14

Citation

Gordon, K., & Melrose, S. (2013). Keeping clients safe on the night shift. Mental Health Practice, 16(5). 12-18.

Abstract

The night shift admission checklist helps night nurses to maintain a culture of safety when admitting a person to an inpatient mental health unit. Mental health symptoms can be pronounced on admission but, on night shift, nurses seldom have the opportunity to seek direction from experienced mental health practitioners. Routine safeguards are often adapted at night to promote clients’ sleep. Documentation to assess clients’ risks for self-harm, violence, comorbid medical conditions and prescribed medications may not be complete, although these are essential to maintain the person’s safety on the unit. Although each hospital will have individual admission policies, the checklist can be adapted to include these. This article discusses safety issues at night and presents a checklist designed to promote safe care during night-time admission.

Keywords

Admission checklist, inpatient mental health unit, night shift, safety

LIMITED GUIDANCE is available for night nurses admitting people from emergency departments. Drawing on our clinical practice knowledge, we have produced a checklist to support nurses during the often unpredictable process of admission to mental health inpatient units on the night shift.

At night, organisational factors can affect safe transitions. For example, environmental safeguards, including routine processes, can be rushed; paperwork to assess the person for self-harm, violence, comorbid medical conditions and prescribed medications may not be completed; and inadequate communication can contribute to medication errors. As a result, clients and staff may perceive inpatient mental health units to be unsafe. The checklist offers a set of questions that night nurses can readily use in their practice to help promote a culture of safety.

Guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline on service user experiences in the UK identified the importance of promoting safety in mental health inpatient services by pointing out that ‘transitions from one service to another may evoke strong emotions and reactions in people using mental health services’ (NICE 2011). Clients and families must often give information to several different professionals and, when transfers occur rapidly, processes for handover communication between services may not be straightforward. But, as yet, few tools are available to ensure that mental health units have the information they need to care safely for incoming service users, particularly on night shifts.

In 2006, Johnson and Delaney published a theory for ‘keeping the unit safe’ that identified how dimensions of ideology, space, time and people can influence safety on mental health inpatient units. These factors contribute to safety as follows:

- Ideology – believing that safety is closely aligned with a therapeutic environment.

- Space – maintaining visibility and regulating flow of people through different areas of the unit.

- Time – organising predictable patterns of admissions, activities and staff shifts.

- People – staffing units with a mix of seasoned staff who can assess escalating behaviour.

In addition to checking patients and their belongings, ‘suicide proofing’ involves thorough environmental tours of all areas

A main tenet of the ‘people’ dimension is to understand skills that experienced staff implement to formulate their assessments. Delaney and Johnson (2006) call for nurses to purposefully uncover and articulate the embedded clinical practice knowledge they use to manage everyday situations that keep units safe. In an effort to achieve this, we present a handover tool, framed as a checklist, to support nurses in one such situation – the unpredictable task of admitting a new person while on night shift. First, we discuss night shift safety issues. Next, we describe how clients and staff feel about unit safety. Then we present our night shift admission checklist (NSAC) for mental health admissions.

Systems of care

On inpatient mental health units, research suggests that organisational factors are associated with adverse event outcomes. Hanrahan et al (2010) concluded that better management skills, better nurse-doctor relationships, and lower client-to-nurse staffing ratios decreased adverse events, such as wrong medication, falls with injuries, complaints from service users and families, work-related staff injuries and verbal abuse directed at nurses.

Jayaram and Herzog (2009) emphasised that better systems of care are needed to prevent suicide, aggressive behaviour, the use of seclusion, the use of restraints, falls, absconding, complications when dealing with medical comorbidities, and medication errors. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Task Force on Patient Safety (2003) identified how systems of care are flawed and that a change toward a culture of safety is required to prevent adverse medication events, seclusion, restraint and suicide. Brickell et al (2009) stressed that effective communication, service integration and interprofessional collaboration, especially during handovers and transitions of care, are essential in preventing harm.

Clearly, system-wide policies, full complements of seasoned staff and communication among team members contribute to keeping patients and staff safe. However, on the night shift, staffing can be restricted, team communication opportunities can be limited and transitions of care can be atypical. Published literature offers night nurses little direction on coping with handovers, such as admitting patients from emergency departments, under these circumstances.

Environmental dangers

Suicide Routine processes for assessing environmental dangers and maintaining safeguards, such as checking clients’ belongings and all unit spaces for potentially harmful objects, might be rushed when nurses are called on to receive a person on a rapid admission from the emergency department. Items brought in by visitors during the evening shift may have gone undetected and clients may have stockpiled items for self-harm, with or without suicidal intent (Quirk et al 2006, O’Donovan 2007).

In addition to checking patients and their belongings, ‘suicide proofing’ involves thorough environmental tours of all areas of the unit (Cardell et al 2009). According to the Joint Commission Resources (2007), the root cause of 84 per cent of inpatient suicides was the physical environment; 75 per cent of these occurred in bathrooms, bedrooms and cupboards, with 86 per cent carried out by hanging from bathroom doors. At night, observation of bedrooms and other areas may not be thorough because of the dark and a fear of waking up clients.

The length of time people have alone has been linked to increased suicide attempts (Litman 1982) and night time offers people more opportunities to be alone than any other time of day. Formal observations, where mental health staff maintain frequent checks on all clients on the unit, consume nursing resources (Manna 2010). Implementing unit rounds to assess environmental dangers and maintaining patient observation leave nurses with only short periods of time in which they can interact with new service users.

Violence and restraint Incidents of aggression and violence are serious issues of concern in nursing and are more common on mental health inpatient units than in other settings (Laker et al 2010, Sturrock 2010). Most episodes of seclusion, restraint and assaults that occur in response to mental health symptoms take place soon after admission (Allen et al 2009).

Research indicates that mental health nurses who implement restraint are experiencing more frequent and more severe injuries, particularly when they carry out restraint later in the progression of aggression (Moylan and Cullinan 2011).

Short et al (2008) call for admitting psychiatrists to ensure orders for emergency medication administration are available to staff as clients move from one treatment setting to another. Nurses’ prompt administration of medication in response to escalating mental health symptoms may avert the distress associated with restraint measures (Kynoch et al 2009, Moylan 2009). Research also shows that nurses’ clinical decision making for ‘as needed’ (pro re nata – prn) medication is often based on previous experience and levels of knowledge (Usher et al 2010). Therefore, knowing that newly admitted people may well demonstrate unpredictable behaviour and that decisions about when to restrain or medicate are not straightforward, environmental support from a team of mental health clinicians provides valuable assistance. However, night nurses have few colleagues available to help them problem solve.

Documentation

People admitted at night can be expected to have fewer documented assessments than those admitted during day or evening shifts. Emergency department nurses may be less likely to record mental health behaviour on the night shift (Schumacher et al 2010). When service users deny thoughts of self-harm, non-mental health staff may not be aware that denying suicidal ideation does not necessarily mean that the individual is not a suicide risk. For example, access to means, recent clinical condition, past suicide history, evidence of poor coping, medication non-concordance, diagnosis, family adversity or social loss, living environment and substance misuse can all contribute to increased risk for suicide (Joint Commission Resources 2007).

Risk Furthermore, when individuals initially seem at low risk for violent behaviour, non-mental health staff may not fully document additional indicators. The presence of pervasive developmental disorder, such as autism or Asperger’s syndrome, can also make documentation of psychiatric symptoms challenging (Chaplin 2011, Matson and Shoemaker 2011, Krch-Cole et al 2012). Here, past levels of risk, previous dangerous behaviour, severity of mental illness, degree of impulsivity, level of insight, non-concordance with treatment, missed contact with clinicians, access to weapons and misuse of substances can all contribute to increased risk for violence. These should be assessed, documented and communicated in handovers between care settings (Ignelzi et al 2007). With rapid admissions at night, family members may not be around to offer their input in emergency department assessments, clients can be incoherent, sedated or exhausted.

At night, observation of bedrooms and other areas may not be thorough because of the dark and a fear of waking up clients

Physical health Documentation of comorbid medical conditions may also be abbreviated on night shift. Although seriously mentally ill people experience poor physical health to a greater extent than the general population, assessing physical health needs can be ignored or neglected in inpatient settings (Reeves et al 2010, Howard and Gamble 2011). Mental health status can exacerbate asthma (Roy-Byrne et al 2008), cardiovascular disease, cancer and perinatal complications (Weiss et al 2009). Individuals diagnosed with mental illness, particularly those with the dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance misuse, are at high risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV (Ngwena 2011). Service users may not be able to describe prescribed medications and treatment plans for either their medical or mental health conditions. In these instances, nurses are responsible for documenting that the history is incomplete and identifying areas that need further exploration the following day.

Medication errors A review by the APA’s committee on safety revealed that medication errors were second only to suicide as frequent sentinel events occurring during psychiatric care (Perez and Jayaram 2009) . The committee emphasised that medication errors on inpatient mental health units happened in large part because of inadequate communication, ‘especially at transition points in the treatment process. Situations that require particular vigilance include patient transfer among different levels or locations of treatment… between medical unit and mental health unit’. Night nurses can help prevent errors related to miscommunication of care orders written in the emergency department by reviewing these with the handover nurse before actually receiving the person on the unit (Branowicki et al 2003, Chevalier et al 2006, Henry and Foureur 2007).

Given the importance of admission documentation in providing safe care, night nurses’ assessment of clients’ risk of harm to self or others, their comorbid medical conditions and medications are critical. In addition to the challenges of working at a time when organisational factors may not be at their best, when maintaining environmental safeguards are particularly challenging and when vigilant documentation is required, night nurses also experience stress related to an inpatient mental health environment. In the following section, we comment on how service users and staff feel about safety.

Perceptions of safety

Anxiety related to the experience of admission can be heightened for people at night. Through the eyes of our clients, inpatient units can be seen as unsafe places, where they are subject to aggression, bullying, theft of their personal property and widespread use of drugs and alcohol (Jones et al 2010) . Having a violent patient near their bed is a major source of stress (Latha and Ravi Shankar 2011) . Institutional measures of control, such as seclusion and restraint, have been perceived as potentially harmful or traumatic, and may increase feelings of frustration and social exclusion which could, in turn, lead to aggression, self-harm and treatment refusal or deterrence (Grubaugh et al 2007, Bowers 2009, Stubbs et al 2009).

Inpatient units can trigger feelings of powerlessness and re-traumatisation, particularly among women who have experienced abuse, trauma and violence (Victorian Government Department of Human Services (VGDHS) 2008). Orientation strategies have been suggested for decreasing admission anxiety; for example, creating a buddying system where newly admitted individuals spend time with stable service users (Jones et al 2010), discussing the traumatic event with a staff member (Grubaugh et al 2007) and creating all-female spaces on the unit (VGDHS 2008). Once again, these options are less likely to be available at night.

Hospital-based nurses on inpatient mental health units have described their work environment as ‘perilous’ (Kindy et al 2005). They report high rates of emotional exhaustion and job strain (Leka et al 2010) . Staff can feel as though they are frequently subjected to violent and aggressive behaviour from clients and, fearing that they will be hurt, may feel disinclined to engage (Currid 2009). Incidents of self-harm can leave nurses feeling apprehensive and resentful (Thangavelu 2010). Education in compassionate aggression management techniques may play a role in helping nurses to cope with these situations (McGill 2006, Kynoch et al 2009, Lepping et al 2009, Moylan 2009), but the sessions would likely be held during the day shift. Scheduling may not allow night nurses to attend in-service training opportunities.

Handover tool

As the preceding discussion illustrates, night nurses face unique challenges during admissions. Pressure to decrease emergency waiting times can result in individuals being rapidly transferred into mental health unit beds. Transfer of care information may be incomplete. Managing these admissions in ways that maintain a culture of safety throughout the unit requires a complex understanding of mental health nursing skills, knowledge and attitudes.

Straightforward processes for communicating essential client information during handovers are critical (Nadzam 2009). One such process is a checklist. Checklists can help ‘ensure consistency and completeness in carrying out complex tasks’ (World Health Organization 2010). They also benefit nurses in that they have been known to minimise paperwork, reduce time pressures and avoid repetition (Reeves 2011).

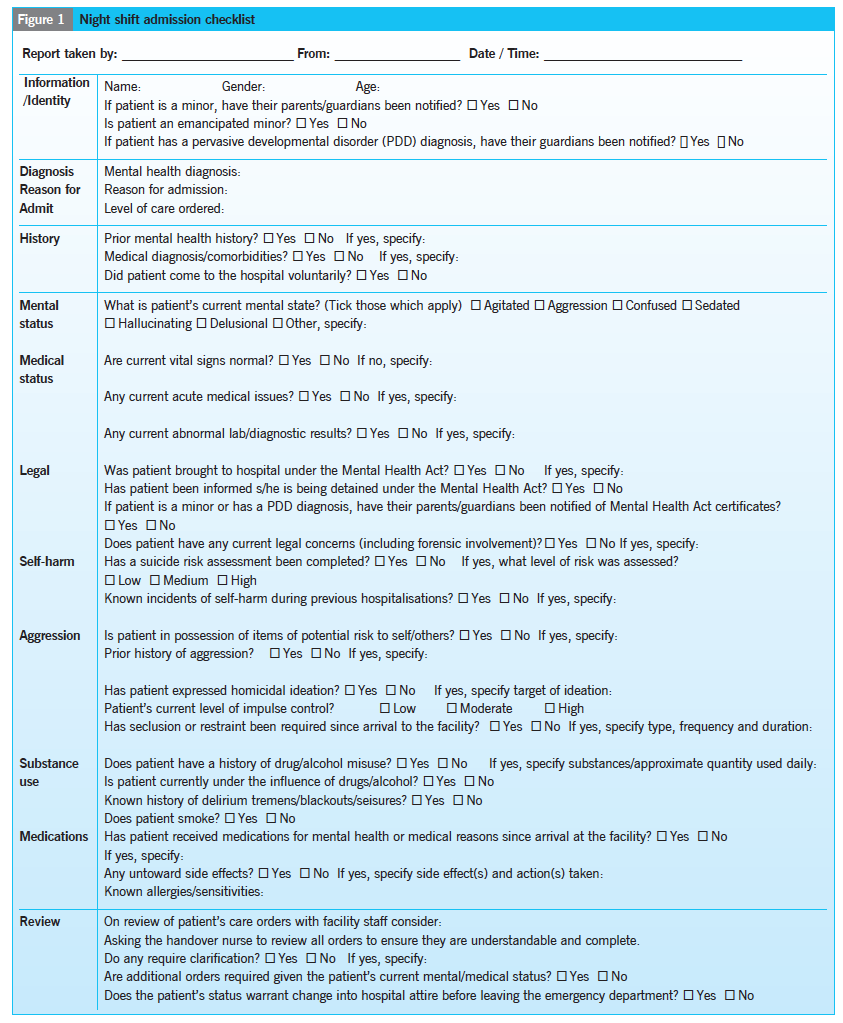

The following checklist (Figure 1) was created by the authors for our jurisdiction of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, through a process of consulting an administrator, a quality improvement consultant and nurse colleagues in mental health inpatient services. We also reviewed international literature on safe practices in mental health inpatient units and drew on our clinical practice experience.

Literature explaining organisational factors, environmental safeguards, documenting of assessments and of how service users and mental health nurses feel about safety all supported the development of the questions on the checklist.

For example, being aware that:

- Problematic organisational factors, such as medication errors, are associated with the restricted staffing expected on night shift.

- We posed questions to ensure that any medications received before arrival at the unit are communicated.

- High risk environmental safeguards, such as observing darkened private spaces, are difficult to manage on night shift. We posed questions to ensure that clients’ belongings are checked for objects they may use to harm themselves or others.

- Documenting assessments such as risk of self-harm, risk of violence and comorbid medical conditions can be abbreviated on night shift.

- We designed our questions to elicit information clearly targeting these critical areas. Since service users and nurses experience incidents of aggression, restraint and seclusion as highly stressful, we set questions to help identify untoward behaviours.

- Miscommunication in relation to patient care orders (medical instructions) can occur during transfers. We suggested that handover nurses should review client care orders with receiving nurses before clients arrive. Receiving nurses can clarify whether assessments and medications are complete or incomplete.

Feedback Anecdotal responses to the tool at our facility have been overwhelmingly positive, particularly for new and temporary staff. Our goal is to offer a starting point for other nurses to create a set of relevant questions. The checklist is designed to be an open-ended handover tool that responds to Delaney and Johnson’s (2006) call for nurses to uncover and articulate embedded clinical knowledge. We invite readers to review the checklist (Figure 1), evaluate its construction and consider what else could be included.

Conclusion

The checklist presented in this article was created from practical everyday knowledge that night nurses need in their effort to maintain a culture of safety when admitting someone from the emergency department. Mental health symptoms can be expected to be pronounced on admission and new clients may be likely to demonstrate behaviours that can be harmful to themselves or others. Routine safeguards in place during the day and evening shifts are often adapted at night to promote clients’ sleep: as a result service users and staff can feel unsafe. Assessment documentation may not be complete. Although each hospital will have individual admission policies, the checklist can be adapted to include these. The work extends existing knowledge about admission assessments by creating questions and highlighting priority issues that are unique to the night shift.

References

Allen D, Nesnera A, Souther J (2009) Executive-level reviews of seclusion and restraint promote interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 15, 4, 260-264.

American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Patient Safety (2003) Patient Safety and Psychiatry: Recommendations to the Board of Trustees of the American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA.

Bowers L (2009) A policy in conflict with the aims of patient care. Mental Health Practice. 12, 5, 12-13.

Branowicki P, O’Neill J, Dwyer J (2003) Improving complex medication systems: an interdisciplinary approach. Journal of Nursing Administration. 33, 4, 199-200.

Brickell T, Nicholls T, Procyshyn R et al (2009) Patient Safety in Mental Health. Canadian Patient Safety Institute and Ontario Hospital Association, Edmonton, AB.

Cardell R, Bratcher K, Quinnet P (2009) Revisiting ‘suicide proofing’ an inpatient unit through environmental safeguards: A review. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 45, 1, 36-44.

Chaplin R (2011) Mental health services for people with intellectual disabilities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24, 5, 372-376.

Chevalier B, Parker D, MacKinnon N et al (2006) Nurses’ perceptions of medication safety and medication reconciliation practices. Nursing Leadership. 19, 3, 61-72.

Currid T (2009) Experiences of stress among nurses in acute mental health settings. Nursing Standard. 23, 44, 40-46.

Delaney K, Johnson M (2006) Keeping the unit safe: Mapping psychiatric nursing skills. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 12,4, 198-207.

Grubaugh A, Frueh B, Zinzow H et al (2007) Patients’ perceptions of care and safety within psychiatric settings. Psychological Services. 4, 3, 193-201.

Hanrahan N, Kumar A, Aiken L (2010) Adverse events associated with organisational factors of general hospital inpatient psychiatric care environments. Psychiatric Services. 61, 6, 569-574.

Henry K, Foureur M (2007) A secondary care nursing perspective on medication administration safety. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 60, 1, 58-66.

Howard L, Gamble G (2011) Supporting mental health nurses to address the physical needs of people with serious mental illness in inpatient care settings. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 18, 2, 105-112.

Ignelzi J, Stinson B, Raia J et al (2007) Utilising risk-of-violence findings for continuity of care. Psychiatric Services. 58, 4, 452-454.

Jayaram G, Herzog A (2009) SAFE MD: Practical applications and approaches to safe psychiatric practice. Resource document of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Patient Safety. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington VA.

Johnson M, Delaney K (2006) Keeping the unit safe: a grounded theory study. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 12, 1, 13-21.

Joint Commission Resources (2007) Suicide Prevention: Toolkit for Implementing National Patient Safety Goal 15A. JCR, Oakbrook Terrace IL.

Jones J, Nolan P, Bowers L et al (2010) Psychiatric wards: Places of safety? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 17, 2, 124-130.

Kindy D, Petersen S, Parkhurst D (2005) Perilous work: Nurses’ experiences in psychiatric units with high risks of assault. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 19, 4, 169-175.

Krch-Cole E, Lynch P, Ailey S (2012) Clients with intellectual disabilities on psychiatric units: care coordination for positive outcomes. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 19, 3, 248-256.

Kynoch K, Wu C, Chang A (2009) The effectiveness of interventions in the prevention and management of aggressive behaviours in patients admitted to an acute hospital setting: a systematic review. Joanna Briggs Institute Library of Systematic Reviews. 7, 6, 175-223.

Laker C, Gray R, Flach C (2010) Case study evaluating the impact of de-escalation and physical training. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 17, 3, 222-228.

Latha K, Ravi Shankar B (2011) Hospital related stress among patients admitted to a psychiatric in-patient unit in India. Online Journal of Health Allied Sciences. www.ojhas.org/issue37/2011-1-5.htm (Last accessed: November 16 2012.)

Leka S, Hassard J, Yanagida A (2012) Investigating the impact of psychosocial risks and occupational stress on psychiatric hospital nurses’ mental well-being in Japan. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 19, 2, 123-131.

Lepping P, Needham I, Flammer E (2009) Ward safety perceived by ward managers in Britain, Germany and Switzerland: Identifying factors that improve ability to deal with violence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 16, 7, 629-635.

Litman R (1982) Hospital suicides: lawsuits and standards. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 12,4,212-220.

Manna M (2010) Effectiveness of formal observation in inpatient psychiatry in preventing adverse outcomes: the state of the science. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 17, 3, 268-273.

Matson J, Shoemaker M (2011) Psychopathology and intellectual disability. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24, 5, 367-371.

McGill A (2006) Evidence-based strategies to decrease psychiatric patient assaults. Nursing Management. 37, 11, 41-44.

Moylan L (2009) Physical restraint in acute care psychiatry. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing. 47, 3,41-47.

Moylan L, Cullinan M (2011) Frequency of assault and severity of injury of psychiatric nurses in relation to the nurses’ decision to restrain. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 8, 6, 526-534.

Nadzam D (2009) Nurses’ role in communication and safety. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 24, 3, 184-188.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Service User Experience in Adult Mental Health. NICE, London.

Ngwena J (2011) HIV/AIDS awareness in those diagnosed with mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 18, 3,213-220.

O’Donovan A (2007) Pragmatism rules: the intervention and prevention strategies used by psychiatric nurses working with non-suicidal self-harming individuals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 14, 1, 64-71.

Perez C, Jayaram G (2009) Drug/medication errors: examining risks to safe prescribing and use of medications. In Jayaram G, Herzog A (Eds) SAFE MD: Practical Applications and Approaches to Safe Psychiatric Practice. Resource document of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Patient Safety. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington VA.

Quirk A, Lelliot P, Seale C (2006) The permeable institution: an ethnographic study of three acute psychiatric wards in London. Social Science and Medicine. 63, 8, 2105-2117.

Reeves J (2011) Guidelines for recording the use of physical restraint. Mental Health Practice. 15, 1, 22-24.

Reeves R, Parker J, Burke, R (2010) Unrecognised physical illness prompting psychiatric admission. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 22, 3 180-185.

Roy-Byrne P, Davidson K, Kessler R et al (2008) Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. General Hospital Psychiatry. 30, 3, 208-225.

Schumacher J, Gleason S, Holloman G et al

(2010) Using a single-item rating scale as a psychiatric behavioural management triage tool in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 36, 5, 434-438.

Short R, Sherman M, Raia J et al (2008) Safety guidelines for injury-free management of psychiatric inpatients in precrisis and crisis situations. Psychiatric Services. 59, 12, 1376-1378.

Stubbs B, Leadbetter D, Paterson B et al (2009) Physical intervention: A review of the literature on its use, staff and patient views, and the impact of training. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 16, 1, 99-105.

Sturrock A (2010) Restraint in inpatient areas: the experiences of service users. Mental Health Practice. 14, 3, 22-26.

Thangavelu K (2010) Suicidal behavior among psychiatric inpatients. Mental Health Practice. 14, 4, 26-29.

Usher K, Baker J, Holmes C (2010) Understanding clinical decision making for PRN medication in mental health inpatient facilities. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 17, 6, 558-564.

Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2008) The Gender Sensitivity and Safety in Adult Acute Inpatient Units Project: Final Report. VGDH, Melbourne Australia.

Weiss S, Haber J, Horowitz J et al (2009) The inextricable nature of mental and physical health: Implications for integrative care. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 15, 6, 371-382.

World Health Organization (2010) Patient Safety: The Checklist Effect. WHO, Geneva.