Introducing UNHE505

The major task in UNHE505 is to design and prototype a learning sequence, for a group of students that you teach, which includes the use of technology for learning.

By asking you to do this, and by encouraging you to document each step of the process and support your design decisions with scholarly sources, we hope to build your skills in selecting and using technology in your teaching. While you will focus on a challenge that is important to you, you will also have the opportunity to learn from the interests and investigations of the class.

We want to challenge you to learn more about the scholarship of technology-enhanced learning (“SoTEL”), and how it might inform and shape the way you teach in blended and online classes. Here are some of the questions that SoTEL should be able to help us answer in this unit:

- What research has been done on how technology enhances learning? (and does it?)

- Are there some disciplines and areas of study where technology-aided learning is more useful?

- What ideas are important in SoTEL? How do conceptual frameworks in TEL relate to debates in teaching, knowledge creation, citizenship, and society as a whole?

You will likely have other questions of your own.

The approach of this unit

This unit is somewhat different in its approach from your previous studies in the Graduate Certificate in Higher Education, as, alongside your scholarly work, you will be learning how to use technology in order to make a working version (a prototype) of the sequence that you design.

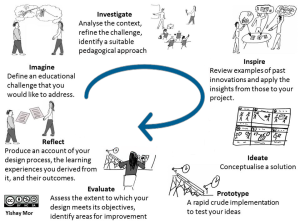

We have staged the steps in the design process by reference to the “design inquiry of learning” cycle. This cycle gives a structure to the decisions that we make as a teacher and designer for learning. In the assignments for UNHE505, we move around the cycle once. In a real teaching context, you might move backwards between steps and also go through the process several times to develop your teaching approach and sequence to your satisfaction.

Keep your sequence limited in focus

Start to think now about what topic or outcome your sequence might target, and the teaching challenge that you would like to address using technology in service of the learning and/or teaching.

Remember to keep the scope of your project work small – the sequence you design might be for just one or two weeks of a unit, or an integrated set of materials on a single concept or subtopic in your discipline.

Learn from class colleagues

As mentioned above, you will select your own path of interest for your own teaching goals, but you will also learn from class colleagues as they work through their own challenges. The activities in the unit often ask you to share components of your design with the class, and give and get feedback. You can take this work into your assignments, as interrelated components of a design portfolio.

There is lots to learn from the literature and from your peers, as well as from your students and your own reflective practice. I hope that, like past participants in this unit, you find much that is new, challenging and fascinating in this ever-changing field.

Goals for this stage

Suggested tasks at the start of the unit:

- Consider: can teaching work be seen as design work?

- Become familiar with ways to analyse a learning sequence and identify the functions of technological tools.

- Make pages for your design portfolio.

What are the connections between learning, teaching and design?

Consider your own work: can you see yourself as a designer as well as a teacher? Read the extract below about teaching as design, and think about ways that online learning requires a designer.

Reading 1, ‘Teaching as design’

The excerpts below have been selected from the article:

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching as design. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2, 27–50.

You can connect this work with the teaching activities noted in:

- the ACU Teaching standards and criteria framework (“Criterion 1: Design and planning of learning activities”), and

- the UK’s Professional Standards Framework (“Area of activity A1: Design and plan learning activities and/or programmes of study”)

1. Teaching as design for learning: An overview of the argument

Broadly speaking, teaching work in higher education is of three kinds. There is ‘interactive teaching’— when teachers and students are working together in real time. This is usually preceded by some kind of teacher planning activity and it is often followed by evaluative and reflective activity (Clark & Peterson, 1986, Moallem, 1998, Hativa and Goodyear, 2002). The evaluative and reflective teaching activity has twin foci. The teacher prepares feedback for students, e.g. through reading, marking and commenting on assignments the students have submitted. The teacher also reflects on the whole teaching and learning episode, and notes what they might do better next time. Ideally, the three phases form a loop, and the teacher’s work thereby takes on a self-improving dynamic.

This paper explores the argument that teaching in higher education needs to find ways of investing more heavily in the planning phase and that teachers’ planning needs to take on more of the qualities of design for learning. … Shifting resources towards design for learning, and adopting more effective design practices, is a credible strategy for improving the quality of higher education while managing with tighter funding. …

3. Teaching as design

Teaching as design is therefore part of pre-active teaching, and can be seen as a subset or type of planning—as planning that uses a distinctive mode of thought and set of tools and methods. However, design is probably most powerful when conceived as the intelligent centre of the whole teaching-learning lifecycle. For example, design can, and probably should, include (re-)designing evaluation instruments that are specifically tuned to picking up exactly the right kind of data to feed the next round of design decisions (Goodyear & Dimitriadis, 2013; Dimitriadis & Goodyear, 2013).

In relation to teaching as design, there are three main classes of things which can be designed:

(i) good learning tasks,

(ii) properly supportive physical and digital environments, and

(iii) forms of social organisation and divisions of labour. …

Two final points should be made about this design activity: (i) it works indirectly—students adapt, interpret and customise, (ii) it rarely involves the creation of brand new things—more often, it involves selections of existing things and their configuration into new assemblages. (Which is also true of design in other fields.)

[Figure 1 (adapted from Goodyear & Ellis, 2008)] helps pin down the essence of this view of teaching as design. It portrays design as having an indirect effect on student learning activity, working through the specification of worthwhile tasks (epistemic structures), the recommendation of appropriate tools, artefacts and other physical resources (structures of place), and recommendation of divisions of labour etc. (social structures).

These designed elements of a teaching event, the “things which can be designed”, have been identified by Goodyear and his students in many other settings, including online / technology-enhanced or “networked” learning:

| Design elements | which you could also think of as |

| Epistemic design = “worthwhile tasks” | (what) the play that is being staged |

| Social design = “social structures” | (who) the actors in the play |

| Set design = “tools, artefacts, physical and digital resources; the learning environment” | (where) the stage and all the props, and the script |

The elements identify the basic architecture of a learning sequence. Each of these components needs to be selected to facilitate the learner’s activities.

Taking it further …

Beyond the Lectern is a series of podcasts on the hot topics of higher education. Jason Lodge and colleagues interview some of the best teachers and researchers (at the time of writing, Duncan was the most recent expert!).

We recommend listening to episode 3, where Jason Lodge and Mollie Dollinger interview Peter Goodyear on what he really means by describing teachers as designers. He explains that, as well as being a habit of thinking about their teaching work, design also involves incorporating or making visible the tacit knowledge and experience that teachers have, their intuitions and their inspirations.

Ways to analyse technology-enhanced learning sequences

Identifying the designed elements: The design cycle (above) includes an ‘inspiration’ stage, where you can improve your own design by analysing the learning designs of other teachers. In Assignment 1 we ask you to analyse an article or case study of a technology-enhanced learning tool in use, and part of the analysis is to identify each of Goodyear’s “designed elements”.

Take an example where a learner is in a class where they are expected to develop their professional reflective practice. The learning sequence might include items which could be identified as follows:

| Design elements | Case study elements |

| Epistemic design (tasks) | The student might be set the task of “writing a weekly reflection” |

| Social design | which they are to do individually, with an audience of themself and their teacher, |

| Set design (physical and digital resources) | using a private blogging tool |

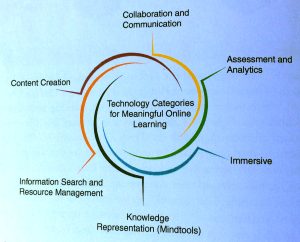

Categorising the technology’s function: As teacher-designers, we have a choice of what task to allocate and how to arrange the classroom or online space in social terms, and a choice of the kinds of tools and resources, both digital and physical, that we make use of to support learning. Technological tools can be classified in several different ways, but a categorization that is used in one of this unit’s recommended texts is as follows:

In this categorisation, the private blogging tool in the sample case study above would be classified as a collaboration and communication tool.

Reading 2, Categories of TEL tools

Reading 2, Categories of TEL tools

You can read about these categories in Chapter 4, ‘Technologies to support meaningful online learning’ (Dabbagh, Marra & Howland, 2019, pp. 49-75).

Use the summary tables in this chapter to see examples of tools in each category.

Setting up a space for your design work

As you are starting to consider what challenge you might develop a learning sequence for, we suggest that you set up a place to collect resources and present your design. We recommend the use of LEO Portfolio for this purpose, but you may want to negotiate the use of another online space or tool: please let us know, if so.

Instructions and examples of creating and sharing portfolio pages can be found in the LEO site, in ‘Analysing an educational challenge‘.

Sources:

Dabbagh, N., Marra, R., & Howland, J. (2019). Meaningful online learning : Integrating strategies, activities, and learning technologies for effective designs. New York, Routledge. Available as an ebook in ACU Library via Ebsco.

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching as design. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2, 27–50.

Mor, Y., & Mogilevsky, O. (2013). The learning design studio: Collaborative design inquiry as teachers’ professional development. Research in Learning Technology, 21(1), 1-15.

Further reading

(Further readings for this unit are always optional and often challenging.)

Goodyear, P. & Carvalho, L. (2013), The analysis of complex learning environments. Chapter 3 (pp.129-157) of Beetham, H. & Sharpe, R. (Eds.), Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: designing for 21st century learning, Routledge.

— this chapter has a lot crammed into it but pages 135 to 139 give some of the theoretical discussion behind the terms used in the summary activity (Assignment 1) for analysing a technology-enhanced learning example.