18

The history of ballet begins around 1500 in Italy. Terms like “ballet” and “ball” stem from the Italian word “ballare,” which means “to dance.”

Ballet originated in the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century. Noblemen and women were treated to lavish events, especially wedding celebrations, where dancing and music created an elaborate spectacle. Dancing masters taught the steps to the nobility, and the court participated in the performances. In the 16th century, Catherine de Medici — an Italian noblewoman, wife of King Henry II of France and a great patron of the arts — began to fund ballet in the French court. Her elaborate festivals encouraged the growth of ballet de cour, a program that included dance, decor, costume, song, music and poetry.

At first, the dancers wore masks, layers upon layers of brocaded costuming, pantaloons, large headdresses, and ornaments. Such restrictive clothing was sumptuous to look at but difficult to move in. Dance steps were composed of small hops, slides, curtsies, promenades, and gentle turns. Dancing shoes had small heels and resembled formal dress shoes rather than any contemporary ballet shoe we might recognize today.

The official terminology and vocabulary of ballet was gradually codified in French over the next 100 years, and during the reign of Louis XIV, the king himself performed many of the popular dances of the time. Professional dancers were hired to perform at court functions after King Louis and fellow noblemen had stopped dancing.

A whole family of instruments evolved during this time as well. The court dances grew in size, opulence, and grandeur to the point where performances were presented on elevated platforms so that a greater audience could watch the increasingly pyrotechnic and elaborate spectacles.

A century later, King Louis XIV helped to popularize and standardize the art form. A passionate dancer, he performed many roles himself, including that of the Sun King in Ballet de la nuit. His love of ballet fostered its elevation from a past time for amateurs to an endeavor requiring professional training.

By 1661, a dance academy had opened in Paris, and in 1681 ballet moved from the courts to the stage. The French opera Le Triomphe de l’Amour incorporated ballet elements, creating a long-standing opera-ballet tradition in France. By the mid-1700s French ballet master Jean Georges Noverre rebelled against the artifice of opera-ballet, believing that ballet could stand on its own as an art form. His notions — that ballet should contain expressive, dramatic movement that should reveal the relationships between characters — introduced the ballet d’action, a dramatic style of ballet that conveys a narrative. Noverre’s work is considered the precursor to the narrative ballets of the 19th century.

From Italian roots, ballets in France and Russia developed their own stylistic character. By 1850 Russia had become a leading creative center of the dance world, and as ballet continued to evolve, certain new looks and theatrical illusions caught on and became quite fashionable. Dancing en pointe (on toe) became popular during the early part of the nineteenth century, with women often performing in white, bell-like skirts that ended at the calf. Pointe dancing was reserved for women only, and this exclusive taste for female dancers and characters inspired a certain type of recognizable Romantic heroine – a sylph-like fairy whose pristine goodness and purity inevitably triumphs over evil or injustice.

In the early twentieth century, the Russian theatre producer Serge Diaghilev brought together some of that country’s most talented dancers, choreographers, composers, singers, and designers to form a group called the Ballet Russes. The Ballet Russes toured Europe and America, presenting a wide variety of ballets. Here in America, ballet grew in popularity during the 1930’s when several of Diaghilev’s dancers left his company to work with and settle in the U.S. Of these, George Balanchine is one of the best known artists who firmly established ballet in America by founding the New York City Ballet. Another key figure was Adolph Bolm, the first director of San Francisco Ballet School.

Pointe Shoes

The Pointe Shoe is synonymous with ballet and ballerina’s around the world. While we might take them for granted as having always been a part of the long history of Ballet, the pointe shoe has gone through a very long and interesting history itself. It might surprise you to learn that the art of Ballet was established 200 years before the pointe shoe was developed and dancers rose up onto the tips of their toes to dance.

The Royal Academy of Dance, Académie Royale de Danse, was the first dance institution to be founded in the western world. It was established in France in 1661 as a Theatre, Dance and Opera institution by the French king, Louis XIV. Twenty years after it was founded, the first official Ballet productions went to stage.

This academy placed Ballet within the creative arts and distinguished it as it’s own form of dance and performance. While Ballet had been practiced in Europe prior to this time, it’s official birth place in France cemented French as the international language of Ballet. Ballet classes around the world are still directed and run in French.

The first Ballet shoes worn by the dancers of the Royal Academy of Dance were heeled slippers. These shoes were quite difficult to wear and prohibited any jumps and a lot of technical movements. The heeled slipper did not stay around for very long. No one knows exactly when the heel was dropped and ballerinas wore non-heeled shoes, but the abandonment of the heel meant that the dancers could do far more than ever before. It is rumored that Marie Camargo of the Paris Opera Ballet may have been the first dancer to take the heels from the slippers.

The new flat bottomed slippers spread quickly throughout the Ballet community as dancers were liberated by the abandonment of the heel. The new flat bottomed slippers worn during the 18th century are much like the demi-pointe rehearsal and learning shoes worn by young ballerina’s in classes today. They were secured to the feet with ribbons around the ankle and were pleated under the toes for a better fit. The new slippers allowed for a full extension and enabled the dancer to use the whole foot.

The first dancers to rise up onto their toes did so with an invention by Charles Didelot in 1795. His “flying machine” lifted dancers upward, allowing them to stand on their toes before leaving the ground. This lightness and ethereal quality was so well received by audiences and, as a result, choreographers began to look for ways to incorporate more pointe work into their pieces.

As dance progressed into the 19th century, the emphasis on technical skill increased, as did the desire to dance en pointe without the aid of wires. Marie Taglioni is often credited as being the first to dance on pointe but like many things in the early history of Ballet, no one knows for sure.

In 1832, when Marie Taglioni first danced the entire La Sylphide en pointe, her shoes were nothing more than modified satin slippers; the soles were made of leather and the sides and toes were darned to help the shoes hold their shapes. Because the shoes of this period offered no support, dancers would pad their toes for comfort and rely on the strength of their feet and ankles for support.

The next substantially different form of pointe shoe appeared in Italy in the late 18th century with a modified toe area which was the beginning stages of what we now call the toe box. Dancers like Pierina Legnani wore shoes with a sturdy, flat platform at the front end of the shoe, rather than the more sharply pointed toe of earlier models.

The Italian school could now push technique to the limit in order to achieve dazzling virtuosic feats. These more sturdy toe areas were a Ballerina’s secret weapon, a closely guarded trade secret, for turning multiple pirouettes: spotting.

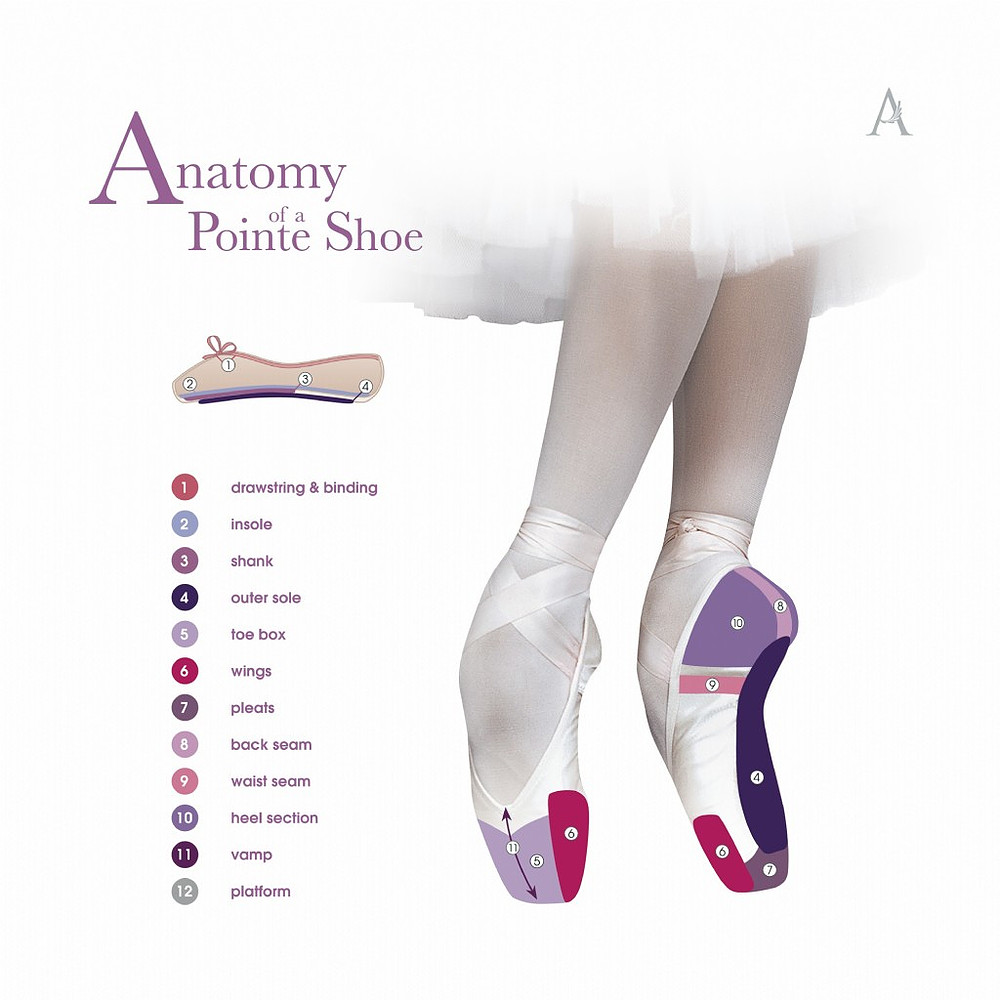

These shoes went on to included a box—made of layers of fabric—for containing the toes, and a stiffer, stronger sole. They were constructed without nails and the soles were only stiffened at the toes, making them nearly silent. As the Pointe Shoe developed, so did Ballet itself. As the shoes allowed dancers to do more and more, the dancers started to want more from their shoes.

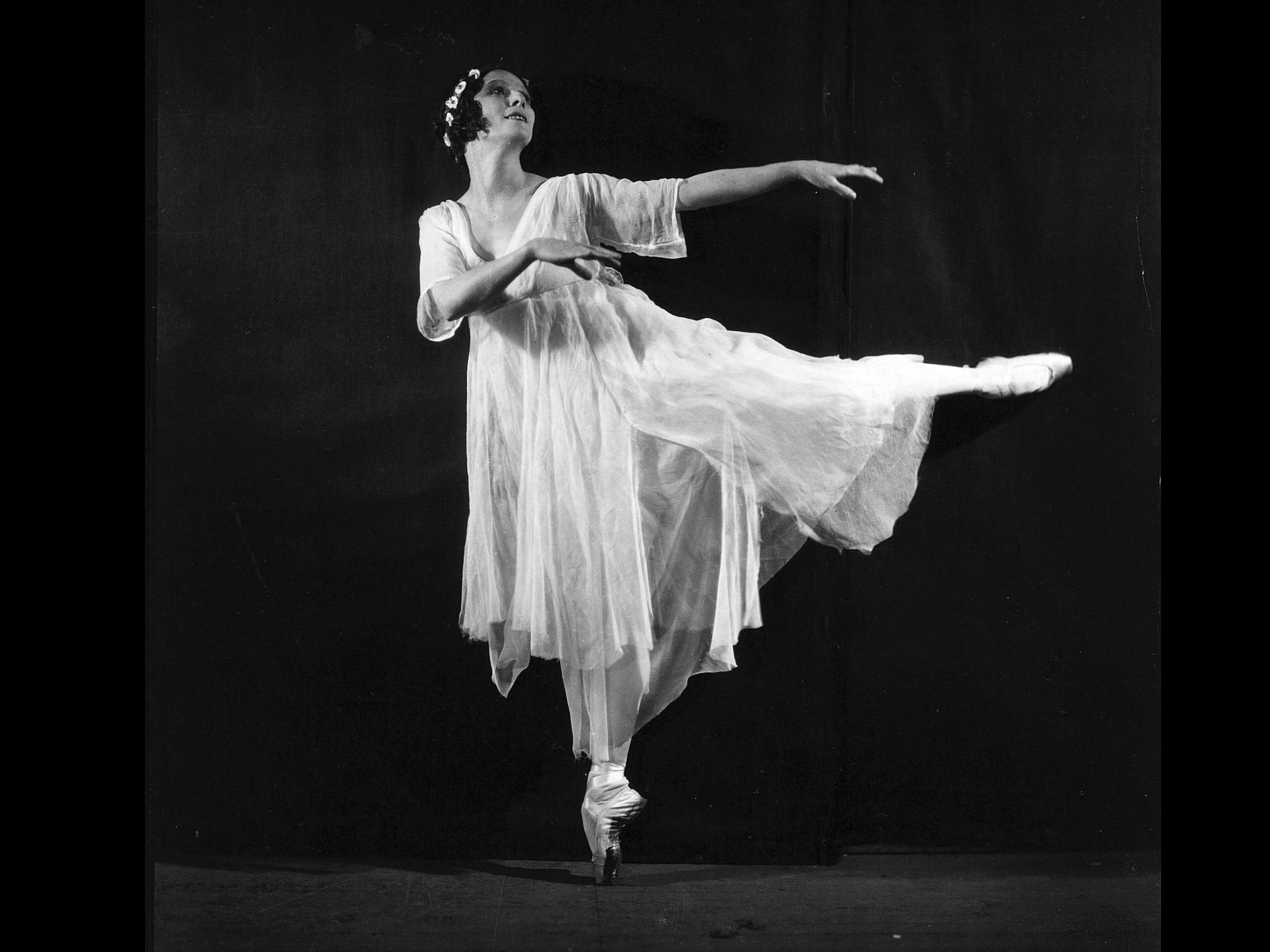

The birth of the modern pointe shoe is often attributed to the early 20th-century Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, who was one of the most famous and influential dancers of her time. Pavlova had particularly high, arched insteps, which left her vulnerable to injury when dancing en pointe. She also had slender, tapered feet, which resulted in excessive pressure on her big toes. To compensate for this, she inserted toughened leather soles into her shoes for extra support and flattened and hardened the toe area to form a box.

The soft slippers used by these ballerinas were far different from the “blocked” toe shoes that eventually appeared in their earliest form in the 1880s. (Previously, dancers also spent far less time on pointe than ballerinas do today.)

Ballet dancers in the early part of this century also wore shoes that would seem unmanageably soft today. Tamara Karsavina was said to dance in toe shoes of Swiss goatskin, while the ballerina Pierozi reportedly wore only Moroccan leather. It was fundamental to the development of Ballet technique that the pointe shoes be stiffened and stronger to support longer balances and challenging pirouettes.

Today most toe shoes are fashioned of layers of satin stiffened with glue, with a narrow sole often made of leather.

Depending on the Ballet dancers experience and skill, a pair of Pointe shoes can last between 2 to 12 hours of dancing. If a dancer is attending a one hour pointe shoe class per week; her pointe shoes will last about three months. For a professional dancer, her shoes will last far less time. A Professional Ballerina can go through 100 and 120 pointe shoes in a single dancing year. Some pointe shoes will only last a single performance in a heavy duty role where the shoes are worked hard. Ballet Companies will often employ professional pointe shoe makers and fitters to work within the company producing and buying over 8,000 shoes during the dance year.

Even different ballet role demands different strengths and flexibility in their shoes. “For the technically and physically demanding role of the Black Swan in “Swan Lake,” a strong shoe with a lot of support is required, whereas the role of the sylph in “La Sylphide” has more jumps and less pirouettes, so a light, gentle shoe is needed.”

The pointe shoe has remained very much unchanged for the last 200 years. Recent developments and changes have begun to appear now within companies that produce Ballet wear such as Nike in conjunction with Bloch Dance wear have designed these shoes called Arc Angel by Guercy Eugene. These shoes have come from a need to protect and advance the support of Ballerina’s very important asset – their feet!