31

What is an “adaptation”?

Answer: A pre-existing work, often literary or theatrical, that has been made into a film. More commercial properties such as musical theatre, best-selling fiction and non-fiction, comic books, and so on, are also regularly adapted for the cinema. Adaptations of well-known literary and theatrical texts were common in the silent era (see silent cinema; costume drama; epic film; history film) and have been a staple of virtually all national cinemas through the 20th and 21st centuries. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels have been adapted in a range of national contexts but probably the most adapted author is Shakespeare, whose plays have appeared in film form as a large-budget Hollywood musical (West Side Story (Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise, US, 1961)), a historical epic set in feudal Japan (Kumonosu-jo/Throne of Blood (Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1957)), a Bollywood musical (Angoor (Gulzar, India, 1982)), and children’s animation The Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, US, 1994)), to name but a few. Adaptations often sit within cycles associated with a particular time and place, as with the heritage film in Britain in the 1980s, or the cycle of Jane Austen adaptations in the late 1990s. It is claimed that adaptations account for up to 50 percent of all Hollywood films and are consistently rated amongst the highest-grossing at the box office, as aptly demonstrated by the commercial success of recent adaptations of the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling. A property ripe for adaptation is referred to as pre-sold; older works in particular are attractive to film producers because they are often out of copyright. Video game (Resident Evil (Paul W.S. Anderson, US, 2002)) and comic book/graphic novel (Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff, US, 2001)) adaptations are increasingly common and a certain level of self-reflexivity regarding the process of adaptation itself can be seen in films such as Adaptation (Spike Jonze, US, 2002).

Source: Kuhn, A., & Westwell, G. (2012). “Adaptation.” In A Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 27 Mar. 2017

The Essentials of Adaptation

Literature and film, movies and books, compare like apples and giraffes, said contemporary American writer Dennis Lehane. But they do compare. They do interbreed. As do history and film. But the question is: How and why do history, literature, and movies fruitfully nourish one another? When apples, giraffes, and other exotica interbreed what results?

Many thousands of movies are adaptations from historical or literary sources. Hence the recent internet vernacular of “litflicks”—literature adapted into flicks, the flickering medium of the motion pictures.

Although literature, history, and movies are distinct forms of communication thousands of solutions and accommodations have been found so they can get along and have fruitful relationships. The first key is the nature and tradition of adaptation itself. Tales evolve and one generation adjusts the stories of the past to the present time and to its modern needs and ways of storytelling. “My dramas are but slices cut off from the great banquet of Homer’s poems,” wrote the Greek dramatist Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.E.). But Aeschylus’ dramas were leaner and meaner, in search of a higher truth which synthesized moral opposites, profoundly simpler than anything all-embracing Homer ever wrote. For it is the singer, not the song, that makes the splendor of communication successful. And a story retold, as Aeschylus retold Homer, continues. What is beneath the surface of the story that has been told before and will be told again—a story that has been alive among humans for centuries or millennia?

Consider how information exists and knowledge is distilled. How a story is told is as important as its subject matter. Thus, three fundamental points about how the nature of literature and history effect their relation to movies:

First, legend precedes historical fact. Did Nestor and Ajax in the Iliad ever actually exist and do what Homer claims they did? Until factual, textual proof is found this remains, at the least, an open question. The Iliad remains legend rather than history, literature rather than history, superstition rather than science. Hence, human culture as we know it shows that literature precedes history as a practice of inquiry, as a creative record of human events.

Second, a fundamental distinction exists between history and memory. History is then, memory is now. A judicious, critical management of documentary evidence allows history to get as close as possible to the facts of the past; then as it was then. Memory is the past remembered and reconstructed through the lens of the present and its building blocks.5 Movies flourish in a popular, contemporary marketplace. They must entertain the sensibilities of the present. Anachronism is their delight and pleasure. Memory is their very breath. So history inevitably gets short-changed in movies—with some notable exceptions.

Third, with regard to the history of ideas, one distinguishes between an older meaning of literature as literacy and the cultivation of reading (dominant through the eighteenth century) and a newer reality and reference to literature as a body of writing which contrasts with erudition and which emphasizes wit, talent, and taste (which begins to dominate the older meaning by the end of the eighteenth century). Storytelling movies that are not straight documentary or raw, live footage have a much stronger generic affinity to literature than to history. Thus the movie-history relation is more a connection rather than a similarity, an association rather than nearness. The difference is subtle but meaningful. The viewer can expect a movie to be like literature. But can you expect a movie to be history?

Literature and Film as Culture

Culture is not handed on like a baton in a relay race from one generation to another or from one nation to another. As it evolves, culture has to be reproduced. “A culture does not have an independent inertia.” In classical terms, cultural history is a secular humanist, Aristotelian approach to culture. My a priori assumption is that all knowledge is gained and perpetuated by the close association between the human mind, spirit, and body conditioned by the environment of its time. No Greater Power—from archetypes to Godhead, to Platonic “forms”—exists independently of our sensible world, of our human need to construct, guide, give and get what we require as human beings. Man is his own maker.

The ancient art and craft of adaptive communication means recreation. Beneath the surface of a story refurbished over the ages and updated by different media lies a heritage of useful knowledge which adds to well-being in proportion as it is communicated. The genesis of the forms themselves can now help us to figure out the relationship of literature to film, the written word to the visual image.

Converting Words to Images Using Technology

One last point about the material and conceptual nature of literature, history, and movies. Literature and history must have the word—logos. Their particular nature as media consists “precisely in the abstractness of language, which calls every object by the collective name of its species and therefore defines it in only a generic way, without reaching the object itself in its individual concreteness . . ., hence the spiritual quality of its vision, the acuteness, and succinctness of its descriptions.” As literature and history advance beyond their oral stage, they demand the written word (or print) conveyed by reading. The medium of movies needs images in motion which are conveyed by a projection onto a screen. In all works of art, there is a hierarchy of media. For movies the image, iconos, dominates.

A movie gets to places literature and history do not. And then it delivers that place to its audience in a way literature and history cannot. The audience, in turn, must use their eyes for a movie to work. After all, are not literature and history forms of communication which are more available to a blind person? With literature and history the audience sees with their inner eye, not as much with their outer, physical eye. “Film creates a fully defined and immediate physical reality that requires dramatization and exploration; it brings characters visually realized into direct relationship with their environment and in immediate proximity to the viewer.”

Cinema also needs electricity. Movies could never have existed without the necessary technology. Print advanced literature beyond the spoken word and the written page and allowed mass media. But technology midwifed movies into their very existence. Technological determinism has played a much greater part in the creation of movies. From its modern inception, the technology also helps to distinguish the entertainment film from the documentary. In 1893 the American inventor and businessman Thomas Edison created the first film company to make and show movies to the public. The Edison Company filmed in a tar paper barn set on a swivel, in which the roof could be opened or closed so as to adjust to the sun. Edison’s unwieldy camera, the Kinetograph, was a large, fixed machine run by an electric motor to ensure smooth motion. The point here is that Edison’s “camera did not go out to examine the world; instead, items of the world were brought to it—to perform. Thus Edison began with a vaudeville parade: dancers, jugglers, contortionists, magicians, strong men, boxers, cowboy rope twirlers.”

Types of Adaptation

For almost as long as film has been an art form, books have been adapted for film. In fact, the earliest known motion picture based on a literary source was filmed in 1896. (It’s a 45-second scene from George DuMaurier’s 1894 novel Trilby.)

And for just as long we’ve adapted books for the screen, we have also discussed the question: What makes a good adaptation? Which matters more: the quality of the film itself, or how “accurate” it is to the book it’s based on?

Of course, there is some complexity, even difficulty, to these questions. Novels and films are different art forms. To expect a 90-minute film, or even a longer TV series, to be an exact rendering of every detail of a book is a bit unreasonable. Novels also use many devices that are just impossible—or at least extremely difficult—to film. So filmmakers have to get creative, which is when it gets interesting.

The Literal Adaptation (a.k.a. “Museum”)

The Literal Adaptation (a.k.a. “Museum”)

A strong expression of a literal adaptation is often a play performed as a movie. A historical museum exists to preserve and protect historical artifacts and records; to alter them in any way is considered taboo. A museum is also concerned with placing artifacts and records within their historical context, through interpretive signage and other materials. In the same way, a “Museum” Adaptation is concerned with preserving every possible detail of the book exactly how it exists in the book, just transferred to the film medium.

Example: Pride & Prejudice (1995)

If there was ever a perfect example of a Museum Adaptation, it is the 1995 TV miniseries of Pride & Prejudice. This version includes nearly every scene from the book, however brief or fleetingly mentioned and even some scenes that are NOT in the book. Everything is perfectly preserved and nice to look at, but we are not allowed to touch. For many fans, this near-perfect preservation makes this adaptation their favorite.

The Faithful Adaptation (a.k.a. Artistic)

The Faithful Adaptation (a.k.a. Artistic)

The faithful adaptation takes the literary or historical experience and tries to translate it as close as possible into the film experience. Sometimes there are equivalents in film to the original way of saying or doing what happens in literature and history, and sometimes not. And “faithful” depends on the movie makers’ knack to be true to the original spirit of the raw stuff, the primary source. Faithful works from the inside out; loose works from the outside in. Loose has no problem with dismantling and reassembling, breaking up and remaking totally anew. Faithful wants to stay loyal to the intention of the original, to convey the heart and soul. So in a faithful adaptation, even if the movie went so far as to change the original story’s ending, the movie makers would want to make sure that they did not betray the core meaning.

This type of adaptation is most concerned with finding a balance between being true to its source material, and creating a film that can stand on its own as a work of art. Its a sort of a conversation between the book and the audience. Rather than preserving every detail like a museum, an Artistic Adaptation finds the essential elements of the book and interprets them in ways that are meaningful for the audience.

Example: Pride & Prejudice (2005)

The more artful elements are part of what turned a lot of Austen purists off to the 2005 adaptation of Pride & Prejudice. Its aesthetic is grittier but warmer than the 1995 version. Its set and costume design are less concerned with historical accuracy than with reflecting the characters’ personalities and relationships. It also by necessity cuts or combines plot points from the novel to fit within its two-hour runtime. This is definitely an artful film, and the most essential elements of the book are all present and imbued with meaning for modern audiences.

The Loose Adaptation

The Loose Adaptation

The loose adaptation takes the raw stuff and reweaves it into a movie as the director, producer, or studio wishes and as the movie needs. Contemporary cultural norms are often a determining factor. We’ve all seen a movie that we would call a “Loose Adaptation,” a film that keeps a few elements or some semblance of the premise of the book it’s based on, but then more or less does its own thing with them. We often discuss this type of adaptation in negative terms, as if its lack of exact similarity to its source material is somehow a failing. And for many people, it is. But a Loose Adaptation can still be a really good movie.

Example: Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Nineteen-forty was an interesting time, and in many ways, the adaptation of Pride & Prejudice from that year is typical for the time. The story is sort of there, but the film rearranges or omits plot points seemingly haphazardly, and adds arguably unnecessary scenes. The costumes are decidedly more Victorian than Regency. Characters’ personalities have even changed, most noticeably Lady Catherine’s. But despite all that, this version is actually an enjoyable movie.

The Transformative Adaptation

The Transformative Adaptation

We most often see Transformative Adaptations of well-known classic works from the English literary canon. Works by Shakespeare, Austen, and Dickens, as well as fairytales like “Cinderella,” are common Transformative Adaptations. These films set their source works in a time period other than that in which they were written, often in the contemporary era. They may also take place in a different culture from the source work, or in a subculture of modern Western culture.

Through changing the setting, Transformative Adaptations seek to accentuate the timelessness and universality of their source works’ messages and themes. They can also be useful for commenting on the traditional whiteness and heteronormativity of literary canon. And while setting a Shakespeare adaptation in a non-European culture and casting actors of color should never serve as a replacement for elevating actual works from that culture, it can serve as a bridge.

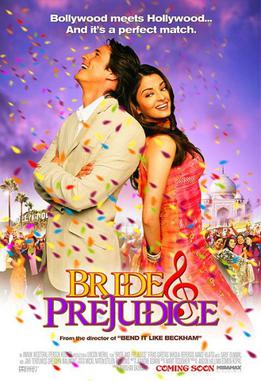

Examples: Bride & Prejudice (2004)

Austen works in general, and Pride & Prejudice in particular, probably have the most Transformative Adaptations of any author or work. Bride & Prejudice sets the story in modern India, Britain, and the U.S., turning Elizabeth and Darcy’s class differences from the original novel into a clash of cultures, as well. It retains the essentials of the book, but introduces new significance to the themes through viewing them with fresh eyes.

The Cinematic Process

First, the filmmaker has to locate a coherent story that an audience will accept and want to see told. Or, rather, re-told on screen. Shakespeare is always good fodder.

First, the filmmaker has to locate a coherent story that an audience will accept and want to see told. Or, rather, re-told on screen. Shakespeare is always good fodder.

Second, the producer has to figure out what the film will cost once it is adapted from this work of fiction and if he can pay for it. If the work is no longer copyrighted, all the better. Then there is no original intellectual property to worry about and no royalties to pay for a primary text. If it is an old story, the primary text might also be attractive because it is a costume drama—such as an adaptation from Charles Dickens or Henry James.

Third comes the matter of precedent. Has this kind of thing sold before? Since movies are a commercial industry—like cars, pencils, or the production of different brands and flavors of toothpaste, well, you figure it out—the bank wants to back merchandise with a good track record. If one brand of toothpaste hits upon peppermint as a smash hit with the consumer, then many other peppermint-flavored brands will soon follow. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “If a man can write a better book, preach a better sermon, or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, though he builds his house in the woods, the world will make a beaten path to his door.”

One should see movies not only as fulfilling the requirements of a genre, but as part of a cycle, as film critic Jonathan Muby has insisted. A “cycle” was the term commonly used in America for movie types prior to World War II. This is where censorship—which has affected both literature and movies in America—enters in. Both violence and gangsterism in literature and movies can be socially threatening. They are dangerous expressions “of a larger disorganizing and destructive force,” cycles of violence and crime which threaten society. Especially when displayed in the mass media of movies they threaten society from within—they are cycles “vocalized from within the machinery of cultural administration.”

The fourth step in the modern creative process of film-making is the pre-sale. In the movie industry, pre-sale has two meanings. Before you sell your commodity to the general public, you conduct a private sale of the product. This way one gains financial support to complete the product and may provide eventual profits for the investor. And as pre-sale is the formative period before sale, product production may be distant from the actual place of production and initial distribution. The maker can sell a product not yet produced in one country in yet another country far away. It is all part of the movie game. With a movie, one can have outstanding actors, special effects, and a great story in hand—from which basis one sells the distribution rights prior to completion. Particularly abroad; overseas is a good place to sell. They buy on conceptual credit—Sherlock Holmes from the British for the Americans, Sylvester Stallone or Clint Eastwood from the Americans for the Europeans. If the final film is a bomb, the producer has made more money this way. If it is a blockbuster, everyone profits. Either way, the studio and the producer can enhance the initial production budget.

Fifth is a series of complications in the practical work of actually adapting fiction into film, the actual making of the movie, the production itself. This is a time and a place when words have to be juxtaposed with images. That is to say, when the original letter matters. But “fidelity to the original spirit of the piece is not always to the letter, because the letter does not necessarily work on film.” Actions have to be transferred from descriptions to dramatizations, from slow to snappy timing. Time strictly controls the adaptation possibilities—90 to 180 minutes for a film, which is much less time than it takes to read and digest most books. The written story may be richly textured, and minor incidents, settings, and characters have to be cut out, or down, or be consolidated. When a tale goes from fiction to film “shaping a story to be told with the minimum necessary number of scenes and characters and the most contained list of locations is a necessary part of the game.” Most people in professional, corporate life are now acquainted with this practice—the need to adapt to a concise, word and visual presentation. This happens when one goes from a free-flowing, person-to-audience presentation of information to a form-fitting, powerpoint presentation. One has to fit into the given frame. To accomplish this can be a straight jacket experience. Or it can condense and order one’s efforts like the composition of a sonnet for the one you love.

Finally, the sixth concern in the practical work of adaptation is the audience—or, as the American lyricist, musical comedy, author, and theatrical producer Oscar Hammerstein II reportedly called them: “That big black giant.” They are a devouring abyss that the producer ultimately cannot control and who finally decides if the creation works or not.

The whole collaborative and creative process of filmmaking itself shows us that adaptation is not one element transferred to another singular element. As with U.S. popular culture, the realistic paradigm is culture as a whole. Perhaps the fundamental issue is not zero to five stars, a series of qualitative rankings that range through poor, fair, good, better, and best. (Although, to be fair, excellence happens—as does its opposite.) But the fundamental issue is that “there is a totality of culture that pervades and surrounds a society rather than a culture that exists in tiers.” A story is told and retold.

![]()

Case Study:

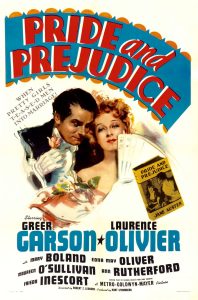

The Old Guard

Synopsis

From Variety:

‘The Old Guard’ Review: Gina Prince-Bythewood Delivers Netflix’s Best 2020 Action Movie

Charlize Theron stars in a comic-book movie with a point of view, creating a marriage of expectations and twists unlike little else in the genre.

By Kate Erbland, 3 July 2020

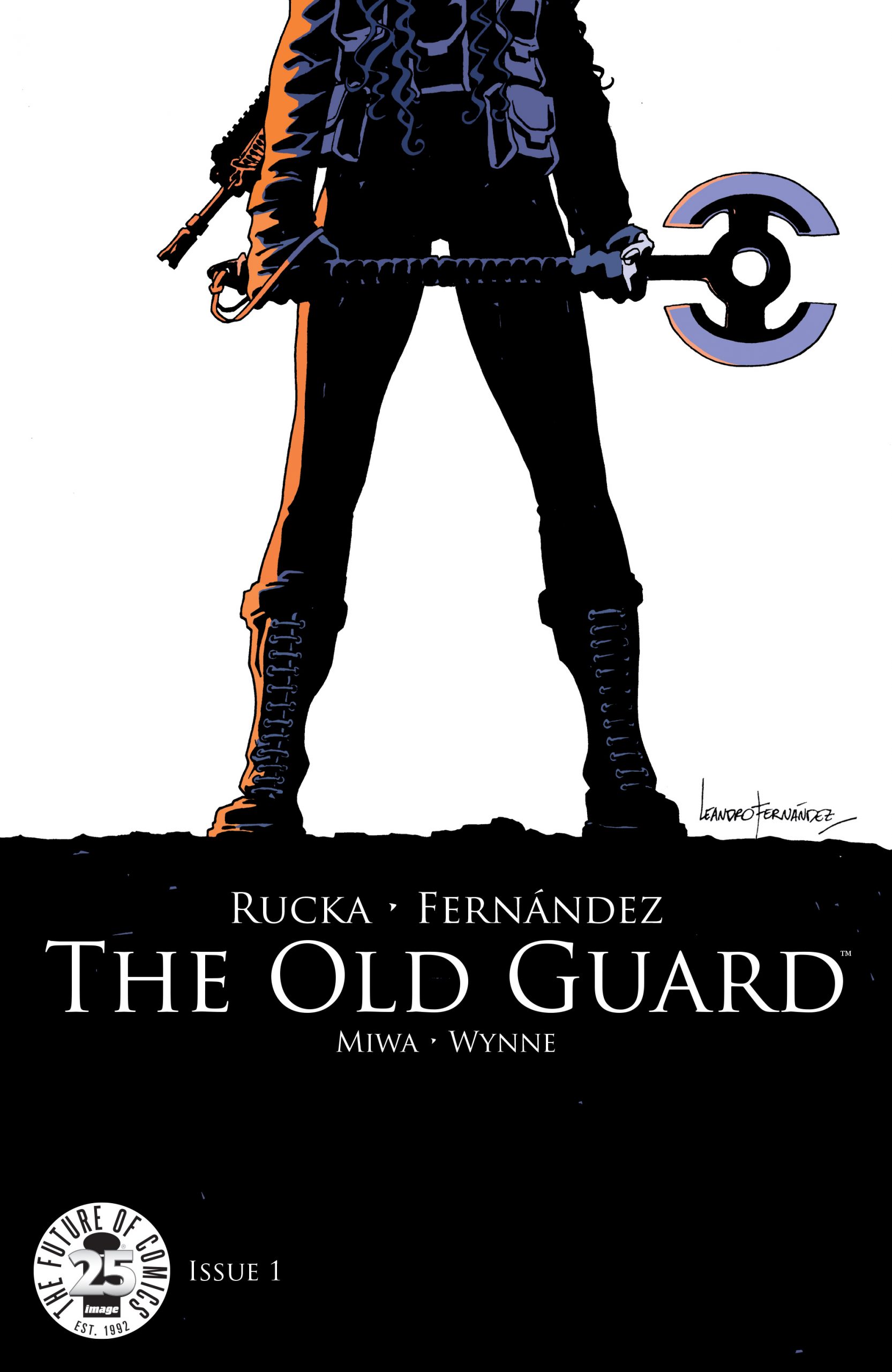

Being a superhero isn’t an easy gig, an idea that has inspired recent cinematic explorations ranging from the sublime (“Logan”) to the ridiculous (Tobey Maguire going goth in “Spider-Man 3”). That same concept also drives Gina Prince-Bythewood’s “The Old Guard,” a Netflix-produced take on Greg Rucka and Leandro Fernandez’s 2017 comic book miniseries of the same name, but her version is as fresh as any comic book movie made since superhero mania swept the multiplex.

Even the film’s own star Charlize Theron previously interrogated the weirdly relatable theme that being a superhero can be a real slog in Peter Berg’s “Hancock.” Here, she’s the oldest member of the Old Guard, kick-ass mercenaries who happen to be a) very old and b) mostly immortal. And as the film opens, she finds herself again pondering the value of fighting the seemingly same battles on an unending timeline. Despite the familiarity, “The Old Guard” manages to be both very grounded and very entertaining, a marriage of expectations and twists unlike little else the genre has inspired even during its most fruitful times.

Prince-Bythewood, while still best known for her singular romantic drama “Love & Basketball,” is no stranger to comic book work, having been long attached to direct “Silver and Black” (a Sony production meant to team up Spiderman stars Silver Sable and Black Cat) and even directing an episode of Marvel’s short-lived “Cloak & Dagger” series. But her greatest strength lies in her interest in complex people, making “The Old Guard” a perfect fit for her wide-ranging sensibilities. Oh, and the action. Did we mention the action? We will.

Still, Prince-Bythewood is not entirely free of the constraints of the genre and some of the film’s narrative trappings will not surprise, from an undercooked villain and a winking conclusion that just barely subverts the standard post-credits reveal (this time, the twists are before the credits!). But the film (and particularly Rucka’s script) leave plenty on the table for further incarnations, making it another rarity: a comic book movie that earns its franchise potential.

Andy (aka Andromache of Scythia, if you’re feeling historical) has seen it all before, and Theron enters the film with a world-weariness that’s understandable even to beings that haven’t lived for thousands of years. “The Old Guard” opens as Andy makes tentative steps to return to her clan and their self-imposed duty to do good through all manner of holy ass-kicking. Their mantra is simple enough (do what they think is right) and while it’s kept them alive for hundreds upon hundreds of years, it doesn’t seem to be making much difference in the world itself. “The world isn’t getting any better, it’s getting worse,” one character spits, an observation that’s tough to fight, even removed from a world in which superheroes are possible.

Pulled back into the fray — and eager to reunite with the only other three beings like her (portrayed by Matthias Schoenaerts, Marwan Kenzari, and Luca Marinelli) — Andy and her team take on a mission to save a group of kidnapped schoolgirls in the South Sudan. The plan came from a new ally (a wonderfully understated Chiwetel Ejiofor) and when it all goes topside, the foursome must root out who sold them out, and why. And while that does sound familiar, that’s part of its sneaky power: Nothing the team has dealt with before is new (even if the film’s bad guy, played by Harry Melling, who doesn’t quite let his baddie get icky enough, thinks it is), and maybe nothing ever will be again.

And yet. Rucka’s screenplay works out a clever entry point that not only helps to explain some of the weirder aspects of their mythology (key: they’re not actually immortal, but close) and enlivens a narrative that is built on being sick of the same old shit. While Andy and her guys have known others like them — including Andy’s closest compatriot, played by Veronica Ngo in a series of emotional flashbacks — it’s been just the four of them for centuries now. Now caught in the drama of another big fight (against the world, the man, plain old hubris), they suddenly become aware of another member: Sprightly young Marine Nile Freeman (KiKi Layne) is understandably freaked out to discover that she can heal from even the most grievous of wounds. (And that’s to say nothing of the reaction of her beloved squad-mates.)

What the film ignores in terms of propulsive plotting — again, you likely know where this is going — introspection and intelligence more than make up for it. It’s a movie that wants its audience to think and if that sounds like a weird fit for the genre, you’ve surely never pondered what it would mean to be all-powerful in a world that only wants to see things go boom. That said, “The Old Guard” also takes the time to kick some serious ass. Andy and her pals have spent centuries trying to make the world better, but that has also required them to learn how to really fuck up someone along the way.

Through gritty, bruising action sequences and emotional flashbacks, the limits of their powers are revealed, as is the scariest bit: They can die, but they never know when it’s coming. Prince-Bythewood builds that fear into every single action sequence, among the best that Netflix has hosted in its growing body of action movies (and the very best of this year, which has already seen the release of the bone-crunching “Extraction”).

Steeped in hand-to-hand action (a sequence in which Theron and Layne go at it on a plane leaves a mark on them, the pilot, the audience, the guy walking around outside while you watch it inside your home, everyone), but with enough ballistic firepower to kit out a small civil war, every action sequence is more than awe-inspiring; they’re necessary to the film itself. Superhero battles that are eye-popping and narratively motivated? Oh, yeah.

It all builds to the revelation that perhaps Andy and her team’s attempts to aid the world have not been as fruitless as they’ve feared, and that doing the right thing (or even trying to do it) is worthwhile, even when it comes with a steep price. That idea adds heft to an already deep-thinking movie, and it also sets up plenty of ideas worth exploring in its inevitable sequel (which, yes, we can only hope will sport even more nutso action). Being a superhero isn’t easy, but “The Old Guard” reminds us that it — and the entertainment it can inspire — might be the best way to explore what it means to be a person.

Grade: B+

The Old Guard in Comics

The Old Guard on Film:

Netflix, 2020

Where to Watch: