32

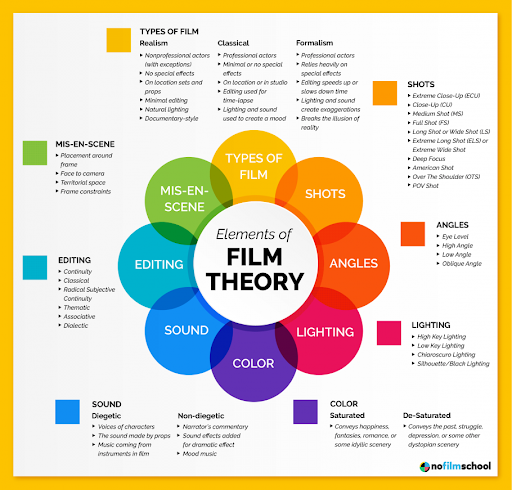

Writing a film analysis requires you to consider the composition of the film—the individual parts and choices made that come together to create the finished piece. Film analysis goes beyond the analysis of the film as literature to include camera angles, lighting, set design, sound elements, costume choices, editing, etc. in making an argument. The first step to analyzing the film is to watch it with a plan.

Watching Critically, Thinking Analytically

You’re probably here because you’ve been assigned a film to watch. Perhaps you’ve also been asked to write a film analysis. The good news? You are already more prepared than you might have guessed! If you are familiar with movies, television shows, YouTube videos, magazines, billboards, or advertisements, you can use your visual literacy to your advantage when watching film as part of an assignment.

Often film techniques are easiest to notice when they’re clunky or overly obvious. For example, have you ever watched a video on YouTube and noticed the “bad editing”? What about a “whodunit” that makes its clues all too obvious by showing them in close up? In both these examples, the choices of how to present a sequence of shots shape our understanding of what happens on screen. The challenge when watching a film analytically is to notice and name these techniques—even when they are being used more subtly.

Before watching the film

Here are some steps to help you get started on watching an assigned film for the purpose of analysis:

Start with your assignment. Review your assignment and identify any tasks you’ve been asked to perform and any questions you’ve been asked to address. Highlight these or list them out as a prompt for note taking.

Decide when, where, and how many times you will watch the film. How long is your film? Have you seen it before? It can help to watch any film once without taking notes, and then watching it a second time for analysis and note-taking. If you take notes without pausing, you may miss things (including the timestamps relevant to your observations), but pausing itself interrupts the film and the viewing experience. Watching a film straight through allows you to experience it as intended, while watching it a second time provides an opportunity to analyze.

Make a research plan. How much background information about the film, its director, history, or context will you need for your assignment? Whether the source is a lecture, a course reading, or your own research, when will you obtain this information? Another advantage of watching a film twice is the opportunity to research a film between viewings. You may find this research more interesting after you have seen the film once, and this information can inform your second viewing.

Study the film terms you will need to name what you observe. What film terms have you learned and how will you practice applying them while watching the film? For note-taking, will it help to develop abbreviations or shorthand (for example, “CU” for “close up”)? It can help to study terms before you begin, or you may find yourself searching for words. This tip sheet will use the following film terms:

- Track: Tracking shots occur when the entire camera apparatus moves along with the characters on-screen—literally “tracking” (following) their movements.

- Eyeline match: An eyeline match shot is an editing technique that shows a character looking and then shows the object of their gaze in the following shot, as if the camera follows the character’s line of sight.

- Tilt: A tilt is a camera movement in which the camera itself “tilts” upward. It may be helpful to think of the camera as a human head—it can move in the same ways our own heads can move!

- Zoom: A zoom is a lens adjustment that means an object on screen is brought closer to us, making it appear larger and take up more of the screen.

While watching the film

Let’s practice with this clip from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). After watching the clip straight through, try taking notes starting at 25 seconds in the following clip and going until 1:08.

As you take notes, ask yourself:

- When and where do you see the camera tracking?

- When and where do you see the camera tilt and zoom?

- How many eyeline match shots do you observe?

- What is highlighted by the eyeline match shots in this clip?

Include timestamps in your answers so you can find scenes later on. These questions focus primarily on camera movement, but you could also ask yourself about framing, lighting, lens choices, the score, or whatever stands out to you.

After watching the film

Now that you have some notes on this film clip, think about how films create meaning. Just as your literature professor may have written “don’t summarize!” in the margins of your essay, your film professor is likely to want you to say more about the film than just “what happened.”

Your next steps are to ask how the film’s formal elements that you’ve observed contribute to your understanding of the film. How do these formal elements relate to the plot, themes, or other aspects of film that have come up in your class?

- For example, you could ask yourself: How does the film position you as the viewer? Through lens choice and framing, do you inhabit the viewpoint of the protagonist or are you rather positioned as a spectator, watching or observing what unfolds on screen? (Perhaps the perspective or point of view even shifts throughout the film, confusing your position as spectator or changing your allegiance halfway through the movie).

- For another example, you could ask yourself: How does camera angle impact your understanding of on-screen relationships? For example, if one person is always shot from a low angle, making them appear larger than they actually are, what might this visual choice communicate about their role in the film?

These are just two examples of the kinds of questions you can ask as you watch. Use what you have been learning in your course to brainstorm additional questions.

To return to the clip shared above, it may help to know that the man portrayed is a detective who has been hired to investigate the troubled behavior of the woman portrayed. She says that she is possessed by the spirit of the woman in the portrait, who she says is her grandmother—but all is not as it seems. Review your notes to ask yourself how the formal elements of this scene may reflect or convey the progress of the detective’s investigation or the themes of this kind of detective story.

Next time you have a film assignment, take notes on your second viewing and ask yourself how the formal elements might complement, corroborate, or even subvert the narrative’s development. These observations can then serve as the foundation for a written film analysis.

Types of Film Analysis

Semiotic analysis

Semiotic analysis is the interpretation of signs and symbols, typically involving metaphors and analogies to both inanimate objects and characters within a film. Because symbols have several meanings, writers often need to determine what a particular symbol means in the film and in a broader cultural or historical context.

For instance, a writer could explore the symbolism of the flowers in Vertigo by connecting the images of them falling apart to the vulnerability of the heroine.

Here are a few other questions to consider for this type of analysis:

- What objects or images are repeated throughout the film?

- How does the director associate a character with small signs, such as certain colors, clothing, food, or language use?

- How does a symbol or object relate to other symbols and objects, that is, what is the relationship between the film’s signs?

Many films are rich with symbolism, and it can be easy to get lost in the details. Remember to bring a semiotic analysis back around to answering the question “So what?” in your thesis.

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis is an examination of the story elements, including narrative structure, character, and plot. This type of analysis considers the entirety of the film and the story it seeks to tell.

For example, you could take the same object from the previous example—the flowers—which meant one thing in a semiotic analysis, and ask instead about their narrative role. That is, you might analyze how Hitchcock introduces the flowers at the beginning of the film in order to return to them later to draw out the completion of the heroine’s character arc.

To create this type of analysis, you could consider questions like:

- How does the film correspond to the Three-Act Structure: Act One: Setup; Act Two: Confrontation; and Act Three: Resolution?

- What is the plot of the film? How does this plot differ from the narrative, that is, how the story is told? For example, are events presented out of order and to what effect?

- Does the plot revolve around one character? Does the plot revolve around multiple characters? How do these characters develop across the film?

When writing a narrative analysis, take care not to spend too time on summarizing at the expense of your argument. See our handout on summarizing for more tips on making summary serve analysis.

Cultural/Historical analysis

One of the most common types of analysis is the examination of a film’s relationship to its broader cultural, historical, or theoretical contexts. Whether films intentionally comment on their context or not, they are always a product of the culture or period in which they were created. By placing the film in a particular context, this type of analysis asks how the film models, challenges, or subverts different types of relations, whether historical, social, or even theoretical.

For example, the clip from Vertigo depicts a man observing a woman without her knowing it. You could examine how this aspect of the film addresses a midcentury social concern about observation, such as the sexual policing of women, or a political one, such as Cold War-era McCarthyism.

A few of the many questions you could ask in this vein include:

- How does the film comment on, reinforce, or even critique social and political issues at the time it was released, including questions of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality?

- How might a biographical understanding of the film’s creators and their historical moment affect the way you view the film?

- How might a specific film theory, such as Queer Theory, Structuralist Theory, or Marxist Film Theory, provide a language or set of terms for articulating the attributes of the film?

Take advantage of class resources to explore possible approaches to cultural/historical film analyses, and find out whether you will be expected to do additional research into the film’s context.

Mise-en-Scène Analysis

A mise-en-scène analysis attends to how the filmmakers have arranged compositional elements in a film and specifically within a scene or even a single shot. This type of analysis organizes the individual elements of a scene to explore how they come together to produce meaning. You may focus on anything that adds meaning to the formal effect produced by a given scene, including: blocking, lighting, design, color, costume, as well as how these attributes work in conjunction with decisions related to sound, cinematography, and editing. For example, in the clip from Vertigo, a mise-en-scène analysis might ask how numerous elements, from lighting to camera angles, work together to present the viewer with the perspective of Jimmy Stewart’s character.

To conduct this type of analysis, you could ask:

- What effects are created in a scene, and what is their purpose?

- How does this scene represent the theme of the movie?

- How does a scene work to express a broader point to the film’s plot?

This detailed approach to analyzing the formal elements of film can help you come up with concrete evidence for more general film analysis assignments.

How to Analyze a Film

Films are similar to novels or short stories in that they tell a story. They include the same genres: romantic, historical, detective, thriller, adventure, horror, and science fiction. However, films may also include sub-groups such as: action, comedy, tragedy, westerns and war. The methods you use to analyze a film are closely related to those used to analyze literature; nevertheless, films are multimedial. They are visual media made for viewers. Films take command of more of our senses to create special atmospheres, feelings or to bring out emotions.

Along with the literary elements such as plot, setting, characterization, structure, and theme, which make up the text or screenplay, there are many different film techniques used to tell the story or narrative. Attention is paid to sound, music, lighting, camera angles, and editing. What is important is to focus on how all the elements are used together in making a good film.

Below is a list of elements and questions to help you when analyzing films.

Film Facts

- Title of film

- Year film was produced

- Nationality

- Names of the actors

- Name of director

Genre

- What main genre does the film fall under? – romantic, historical, detective, thriller, adventure, horror, and science fiction.

- What sub-grouping does the film fall under? – action, comedy, tragedy, war and westerns.

Setting

Setting is a description of where and when the story takes place.

- Does it take place in the present, the past, or the future?

- What aspects of setting are we made aware of? – Geography, weather conditions, physical environment, time of day.

- Where are we in the opening scene?

Plot and structure

- What are the most important sequences?

- How is the plot structured?

- Is it linear, chronological or is it presented through flashbacks??

- Are there several plots running parallel?

- How is suspense built up?

- Do any events foreshadow what is to come?

Conflict

Conflict or tension is usually the heart of the film and is related to the main characters.

- How would you describe the main conflict?

- Is it internal where the character suffers inwardly?

- is it external caused by the surroundings or environment the main character finds himself/herself in?

Characterization

Characterization deals with how the characters are described.

- through dialogue?

- by the way they speak?

- physical appearance? thoughts and feelings?

- interaction – the way they act towards other characters?

- Are they static characters who do not change?

- Do they develop by the end of the story?

- What type of characters are they?

- What qualities stand out?

- Are they stereotypes?

- Are the characters believable?

Narrator and point of view

The narrator is the person telling the story.

- Is there a narrator in the film? Who?

- Point of view means through whose eyes the story is being told.

- Through whose eyes does the story unfold?

- Is the story told in the first person “I” point of view?

- Is the story told through an off-screen narrator?

Imagery

In films imagery are the elements used to create pictures in our minds. They may include:

- Symbols – when something stands not only for itself ( a literal meaning), but also stands for something else (a figurative meaning) e.g. The feather in the film Forrest Gump symbolizes his destiny.

- What images are used in the film? e.g. color, objects etc.

- Can you find any symbols?

Theme

- What are the universal ideas that shine through in the film (in other words, what is it about, in general)?

Cinematic Effects

Soundtrack

- includes both dialogue and music, as well as all the other sounds in a film.

- enhances the atmosphere of the film (what effect does the choice of music have? Does it suit the theme?)

- Are any particular sounds accentuated?

Use of the camera

- A camera shot is based on the camera’s distance from the object.

- The four basic shots used in films are:

- a close-up – a very close shot where the camera lens focuses on some detail or the actor’s face.

- medium shot – a shot where the camera lens picks up some background or upper half of the actor.

- full shot – a shot where the camera lens has full view of the actor.

- long shot – shot taken at a distance from an object.

- What camera shots can you identify in the film? How are they used?

- A camera angle is how the camera is tilted while filming.

- straight-on angle – The camera is at the same height as the object.

- high angle – The camera is filming from above the object.

- low angle – The camera is looking up at the object.

- oblique angle – The camera is tilted sideways.

- Does the way in which the camera is held say anything about the character?

Lighting

- Lighting focuses the audience’s attention on the main character or object in a film.

- It also sets the mood or atmosphere.

- While high-key lighting is bright and illuminating, low-key lighting is darker with a lot of shadows.

- What special lighting effects are used during the most important scenes?

- Filters are often used to soften and reduce harsh contrasts. They can also be used to eliminate haze, ultraviolet light or glare from water when shooting outside.

- Using color like red or orange can be used to enhance the feeling of a sunset.

- Can you find any examples where a filter has been used in the film?

- What effect did using a filter have on the scene?

- What colors are most dominant?

Editing

Editing is the way in which a film editor together with the director cuts and assembles the scenes. The way the scenes are joined together creates the rhythm of the motion picture. Scenes can be long and drawn out or short and choppy.

- Can you see a pattern to how the scenes are cut?

- How would you describe the pace/tempo of the film?

Case Study:

Wonder Woman

Synopsis

From The Guardian:

Why Wonder Woman is a Masterpiece of Subversive Feminism

Yes, the new movie sees its titular heroine sort of naked a lot of the time. But the film-makers have still worked to turn sexist Hollywood conventions on their head

By Zoe Williams, 5 June 2017

The chances are you will read a feminist takedown of Wonder Woman before you see the film. And you’ll probably agree with it. Wonder Woman is a half-god, half-mortal super-creature; she is without peer even in superhero leagues. And yet, when she arrives in London to put a stop to the war to end all wars, she instinctively obeys a handsome meathead who has no skills apart from moderate decisiveness and pretty eyes. This is a patriarchal figment. Then, naturally, you begin to wonder why does she have to fight in knickers that look like a fancy letterbox made of leather? Does her appearance and its effect on the men around her really have to play such a big part in all her fight scenes? Even my son lodged a feminist critique: if she were half god, he said, she would have recognised the god Ares immediately – unless he were a better god than her (being a male god).

I agree with all of that, but I still loved it. I didn’t love it as a guilty pleasure. I loved it with my whole heart. Wonder Woman, or Diana Prince, as her civilian associates would know her, first appeared as a character in DC Comics in 1941, her creator supposedly inspired by the feminism of the time, and specifically the contraception pioneer Margaret Sanger. Being able to stop people getting pregnant would be a cool superpower, but, in fact, her skills were: bullet-pinging with bracelets; lassoing; basic psychology; great strength and athleticism; and being half-god (the result of unholy congress between Zeus and Hyppolyta). The 1970s TV version lost a lot of the poetry of that, and was just all-American cheesecake. Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman made her cinematic debut last year in Batman v Superman, and this first live-action incarnation makes good on the character’s original premise, the classical-warrior element amped up and textured. Her might makes sense.

Yes, she is sort of naked a lot of the time, but this isn’t objectification so much as a cultural reset: having thighs, actual thighs you can kick things with, not thighs that look like arms, is a feminist act. The whole Diana myth, women safeguarding the world from male violence not with nurture but with better violence, is a feminist act. Casting Robin Wright as Wonder Woman’s aunt, re-imagining the battle-axe as a battler, with an axe, is a feminist act. A female German chemist trying to destroy humans (in the shape of Dr Poison, a proto-Mengele before Nazism existed) might be the most feminist act of all.

Women are repeatedly erased from the history of classical music, art and medicine. It takes a radical mind to pick up that being erased from the history of evil is not great either. Wonder Woman’s casual rebuttal of a sexual advance, her dress-up montage (“it’s itchy”, “I can’t fight in this”, “it’s choking me”) are also feminist acts. Wonder Woman is a bit like a BuzzFeed list: 23 Stupid Sexist Tropes in Cinema and How to Rectify Them. I mean that as a compliment.

Yet Wonder Woman is not a film about empowerment so much as a checklist of all the cliches by which women are disempowered. So it leaves you feeling a bit baffled and deflated – how can we possibly be so towering a threat that Hollywood would strive so energetically, so rigorously, for our belittlement? At the same time, you are conflicted about what the fightback should look like. Because, as every reviewer has pointed out, Wonder Woman is by no means perfect.

The woman who can fight is not new; from Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in Alien, to Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor in The Terminator, this idea has a long pedigree. Connor was a far-fetched feminist figure because her power was concentrated in her ambivalent maternal love – like a hypothetical tiger mother, which doesn’t do a huge amount for female agency. She is still an accessory for male power, just on the other side of the mother/whore dichotomy. Ripley, being the same gender as her foe, recast action as a cat-fight, with all the sexist bullshit that entails (hot, sweaty woman saying “bitch” a lot – a classic pornography trope).

But the underlying problem is that the male fighter is conceived as an ego ideal for a male audience, who would imagine themselves in the shirt of Bruce Willis or mankini of Superman and get the referred thrill of their heroism. If you are still making the film for a male gaze, the female warrior becomes a sex object, and her fighting curiously random, like pole dancing – movement that only makes sense as display, and even then, only just. That was always the great imponderable of Lara Croft (as she appeared in the video-game, not the film): the listlessness of her combat, the slightly dreamlike quality of it. Even as it was happening, it was hard to remember why. When Angelina Jolie made her flesh, I thought she brought something subversive to the role; something deliberated, knowing and a bit scornful, as though looking into the teenage gamer’s soul and saying: “You don’t know whether that was a dragon, a dinosaur or a large dog. You are just hypnotised by my buttocks.”

The fighter as sex symbol stirs up a snakepit of questions: are you getting off on the woman or the violence? An unbreakable female lead can be liberating to the violent misogynist tendency since the violence against her can get a lot more ultra, and nobody has to feel bad about it, because she’ll win.

This is tackled head on in Wonder Woman. The tension, meanwhile, between the thrill of the action, which is what combat is all about, and the objectification, which is what women are all about, is referenced when Wonder Woman hurls someone across a room and an onlooker says: “I’m both frightened, and aroused.” A word on the fighting: there’s a lot of hurling, tons of lassoing, much less traditional fighting, where people harm one another with punches. This is becoming a sub-genre in films: “the kind of fighting that is ladylike”. It almost always involves bows and arrows, for which, as with so many things, we can thank Jennifer Lawrence in The Hunger Games. The way Lawrence fights is so outrageously adroit and natural that she makes it look as though women have been doing it all along, and men are only learning.

I find it impossible to imagine the feminist action-movie slam-dunk; the film in which every sexist Hollywood convention, every miniature slight, every outright slur, every incremental diss was slain by a lead who was omnipotent and vivid. That film would be long and would struggle for jokes. Just trying to picture it leaves you marvelling at the geological slowness of social progress in this industry, which finds it so hard to create female characters of real mettle, even when they abound in real life. Wonder Woman, with her 180 languages and her near-telepathic insights, would stand more chance of unpicking this baffler than Superman or Batman. But the answer, I suspect, lies in the intersection between the market and the culture; the more an art-form costs, the less it will risk, until the most expensive of them – blockbusters – can’t change at all. In an atmosphere of such in-built ossification, the courage of Wonder Woman is more stunning even than her lasso.

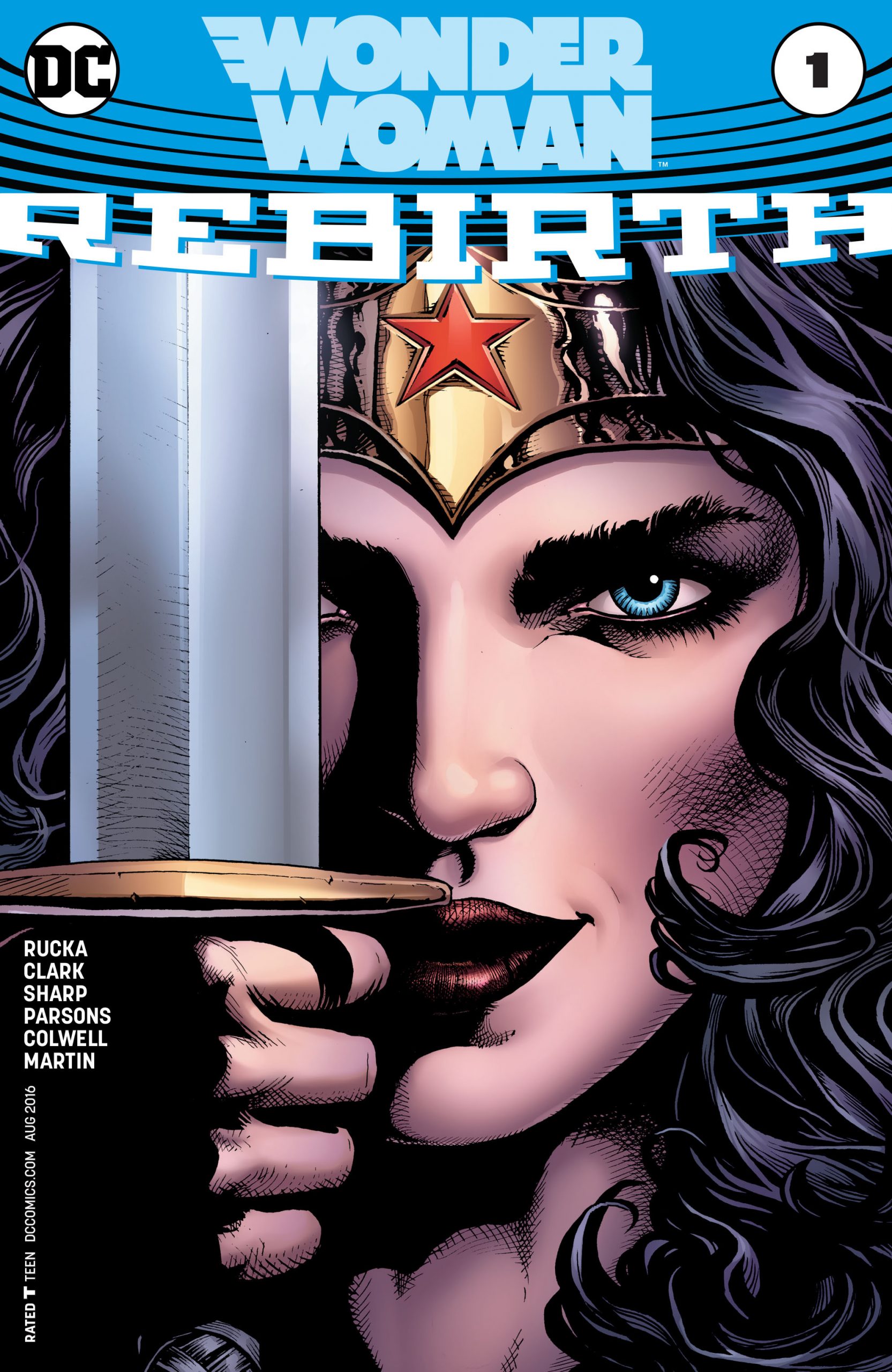

Wonder Woman in Comics

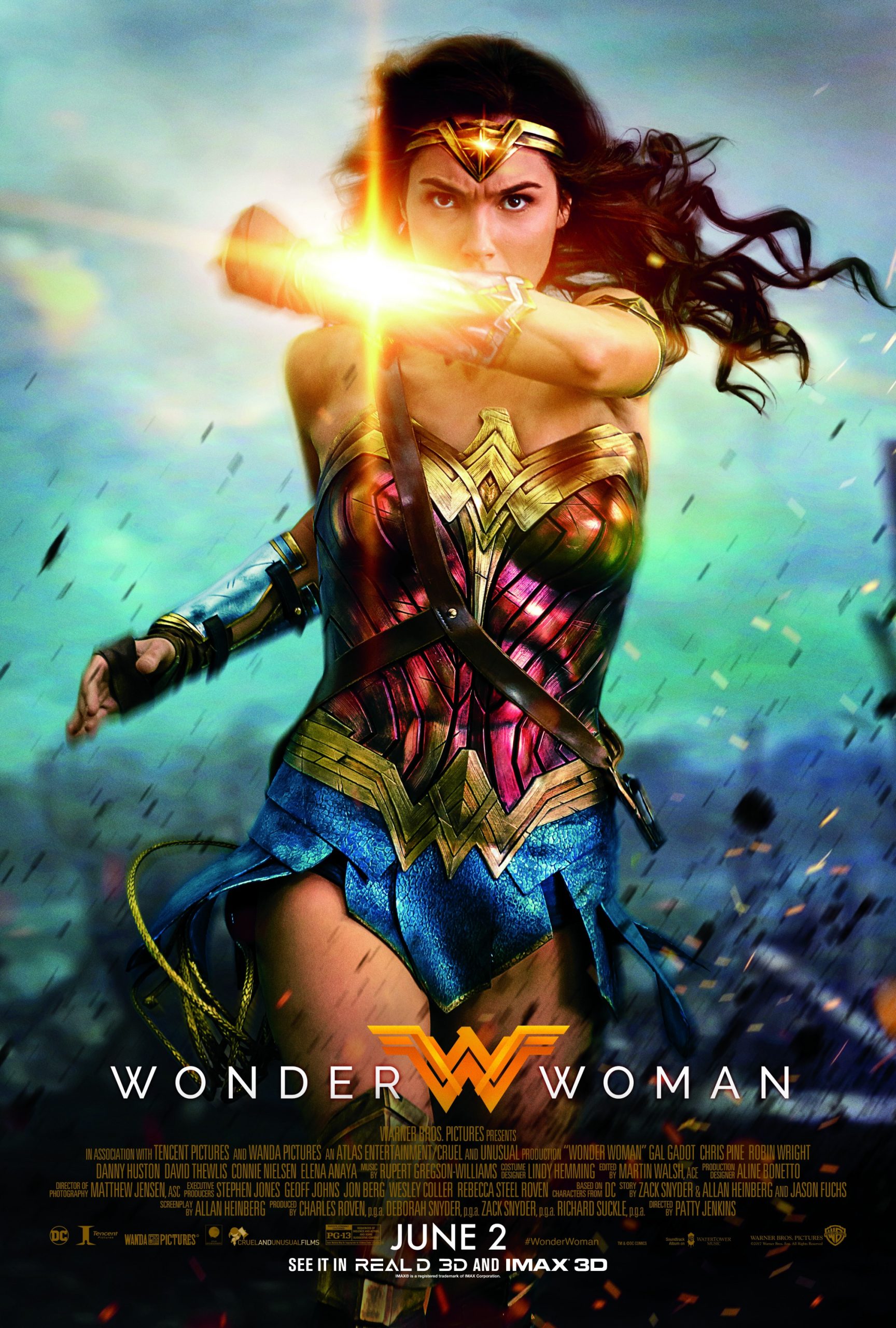

Wonder Woman on Film:

Warner Bros./DC (2017)

Where to Watch: