7

The American Folklore Society describes folklore as “cultural DNA,” an apt metaphor. Folklore generally references the expressive arts, customs, and traditions shared by a culture or group of people.

The Greeks affectionately remarked that tales have no landlord. Like the “telephone game” children play, once a tale is delayed, it is open to revision and interpretation by all. The telling of tales has always been a political act, testing the reins of power, censorship, and authorship while simultaneously critiquing and informing societal culture. Whose voices are heard and whose are marginalized, appropriated, and/or parodied is a reflection of society. Folk tales depict the dichotomy of class and power as measured by status and wealth. Within both oral and written traditions, changes to patterns within the evolution of well-known stories reveal societal transformation. America’s preeminent folklore scholar acknowledged the collective value of tales:

“[W]e use fairy tales as markers to determine where we are in our journey. The fairy tale becomes a broad arena for presenting and representing our wishes and desires. It frequently takes the form of a mammoth discourse in which way we carry on struggles over family, sexuality, gender roles, rituals, and sociopolitical power.” -Jack Zipes, Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales

This chapter focuses on folktales: narratives or stories passed down from one generation of a culture to another through an oral tradition. Because folktales are imbued with the rituals, beliefs, lifestyles, priorities, and language of a culture, we can learn much about cultures past and present by reading them. Hence, folklorists (those who study folklore) are basically a type of anthropologist.

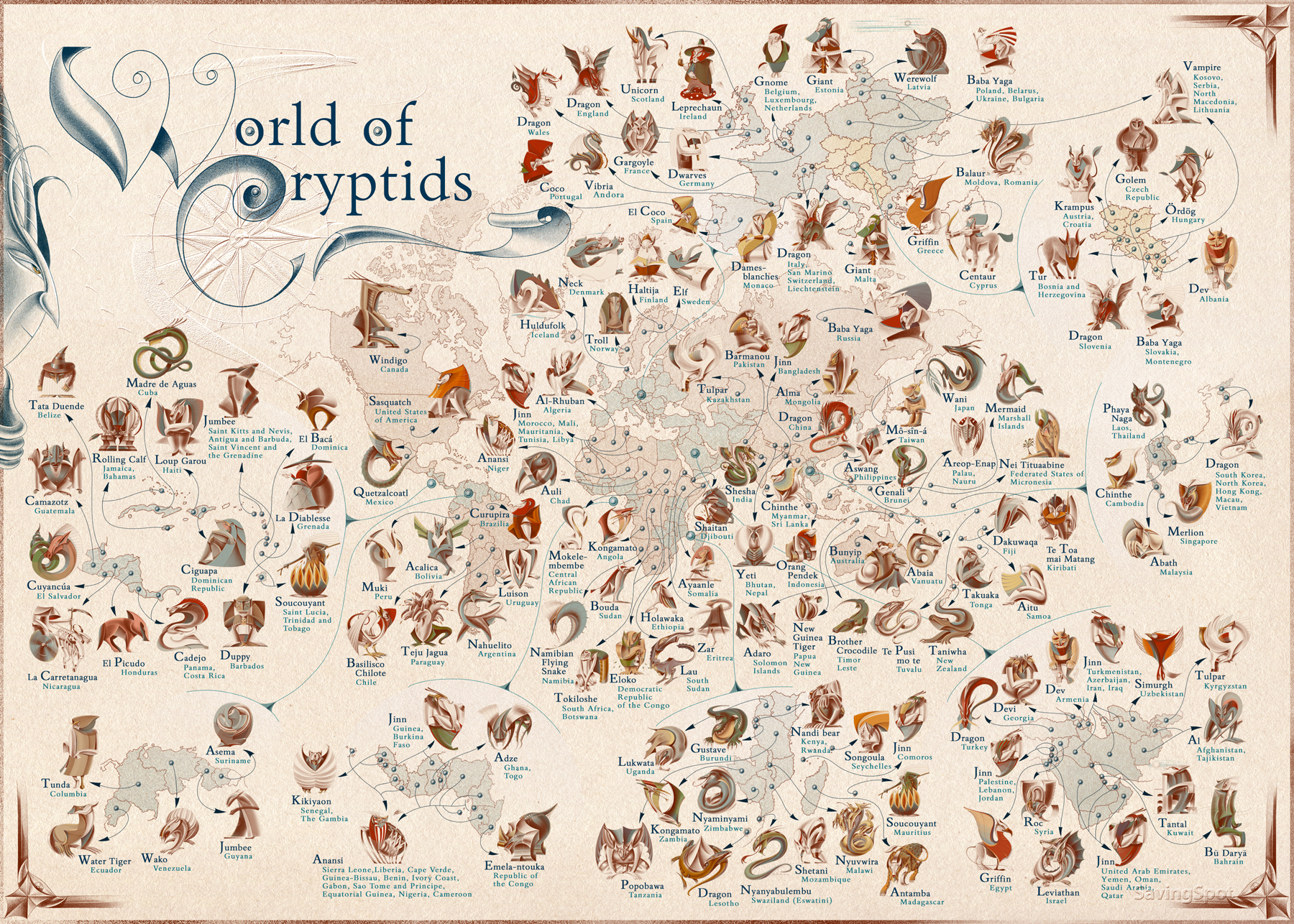

Folklore exists in every culture from every time and every place. However, individual stories change as they move from place to place or generation to generation. These changes created different versions of the same story. The ability to create and tell stories is unique to humans as a species, and it plays an important role in our growth and survival. Folktales are traditionally told orally, from generation to generation, until eventually (sometimes hundreds of years later), they are written down. Folklore represents certain aspects of a culture, such as its ethics and social classes.

Like mythology, fairy tales are a form of folklore. As such, we can learn much about a culture from studying their folk tales. Unlike mythology, though, fairy tales are not linked to any religious beliefs.

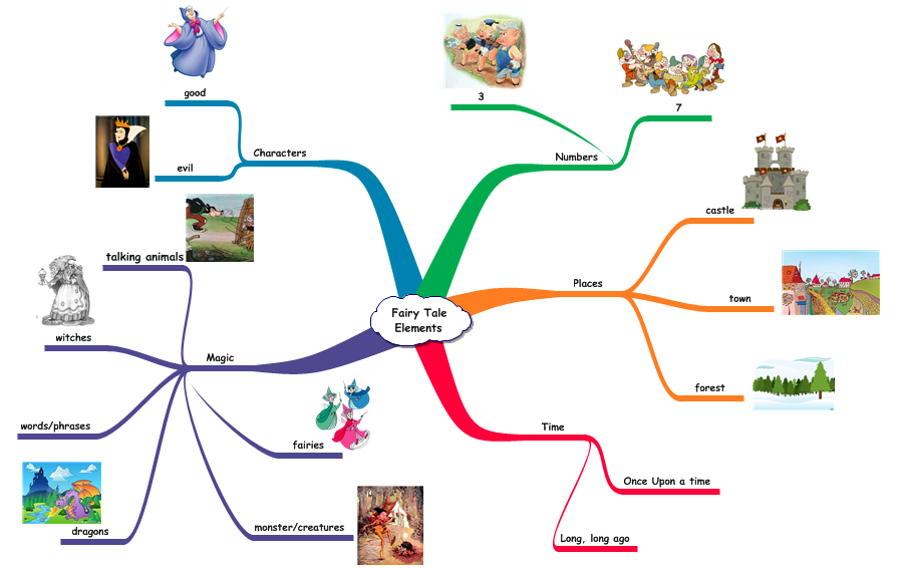

Elements of a Fairy Tale

All fairy tales contain the following three elements.

1. Supernatural or magic

All fairy tales contain supernatural elements, such as magic. They are not realistic, even they were originally based on real events. Often, the way such magic appears in a fairy tale is indigenous to the culture in which it originated. Magical creatures – from witches to wendigoes – are often created in a social consciousness through cultural expressions.

2. Good vs. Evil

Another element that all fairy tales share is the never-ending struggle between the forces of good and evil. This struggle is central to the tale’s conflict. It is through this conflict that the moral or lesson of the story is developed.

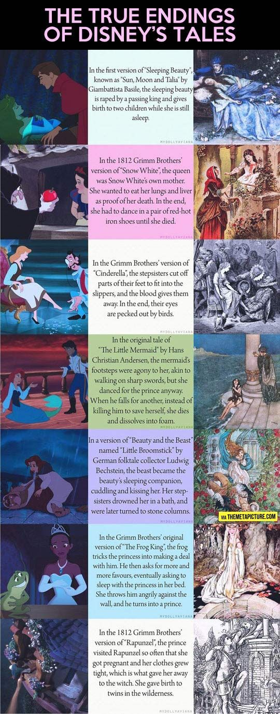

However, contrary to popular belief, the good side is not always victorious. The idea that fairy tales must have happy endings is a recent one, which gained traction in the 20th century, thanks in part to the media of Walt Disney. Previously, fairy tales were just as likely to have sad endings as happy ones. Modern readers are often disappointed with these original tales and their sometimes morose endings.

3. Hero

Representing the good side is often a hero. On the contrary, the evil side is not always represented by an entity. Sometimes it is a force, whether one controlled by nature, by man, or by the gods. While both sides have equal and opposite forces, a hero does not always face a villain. Sometimes it is even an internal force that the hero must struggle against.

Another effect of the Disneyfication of fairy tales is that audiences now expect the hero’s journey to be “PG.” However, when they were circulating, fairy tales were not only for children. In the absence of televisions and video games, folklore satisfied adults’ needs for stories. As such, the fairy tales that were told and retold for adults contained content that would not be considered appropriate for today’s children. The Italian version of Sleeping Beauty (“Sole, Luna, e Talia [Sun, Moon, and Talia]” by Giambattista Basile) contains statutory rape, adultery, infanticide, and cannibalism.

Purpose

Most fairy tales are created and retold to fulfill one or more of the following purposes.

To Retell or Remember

Some fairy tales were originally invented to commemorate an event that a community experienced. Retelling these experiences became exaggerated over time into a fairy tale.

For example, the story of “Little Red Riding Hood” originally developed after a series of wolf attacks. Villages in the heavily forested, mountainous areas of Germany and Russia suffered the loss of their members (particularly children) as wolf packs became larger and bolder. As the wolf population became better controlled, these stories evolved into purely fictional, unrealistic accounts. As the centuries progressed, the victims of these attacks were forgotten, and the story “Little Red Riding Hood” changed, too. Instead of remembering real events, the lesson of the story became a warning to young women to beware of predatory men.

For example, the story of “Little Red Riding Hood” originally developed after a series of wolf attacks. Villages in the heavily forested, mountainous areas of Germany and Russia suffered the loss of their members (particularly children) as wolf packs became larger and bolder. As the wolf population became better controlled, these stories evolved into purely fictional, unrealistic accounts. As the centuries progressed, the victims of these attacks were forgotten, and the story “Little Red Riding Hood” changed, too. Instead of remembering real events, the lesson of the story became a warning to young women to beware of predatory men.

To Entertain

Especially before the advent of new media, fairy tales and other folk tales were a primary source of entertainment. Families and communities developed stories that were passed down from generation to generation. As people traveled more (usually for trade), they also traded stories. As such, the changes in time and place created new variations of these fairy tales.

Fairy tales such as “Snow White” were told to entertain. The suspense of Snow White’s fate, the appearance of the charming prince, and the evil queen’s punishment would have enthralled listeners over the centuries.

To Teach

While all fairy tales do provide a moral, some evolved primarily to teach a lesson. These types of fairy tales were not just for children, either. Tales such as “Jack and the Beanstalk” played this role.

Case Study: “La Belle et La Běte [The Beauty and the Beast]”

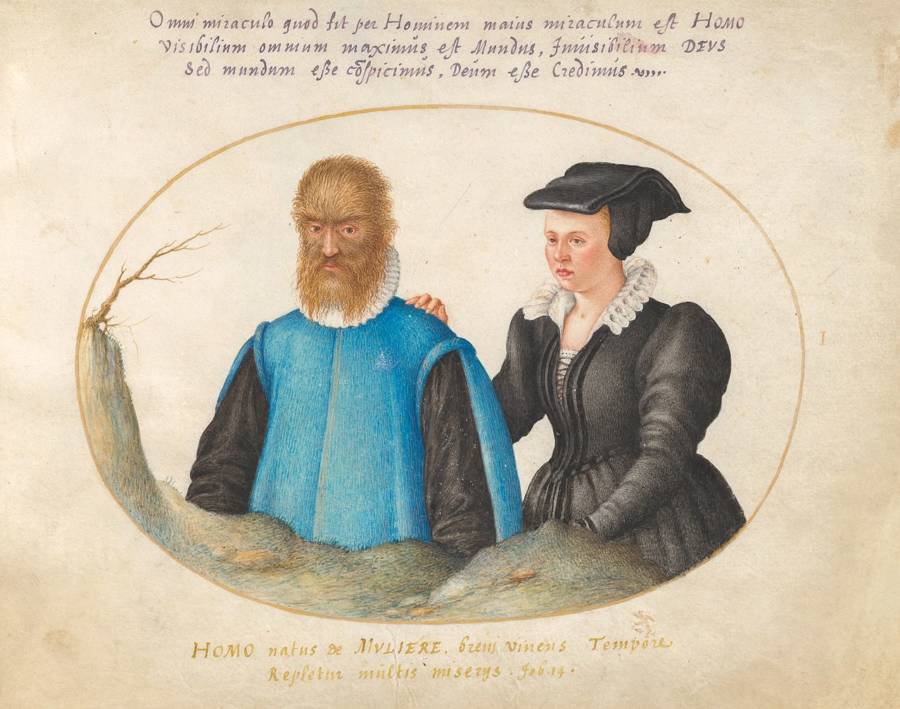

Like a lot of fairy tales, “The Beauty and the Beast” began as a true story. However, over time, magical elements were added, making it larger than life, and the real people who inspired it were forgotten. As the story changed, so did its purpose.

The real “beast” (though he never preferred to be called that) was a man named Petrus Gonsalvus, who was born in Tenerife in 1537. Gonsalvus was born with an extremely rare genetic disease called hypertrichosis, which caused extreme hair growth all over his body, except the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet. The hair growth is especially extreme on the face, ears, and shoulders, and the individual may have facial and dental deformities as well, adding to their so-called “beastly” appearance.

At the age of 10, Gonsalvus was taken from his home and sent to King Henry II of France in an iron cage as a gift, an addition to the king’s human menagerie. Likened to being a real-life wolf-man, Gonsalvus the “monster” was a monster hit amongst curious noblemen and women. People awaited the reputed “man of the woods” to bare his teeth and reveal his savage side. But that day never came.

Henry II discovered that Petrus Gonsalvus had a quiet and calm nature and decided that he would transform him into a true gentleman. In the royal court, Gonsalvus learned how to speak, read, and write in three languages, and his social station rose significantly. Henry II even awarded Gonsalvus a title and outfitted him like a nobleman of the court.

After King Henry II’s death, his wife, Catherine de’Medici, took on her husband’s “pet project.” She made it her mission to find Gonsalvus a wife. Acting as the Tinder of the 16 century, she kept Gonsalvus’ condition a secret. She was seeking a strong woman who wouldn’t be put off by someone unconventional. After a thorough search, Catherine settled on a woman who shared her name — Catherine.

One can only imagine this Catherine’s shock when she first met the suitor her queen had hand-picked for her, or Gonsalvus’ personal feelings about the match and the way the queen had purposely hidden his peculiarity. In any case, Catherine agreed to the match. Queen Catherine de’Medici was the most powerful – and the most dangerous – woman in Europe. She came from from a power-hungry family in Italy, famous for doing absolutely anything to attain more power, wealth, and land. Catherine de’Medici was rumored to be an expert in poison herself.

So, Lady Catherine wed Gonsalvus. It’s rumored that, at first, this arranged marriage was a bitter pill for the young beauty. Clearly, Catherine hadn’t been expecting a nobleman in a hairy wolf’s package. Yet in a series of events straight out of Beauty and the Beast, Catherine was eventually won over by her “beast’s” personality. The pair was married for 40 years and they produced seven children.

Unfortunately, Catherine de’Medici had her own ulterior motives for wanting Gonsalvus to marry.

Four of their seven children were born with hypertrichosis, the same condition their father had. Queen Catherine sent three of those children to other royal courts as gifts, a fate that mimicked Gonsalvus’ own, and kept the fourth in her own court. The children and their parents were heart-broken by the separation. In the French court at least, the children who were allowed to remain were well-educated and treated like nobles. In the end, Gonsalvus and his wife retired to a secluded estate in Italy, where they lived out the remainder of their lives.

Over the next 200 years, Petrus Gonsalvus would be all but forgotten, but the story “The Beauty and the Beast” remained. The story had become a source of entertainment with its magic curse and enchanted castle.

When Madame Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve published the story in novella form in 1740, her version had taken on a different role. Aimed at young ladies, it imparted some advice about marriage. At the time, all girls of noble birth were expected to marry a man chosen by their families. These marriages were arranged to benefit both families, which also had to be approved by the church and the king. Many girls barely knew their husbands before the wedding day. Love matches were rare. Noble women married for the first time at the average age of 16 (24 for men). Women married young so they would have more child-bearing years to produce an heir who would live to adulthood and carry on the family’s legacy. After all, infant mortality rates were high in those days. Therefore, a girl could expect her husband to be older than she was. Widowers (who mostly lost their wives to disease or childbirth) were expected to remarry and continue the process of producing heirs. That meant many of those 16-year-old brides were marrying men old enough to be their fathers.

Thus, Villeneuve’s message to young ladies was to not be disappointed by their husband’s outward appearance. Instead of a handsome and charming young prince, they may instead be married to someone much older and less attractive than they had dreamed of. However, Villeneuve’s story reminded young ladies to look to their husband’s better qualities. An older man, after all, was more likely to have learned the qualities of wisdom, patience, and conviction. Another woman, Madame Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, published an abridged version of Villeneuve’s story in 1757. Beaumont’s version was aimed at children and emphasized Beauty’s good manners and behavior in addition to her physical attractiveness.

Retellings of “The Beauty and the Beast” from the 20th century emphasized Beauty’s heroicism. It is one of the few stories from its time that featured the damsel doing the saving, rather than needing to be saved herself. For example, in Angela Carter’s “The Tiger’s Bride,” the heroine ultimately turns into a beast to join her lover, leaving her humanity behind, essentially turning Beaumont’s moral on its ear and celebrating women’s liberated sexuality in the latter half of the 20th century. In the 21st century, we have seen retellings (such as Alex Finn’s Beastly) that tell the story from the beast’s point of view.

In the end, Beauty and the Beast continues to be shared and retold to each new generation. New picture books, new novels, and new films appear on a regular basis, exploring the tale, some finding new meanings and subverting old ones while others cherish the original.

Classification

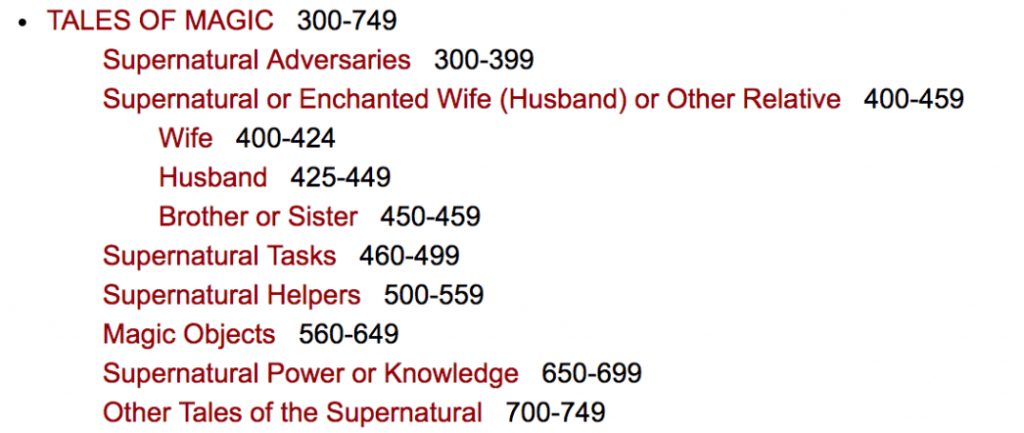

As mentioned earlier, as folk tales move from place to place and time to time, they evolve, creating different versions of the same story. To complicate matters, the same story may also develop different names in different languages. To better facilitate the study of these stories across languages, time periods, and cultures, we have assigned a series of numbers and letters to each individual story and its variations.

This is called the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) system, named after the three people who invented it: Antti Aarne, Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther. Aarne started the project in order to categorize Scandinavian tales and published his findings in 1910. Thompson translated it into English in 1928 and then revised and added tales in 1961, officially creating the AT or Aarne-Thompson system for cataloging folk stories. Uther stepped up in 2004 to further revise and update the system, and rename poorly titled categories. Uther called this new publication The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, which is another official title for the system.

For example, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther folklore classification system classifies Beauty and the Beast as “The Search for a Lost Husband” (ATU 425). ATU 425 is one of the largest classes in the system with few types containing more tales from around the world than this one. Jan Ojvind Swahn compiled a list of over 1,100 versions in his 1955 study. The Cupid and Psyche myth (recorded in Greece in the year 200 BCE) is one of the earliest tales in this class, often considered one of the first literary fairy tales. “Beauty and the Beast” fits into subtype ATU 425C, wherein the “lost” husband is found once the curse is broken. There are 11 other subtypes in the ATU 425, and anywhere from dozens to hundreds of recorded stories in each subtype.

The three numbers of the ATU system denote the major plot. The added letters further divide the stories based on motifs.

The most unusual ATU types:

ATU 34 – “The Wolf Dives into the Water for Reflected Cheese”

ATU 247 – “Every Mother Thinks Her Child Is the Most Beautiful”

ATU 322 – “Magnet Mountain Attracts Everything”

ATU 570 – “Bunnies Beware the King”

ATU 674 – “Incest Averted – Talking Animals”

ATU 678 – “The King Transfers his Soul to a Parrot”

ATU 1152 – “The Ogre Overawed by Displaying Objects”

ATU 1240 – “Man Sitting on Branch of Tree Cuts it Off”

ATU 1288 -“‘These are not my feet’”

ATU 1718 – “God Can’t Take a Joke”

Origins

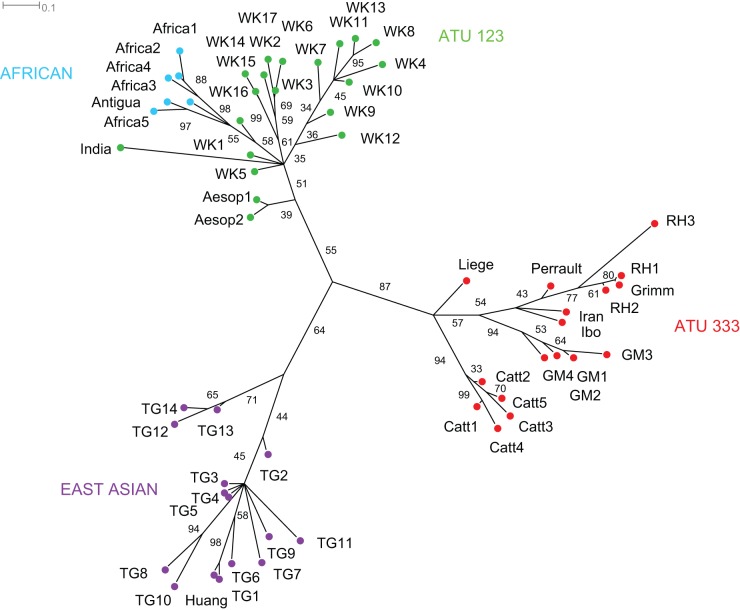

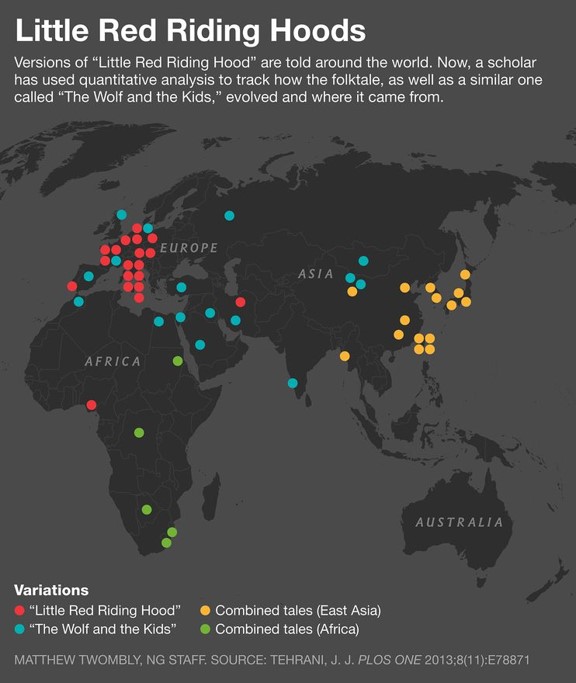

Once we know the different versions of a story that exist, we can start charting a story’s history and better identify its origins. Using analytical models that are typically used to study the relationships between species, Durham University anthropologist Jamie Tehrani created an evolutionary tree for “Little Red Riding Hood” and its cousins.

“Folktales are like biological species: They literally evolve by descent with modification. They get told and retold with slight alterations, and then that gets passed on to the next generation and gets altered again. In many ways the problem of reconstructing folklore tradition is very similar to the problem of reconstructing the evolutionary relationship of species. We have little evidence about the evolution of species because the fossil record is so patchy. Similarly, folktales are only very occasionally written down. We need to use some kind of method for reconstructing that history in the absence of physical evidence.” -Jamie Tehrani, “What Wide Origins You Have, Little Red Riding Hood!”

“Little Red Riding Hood” is labeled as ATU 333. It is believed that “Little Red Riding Hood” stories evolved from another type of story, “The Wolf and the Kids” (ATU 123), which were the first stories featuring a “big bad wolf” as the villain. Tehrani estimates that ATU 333 branched off from ATU 123 about 1,000 years ago. By looking at ATU 123 and 333 stories, Tehrani was able to chart Red Riding Hood’s family tree, showing how the story changed through time and place. Her study, “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood,” was published in PLOS One.

Folktale Collectors

Most of the fairy tales you have probably heard were likely collected by one of five people (pictured below).

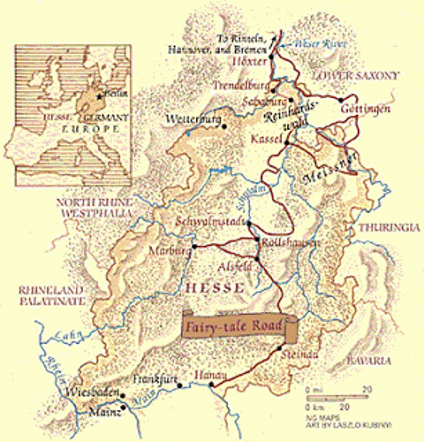

The world’s largest and most famous collection is that of the Brothers Grimm. They published what would become one of the most influential and famous collections of folklore in the world. Kinder und Hausmärchen [Children’s and Household Tales ] was first published in 1812, chronicling 86 stories. A second volume with more stories was published in 1815. The brothers continued collecting and editing their stories for the rest of their lives. The “final” version of their 210 stories was published in 1857. While many associate these fairy tales with other childhood stories, the Grimms, had curated the collection as an academic anthology for scholars of German culture, not as a collection of bedtime stories for young readers.

“Amid the political and social turbulence of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), as France conquered Germanic lands, Jacob and Wilhelm were driven by nationalism to highlight their homeland and heritage. They were inspired by German Romantic authors and philosophers who believed that the purest forms of culture, those that bonded a community, could be found in stories shared from generation to generation. Storytelling expressed the essence of German culture and recalled the spirit and basic values of its people. By excavating Germany’s oral traditions, the brothers urgently sought to ‘preserve them from vanishing . . . to be forever silent in the tumult of our times.’ -Isabel Hernandez, “Brothers Grimm fairy tales were never meant for kids”

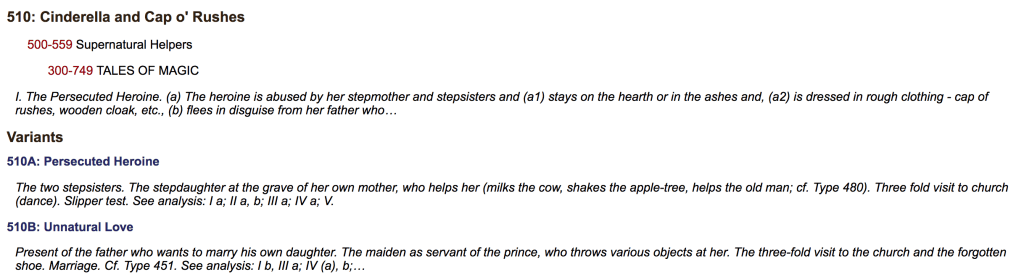

Cinderella (ATU 510A)

Type 510 tales are the oldest and most widely circulated “tales of transformation.” More specifically, “Cinderella” stories have more variants than any other ATU subtype. Over 1,000 versions of ATU 510A have been recorded.

Type 510 tales are the oldest and most widely circulated “tales of transformation.” More specifically, “Cinderella” stories have more variants than any other ATU subtype. Over 1,000 versions of ATU 510A have been recorded.

History of ATU 510A

The oldest version is “Rhodopis,” which hails from ancient Greece. The tale was first recorded by the Greek historian Strabo in the first century BCE and is generally considered to be loosely based upon a real person written about by Herodotus five hundred years before Strabo.

The first version of the story to gain popularity with its audiences is the Chinese version, “Ye Xian” (pronounced Yeh-Shen), which was told as early as 500 CE. It appears in Yu Yang Tsa Tsu (Miscellany of Forgotten Lore) written by Tuan Ch’êng-shih around 856-860 CE. The tone of the story implies that its readers and listeners were already well-acquainted with the story by the time it was written down. There is no fairy godmother in this earliest known version. A magical fish is Ye Xian’s helper instead. However, a golden shoe is used to identify Yeh-shen to the prince who wants to marry her.

The first version of the story to gain popularity with its audiences is the Chinese version, “Ye Xian” (pronounced Yeh-Shen), which was told as early as 500 CE. It appears in Yu Yang Tsa Tsu (Miscellany of Forgotten Lore) written by Tuan Ch’êng-shih around 856-860 CE. The tone of the story implies that its readers and listeners were already well-acquainted with the story by the time it was written down. There is no fairy godmother in this earliest known version. A magical fish is Ye Xian’s helper instead. However, a golden shoe is used to identify Yeh-shen to the prince who wants to marry her.

A discussion of Cinderella during the European Middle Ages and early Renaissance warrants a book of its own, for the stories are long, ranging from epics to ballads to legends of saints. The first modern European version is the Italian “Cenerentola,” recorded by Gaimbattista Basile in 1634. This version is notable for its murderous, conniving Cinderella, a far cry from the virtuous innocent we know so well. Despite the title’s implications, the book was not intended for a child audience but rather conveyed the “low class” or folkloric entertainment the tales emulated.

A discussion of Cinderella during the European Middle Ages and early Renaissance warrants a book of its own, for the stories are long, ranging from epics to ballads to legends of saints. The first modern European version is the Italian “Cenerentola,” recorded by Gaimbattista Basile in 1634. This version is notable for its murderous, conniving Cinderella, a far cry from the virtuous innocent we know so well. Despite the title’s implications, the book was not intended for a child audience but rather conveyed the “low class” or folkloric entertainment the tales emulated.

Inarguably, the most familiar Cinderella tale is the one published by Charles Perrault in his Histoires ou contes du temps passé in 1697. When most people think of Cinderella, a version of Perrault’s tale is the one they imagine. This is the version American audiences are most familiar with (i.e. the one used by Walt Disney and Rodgers & Hammerstein). Charles Perrault’s influence over the popularity of Cinderella cannot be overstated. His fairy godmother, pumpkin carriage, and glass slippers have inspired countless renditions of the tale in print, theatre, music, and art since its publication. While we can only conjecture about which oral and literary versions of Cinderella inspired Perrault, there is no doubt he left his literary stamp on the tale when he published it for the first time. Perrault, influenced by the French salons and the fairy tale writers of the late seventeenth century, added descriptive flourishes, romance, and humor to the story. While the events in his tale are not unique, Perrault most likely invented the glass slipper—there is no trace of it before his version—perhaps as an ironic device since it is a fragile thing and perhaps as simply genius creative license for it has become the iconic symbol of the fairy tale, even surpassing Perrault’s transformed pumpkin carriage as shorthand for the story. Perhaps the most regrettable element of Perrault’s Cinderella is her level of passivity. The known Cinderellas that preceded her were less passive, as are most of the lesser-known variants from all around Europe which postdate her. His Cinderella is rewarded for practicing goodness, obedience, and patience by primarily waiting to be rescued, often in tears. She does little else to help herself. Her character has served as a rallying point for modern audiences who want to label fairy tales as anti-feminist or teaching outdated values for women. And yet the majority rules, so Cinderella, in this iteration, remains the most popular when there are literally hundreds of others to choose instead. Perrault’s fairy godmother is also his own interpretation of the magic helper, not a unique invention, but another element dosed with his storytelling flair, one certainly rounded out by the French literary salons he frequented.

Germany is the country of the Brothers Grimm and their Kinder-und Hausmärchen, one of the best-known fairy tale collections in the world. While the influence of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm upon fairy tales and folklore is immeasurable, their Cinderellas are somewhat less familiar than those of Perrault. Their Aschenputtel is beloved by those familiar with it, perhaps as an antidote to Perrault’s version. Aschenputtel has a strong resemblance to other European versions from the region with a tree planted on her mother’s grave and doves that serve as the magical helpers who represent the deceased mother, instead of a fairy godmother. At the end, the stepsisters’ eyes are pecked by birds from the tree to punish them for their cruelty. Perrault’s version is considerably more forgiving than this version. Their version is really a composite of several similar tales they collected from tellers as well as literary sources.

Germany is the country of the Brothers Grimm and their Kinder-und Hausmärchen, one of the best-known fairy tale collections in the world. While the influence of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm upon fairy tales and folklore is immeasurable, their Cinderellas are somewhat less familiar than those of Perrault. Their Aschenputtel is beloved by those familiar with it, perhaps as an antidote to Perrault’s version. Aschenputtel has a strong resemblance to other European versions from the region with a tree planted on her mother’s grave and doves that serve as the magical helpers who represent the deceased mother, instead of a fairy godmother. At the end, the stepsisters’ eyes are pecked by birds from the tree to punish them for their cruelty. Perrault’s version is considerably more forgiving than this version. Their version is really a composite of several similar tales they collected from tellers as well as literary sources.

In 1893, the Folklore Society of Britain commissioned Marian Roalfe Cox to record all the “living” (currently circulating) Cinderella stories of the British Empire. The project, supposedly at Queen Victoria’s behest, was meant to highlight the variety of cultures living under British rule. At this point, Britain maintained territories, colonies, and commonwealths on all five continents; hence the saying “The sun never sets on the British Empire.” After four years of research, Cox had collected 345 variants, which she published (you can read the full book here). Over 150 years later, Swedish scholar Anna Birgitta Rooth repeated Cox’s study and collected over 700 variants. She published these as The Cinderella Cycle in 1951.

“While there is no official count of Cinderella tales—finding an exact number is virtually impossible—the general consensus is that well over 1,000 variants, with a conservative estimate of over twice that amount, have been recorded as part of literary folklore. In the past few decades, no scholar has apparently taken on the task of tallying them all, presumably due to the vastness of the project. In the end, more countries around the world have at least one, if not several Cinderellas, in their folklore than do not, whether it was created independently or borrowed from another culture.” -Heidi Anne Heiner, Cinderella Tales from Around the World

Classification of 510A

How did we get from the name “Cinderella” to 510A? The ATU system starts with seven broad categories that all tales are classified under:

- Animal Tales – 1-299

- Tales of Magic – 300-749

- Religious Tales – 750-849

- Realistic Tales – 850-999

- Tales of the Stupid Ogre (Giant, Devil) 1000-1199Anecdotes and Jokes – 1200-1999

- Formula Tales – 2000-2399

Like a lot of fairy tales, Cinderella fits in the “Tales of Magic” section. So, we can navigate to this section and see its contents.

In Cinderella, we have a magical helper in the form of a fairy godmother, so we now know we need to look in the 500-559 section. Scrolling through the 500s, we come across type 510: the persecuted heroine. That fits!

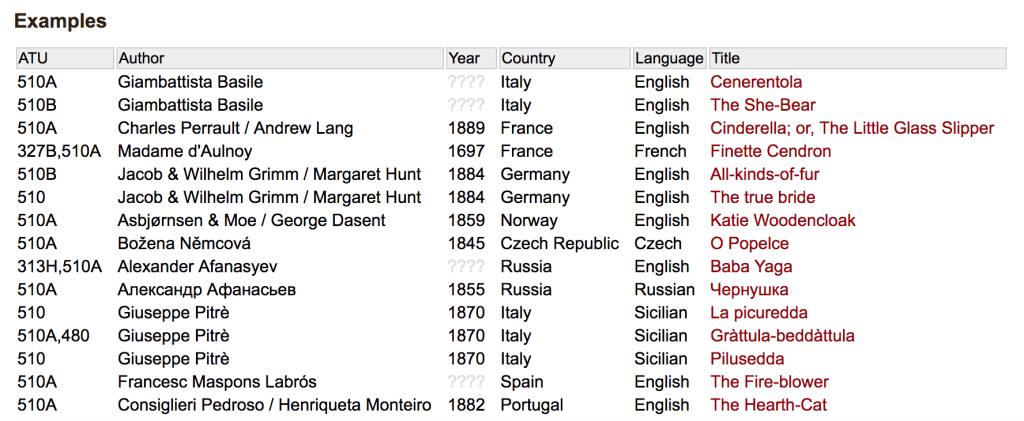

Like most types, ATU 510 has several subtypes. Cinderella fits into the first subtype (A), which features a motif of the “footwear test.” In the Multilingual Folk Tale Database, we can see a list of stories in this subtype. Unfortunately, due to the millions of tales in existence, they are not all listed in the database yet.

The tale always centers around a kind but persecuted heroine who suffers at the hands of her family after the death of her mother, except when her birth mother is one of her persecutors. Her father is either absent or neglectful, depending on the version. The heroine has a magical guardian who helps her triumph over her persecutors and achieve a wealthy marriage. The guardian is sometimes a representative of the heroine’s dead mother. Most of the tales include an epiphany sparked by an article of clothing (usually a shoe) that causes the heroine to be recognized for her true worth.

“Jack Zipes has a theory about why Cinderella has lasted as long as it has, no matter how often it’s edited or rewritten to express new moral lessons. He thinks it’s helping us think about a fundamental problem. ‘In our brains, there’s a place that we retain stories or narratives or things that are important to the survival of the human species,’ he says, ‘and these stories enable us to deal with conflicts that come up time and time again that have never been resolved.’

In Cinderella, Zipes says, the conflict is: ‘How do you mix families?’ Traditionally, the thing that makes Cinderella win — her beauty or her kindness or her cleverness — is the thing that the narrator points to as important for us to emulate in the moral of the story. But that attribute can be practically anything, and it won’t change the shape of the family story.

Zipes argues that this family story has always been enormously important. Depending on how you look at that repeated fairy tale narrative of jealousy and danger, Cinderella is either the classic Freudian family fable or it’s the story of women competing for male attention under a patriarchal system where they know they’ll need that attention to survive. Either way, it is an extremely durable story. We’ve been telling it over and over again for centuries.” -Constance Grady, “The slippery genius of the Cinderella story”

In his broad socio-historical study, August Nitschke traced Cinderella’s behavior and social activity in early variants to hunting and gathering cultures at the end of the Ice Age when women were central to the community. Cinderella’s mother often fulfills the role of the nurturer, appearing as a benevolent force of nature to help her daughter overcome obstacles. In his research, Nitschke wove together the origin of the tale with socio-historical contexts and the story’s narrative. He demonstrated that allegory reveals the evolution of society’s behavior – as society changes, so does the direction of the tale.

For example, modern women find the Cinderella character of some the more famous versions (like Charles Perrault’s) to be passive on an almost unbearable level. Even the Brothers Grimm continually edited the story to give their title character more direct discourse. However, before Perrault, Grimm, and the other famous fairy tale collectors came along, preserving and passing down traditions and knowledge was considered a woman’s responsibility to her family and community. These versions, entrusted to female storytellers, were actually more feminist than the ones later recorded by male collectors.

“Before the Grimms, these pioneering women were drawn to Cinderella not because they felt the story needed updating or revising, but because they were attracted by the culture that birthed it – a storytelling network created by and for women. At a time when only men could be writers or artists, women used folk tales as a means of expressing their creativity. Female labourers and housewives passed the stories onto one another to dispense shared wisdom, or else to break up the boredom of another working day as they toiled away from the prying eyes of men. Cinderella reflects these customs. It is a story about domestic labour, female violence and friendship, and the oppression of servitude. Perhaps most significantly, it is a story about female desire in a world where women were denied any role in society.” -Alexander Sergeant, “How Cinderella lost its original feminist edge in the hands of men”

Even after 12 centuries, tale type 510A continues to be passionately embraced around the world in endless versions and variations. Each wave of revision inspires fervent critique of the tale’s evolutionary trajectory. Regularly argued issues include archetypes, verisimilitude, gender, grief, magic, matriarchy, power, privilege, psychology, sociology, spirituality, sexuality, and consumerism. Such debate undeniably demonstrates the complex qualities of 510A across disciplines.

Questions:

- What can we learn from different cultures by studying their fairy tales? What can we learn from fairy tales that we cannot learn from other types of folklore, such as mythology?

- How were “original” fairy tales different from the ones we know today? What caused the way we think about fairy tales to change?