Citation

Abstract

Mental health promotion activities that efficiently support persons with developmental disabilities (PDD) dually diagnosed with mental illness have been understudied. The co-occurrence of mental illness in PDD, also known as developmental disabilities (DD), as intellectual disabilities (ID) or more pejoratively as mental retardation (MR) is not well understood. According to the National Association for the Dually Diagnosed NADD (n.d.), dual diagnosis is a term applied to the co-occurrence of the symptoms of both PDD and mental illness. It is important to note that the term dual diagnosis is not used exclusively to identify the co-occurrence of PDD and mental illness. The overarching term dual diagnosis or co-morbidity is a generic term referring to the co-occurrence of disorders suffered by an individual (Telias, 2001).

Individuals identified as PDD experience difficulty functioning and adapting. Functionality is evaluated by an IQ score of 70 or below and adaptability by skill mastery in areas such as eating, dressing, communicating, socializing and assuming responsibility (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). PDD can be mild, moderate or severe. Traditionally, those with PDD were cared for in institutional settings. However, today nurses in the psychiatric field can routinely expect to meet community dwelling PDD clients in a variety of health care settings.

This paper describes a yearlong naturalistic action research project that implemented a WrapAround mental health promotion activity with six individuals dually diagnosed with a developmental disability and mental illness. Participants were drawn from two different Calgary agencies. Insights into the experiences of these clients, their families and the paid staff who care for them can help psychiatric nurses better understand and respond to this understudies group.

Background

Two key issues facing the dually diagnosed and those who care for them are a high prevalence of mental illness and perceived service gaps (Melrose, 2013).

High Prevalence of Mental Illness

Adults with intellectual disabilities can experience mental illness at a prevalence rate of 40.9%, nearly four times greater than the general population (Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Williamson & Allan, 2007). When admitted to psychiatric units, their problems can be more severe and they can receive more interventions than individuals without developmental disabilities (Chaplin, 2011). They may spend more days in hospital (Bouras, Martin, Leese, Vanstraelen, Holt et al, 2004; Morgan et al, 2008; Saeed, Ouellette-Kuntz, Stuart & Burge, 2003). The majority are likely to be subjected to chemical restraint (Webber, McVilly & Chan, 2011).

In Canada estimates suggest that 380,000 Canadians (Yu & Atkinson 1993, republished in 2006) and between 6,000 and 13,000 Albertans live with a dual diagnosis (Hughson, 2009). About forty-two percent of all hospitalizations among PDD Canadians occurred for psychiatric conditions (Lunsky & Balogh, 2010). PDD Canadians are at fifteen times greater risk of receiving a psychiatric admission of schizophrenia (Balogh, Brownell, Ouellette-Kuntz et al. 2010), and this risk is also nearly four times greater than the general population (Morgan, Leonard, Bourke & Jablensky, 2008). Further, PDD Canadians are at over four times greater risk of experiencing dementia and at nearly three times higher risk of being depressed than non PDD individuals (Shooshtari, Martens, Burchill et al. 2011). Fourteen per cent of PDD participants in an Australian study had an incapacitating anxiety disorder (White, Chant, Edwards, Townsend, Waghorn, 2005). The high prevalence rate of developmental disabilities co-occurring with mental illness is further influenced by traumatic events, challenging behaviors and assessment issues.

Traumatic events Adults whose intellectual disability is mild or moderate, rather than severe, may not have greater prevalence rates than the general population (Whittaker & Read, 2006). However, traumatic events can also play an important role in their psychopathology. In one study, 75% of participants with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities had all experienced at least one traumatic event during their life span, predisposing them to significantly increased probability of a mental disorder (Martorell et al, 2009).

Challenging behaviors Challenging behaviors, although not listed as DSM-IV-TR psychiatric diagnosis, have consistently been identified as a reason for admission to hospital (Cooper et al 2007; Cooper, Smiley, Allan, Jackson, Finlayson et al, 2009; Cooper, Smiley, Jackson, Finlayson, Allan et al, 2009; Whittaker & Read, 2006). Challenging or problem behaviors such as aggression, self-injury, and destructive, disruptive or non-compliant behaviors often precipitate hospitalization (Lowe, Allen, Jones, Brophy, Moore & James, 2007). However, while challenging behaviors coexist in some people with intellectual disability, disturbances in psychiatric functioning are not believed to underpin the majority of these behaviors (Allen & Davies, 2007).

Assessment issues Assessing mental illness among persons with intellectual disabilities is not straightforward. Limited training is available to professionals (Quintero & Flick, 2010). In turn, mental illness may go undetected in PDD. Many diagnostic criteria include self reports of thoughts, feelings, physiologic states, past events and reactions to these events. This requires a level of language discrimination and memory skills that may not be present in adults with intellectual disabilities (Bouras & Holt, 2007). Diagnostic overshadowing, or ignoring mental health problems because the symptoms are judged to be “just” part of the developmental disability, can occur (Reiss & Szyszko, 1983). The social isolation often accompanying PDD can leave individuals with distorted perceptions of whether what they are experiencing is ‘normal’ (Silka & Hauser, 1997). Hospital emergency department staff reported a lack of knowledge related to intellectual disabilities (Lunsky, Gracey, & Gelfand, 2008) and paid caregivers need training in the early detection and warning signs of mental ill health (Smiley, Cooper, Finlayson, Jackson, Allan et al, 2007). Canadian online resources such as the text: Introduction to the Mental Health Needs of Persons with Developmental Disabilities (Griffiths, Stavrakaki & Summers, 2002), and the guidelines: Planning Guidelines for Mental Health and Addiction Services for Children, Youth and Adults with Developmental Disability (BC Ministry of Health, 2007 March) begin to offer important direction.

Perceived Service Gaps

Deficiencies In a national survey examining the range of mental health services available to individuals with a dual diagnosis and perceived service gaps across Canada, respondents identified that generic mental health providers were poorly equipped to meet the needs of these individuals, that wait lists for specialized services were typically four months or longer and less than half of the respondents affirmed that expertise or specialized services existed in inpatient treatment or emergency room facilities (Lunsky, Garcin, Morin, Cobigo, & Bradley, 2007). Aggression/challenging behavior was the main reason for admission to and barrier to discharge from hospital (Lunsky & Puddicombe, 2005, December). An inability to access appropriate mental health services in a timely manner leads to crises resulting in hospital emergency room visits, warranting intervention to correct the deficiencies at both the clinical and systems levels (Lunsky, Gracey, & Gelfand, 2008).

Beyond medication Researchers continue to question the efficacy of psychotropic medication treatments for dually diagnosed clients who present with challenging behaviors (Antonacci, Manuel & Davis; Benson & Brooks, 2008; Tyrer et al, 2008) and yet, as many as half of the adults in this population have been prescribed psychotropic medication (Lunsky, Emery, & Benson, 2002). They may not believe they have either choice or involvement in their medication regime (Crossley & Withers, 2009). Services that include but are not limited to prescribing medication are needed.

Clearly, high rates of psychiatric unit admissions are occurring among this population and gaps in service are perceived. Our research aimed to implement and evaluate an alternative approach that focused on health promotion.

Approach and Methods

Our project was framed from a strengths based conceptual perspective (Rapp, Saleebey & Sullivan, 2005; Saleebey, 2006) and a naturalistic action research design (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1990). Action research implements and then evaluates new ideas in practice and asks the question ‘what can we do better?’ (Kiener & Koch, 2009). Our research posed the question: What can we do better to prepare PDD clients to anticipate and prevent a psychiatric mental health crisis before hospitalization occurs. Participants were recruited from two Calgary agencies serving PDD clients.

Ethical approval was obtained from Athabasca University. Ten clients identified as dually diagnosed by agency staff were invited to participate and four declined. As Clements (2012) emphasized, participating clients’ capacity for in-formed consent was assessed and obtained throughout the project and all participants were given the opportunity to discontinue their involvement at any time.

Modeling the action research intervention on a ‘Wrap-Around’ approach, facilitators provided monthly health promotion meetings to six PDD clients at risk of experiencing a psychiatric mental health crisis. Individually, each client was helped to create a team of family members and paid caregivers to “wrap around’ them. Throughout 2012, the six teams met regularly and facilitators guided discussions to focus on clients’ strengths, their goals and individualized strategies for success.

The WrapAround approach is an intensive, holistic method of engaging with individuals with complex needs so that they can live in their homes and communities and realize their hopes and dreams (National WrapAround Initiative, n.d.). The approach is a client driven, team oriented planning model. Typically used with children, youth and their families, this project is unique in adapting the model to PDD clients. The approach espouses:

“a philosophy of care beginning from the principle of ‘voice and choice,’ which stipulates that the perspectives of the family—including the [client] — must be given primary importance … Values …[emphasize] supports that are individualized, family driven, culturally competent, and community based. The process should increase the ‘natural support’ available to a family by strengthening inter-personal relationships and utilizing other resources available in the family’s network of social and community relationships. It should be ‘strengths based,’ including activities that purposefully help the [client] and family to recognize, utilize, and build talents, assets, and positive capacities” (National WrapAround Initiative, n.d. ¶3).

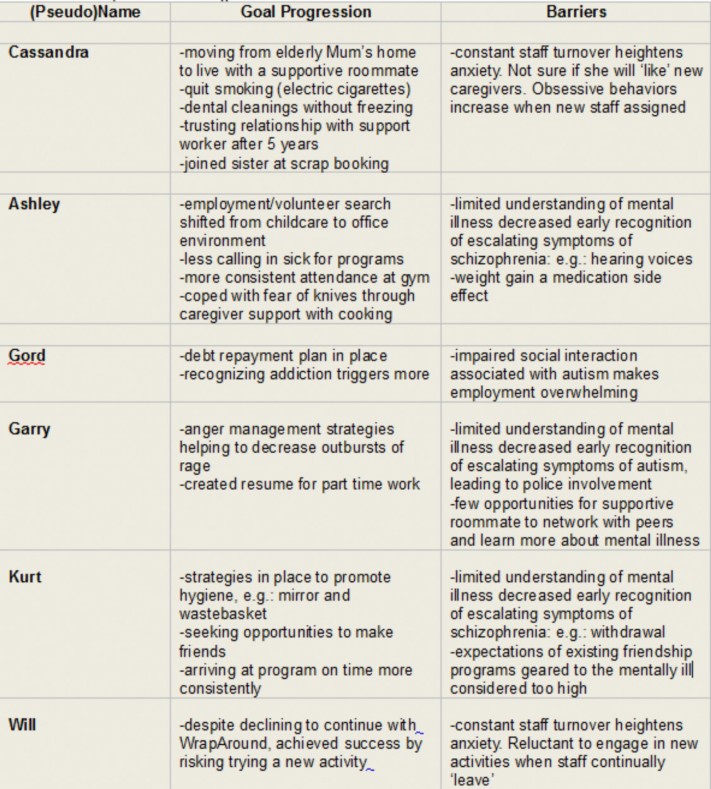

Table 1 presents indicators of some of the goal progression and barriers the teams identified and that led to the creation of the themes.

Facilitators closed the project by reviewing the efficacy of the intervention (the WrapAround team approach) and exploring barriers that participants experienced. Each client and at least one member of their WrapAround teams were interviewed by a researcher not involved with their teams or with the agency providing their care. Transcripts of the interviews were used as data sources. The interview transcripts were analyzed using line by line coding to create categorizations that led to themes. QRS International’s NVivo 10 was used to organize the data collection and analysis. Trustworthiness was established by member checking with the participants to ensure authenticity.

Key Findings

Three themes emerged from discussions with both PDD clients who are at risk of experiencing a mental health crisis; and the family members and/or paid caregivers on their Wrap Around teams.

- Regular meetings where clients seek and receive support from individuals they value can help address escalating symptoms of mental illness.

- Constant caregiver turnover heightens client anxiety, which in turn exacerbates illness.

- Limited paid in-service and networking opportunities are available to caregivers.

Table 1 (page 34) presents indicators of some of the goal progression and barriers the teams identified and that led to the creation of the themes.

Discussion

This action research project illustrated a nurse led health promotion approach that participants found helpful. The researchers provided participants with monthly meetings where support teams ‘wrapped around’ clients and supported them towards success. Rather than responding to clients in crisis, the monthly meetings created opportunities for family and paid caregivers to support well clients. The regular meetings created opportunities to address clients’ escalating symptoms of mental illness when they first appeared, thus preventing costly hospitalizations. As a psychiatric nursing intervention, monthly health promotion meetings illustrate valued support for at risk PDD clients.

Discussions with clients and their WrapAround team members revealed the impact that constant caregiver turnover has on clients’ health. One caregiver identified a

40% yearly staff turnover in her program. A family member explained how adjusting to 18 to 20 new caregivers in a three year period heightened her loved one’s anxiety. Clients, family members and caregivers all agreed that this anxiety in turn exacerbated illness.

Constant staff turnover is an unresolved issue for those who care for the developmentally disabled. Reports emphasize how funding cuts, limited staff training and poor working conditions result in high staff turnover in other Canadian jurisdictions as well (Casey, 2011; Hendren, 2011, July: Hensel, Lunsky & Dewa, 2011, February; Li, 2004). The present study contributes to a growing body of knowledge indicating that constant staff turnover is clearly a problem in the field.

Most caregivers interviewed in this project noted that they are paid only for face to face time with clients. Therefore, professional development opportunities such as in-services, workshops and networking opportunities with colleagues and other professionals are not available to them. Several had no pre-service education and/or training in either developmental disabilities or mental illness. They often felt that they did not know what to do when clients presented with challenging behaviours. They expressed that recognizing escalating symptoms of mental illness was difficult and indicated their willingness to learn more.

Responding to clients’ challenging behaviours leave direct care staff, particularly those who are untrained, feeling emotionally exhausted and burned out (Chung & Harding, 2009; Jenkins, Rose, & Lovell, 1997; Thomas & Rose, 2010 ). Some resolution of staff’s emotional exhaustion has been achieved through training focusing on understanding the psychiatric conditions underlying clients’ challenging behaviours (Costello, Bouras & Davis, 2007; Rose, Rose & Kent, 2012; Werner & Stawski, 2012). Knowing that this training may help resolve the issue of constant staff turnover, opportunities for psychiatric nurses to contribute their expertise become apparent. Creating individually accessible educational resources for paid caregivers is an area where psychiatric nurses can provide much needed support.

Conclusion

Persons with developmental disabilities and co-occurring mental illness benefit from long term, scheduled health promotion meetings and their paid caregivers are often uninformed about escalating symptoms of psychiatric illness. Resources to help paid caregivers recognize and understand mental illness within this client group are urgently needed. Psychiatric nurses are well positioned to initiate health promotion activities such as the WrapAround intervention presented in this paper. Psychiatric nurses are equally well positioned to create individually accessible resources for clients’ paid caregivers. In contrast to other studies emphasizing psychotropic medication and hospital based treatment, this project illustrates an alternative intervention focusing on crisis prevention. We invite readers to consider similar opportunities where psychiatric nurses could provide support to dually diagnosed clients and those who care for them.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Test Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: Author.

Allen, D. & Davis, D. (2007). Challenging behaviour and psychiatric disorder in intellectual disability Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(5), 450-455.

Antonacci, DJ., Manuel, C., & Davis, E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of aggression in individuals with developmental disabilities. Psychiatric Quarterly, 79(3), 225-247.

Balogh, R., Brownell, M., Ouellette-Kuntz, H, et al. (2010). Hospitalisation rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions for persons with and without an intellectual disability: A population perspective. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54 (9), 820–832.

BC Ministry of Health (2007, March). Planning guidelines for mental health and addiction services for children, youth and adults with developmental disability. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Mental Health and Addictions Branch. Available at http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2007/MHA_Developmental_Disability_Planning_Guidelines.pdf

Benson, B., Brooks, W. (2008). Aggressive challenging behaviour and intellectual disability. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(5), 454-458.

Bouras, N., & Holt, G. (2007). Psychiatric and behavioural disorders in intellectual and developmental disabilities (2nd ed), New York, Cambridge University Press.

Bouras, N., Martin, G., Leese, M., Vanstraelen, M., Holt, G., Thomas, C., Hindler, C., Boardman, J. (2004). Schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses in people with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48, 548-55.

Casey, R. (2011). Burnout for developmental services workers. McGill Sociological Review, 2, 39-58.

Chaplin, R. (2011) . Mental health services for people with intellectual disabilities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(5), 372-6.

Chung, M. C. & Harding, C. (2009). Investigating burnout and psychological well-being of staff working with people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: The role of personality. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 549–560. doi: 10.1111/j.14683148.2009.00507.x

Clements, K. (2012). Ethical research guidelines and psychiatric nursing. Canadian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 1, 81-84.

Cooper, S., Smiley, E., Allan, L., Jackson, A., Finlayson, J., Mantry, D., Morrison, J. (2009). Adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence, incidence and remission of self-injurious behaviour, and related factors Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53 (3), 200-216.

Cooper, S., Smiley, E., Jackson, A., Finlayson, J., Allan, L., Mantry, D., Morrison, J. (2009). Adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence, incidence and remission of aggressive behaviour and related factors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(3), 217-232.

Cooper, S., Smiley, E., Morrison, J., Williamson, A., & Allen, L. (2007). Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 27-35.

Costello, H., Bouras, N. & Davis, H. (2007). The role of training in improving community care staff awareness of mental health problems in people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00320.x

Crossley, R., & Withers, P. (2009). Antipsychotic medication and people with intellectual disabilities: Their knowledge and experiences. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 77-86.

Griffiths, D., Stavrakaki,C., & Summers, J. (Eds.). (2002). An introduction to the mental health needs of persons with developmental disabilities. Sudbury, ON: National Association for the Dually Diagnosed, Ontario Chapter Ontario, Habilitative Mental Health Resource Network. Available at http://www.naddontario.net/publications/

Hendren, A. (2011, July). Services to people with developmental disabilities: Contemporary challenges and necessary solutions. BC

Community Living Action Group: Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Hensel, J., Lunsky, Y. & Dewa, C. (2011, February). A provincial study of direct support staff who work with adults with developmental disabilities in Ontario: The experience of client aggression and its emotional impact on staff. Research and Evaluation Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: Toronto, ON, Canada.

Hughson, A. (2009). Collaborative Research Grant Initiative: Mental wellness in seniors and persons with disabilities: System capability to respond to those with complex needs Persons with Disabilities. Calgary: Alberta Mental Health Research Partnership Program.

Jenkins, R., Rose, J. & Lovell, C. (1997). Psychological well-being of staff working with people who have challenging behavior. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 41, 502–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00743.x

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1990). The action research reader (3 ed.). Victoria, Australia: Deacon University Press.

Kiener, M. & Koch, L. (2009). Action research in rehabilitation counseling, Journal of Rehabilitation Counseling, 40(3), 19-26.

Li, S. (2004). Direct care personnel recruitment, retention, and orientation. Community-University Institute for Social Research: Saskatoon, SK, Canada.

Lowe, K., Allen, D., Jones, E., Brophy, S., Moore, K. & James, W. (2007). Challenging behaviours: Prevalence and topographies. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(8), 625-636.

Lunsky, Y., Emery, C. & Benson, B. (2002). Staff and self-reports of health behaviours, somatic complaints and medications among adults with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability, 27(2) 125-153.

Lunsky, Y., Garcin, N., Morin, D., Cobigo, V., & Bradley, E. (2007). Mental health services for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Canada: Findings from a National Survey. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(5), 439-447.

Lunsky, Y., Gracey, C., & Gelfand, S. (2008). Emergency psychiatric services for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Perspectives of hospital staff. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 46(6), 446-455.

Lunsky, Y., & Puddicombe, J. (2005, December). Dual diagnosis in Ontario’s specialty (psychiatric) hospitals: Qualitative findings and recommendations, Phase II Summary Report. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Lunsky, Y., & Balogh, R. (2010). Dual diagnosis: A national study of psychiatric hospitalization patterns of people with developmental disability. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(11), 721– 728.

Martorell, A., Tsakanikos, E., Pereda, A., Gutiérrez-Recacha, P., Bouras, N., Ayuso-Mateos, J. (2009). Mental health in adults with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities: The role of recent life events and traumatic experiences across the life span, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(3), 182-186.

Melrose, S. (2013). Developmental disabilities co-occurring with Mental illness. Knowledge Notes, KN-11, January. Alberta Addiction and Mental Health Research Partnership Program Publication. Available http://www.mentalhealthresearch.ca/Publications/Documents/KN-11_Developmental_Disabilities_Co-occurring_with_Mental_Illness_Jan2013.pdf

Morgan, V., Leonard, H., Bourke, J., & Jablensky, A. (2008). Intellectual disability co-occurring with schizophrenia and other psychiatric illness: Population-based study, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193, 364-372.

National Association for the Dually Diagnosed NADD (n.d.). Information on dual diagnosis [Fact Sheet]. Available from the NADD website http://thenadd.org/resources/information-on-dual-diagnosis/

National WrapAround Initiative (n.d.). WrapAround Basics. Retrieved from the National WrapAround Initiative, Retrieved from Portland Oregon website http://www.nwi.pdx.edu/wraparoundbasics.shtml

Quintero, M., & Flick, S. (2010). Co-occurring mental illness and developmental disabilities. Social Work Today, 10(5), 6.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QRS International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2013.

Rapp, C. A., Saleebey, D., & Sullivan, W. P. (2005). The future of strengths-based social work. Advances in Social Work, 6(1), 79-90.

Reiss, S. & Szyszko, J. (1983). Diagnostic overshadowing and professional experience with mentally retarded persons. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 87, 396–402.

Rose, N., Rose, J. & Kent, S. (2012). Staff training in intellectual disability services: A review of the literature and implications for mental health services provided to individuals with intellectual disability. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities,58(1), 24–39.

Saeed, H., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Stuart, H., & Burge, P. (2003). Length of stay for psychiatric inpatient services: A comparison of admissions of people with and without developmental disabilities, The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 30(4), 406-417.

Saleebey, D. (2006). The strengths perspective in social work practice (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Shooshtari, S., Martens, P., Burchill, C., Dik, N., & Naghipur, S. (2011). Prevalence of depression and dementia among adults with developmental disabilities in Manitoba, Canada. International Journal of Family Medicine, Vol 2011, Article ID 319574. Available at http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijfm/2011/319574/ref/

Silka, V. & Hauser, M. (1997). Psychiatric assessment of the person with mental retardation. Psychiatric Annals, 27(3),162-169.

Smiley, E., Cooper, S., Finlayson, J., Jackson, A., Allan, Mantry, D., McGrother, C., McConnachie, A & Morrison, J. (2007). Incidence and predictors of mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: Prospective study, British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 313-319.

Telias, D. (2001). Dual diagnosis. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 5, 101-110.

Thomas, C. & Rose, J. (2010). The relationship between reciprocity and the emotional and behavioural responses of staff. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23, 167–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00524.x

Tyrer, P., Oliver-Africano, P., Ahmed, Z., Bouras, N., Cooray, S., Deb, S., et al (2008). Risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the treatment of aggressive challenging behaviour in patients with intellectual disability: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 371, 57-63.

>Webber, L. S., McVilly, K. R. & Chan, J. (2011). Restrictive interventions for people with a disability exhibiting challenging behaviours: Analysis of a population database. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24(6), 495–507.

Whitaker, S. & Read, S. (2006). The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among people with intellectual disabilities: An analysis of the literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 330-345.

Werner, S. & Stawski, M. (2012). Mental health: Knowledge, attitudes and training of professionals on dual diagnosis of intellectual disability and psychiatric disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56, 291–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01429.x

White P, Chant D, Edwards N, Townsend C, Waghorn G. (2005). Prevalence of intellectual disability and comorbid mental illness in an Australian community sample. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39, 395-400.

Yu, D. & Atkinson, L. (1993, republished in 2006). Developmental disability with and without psychiatric involvement: Prevalence estimates for Ontario. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, Spring, 1–6.