6

Donna Giuliani, RON HAMMOND AND PAUL CHENEY-UTAH VALLEY UNIVERSITY

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter you will be able to do the following.

- Differentiate between sex and gender.

- Compare and contrast the biological characteristics of males and females.

- Define gender socialization.

- Define gender roles.

- Differentiate between the “types” of husbands.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SEX AND GENDER?

By far, sex and gender has been one of the most socially significant social factors in the history of the world and the United States. Sex is one’s biological classification as male or female and is set into motion at the moment the sperm fertilizes the egg. Sex can be precisely defined at the genetic level with XX being female and XY being male. Believe it or not, there are very few sex differences based on biological factors. Even though male and female are said to be opposite sexes, biologically there is no opposite sex. Look at table 1 below to see sex differences. For the sake of argument, ignore the reproductive differences and you basically see taller, stronger, and faster males. The real difference is the reproductive body parts, their function, and corresponding hormones. The average U.S. woman has about two children in her lifetime. She also experiences a monthly period. Other than that and a few more related issues listed in Table 1, reproductive roles are a minor difference in the overall daily lives women, yet so very much importance has been placed on these differences throughout history.

We have much more in common than differences. In table 2 you see a vast list of similarities common to both men and women. Every major system of the human body functions in very similar ways to the point that health guidelines, disease prevention and maintenance, and even organ transplants are very similar and guided under a large umbrella of shared guidelines. True, there are medical specialists in treating men and women, but again the similarities outweigh the differences. Today you probably ate breakfast, took a shower, walked in the sunlight, sweated, slept, used the bathroom, was exposed to germs and pathogens, grew more hair and finger nails, exerted your muscles to the point that they became stronger, and felt and managed stress. So did every man and woman you know and in very similar ways.

Answer this question, which sex has Estrogen, Follicle Stimulating Hormone, Luteinizing Hormone, Prolactin, mammary glands, nipples, and even Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (at times)? Yes, you probably guessed correctly. Both males and females have all these hormones, plus many others including testosterone.

Table 1. Known Biological Sex Differences.1

Reproductive Traits

| Female | Male |

| Vagina | Penis |

| Uterus | Testicles |

| Ovaries | Scrotum |

| Breast development | Breast dormant |

| Cyclical hormones | Other |

| Shorter | Taller |

| Less Aggressive | More aggressive |

| Runs a bit slower | Rus a bit faster |

| Less upper body strength | More upper body strength |

| Life span about 7 years longer in developed countries | Life span about 3 years shorter worldwide |

Table 2. Known Biological Sex Similarities.

|

Digestive System |

|

Respiratory System |

|

Circulatory System |

|

Lymphatic System |

|

Urinary System |

|

Musculoskeletal System |

|

Nervous System |

|

Endocrine System |

|

Sensory System-5 |

|

Immune System |

|

Integumentary System- Skin, Hair, and Nails |

|

Excretory System |

Not only are males and females very similar, but science has shown that we truly are more female than male in biological terms. So, why the big debate of the battle of the sexes? Perhaps it’s because of the impact of gender (the cultural definition of what it means to be a man or a woman). Gender is culturally-based and varies in a thousand subtle ways across the many diverse cultures of the world. Gender has been shaped by political, religious, philosophical, language, tradition and other cultural forces for many years. Gender roles are also socially and culturally-based and are that set of norms that are attached to a specific gender. Gender identity is our personal internal sense of our own maleness or femaleness. Every society has a slightly different view of what it means to be male/masculine and female/feminine. Masculine traits are those we associate with being male, such as aggressiveness, directness, independence, objectiveness, and leadership.

Feminine traits are being talkative, submissive, nurturing, emotional, and illogical. Androgyny is when a person shares both masculine and feminine traits. They fit their behaviour to the situation; so an androgynous person might cry at a wedding or funeral, but can also change the tire on a car.

To this day, in most countries of the world women are still oppressed and denied access to opportunities more than men and boys. This can be seen through many diverse historical documents. When reading these documents, the most common theme of how women were historically oppressed in the world’s societies is the omission of women as being legally, biologically, economically, and even spiritually on par with men. The second most common theme is the assumption that women were somehow broken versions of men.2

Biology has disproven the belief that women are broken versions of men. In fact, the 23rd chromosome looks like XX in females and XY in males and the Y looks more like an X with a missing leg than a Y. Ironically, science has shown that males are broken or variant versions of females and the more X traits males have the better their health and longevity.

DEBUNKING MYTHS ABOUT WOMEN

In Table 1 you saw how females carry the lion’s share of the biological reproduction of the human race. Since history assumed that women were impaired because of their reproductive roles (men were not), societies have defined much of these reproductive traits as hindrances to activities.

Professor Hammond found an old home health guide at an antique store in Ohio. He was fascinated that in 1898 the country’s best physicians had very inaccurate information and knowledge about the human body and how it worked.3 Interestingly, pregnancy was considered “normal” within most circumstances while menstruation was seen as a type of disease process that had to be treated (back then and today most physicians were men). On pages 892-909 it refers to menstrual problems as being “unnatural” and that they are normal only if “painless” and thus the patient should be treated rather than the “disease.” Indeed from a male scientific perspective in 1898, females and their natural reproductive cycles were problematic.

But, to the author, females were more fragile and vulnerable and should be treated more carefully than males especially during puberty. Patton states, “The fact is that the girl has a much greater physical and a more intense mental development to accomplish than the boy…” As for public education, he states that “The boy can do it; the girl can—sometimes…” He attributes most of the female sexual and reproductive problems to public school which is a by-product of “women’s rights, so called.”

He’d probably be stunned to see modern medicine’s discoveries today. In our day, women are not defined as being inferior in comparison to men. But, in 1898, a physician (source of authority and scientific knowledge) had no reservations about stating the cultural norm in print, that women were considered broken in contrast to men.

Gender Socialization is the shaping of individual behavior and perceptions in such a way that the individual conforms to the socially prescribed expectations for males and females. One has to wonder what might have been different if all women were born into societies that valued their uniqueness and similarities in comparison to men. How much further might civilizations have progressed? It is wise to avoid the exclusion of any category of people—based on biological or other traits—from full participation in the development of knowledge and progress in society. In the history of the world, such wisdom has been ignored far too often.

GENDER ROLES AS A SOCIAL FORCE

One can better understand the historical oppression of women by considering three social factors throughout the world’s history religion, tradition, and labor-based economic supply and demand. In almost all of the world’s major religions (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and many others) very clear distinctions have been made about gender roles are socialized expectations of what is normal, desirable, acceptable, and conforming for males and females in specific jobs or positions in groups and organizations over the life course. These gender roles have very specific meanings for the daily lives and activities of males and females who live under the religious cultures in nations throughout history and even in our day. The Book of Leviticus in the JudeaoChristian Old Testament has many biological rituals based specifically on women’s hygiene. A close friend of mine performed her Master’s thesis in Ancient Near East Studies on the reproductive hygiene rituals described in the book of Leviticus.4 In brief, she found no modern-day scientific support for these religious rituals on female’s health nor on their reproduction. Her conclusion was that these were religious codes of conduct, not biologically-based scientifically beneficial codes.

Many ancient writings in religions refer to the flaws of females, their reproductive disadvantages, their temperament, and the rules that should govern them in the religious community. Many current religious doctrines have transformed as society’s values of gender equality have emerged. The point is that throughout history, religions were a dominant social force in many nations and the religious doctrines, like the cultural values, often placed women in a subjugated role to men and a number of different levels.

The second social force is tradition. Traditions can be and have been very harsh toward women. Table 3 shows a scale of the outcomes of oppression toward women that have and currently do exist somewhere in the world. Even though the average woman out lives the average man by three years worldwide and seven years in developed countries, there are still a few countries where cultural and social oppression literally translates into shorter life expectancies for women (Niger, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia have lower death rates for women while Kenya, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, and Micronesia have a tie between men and women’s life expectancy—this even though in developing nations the average woman outlives the average man by three years.).

Some cultural traditions are so harsh that females are biologically trumped by males by withholding nutrition, abandoning wife and daughters, abuse, neglect, violence, refugee status, diseases, and complications of childbirth unsupported by the government. If you study this online looking at the Population Reference Bureau’s many links and reports, you will find a worldwide concerted effort to persuade government, religious, and cultural leaders to shift their focus and efforts to nurture and protect females.5 Progress has already been made to some degree, but much change is still warranted because life, health and well-being are at stake for billions of women worldwide.

Table 3. Outcomes of 10 Forms of Oppression of Women.6

|

Death from cultural and social oppression (Various Countries) |

|

Sexual and other forms of slavery (Western Africa and Thailand) |

|

Maternal deaths (Sub-Sahara Africa and developing nations) |

|

Female Genital Mutilation (Mid- Africa about 120 million victims) |

|

Rape and sexual abuse (South Africa and United States are worst countries) |

|

Wage disparity (worldwide) |

|

No/low education for females (various degrees in most countries of the world) |

|

Denial of access to jobs and careers (many developing nations) |

|

Mandatory covering of females’ bodies head to toe (Traditional countries,Muslim) |

|

Public demeaning of women (still practiced, public and private) |

One of the most repugnant traditions in our world has been and still is the sale of children and women into sexual and other forms of slavery. Countless civilizations that are still influential in our modern thought and tradition have sold girls and women the same way one might sell a horse or cow. It’s estimated by a variety of organizations and sources that about one million women are currently forced into the sex slavery industry (boys are also sold and bought into slavery). India, Western Africa, and Thailand are some of the most notorious regions for this atrocity.7 Governments fail at two levels in the sexual slavery trade First, they allow it to occur as in the case of Thailand where it’s a major draw of male tourists and Second, they fail to police sexual slavery which is criminal and often connected to organized crime. The consequences to these girls and women are harsh at every level of human existence and are often connected to the spread of HIV and other communicable diseases.

Although pregnancy is not a disease it carries with it many health risks when governments fail to provide resources to expecting mothers before, during, and after delivery of their baby. Maternal Death is the death of a pregnant woman resulting from pregnancy, delivery, or recovery complications. Maternal deaths number in the hundreds of thousands and are estimated by the United Nations to be around ½ million per year worldwide.8 Typically very little medical attention is required to prevent infection, mediate complications, and assist in complications to mothers. To answer this problem one must approach it at the larger social level with government, health care systems, economy, family, and other institutional efforts. The Population Reference Bureau puts a woman’s risk of dying from maternal causes at 1 in 92 worldwide with it being as low as 1 in 6,000 in developed countries and as high as 1 in 22 for the least developed regions of the world.9 The PRB reports “little improvement in maternal Mortality in developing countries.

Female Genital Mutilation is the traditional cutting, circumcision, and removal of most or all external genitalia of women for the end result of closing off some or part of the vagina until such time that the woman is married and cut open. In some traditions, there are religious underpinnings. In others, there are customs and rituals that have been passed down. In no way does the main body of any world religion condone or mandate this practice—many countries where this takes place are predominantly Muslim—yet local traditions have corrupted the purer form of the religion and its beliefs and female genital mutilation predates Islam.11 An analogy can be drawn from the Taliban, which was extreme in comparison to most Muslims worldwide and which literally practiced homicide toward its females to enforce conformity. It should also be explained that there are no medical therapeutic benefits from female genital mutilation. Quite the contrary, there are many adverse medical consequences that result from it including pain, difficulty in childbirth, illness, and even death.

Many human rights groups, the United Nations, scientists, advocates, the United States, the World Health Organization, and other organizations have made aggressive efforts to influence the cessation of this practice worldwide. But, progress has come very slowly. Part of the problem is that women often perform the ritual and carry on the tradition as it was perpetrated upon them. In other words, many cases have women preparing the next generation for it and at times performing it on them.

The mandatory covering of females’ bodies head to toe has been opposed by some and applauded by others. Christians, Hindus, and many other religious groups have the practice of covering or veiling in their histories. As fundamentalist Muslim nations and cultures have returned to their much more traditional way of life, hijab which is the Arabic word that means to cover or veil has become more common. Often hijab means modest and private in the day-to-day interpretations of the practice. For some countries it is a personal choice, while for others it becomes a crime not to comply. The former Taliban, punished such a crime with death (they also punished formal schooling of females and the use of makeup by death).

Many women’s rights groups have brought public attention to this trend, not so much because the mandated covering of females is that oppressive, but because the veiling and covering is symbolic of the religious, traditional, and labor-forced patterns of oppression that have caused so many problems for women and continue to do so today.

Professor Ron Hammond interviewed a retired OBGYN nurse who served as a training nurse for a mission in Saudi Arabia on a volunteer basis. She taught other local nurses from her 30 years of experience. Each and every day she was guarded by machine gun toting security forces everywhere she went. She was asked to cover and veil and did so. Ron asked her how she felt about that, given that her U.S. culture was so relaxed on this issue.

“I wanted to teach those women and knew that they would benefit from my experience. I just had to do what I was told by the authorities,” she said.

“What would have happened if you had tried to leave the compound without your veil?” Ron asked.

“I suspect, I would have been arrested and shot.” She chuckles. “Not shot, perhaps, but if I did not comply, my training efforts would have been stopped and I would have been sent home.”

“So, you complied because of your desire to train the nurses?” “That and the mothers and babies.” She answered.12

The public demeaning of women has been acceptable throughout various cultures because publicly demeaning members of society who are privately devalued and or considered flawed fits the reality of most day-to-day interactions. Misogyny is the physical or verbal abuse and mistreatment of women. Verbal misogyny is unacceptable in public in most Western Nations today. With the ever present technology found in cell phones, video cameras, and security devices a person’s private and public misogynistic language could easily be recorded and posted for millions to see on any number of websites.

Perhaps, this fear of being found out as a woman-hater is not the ideal motivation for creating cultural values of respect and even admiration of women and men. As was mentioned above, most of the world historical leaders assumed that women were not as valuable as men and it has been a few decades since changes have begun. Yet, an even more sinister assumption has and does persist today that women were the totality of their reproductive role, or Sex=Gender (Biology=Culture). If this were true then women would ultimately just be breeders of the species, rather than valued human beings they are throughout the world today.

RAPE

Rape is not the same as sex. Rape is violence, motivated by men with power, anger, selfish, and sadistic issues. Rape is dangerous and destructive and more likely to happen in the United States than in most other countries of the world. There are 195 countries in the world today. The U.S. typically is among the worst five percent in terms of rape (yes, that means 95% of the world’s countries are safer for women than the U.S.). Consecutive studies performed by the United Nations Surveys on crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems confirm that South Africa is the most dangerous, crime-ridden nation on the planet in all crimes including rape.13

The world’s histories with very few exceptions have recorded the pattern of sexually abusing boys, girls, and women. Slavery, conquest of war, kidnapping, assault, and other circumstances are the context of these violent practices. Online there is a Website at www.rainn.org which is a tremendous resources for knowledge and information especially about rape, assault, incest and issues relating to the United States. The United Nations reported that, “Women aged 15-44 are more at risk from rape and domestic violence than from cancer, motor accidents, war and malaria,” according to World Bank data.14 The UN calls for a criminal Justice System response and for increased prioritization and awareness. Anything might help since almost every country of the world is struggling to prevent sexual violence and rape against its females.

OPPORTUNITIES

Wage disparity between males and females is both traditional and labor-based economic supply and demand. Statistics show past and current discrepancies in lower pay for women. Diane White made a 1997 presentation to the United Nations General Assembly stated that “Today the wage disparity gap cost American women $250,000 over the course of their lives.”15 Indeed evidence supports her claim that women are paid less in comparison to men and their cumulated losses add up to staggering figures. The U.S. Census Bureau reported in 2008 that U.S. women earn 77 cents for every U.S. man’s $1.16 They also reported that in some places like Washington DC and in certain fields (like computers and mathematical) women earn as much as 98 cents per a man’s $1. At the worldwide level “As employees, women are still seeking equal pay with men. Closing the gap between women’s and men’s pay continues to be a major challenge in most parts of the world.”17 The report also discussed the fact that about 60 countries have begun to keep statistics on informal (unpaid) work by women. Needless to say even though measuring paid and unpaid work of women is not as accurate as needed for world considerations, “Women contribute to development not only through remunerated work but also through a great deal of unremunerated work.”18

Why the lower wages for women? The traditional definition of the reproductive roles of women as being broken, diseased, or flawed is part of the answer of wage disparity. The idea that reproductive roles interfere with the continuity of the workplace and the idea that women cannot be depended on plays heavily into the maltreatment of women. The argument can be made that traditional and economic factors have lead to the existing patterns of paying women less for their same education, experience, and efforts compared to men.

Efforts to provide formal education to females worldwide have escalated over the last few decades. The 2002 Kids Count International Data Sheet estimated rates as low as 11 percent of females in primary school in Somalia.19 A 1993 World Bank report made it very clear that females throughout the world were being neglected in receiving their formal educations when compared to males.20 In 1998 another example is found in efforts specific to Africa via the Forum of African Women Educationalists which focuses on governmental policies and practices for female education across the continent.21 Literally hundreds of studies have since focused on other regions around and below the equator where education levels for females are much lower.

In 1999 it was reported by UNICEF that 1 billion people would never learn to read as children with 130 million school aged children (73 million girls) without access to basic education.22 Another UNICEF 2008 report clearly identifies the importance of educating girls who grow up to be mothers because of the tremendous odds that those educated mothers will ensure that their children are also formally educated.23 In its statistical tables it shows that Somalia is now up to 22 percent for boys and girls in primary schools, yet in most countries females are still less likely to be educated.24 The main point from UNICEF and many other formal reports is that higher formal education for females is associated with life, health, protection from crime and sexual exploitation, and countless other benefits, especially to females in the poorer regions of the world. In the United States most females and males attend some form of formal education. After high school, many go to college.

Even though the U.S. numbers of 18 to 24 year old men are higher than women,25 women are more likely to attend college based on percentages (57%).26

A projection from the National Center for Education Statistics projects a continuing trend up and through the year 2016 where about 58% of U.S. college students will be female.27 By 2016 about 60% of graduated students will be females.28 These numbers reflect a strong and concerted push toward equality of opportunity for females in formal education that does date back over a century. The challenge is to avoid defining progress for U.S. females in public and private education as having been made at the expense of males. That’s much too simplistic.

They also reflect a change in the culture of breadwinning and the adult roles of males. Males and/or females who don’t pursue a college degree will make less money than those who did. To make sense of this trend, many males have been identified as having a prolonged adolescence (even into their 30’s); video game playing mentality; and a live with your parents indefinitely strategy until their shot at the labor force has passed them by. Others have pointed out the higher rates of learning disabilities in K-12, the relatively low percentage of K-5 teachers who are males, and the higher rate of male dropouts. Still others blame attention deficit and hyperactivity as part of the problem. Here is a truism about education in the U.S.

Higher education=higher pay=higher social prestige=higher income=higher quality of life.

Many countries of the world have neutralized the traditional, religious, and labor-force based biases against women and have moved to a merit-based system. Even in the U.S., there have been “men’s wages, then women and children’s wages (1/10th to 12/3rd of a man’s). In a sense, any hard working, talented person can pursue and obtain a high-end job, including women.

Communism broke some of these barriers early on in the 20th century, but the relatively low wages afforded those pursuing these careers somewhat offset the advances women could have made. In the U.S. progress has come more slowly. Physicians are some of the brightest and best paid specialists in the world. Salaries tend to begin in the $100,000 range and can easily reach $500,000 depending on the specialty.29 Prior to 1970 most physicians were white and male, but things are slowly changing. Table 4 shows the trends between 1970 and 2006.

|

Year |

Male |

Female |

|

1970 |

92.40 |

7.60 |

|

1980 |

88.40 |

11.60 |

|

1990 |

83.10 |

16.90 |

|

2000 |

76.30 |

24.00 |

|

2002 |

74.80 |

25.20 |

|

2003 |

74.20 |

25.80 |

|

2006 |

72.20 |

27.80 |

Table 4. Percentage of Physicians who are Male and Female.30

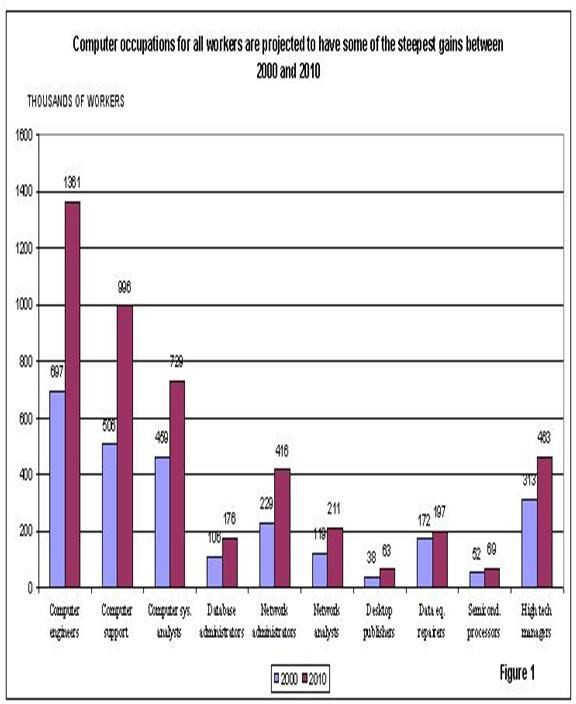

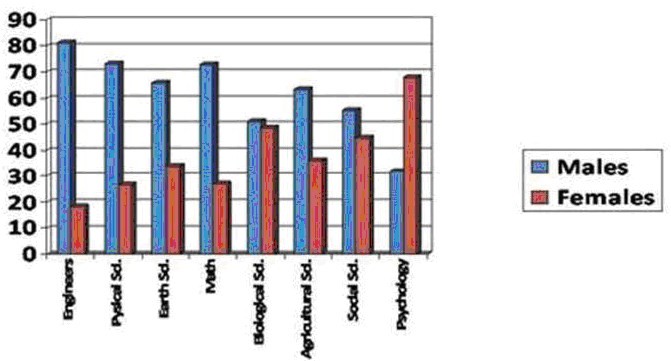

The upward trend shows a concerted effort to provide equal opportunity for females and males. Engineers have also seen a concerted effort to facilitate females into the profession. The Society of Women Engineers is a nonprofit organization which helps support and recognize women as engineers.31 Figure 1 shows how computer-based careers are seeing striking gains in some areas for women who will be hired competitively based on merit. The same cannot be said for doctoral level employment in the more prestigious fields. Figure 2 shows 2005 estimates from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The first six fields are the highest paying fields to work in while social and psychological sciences are among the least paying. Women clearly dominate Psychology and nearly tie in social sciences and biology. True, at the doctoral level pay is higher than at the masters and bachelors levels, but the difference in engineering and psychology is remarkable at every level of education.32

RESEARCH ON GENDER

An early pioneer is an anthropologist named, Margaret Mead (1901-1978). Dr. Mead earned her Ph.D. under the direction of some of the best anthropologists of her day. But, she was a woman in a mostly male-dominated academic field. She is an example of someone who successfully challenged the sexist and misogynistic notions established in academics at the time.

Mead’s work entitled, Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (1935) became a major seminal work in the women’s liberation movement and thereby in the redefinition of women in many Western Societies. Her observations of gender in three tribes Arapesh, Mundugamor, and Tchambuli created a national discussion which lead many to reconsider the established Sex=Gender assumption. In these tribes she found the following. In the Arapesh both men and women displayed what we typically call feminine traits sensitivity, cooperation, and low levels of aggression. In the Mundugamor both men and women were insensitive, uncooperative, and very aggressive. These were typical masculine traits at the time. In contrast to most societies the Tchambuli women were aggressive, rational, and capable and were also socially dominant while the men were passive, assuming artistic and leisure roles.

Figure 1. Women in High Tech Jobs.33

Figure 2. United States Doctorates Conferred By Characteristics of Recipients, 2005.34

Why then, Mead argued, if our reproductive roles determined our cultural and social opportunities were the gender definitions varied and unique among less civilized peoples? Were we not less civilized ourselves at one point in history and have we not progressed on a similar path the tribal people take? Could it be that tradition (culture) was the stronger social force rather than biology? Mead’s work and her public influence helped to establish the belief that biology is only a part of the Sex and Gender question (albeit an important part). Mead established that Sex≠Gender. But, even with the harshest criticism launched against her works, her critics supported and even inadvertently reinforced the idea that biology shapes but cultures are more salient in how women and men are treated by those with power.

Misogyny is easier to perpetrate if one assumes the weakness, biological frailty, and perhaps even diminished capacity that women were claimed to have had. Andrew Clay Silverstein (AKA Andrew Dice Clay) was a nationally successful comedian who also played in a movie and TV show (although he recently appeared on Celebrity Apprentice). His career ended abruptly because of his harsh sexist themes which were being performed in an age of clarity and understanding about gender values. Mr. Clay failed to recognize the social change which surrounded him. We often overlook the change and the continuing problems ourselves.

Professional and volunteer organizations have made concerted efforts to raise awareness of the English language and its demeaning language toward females. English as a derivative of German has many linguistic biases against women, non-whites, poor, and non-royalty. Raising awareness and discussing the assumptions within English or any other language has been part of the social transformation toward cultural and biological fairness and equality. If we understand how the words we use influence the culture we live in and how the value of that culture influence the way we treat one another, then we begin to see the importance of language on the quality of life.

The quality of life for women is of importance at many different levels in the world. As you’ve read through this chapter, you’ve probably noticed that much is yet to be accomplished worldwide. The United States has seen much progress. But, other nations continually rank the “world’s best nation for women.” Many European countries far outrank the U.S. for quality of Women’s lives. In Fact, in 2008 the U.S. ranked number 27th.35

The Global Gender Gap Index was developed to measure the quality of life for women between countries. It measures the gap between males and females in objective statistics that focus on equality. There are four pillars in the index economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, political empowerment, and health and survival using 14 indicators from each countries national statistics. From 1998-2006, there was a reported net improvement for all countries.36

When one considers the day-to-day lives of women in these national statistics, and perhaps more importantly in their personal lives, the concept of what women do as their contribution to the function of society becomes important. Instrumental tasks are goal directed activities which link the family to the surrounding society, geared toward obtaining resources. This includes economic work, breadwinning, and other resource-based efforts. Expressive tasks are tasks that pertain to the creation and maintenance of a set of positive, supportive, emotional relationships within the family unit. This includes relationships, nurturing, and social connections needed in the family and society. Today, women do both and typically do them well.

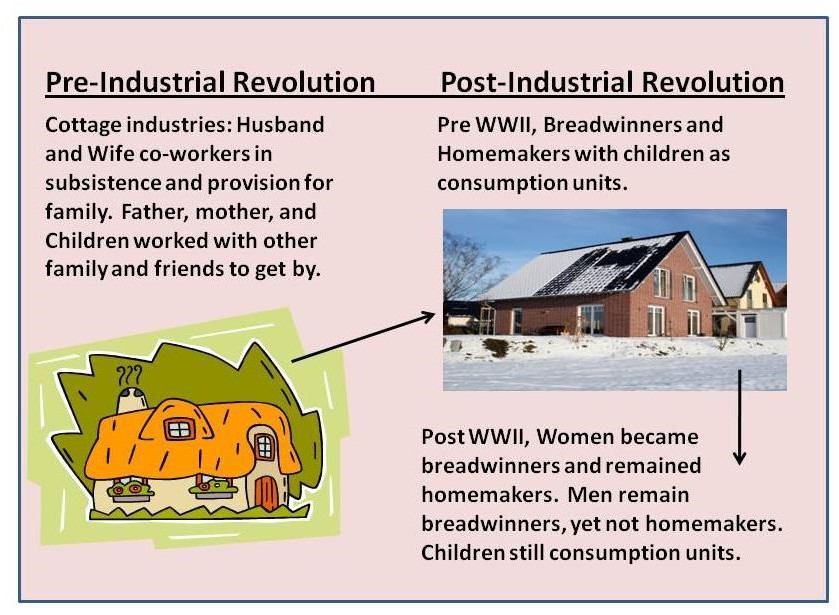

Prior to the Industrial Revolution both males and females combined their local economic efforts in homemaking. Most of these efforts were cottage industry-type where families used their children’s labor to make products they needed from soap, thread, fabric, butter, and many other products.

When the factory model of production emerged in Western civilizations, the breadwinner and homemaker became more distinct. Breadwinner is a parent or spouse who earns wages outside of the home and uses them to support the family. Homemaker is typically a woman who occupies her life with mothering, housekeeping, and being a wife while depending heavily on the breadwinner.

FEMINISM

Many thanks to Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken for a comprehensive OER source text.

Summary of The Women’s Movement Toward Equality

What equality means changes depending on societal structures. In the 1920s, the vote for white women and financial independence from husbands seemed a daunting goal. Then in the 1960s, the right to keep those Rosie the Riveter jobs and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 that finally gave Black women access to the voting booth was a significant fight. Then again, following the 1980s recession and color-blind racism, a third wave attempted to be more inclusive and talked openly about not centering white and educated women’s experiences over often marginalized women. This fourth wave is still under discussion, but combating domestic violence, sexual harassment, and other forms of misogyny are at the forefront. This fourth wave uses social media as a mobilizing tool and is more inclusive of LGBTQIA folx.

- First wave crested in the 1920s, Right to Vote

- Second wave crested in the 1960s, Right to Work

- Third wave crested in the 1980s and 90s, Equal Pay for Equal Work

- Fourth wave started a bit before 2012, Holding the Patriarchy Accountable

Expanded version: Feminist Movements

Feminist historian Elsa Barkley Brown reminds us that social movements and identities are not separate from each other, as we often imagine they are in contemporary society. There is some overlap between different “waves” of the 100+ year feminist movement in the United States, as there are evolving goals and degrees of societal resistance to women’s equality. The central feminist movement’s focus of equality shifts as some goals are achieved, modified, shifted, postponed, or discarded. It is also important to note that the dominant power structure of the time defines whose goals are promoted, achieved, and who benefits the most from the effort.

The feminist movement has some notable figures and some significant accomplishments, but it is important to remember that this history of notables hides that most of the work and sacrifice was made by the anonymous community of organizers behind the headlines. And that many of the people, particularly women of color, did not reap the rewards of their labor in the way that white women did.

19th Century Feminist Movements

What has come to be called the first wave of the feminist movement began in the mid 19th century and lasted until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave white women the right to vote. White middle-class first wave feminists in the 19th century to early 20th century, such as suffragist leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, primarily focused on women’s suffrage (the right to vote), gaining access to education and employment, and striking down coverture – laws declaring that women’s legal rights and obligations are under their husband’s authority. These goals are famously enshrined in the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments, which is the resulting document of the first women’s rights convention in the United States in 1848.

Demanding women’s enfranchisement, the abolition of coverture, and access to employment and education were quite radical demands at the time. These demands confronted the ideology of the cult of true womanhood, summarized in four key tenets—piety, purity, submission and domesticity—which held that white women were rightfully and naturally located in the private sphere of the household and not fit for public, political participation or labor in the waged economy. This first wave of the feminist movement was very much driven by the goals of white and affluent women. It is important to note that the ideological target of this movement, the cult of true womanhood, by definition, excludes Black and working-class women because they labored outside of the home.

The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 provided a test for the argument that granting women the right to vote would give them unfettered access to institutions and equality with men. History paints the passage of the 19th Amendment as the moment women secured the right to vote in the United States, but most Black women, many of whom had worked exhaustively for the rights of women to vote, did not achieve the vote until nearly five decades later. This is because Jim Crow laws in states across the country, and the unchecked violence of the Ku Klux Klan, prevented Black women and men from access to voting, education, employment, and public facilities. While equal rights existed in the abstract realm of the law under the 13th and 19th amendments, the on-the-ground reality of continued racial and gender inequality was quite different.

Early to Late 20th Century Feminist Movements

The second wave of the feminist movement does not have a clear cut start because the work from the 1920s never ended, it just evolved. But there is definitely a shift in focus with World War II, and the decade following World War II generally defines our second wave. Of course there is significant intersection between second wave feminism and the Civil Rights Movement. Just as the first wave prioritized white, middle-class, women’s goals while it gladly accepted the labor of Black women and poor women, the second wave did too.

While millions of poor women and BIPOC women were already working in the United States at the beginning of World War II, labor shortages during World War II allowed millions of women to move into higher-paying factory jobs that had previously been occupied by men. And then when soldiers returned to the states following the end of the war, they came home to women who had been working in jobs, earning decent money, controlling their own homes, and making the decisions about their own spending.

The second wave feminist movement focused generally on fighting patriarchal structures of power, and specifically on combating occupational sex segregation in employment and fighting for reproductive rights for women. However, this was not the only source of second wave feminism, and white women were not the only women spearheading feminist movements. As historian Becky Thompson (2002) argues, in the mid and late 1960s, Latina women, African American women, and Asian American women were developing multiracial feminist organizations that would become important players within the U.S. second wave feminist movement.

In many ways, the second wave feminist movement was influenced and facilitated by the activist tools provided by the civil rights movement. Drawing on the stories of women who participated in the civil rights movement, historians Ellen Debois and Lynn Dumenil (2005) argue that women’s participation in the civil rights movement allowed them to challenge gender norms that held that women belonged in the private sphere, and not in politics or activism. Not only did many women who were involved in the civil rights movement become activists in the second wave feminist movement, they also employed tactics that the civil rights movement had used, including marches and non-violent direct action. Additionally, the Civil Rights Act of 1964—a major legal victory for the civil rights movement—not only prohibited employment discrimination based on race, but Title VII of the Act also prohibited sex discrimination. When the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)—the federal agency created to enforce Title VII—largely ignored women’s complaints of employment discrimination, 15 women and one man organized to form the National Organization of Women (NOW), which was modeled after the NAACP. NOW focused its attention and organizing on passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), fighting sex discrimination in education, and defending Roe v. Wade—the Supreme Court decision of 1973 that struck down state laws that prohibited abortion within the first three months of pregnancy.

Third Wave Feminism

Third wave feminism is, in many ways, a hybrid creature. It is influenced by second wave feminism, Black feminisms, transnational feminisms, Global South feminisms, and queer feminism. This hybridity of third wave activism comes directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries who have grown up in a world that supposedly does not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women have been guaranteed by law in most countries. The gap between law and reality—between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience—however, reveals the necessity of both old and new forms of activism.

In the 1980s and 1990s, third wave feminists took up activism in a number of forms, ultimately resulting in the 1994 hotly debated and legally contested Violence Against Women Act. Also significant is the 1980s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which began organizing to press an unwilling US government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS. In the latter part of the 1980s, a more radical subset of individuals began to articulate a queer politics, explicitly reclaiming a derogatory term often used against gay men and lesbians, and distancing themselves from the gay and lesbian rights movement, which they felt mainly reflected the interests of white, middle-class gay men and lesbians.

In this vein, Lisa Duggan (2002) coined the term homonormativity, which describes the normalization and de-politicization of gay men and lesbians through their assimilation into capitalist economic systems and domesticity—individuals who were previously constructed as “other.” These individuals thus gained entrance into social life at the expense and continued marginalization of people who were non-white, disabled, trans, single or non-monogamous, middle-class, or non-western. Critiques of homonormativity were also critiques of gay identity politics, which left out concerns of many gay individuals who were marginalized within gay groups. There is a prominent author of children’s wizardry books who is very publicly third wave feminist and caustically transphobic. Because this is a rather common theme for third wave, a fourth distinction is brewing.

Defining the Fourth Wave -starting somewhere around 2012

There are plenty of people who are not convinced we are in a fourth wave of the feminist movement. Yet the conversations of today are markedly different than the pantsuits and political organizing of the 90s. Within the last decade the volume of protest and legal action has intensified, and the movement is getting results (#MeToo, #YesAllWomen, etc.). This generation’s young people are more politically active, more inclusive, and are more vocal in their advocacy. While intersectionality was very much a part of third wave feminism, fourth wave feminism embraces gender fluidity and the LGBTQIA community, and mixes racial justice, environmental justice, economic justice, etc. into activism. This wave uses social media as a tool for propelling social change in a way that was inconceivable in the 1990s.

The emphasis on coalitional politics and making connections between several movements is another crucial contribution of feminist activism and scholarship. In the 21st century, feminist movements confront an array of structures of power: global capitalism, the prison system, war, racism, ableism, heterosexism, and transphobia, among others. What kind of world do we wish to create and live in? What alliances and coalitions will be necessary to challenge these structures of power? How do feminists, queers, people of color, trans people, disabled people, and working-class people go about challenging these structures of power? These are among some of the questions that feminist activists are grappling with now, and their actions point toward a deepening commitment to an intersectional politics of social justice and praxis.

WHAT ABOUT MEN?

In the past two decades a social movement referred to as The Men’s Movement has emerged. The Men’s Movement is a broad effort across societies and the world to improve the quality of life and family-related rights of men. Since the Industrial Revolution, men have been emotionally exiled from their families and close relationships. They have become the human piece of the factory machinery (or computer technology in our day) that forced them to disconnect from their most intimate relationships and to become money-acquisition units rather than emotionally powerful pillars of their families.

Many in this line of thought attribute higher suicide rates, death rates, accident rates, substance abuse problems, and other challenges in the lives of modern men directly to the broad social process of post-industrial breadwinning. Not only did the Industrial Revolution’s changes hurt men, but the current masculine role is viewed by many as being oppressive to men, women, and children. Today a man is more likely to kill or be killed, to abuse, and to oppress others. Some of the issues of concern for those in the Men’s Movement include life and health challenges, emotional isolation, post-divorce/separation father’s rights, false sexual or physical abuse allegations, early education challenges for boys, declining college attendance, protection from domestic abuse, manhating or bashing, lack of support for fatherhood, and paternal rights and abortion.

The list of concerns displays the quality of life issues mixed in with specific legal and civil rights concerns. Men’s Movement sympathizers would most likely promote or support equality of rights for men and women. They are aware of the Male supremacy model, where males erroneously believe that men are superior in all aspects of life and that should excel in everything they do. They also concern themselves with the Sexual objectification of women, where men learn to view women as objects of sexual consumption rather than as a whole person. Male bashing is the verbal abuse and use of pejorative and derogatory language about men.

These and other concerns are not being aggressively supported throughout the world as are the women’s rights and suffrage efforts discussed above. Most of the Men’s Movement efforts are in Western Societies, India, and a handful of others.

Figure 3 shows the transition in family gender roles over the course of the Industrial Revolution through to Post World War II. Families in Pre-Industrial Europe and the U.S. were subsistence based; meaning they spent much of their daily lives working to prepare food and other goods on a year-round basis. Men, women, children, and other family and friends succeeded because they all contributed to the collective good of the family economy.

Figure 3. The Western Family Pre- Post, and Post-WWII, especially for the United States.

The Industrial Revolution created the roles of breadwinners and homemakers. After the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, women continued their subsistence work and remained homemakers while men continued in their breadwinning roles. After World War II, there was a social structural change where women began assuming the breadwinner role and became more and more common among the ranks of paid employees, especially beginning in 1960s-1980s. They had managed to remain homemakers, but men had not moved into the homemaking role to the same degree that women had moved into the breadwinning role. This creates a strong level of burden and expectation for U.S. women who find themselves continuing to work outside the home for pay and inside the home for their informal domestic roles.

Men often find a closer bond to their wife, children, and other family members when they engage in domestic homemaking roles. Mundane family work is the activity that facilitates ongoing attachments and bonds among those who participate in it together.

Many couples today already share homemaking roles, just out of practical and functional need. They often find the co-homemaking/breadwinning role to be defined in a few typical styles. First, is the tourist husband style. The tourist husband is a visitor to the homemaking role who contributes the occasional assistance to his wife as a courtesy—much like a tourist might offer occasional assistance to their host. He often believes himself to be very generous since it is hers and not his role. Second, is the assistant homemaker where the husband looks to his wife for direction and for instruction on how to “help” her out in her homemaking role. Like one of the children, housework and homemaking task are the mother/wife’s job and he helps if called upon.

Finally, there is the co-homemaker husband who never “helps” his wife with homemaking task, but assumes that she and he equally share their breadwinning and homemaking responsibilities. The Cohomemaker husband is most likely to bond with his children, understand the daily joys and sorrows of all his individual family members, and feel a strong connection to his home and family (something Men’s Movement advocates lament having lost).

References:

Barkley Brown, E. 1997. “What has happened here’: The Politics of Difference in Women’s History and Feminist Politics,” Pp. 272-287 in The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory, edited by Linda Nocholson. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cott, N. 2000. Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Davis, Angela. 1983. Women, Race, Class. New York, NY: Random House.

— 1981. “Working Women, Black Women and the History of the Suffrage Movement,” Pp. 73-78 in A Transdisciplinary Introduction to Women’s Studies, edited by Avakian, A. and A. Deschamps. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Debois, E. and L. Dumenil. 2005. Through Women’s Eyes: An American History With Documents. St. Martin Press.

Duggan, Lisa. 2002. “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism.” Pp. 175-194 in Materializing Democracy, edited by R. Castronovo and D. Nelson. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Durso, L.E., & Gates, G.J. 2012. “Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth who are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless.” Los Angeles: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund.

Hayden, C. and M. King. 1965. “Sex and Caste: A Kind of Memo.” Available at: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/sexcaste.html. Accessed 3 May, 2011.

Hernandez, D. and B. Rehman. 2002. Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism. New York, NY: Seal Press.

Heywood, L. and J. Drake. 1997. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

hooks, bell. 1984. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, second ed. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2016. “Compilation of U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey. Historical Income Tables: Table P-38. Full-Time, Year Round Workers by Median Earnings and Sex: 1987 to 2015.” Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/incomepoverty/historical-income-people.html. Accessed 8 June, 2017.

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Ana , M. 2016. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Kang, Miliann, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken. Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. University of Amherst, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. http://www.oercommons.org/courses/introduction-to-women-gender-sexuality-studies/view

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1991. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses”. In Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, ed. Mohanty, Chandra Talpade, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Odo, Franklin. 2017. “How a Segregated Regiment of Japanese Americans Became One of WWII’s Most Decorated.” New America. Available at: https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/edition-150/how-segregated-regiment-japanese-americans-became-one-wwiis-most-decorated/. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Painter, Nell. 1996. Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton.

Puar, Jasbir. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rubin, G. 1984. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” in Carole Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sommers, Christina Hoff. 1994. Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women. New York: Doubleday.

Takaki, Ronald. 2001. Double Victory: A Multicultural History of America in World War II. Back Bay Books.

Thompson, Becky. 2002. “Multiracial Feminism: Recasting the Chronology of Second Wave Feminism,” Feminist Studies 28(2): 337-360.

Truth, Sojourner. 1851. “Ain’t I a Woman?” Available at: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/sojtruth-woman.html. Accessed 3 May, 2011.

Wells, Ida B. 1893. “Lynch Law.” Available at: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/wellslynchlaw.html. Accesssed 15 May, 2017.

Zinn, H. 2003. A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Previous: Third Wave and Queer Feminist Movements

See www.prb.org World Population Data Sheet 2008.

Google: Aristotle’s The Generation of Animals, Sigmund Freud’s Penis Envy, or John Grey’s Mars and Venus work

See, if you can find one, The Book of Health A Practical Family Physician, 1898, by Robert W. Patton

see Is God a respecter of persons? : another look at the purity laws in Leviticus by Anne M. Adams , 2000 in BYU Library Holdings

www.PRB.org see also United Nations www.un.org

www.prb.org World Population Data Sheet2008; pages 7-15. http://www.prb.org/pdf08/08WPDS_Eng.pdf

Google Amnesty International, Sexual Slavery, PRB.org, United Nations, and search Wikipedia.org

See www.UN.org

See www.prb.org World Population Data Sheet 2008, page 3

Obermeyer, C.M. March 1999, Female Genital Surgeries: The Known and the Unknowable. Medical Anthropology Quaterly13, pages 79-106;p retrieved 5 December from http://www.anthrosource.net/doi/abs/10.1525/maq.1999.13.1.79

Interview with HB, 12 June, 2005

http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data–and–analysis/United–Nations–Surveys– onCrime–Trends–and–the–Operations–of–Criminal–Justice–Systems.html

Retrieved 5 December, 2008 from http://www.un.org/women/endviolence/docs/VAW.pdf , UNite To End Violence Against Women, Feb. 2008

Retrieved 5 December from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/statements/Diane%20White.pdf

American Community Survey <http://www.census.gov/Press– Release/www/releases/archives/income_wealth/010583.html

Retrieved 5 Dec., 2008 from the UNstats.org from The World’s Women 2005: Progress and Statistics http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/indwm/ww2005_pub/English; page 54

Retrieved 5 Dec., 2008 from the UNstats.org from The World’s Women 2005: Progress and Statistics http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/indwm/ww2005_pub/English/WW2005_chpt_4_Work_BW.pdf ; page 47

Retrieved 8 December , 2008 from http://www.prb.org/pdf/childrenwallchartfinal.pdf

see Subbarro, K. and Raney, L. 1993, “Social Gains from Female Education: A CrossNational Study” World Bank Discussion Papers 194; retrived from Eric ED 363542 on 8 December, 2008

retrieved 8 Dec 2008 from http://www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/afrec/subjindx/114sped3.htm

retrieved, 8 Dec 2008 from http://www.unicef.org/sowc99/

see http://www.unicef.org/sowc08/docs/sowc08.pdf

see http://www.unicef.org/sowc08/docs/sowc08_table_1.pdf

USA Today paper, 19 October, 2005 College Gender Gap Widens: 57% are Women retrieved 8 December 2008 from http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2005–10–19–male–college–cover_x.htm

retrieved 8 December, 2008 from “Projections of Education Statistics to 2016” http://nces.ed.gov/programs/projections/projections2016/sec2c.asp

http://nces.ed.gov/programs/projections/projections2016/sec4b.asp

see http://www.allied–physicians.com/salary_surveys/physician–salaries.htm

Retrieved from the American Medical Association 8 December, 2008 from “Table 1- Physicians By Gender (Excludes Students)” http://www.amaassn.org/ama/pub/category/12912.html

see http://societyofwomenengineers.swe.org/index.php

see http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#b00–0000

1 retrieved 8 December, 2008 from http://www.dol.gov/wb/factsheets/hitech02.htm

Retrieved 8 December, 2008 from table 786: “Doctorates Conferred By Characteristics of Recipients: 2005” from http://www.census.gov/compendia.statab/tables/08s0786.pdf

Retrieved 9 December, 2008 from http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan– newsnewspaper–daily–english–online/Entertainment/23–Nov–2008/European– countriestop–places–for–women–to–live/1

Retrieved 9 December, 2008 from http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan– newsnewspaper–daily–english–online/Entertainment/23–Nov–2008/European– countriestop–places–for–women–to–live/1; page 27