. In fact, media is more accurately described as biased by the extremes, based on the nature of stories that are presented to us the viewers. Many media critics have made the argument for years that the news and other media use fear as a theme for most stories, so that we will consume them. Most in the U.S. choose marriage and most who are divorced will eventually marry again.

True, marriage is not bliss, but it is a preferred lifestyle by most U.S. adults. From the Social Exchange perspective, assuming that people maximize their rewards while minimizing their losses, marriage is widely defined as desirable and rewarding. There are strategies individuals can use to minimize the risks of divorce (personal level actions). Table 3 lists ten of these actions.

Table 3. Ten Actions to Minimize the Risk of Divorce.

- Wait until at least 20 years old to marry, 25 is better.

- Don’t marry just because of a pregnancy.

- Become proactive in maintaining your marriage (spend time with your partner).

- Understand risks of cohabitation (cohabitation ≠ divorce).

- Learn to compromise with each other. Work around those irreconcilable differences.

- Keep a positive outlook and look beyond today.

- Take your time in selecting a mate. Don’t rush into marriage.

- Focus on the positive benefits of being married and don’t dwell on the negatives.

Up until the 1990’s decades of studies had indicated that those who ever have cohabited had a higher likelihood of divorce. Cohabitation has been studied especially in contrast between cohabiting and married couples. That trend was, in part because people who cohabited were the exception to the rule. Now however, with most people cohabiting at some point in their lives, cohabitation is no longer a predictor of divorce. Now it is important to consider the characteristics of cohabiters.

- If a couple gets engaged, cohabitants, and then weds, it is not more likely that divorce will occur.

- If a couple is in a long term relationship, cohabitants, gets engaged, and then weds, it is not more likely that divorce will occur.

- If a couple cohabitants quickly and then marries because it is the casual next step, divorce is more likely.

- If someone is a serial cohabiter (going from one live-in relationship to the next), divorce is more likely.

Cohabitation is more common in the U.S. today than ever before. Cohabiters are considered to be unique from those who marry in a variety of ways, yet the similarities between married and cohabiting spouses suggests that their lifestyles overlap. In both lifestyles, relationships are formed and often ended. Cohabiters have more than twice the risks of their relationship ending than do marrieds.8

Children and Divorce

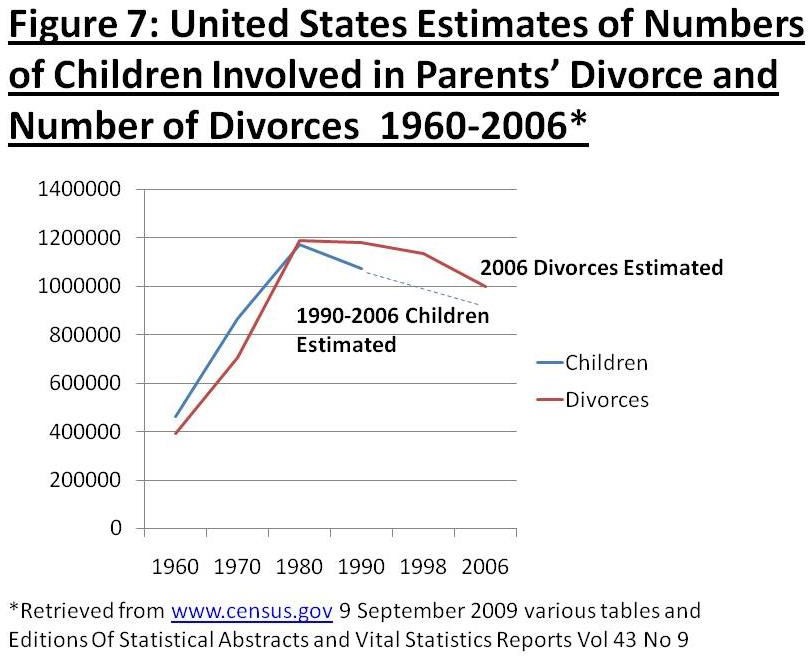

Andrew Cherlin discussed the uniqueness of cohabiting versus married couples. In sum, cohabiters often feel financially ill-equipped to marry, have lower expectations of relationship satisfaction than do marrieds, and often expect a shorter relational duration than marrieds. Cherlin’s main thesis is the stability for children when adult intimate relationships end and his concern is well grounded in the statistics of divorce. Figure 7 (there is no figure 4, 5, or 6) shows that millions of U.S. children have experienced their parents divorces since 1960 with nearly one million children experiencing their parents’ divorce each year.

Let’s think for a minute about what is best for children in terms of their parents remaining married or divorcing. Every home should provide a safe, loving, and nurturing environment where basic needs are met and where children are nurtured into the greatness of their potential. Sounds ideal, right? But, that’s not the real-world experience of most children. Familial stresses and hardships are the norm. Being a child of divorced parents does not imply that you are in some way worse off than children whose parents remain married.

Divorce is a blessing/positive life change for many children and their parents. In fact, some children of divorce are very happily married in their own adult relationships because of their sensitive searching for a safe and compatible partner and because they don’t want their children to suffer as they themselves did. At the same time, having a parent who divorced probably increases the odds of divorce for most children. Judith Wallerstein has followed a clinical sample of children of divorce for nearly four decades. Her conclusions match those of other researchers—children whose parents divorce are impacted throughout their lives in a variety of ways. The same could be said of children whose parents remained married and raised them in a caustic home environment.

Whenever a couple divorces (or separates for cohabiters) children experience changes in the stability of their lives at many levels. Some of these children have been through divorce more than once. When their parents divorce, children assume blame for it and believe that they should try to get their parents back together (Like Walt Disney’s The Parent Trap movie). In reality, the children typically don’t influence their parents’ choices to divorce directly and children are certainly part of the equation, but rarely the sole cause of divorce. On top of that divorce brings change which is stressful by its very nature. Children worry about being abandoned. They have had their core attachment to their parents violated.

They become disillusioned with authority as they try to balance the way things ought to be with the way things actually are. They become aware of ex-spouse tensions and realize that they themselves are the subject of some of these tensions.

Researchers agree that it is better for children to be forewarned of the coming divorce. Parents should make it clear to children that they are not the cause of divorce, that both parents still love them and will always be their parents. They should show them that even though divorce is difficult they can work together to get through it. Children should never be the messenger or go between or in any other way assume the burdens associated with the dissolved marriage. Table 4 presents some core guidelines for divorcing parents.

These are strategies that have been found to be present in strong divorced families. Much research is conducted on what’s working for these families. Unfortunately, many of these strategies can’t possibly work for ex-spouses who have much animosity toward each other. They are still harboring hurt feelings and can’t get past them right now-some never get pass them. Spouses who find themselves at the point of divorce would benefit, and the children would also benefit, from pre-divorce counseling. This is counseling to help them have a good divorce, not counseling to help them reconcile.

Table 4. Core Guidelines for Divorcing Parents.

- Respect each other, get along, and come to terms with the nuances of co-parenting.

- Set up and maintain predictable routines, especially with regard to the sharing of custody.

- Get professional help for children when needed.

- Ensure the safety and well-being of the children.

- Help children remember the good times before the marriage started to go sour.

- Ex-spouses should agree on discipline and be consistent in applying it.

- Encourage the children to have a strong relationship with ex-in-laws.

- Get your own professional help and avoid having the children be caregivers for the parents.

- Create new rituals.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2004 Detailed Tables-Number, Timing and Duration of Marriages and Divorces: 2004; Table 2 Percent Reaching Stated Anniversary, By Marriage Cohort and Sex, and Sex for first and Second Marriages, Retrieved 9 Sept 2009 from www.census.gov

- http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/01news/firstmarr.htm

- Glenn, N. D. (1991). The recent trend in marital success in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(2), 261-270.

- Lauer, R. (1986). ‘Til death do us part: How couples stay together; Google Lauer and Lauer and Kerr various years

- http://marriage.eharmony.com/

- see studies by Lawrence Ganong and Marilyn Coleman.

- Cherlin, A. J. (2008). Multiple partnerships and children’s wellbeing. Austrian Institute of Family Studies, 89, 33-36.