23 Product and Handling Hazards

Learning Objectives

Identify product handling hazards

Food handling and Storage Procedures

Proper food handling and storage can prevent most foodborne illnesses. In order for pathogens to grow in food, certain conditions must be present. By controlling the environment and conditions, even if potentially harmful bacteria are present in the unprepared or raw food, they will not be able to survive, grow, and multiply, causing illness.

There are six factors that affect bacterial growth, which can be referred to by the mnemonic FATTOM:

- Food

- Acid

- Temperature

- Time

- Oxygen

- Moisture

FATTOM

Each of these factors contributes to bacterial growth in the following ways:

- Food: Bacteria require food to survive. For this reason, moist, protein-rich foods are good potential sources of bacterial growth.

- Acid: Bacteria do not grow in acidic environments. This is why acidic foods like lemon juice and vinegar do not support the growth of bacteria and can be used as preservatives

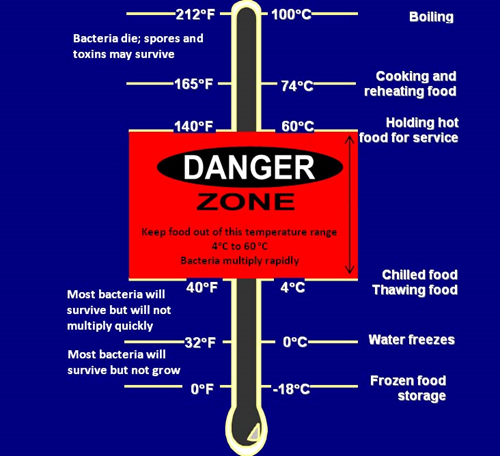

- Temperature: Most bacteria will grow rapidly between 4°C and 60°C (40°F and 140°F). This is referred to as the danger zone (see the section below for more information on the danger zone).

- Time: Bacteria require time to multiply. When small numbers of bacteria are present, the risk is usually low, but extended time with the right conditions will allow the bacteria to multiply and increase the risk of contamination

- Oxygen: There are two types of bacteria. Aerobic bacteria require oxygen to grow, so will not multiply in an oxygen-free environment such as a vacuum-packaged container. Anaerobic bacteria will only grow in oxygen-free environments. Food that has been improperly processed and then stored at room temperature can be at risk from anaerobic bacteria. A common example is a product containing harmful Clostridium botulinum(botulism-causing) bacteria that has been improperly processed during canning, and then is consumed without any further cooking or reheating.

- Moisture: Bacteria need moisture to survive and will grow rapidly in moist foods. This is why dry and salted foods are at lower risk of being hazardous.

Identifying Potentially Hazardous Foods (PHFs)

Foods that have the FATTOM conditions are considered potentially hazardous foods (PHFs). PHFs are those foods that are considered perishable. That is, they will spoil or “go bad” if left at room temperature. PHFs are foods that support the growth or survival of disease-causing bacteria (pathogens) or foods that may be contaminated by pathogens.

Generally, a food is a PHF if it is:

- Of animal origin such as meat, milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, poultry (or if it contains any of these products)

- Of plant origin (vegetables, beans, fruit, etc.) that has been heat-treated or cooked

- Any of the raw sprouts (bean, alfalfa, radish, etc.)

- Any cooked starch (rice, pasta, etc.)

- Any type of soya protein (soya milk, tofu, etc.)

The following table identifies common foods as either PHF or non-PHF.

| PHF | Non-PHF |

| Chicken, beef, pork, and other meats | Beef jerky |

| Pastries filled with meat, cheese, or cream | Bread |

| Cooked rice | Uncooked rice |

| Fried onions | Raw onions |

| Opened cans of meat, vegetables, etc. | Unopened cans of meat, vegetables, etc. (as long as they are not marked with “Keep Refrigerated”) |

| Tofu | Uncooked beans |

| Coffee creamers | Cooking oil |

| Fresh garlic in oil | Fresh garlic |

| Fresh or cooked eggs | Powdered eggs |

| Gravy | Flour |

| Dry soup mix with water added | Dry soup mix |

The Danger Zone

One of the most important factors to consider when handling food properly is temperature. The following table lists the most temperatures to be aware of when handling food.

| Celsius | Fahrenheit | What happens? |

| 100° | 212° | Water boils |

| 60° | 140° | Most pathogenic bacteria are destroyed. Keep hot foods above this temperature. |

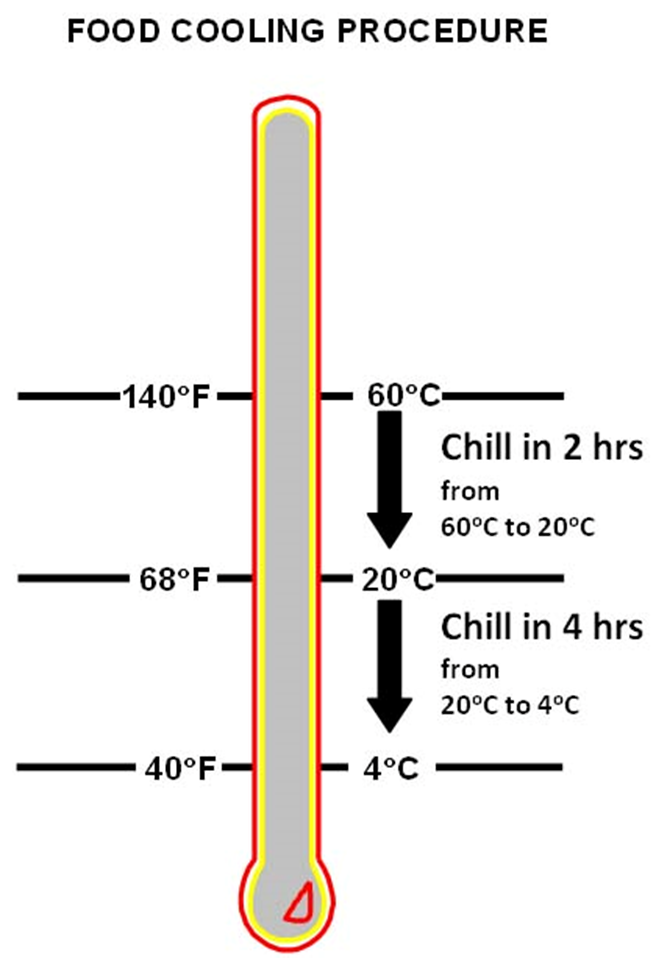

| 20° | 68° | Food must be cooled from 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 68°F) within two hours or less |

| 4° | 40° | Food must be cooled from 20°C to 4°C (68°F to 40°F) within four hours or less |

| 0° | 32° | Water freezes |

| –18° | 0° | Frozen food must be stored at −18°C (0°F) or below |

The range of temperature from 4°C and 60°C (40°F and 140°F) is known as the danger zone, or the range at which most pathogenic bacteria will grow and multiply.

Time-temperature Control of PHFs

Pathogen growth is controlled by a time-temperature relationship. To kill microorganisms, food must be held at a sufficient temperature for a sufficient time. Cooking is a scheduled process in which each of a series of continuous temperature combinations can be equally effective. For example, when cooking a beef roast, the microbial lethality achieved at 121 minutes after it has reached an internal temperature of 54°C (130°F) is the same as if it were cooked for 3 minutes after it had reached 63°C (145°F).

The following table shows the minimum time-temperature requirements to keep food safe. (Other time-temperature regimens might be suitable if it can be demonstrated, with scientific data, that the regimen results in safe food.)

| Critical control point | Type of food | Temperature |

| Refrigeration | Cold food storage, all foods. | 4°C (40°F) or less |

| Freezing | Frozen food storage, all foods. | −18°C (0°F) or less |

| Freezing | Parasite reduction in fish intended to be served raw, such as sushi and sashimi | −20°C (−4°F) for 7 days or −35°C (−31°F) in a blast freezer for 15 hours |

| Cooking | Food mixtures containing poultry, eggs, meat, fish, or other potentially hazardous foods | Internal temperature of 74°C (165°F) for at least 15 seconds |

| Cooking | Rare roast beef | Internal temperature of 54°C to 60°C (130°F to 140°F) |

| Cooking | Medium roast beef | Internal temperature of 60°C to 65°C (140°F to 150°F) |

| Cooking | Pork, lamb, veal, beef (medium-well) | Internal temperature of 65°C to 69°C (150°F to 158°F) |

| Cooking | Pork, lamb, veal, beef (well done) | Internal temperature of 71°C (160°F) |

| Cooking | Poultry | Internal temperature of 74°C (165°F) for 15 seconds |

| Cooking | Stuffing in poultry | 74°C (165°F) |

| Cooking | Ground meat (Includes chopped, ground, flaked, or minced beef, pork, or fish) | 70°C (158°F) |

| Cooking | Eggs[1] | 63°C (145°F) for 15 seconds |

| Cooking | Fish[2] | 70°C (158°F) |

| Holding | Hot foods | 60°C (140°F) |

| Cooling | All foods | 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 68°F) within 2 hours and 20°C to 4°C (68°F to 40°F) within 4 hours |

| Reheating | All foods | 74°C (165°F) for at least 15 seconds |

The Top 10 List: Do’s and Don’ts

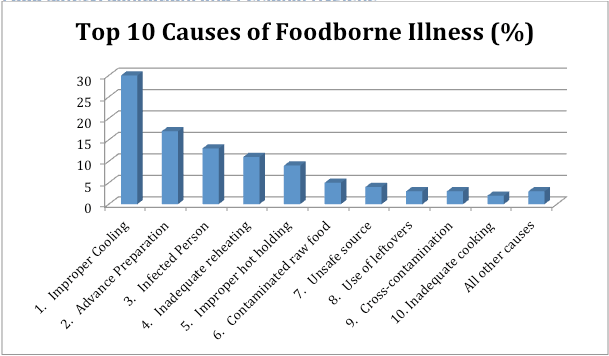

The following figure illustrates the top 10 improper food-handling methods and the percentage of foodborne illnesses they cause.

This section describes each food-handling practice outlined in the top 10 list and the ways to prevent each problem.

Improper cooling

Many people think that once food has been properly cooked, all disease-causing organisms (pathogens) have been killed. This is not true. Some pathogens can form heat-resistant spores, which can survive cooking temperatures. When the food begins cooling down and enters the danger zone, these spores begin to grow and multiply. If the food spends too much time in the danger zone, the pathogens will increase in number to the point where the food will make people sick. That is why the cooling process is crucial. Cooked food must be cooled from 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 70°F) in two hours or less, AND then from 20°C to 4°C (70°F to 40°F) in four hours or less.

Infected person

Many people carry pathogens somewhere on or in their bodies without knowing it—in their gut, in their nose, in their hands, in their mouth, and in other warm, moist places. People who are carrying pathogens often have no outward signs of illness. However, people with symptoms of illness (diarrhea, fever, vomiting, jaundice, sore throat with a fever, hand infections, etc.) are much more likely to spread pathogens to food.

Another problem is that pathogens can be present in cooked and cooled food that, if given enough time, can still grow. These pathogens multiply slowly but they can eventually reach numbers where they can make people sick. This means that foods that are prepared improperly, many days before serving, yet stored properly the entire time can make people sick.

Some pathogens are more dangerous than others (e.g., salmonella, E. coli, campylobacter). Even if they are only present in low numbers, they can make people very sick. A food handler who is carrying these kinds of pathogens can easily spread them to foods – usually from their hands. Ready-to-eat food is extra dangerous. Ready-to-eat food gets no further cooking after being prepared, so any pathogens will not be killed or controlled by cooking.

To prevent problems:

- Make sure all food handlers wash their hands properly after any job that could dirty their hands (e.g., using the toilet, eating, handling raw meats, blowing their nose, smoking).

- Food handlers with infected cuts on their hands or arms (including sores, burns, lesions, etc.) must not handle food or utensils unless the cuts are properly covered (e.g., waterproof bandage covered with a latex glove or finger cot).

- When using gloves or finger cots, food handlers must still wash their hands. As well, gloves or cots must be replaced if they are soiled, have a hole, and at the end of each day.

- Food handlers with infection symptoms must not handle utensils or food and should be sent home.

- Where possible, avoid direct hand contact with food – especially ready-to-eat foods (e.g., use plastic utensils plastic or latex gloves).

Unsafe source

Foods from approved sources are less likely to contain high levels of pathogens or other forms of contamination. Approved sources are those suppliers that are inspected for cleanliness and safety by a government food inspector. Foods supplied from unreliable or disreputable sources, while being cheaper, may contain high levels of pathogens that can cause many food-poisoning outbreaks.

Fly-by-night suppliers (trunk sales) often do not care if the product is safe to sell to you, but approved suppliers do! As well, many fly-by-night suppliers have obtained their product illegally (e.g., closed shellfish fisheries, rustled cattle, poached game, and fish) and often do not have the equipment to properly process, handle, store, and transport the food safely.

Of particular concern is seafood from unapproved sources. Seafood, especially shellfish, from unapproved sources can be heavily contaminated with pathogens or poisons if they have been harvested from closed areas.

To prevent problems:

- Buy your food and ingredients from approved sources only. If you are not sure a supplier has been approved, contact your local environmental health officer. He or she can find out for you.

- Do not take the chance of causing a food-poisoning outbreak by trying to save a few dollars. Remember, your reputation is on the line.

Cross-contamination

You can expect certain foods to contain pathogens, especially raw meat, raw poultry, and raw seafood. Cross-contamination happens when something that can cause illness (pathogens or chemicals) is accidentally put into a food where not previously found. This can include, for example, pathogens from raw meats getting into ready-to-eat foods like deli meats. It can also include nuts (which some people are very allergic to) getting into a food that does not normally have nuts (e.g., tomato sauce).

To prevent problems:

- Use separate cutting boards, separate cleaning cloths, knives/utensils, sinks, preparation areas, etc., for raw and for ready-to-eat foods. Otherwise, wash all of these items with detergent and sanitize them with bleach between use.

- Use separate storage areas for raw and ready-to-eat foods. Always store ready-to-eat foods on separate shelves and above raw foods. Store dry foods above wet foods.

- After handling raw foods, always wash your hands properly before doing anything else.

- Keep wiping or cleaning cloths in a container of fresh bleach solution (30 mL/1 oz. of bleach per 4 L/1 gal. of water) when not in use.

- Use clean utensils, not your hands, to handle cooked or ready-to-eat foods.

[h5p id=”59″]

The Major Types of Foodborne Illness

Foodborne illnesses are either infectious or toxic in nature. The difference depends on the agent that causes the condition. Microbes, such as bacteria, cause food infections, while toxins, such as the kind produced by molds, cause intoxication. Different diseases manifest in different ways, so signs and symptoms can vary with the source of contamination. However the illness occurs, the microbe or toxin enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract, and as a result, common symptoms include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain. Additional symptoms may include vomiting, dehydration, lightheadedness, and rapid heartbeat. More severe complications can include a high fever, diarrhea that lasts more than three days, prolonged vomiting, bloody stools, and signs of shock.

One of the biggest misconceptions about foodborne illness is that it is always triggered by the last meal that a person ate. However, it may take several days or more before the onset of symptoms. If you develop a foodborne illness, you should rest and drink plenty of fluids. Avoid antidiarrheal medications, because they could slow the elimination of the contaminant.

Food Infection

According to the CDC, more than 250 different foodborne diseases have been identified.[1] Majority of these diseases are food infections, which means they are caused from food contaminated by microorganisms, such as bacteria, by microscopic animals called parasites, or by viruses. The infection then grows inside the body and becomes the source of symptoms. Food infections can be sporadic and often are not reported to physicians. However, occasional outbreaks occur that put communities, states and provinces, or even entire nations at risk. For example, in 1994, an outbreak of the infection salmonellosis occurred in the United States due to contaminated ice cream. An estimated 224,000 people became ill. In 1988, contaminated clams resulted in an outbreak of hepatitis A in China, which affected about 300,000 people.[2]

The Reproduction of Microorganisms

Bacteria, one of the most common agents of food infection, are single-celled microorganisms that are too small to be seen with the human eye. Microbes live, die, and reproduce, and like all living creatures, they depend on certain conditions to survive and thrive. In order to reproduce within food, microorganisms require the following:

- Temperature. Between 40°F and 140°F, which is called the danger zone, bacteria grow rapidly.

- Time. More than two hours in the danger zone.

- Water. High moisture content is helpful. Fresh fruits and vegetables have the highest moisture content.

- Oxygen. Most microorganisms need oxygen to grow and multiply, but a few are anaerobic and do not.

- Acidity and pH Level. Foods that have a low level of acidity (or a high pH level) provide an ideal environment since most microorganisms grow best around pH 7.0 and not many will grow below pH 4.0. Examples of higher-pH foods include eggs, meat, seafood, milk, and corn. Examples of low-pH foods include citrus fruits, sauerkraut, tomatoes, and pineapples.

- Nutrient Content. Microorganisms need protein, starch, sugars, fats, and other compounds to grow. Typically high-protein foods are better for bacterial growth.

Food Intoxication

Other kinds of foodborne illness are food intoxications, which are caused by natural toxins or harmful chemicals. These and other unspecified agents are major contributors to episodes of acute gastroenteritis and other kinds of foodborne illness.[3] Like pathogens, toxins and chemicals can be introduced to food during cultivation, harvesting, processing, or distribution. Some toxins can lead to symptoms that are also common to food infection, such as abdominal cramping, while others can cause different kinds of symptoms and complications, some very severe. For example, mercury, which is sometimes found in fish, can cause neurological damage in infants and children. Exposure to cadmium can cause kidney damage, typically in elderly people.

Source: https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/chapter/the-major-types-of-foodborne-illness/

Good Manufacturing Practices

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) are written and implemented for a specific plant or food product as a prerequisite program for Preventative Controls for Human Foods. GMPs reduce the risk of hazards that could occur due to personnel and plant conditions.

Potential GMP categories include, but are not limited to:

- Building and Facilities

- Receiving

- Sanitation

- Food Handling and Processing

- Packaging

- Storage

- Personnel and Training

- Cleanliness

- Handwashing

- Jewelry

- Gloves

- Hair restraints

- No food in the processing area

Source:

https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/foodproductdevelopment/chapter/good-manufacturing-practices-gmps/

The following is an excerpt from the FDA given as an example of what a Good Manufacturing Practice document will look like:

| Sec. 117.95 Holding and distribution of human food by-products for use as animal food. |

| (a) Human food by-products held for distribution as animal food without additional manufacturing or processing by the human food processor, as identified in § 507.12 of this chapter, must be held under conditions that will protect against contamination, including the following:

(1) Containers and equipment used to convey or hold human food by-products for use as animal food before distribution must be designed, constructed of appropriate material, cleaned as necessary, and maintained to protect against the contamination of human food by-products for use as animal food; (2) Human food by-products for use as animal food held for distribution must be held in a way to protect against contamination from sources such as trash; and (3) During holding, human food by-products for use as animal food must be accurately identified. (b) Labeling that identifies the by-product by the common or usual name must be affixed to or accompany human food by-products for use as animal food when distributed. (c) Shipping containers (e.g., totes, drums, and tubs) and bulk vehicles used to distribute human food by-products for use as animal food must be examined prior to use to protect against contamination of the human food by-products for use as animal food from the container or vehicle when the facility is responsible for transporting the human food by-products for use as animal food itself or arranges with a third party to transport the human food by-products for use as animal food. [80 FR 56337, Sept. 17, 2015] |

Source:

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=117&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:2.0.1.1.16.2, Accessed on August 14, 2022 under fair use.