10

Table of Contents

- Key Facts

- Context

- Characters

- Themes

- Symbols

- Adaptations

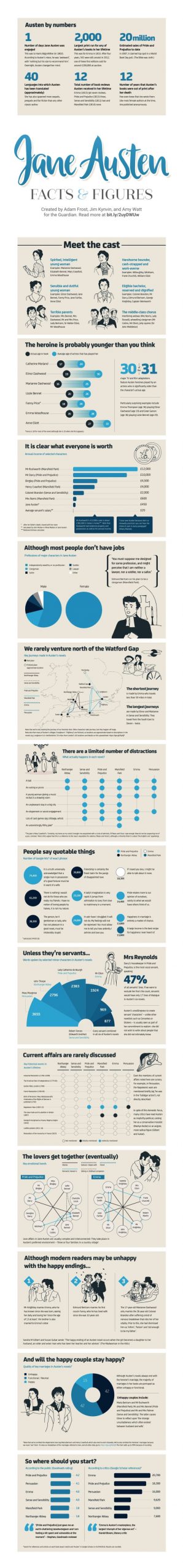

Key Facts

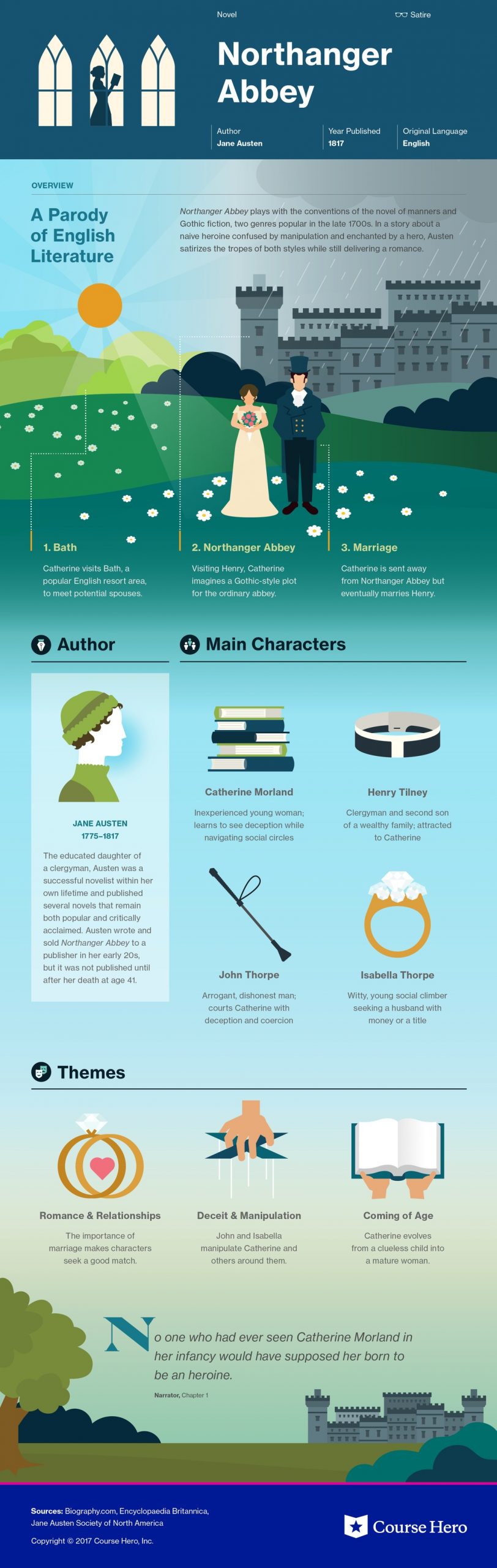

- Full Title: Northanger Abbey

- When Written: 1798-1803 (this was probably the first mature novel that Jane Austen finished)

- When Published: 1817 (Even though she wrote this novel first, it was the last the published, six months after she died)

- Where Written: Steventon, Hampshire, England (Jane Austen’s hometown); Bath, Somersetshire, England; Chawton, Hampshire, England (where Jane Austen edited her novels); Winchester, Hampshire, England (where Jane Austen died)

- Where Set: Fullerton, Wiltshire, England (Catherine’s hometown); Bath, Somerset, England; Northanger Abbey, Gloucestershire, England (the Tilney home); Woodston, Gloucestershire, England (Henry Tilney’s home); Putney, Greater London, England (the Thorpe home)

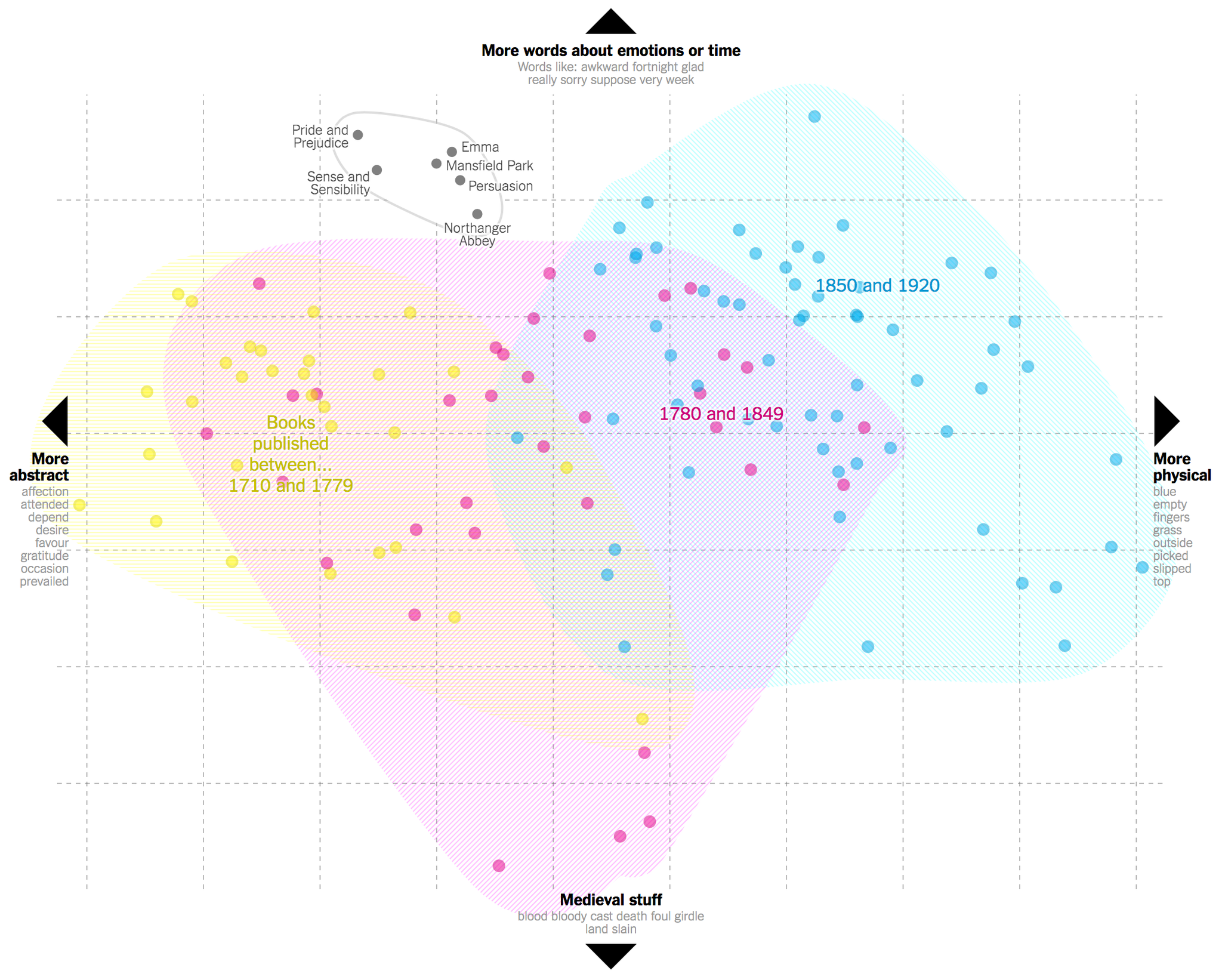

- Literary Period: Austen’s novels are early examples of the 19th-century realist tradition and satires of the sentimentalist novels popular at the time when she wrote.

- Climax: Henry Tilney discovers Catherine snooping around Northanger Abbey and she confesses her suspicion that his father is a murderer.

- Point of View: Northanger Abbey is told with a third-person limited perspective and an intrusive narrator. The narrator usually tracks Catherine’s experiences and thoughts, but occasionally describes other characters’ perspectives on the action. The narrator also sometimes speaks directly to the reader, as an essayist presenting a position might do. For instance, when Catherine is deliberating over what to wear to a ball, the narrator cuts in to present some general thoughts on whether it is worthwhile to spend time thinking about fashion.

Northanger Abbey was initially written from 1797 to 1798. It was sold in 1803 as Susan. Although it was advertised, it never went on sale. In 1809 Jane Austen wrote and asked about the delay, signing the letter Mrs. Ashton Dennis (or MAD). The publisher offered to sell it back to her at the price he had paid her, to which she agreed in 1815. She renamed it Catherine and prepared to publish it, but in March 1817 she sent a letter to her niece saying she had set it aside.

Only two months later Jane Austen died. The book was published by her brother, Henry Austen, in December 1817 (the title page says 1818, however) as part of a four-volume set along with Persuasion, which Jane Austen had entitled The Elliots.

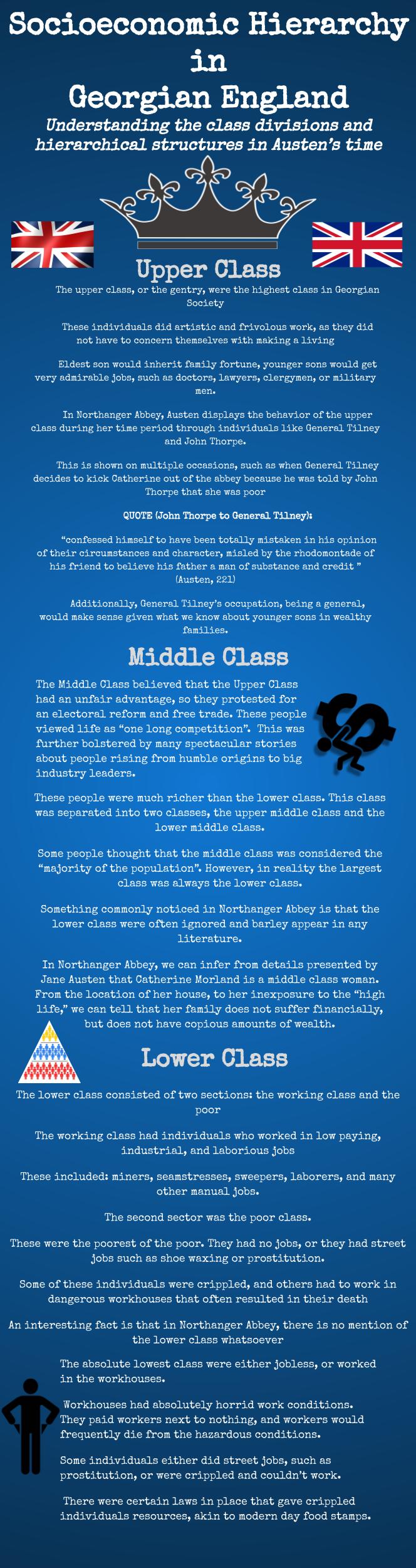

Context of the Regency Era

Bath

Bath, England, was, after London, the center of high society. It was already a popular resort area when medieval Roman bathhouses were discovered there in the 1700s, but its popularity increased afterward. The pump-room, which is central to the daily life in Northanger Abbey, was a place where one could not only go to drink the mineral waters but also to see and be seen.

The character of Catherine Morland’s presence in Bath, especially accompanied by the wealthy Mr. and Mrs. Allen, leads to the mistaken notion that she is a young woman of means, possibly the goddaughter of the childless couple who have brought her with them. That she attracts the attention of the wealthy Thorpe family and General Tilney is not surprising in this context. A not insignificant part of society was involved in making a “good match.” Being in the second city where society would gather, dressed fashionably by Mrs. Allen, and in the company of a wealthy couple would mark her as marriageable.

Ballroom Etiquette

- The focus was to be a social gathering/event.

- Gentlemen, including married men, were supposed to keep an eye out for any single ladies who were not dancing, to keep them involved.

- Ladies didn’t ask men to dance and in order to dance with someone you would need to be formally introduced beforehand.

- Ladies could only refuse a dance with a man if they were already engaged to dance with someone else or were planning to sit out on that particular dance.

- If a lady refused to dance with a man, it would be an insult to the man himself and the host of the party for inviting him. It was seen as complete impoliteness and of great disrespect.

- Ladies could only dance with the same partner for one or two dances (unless they were courting, engaged, or married).

- Each dance was intricately choreographed and would last for 15-20 minutes. Dances gave young men and women a chance to converse without chaperones hovering.

- The dance schedule was known in advance, and ladies would keep a dance card tied around their wrists to keep track of which dance they had promised to which gentleman.

- Social classes were prominent and people would associate with people of the same social level as themselves only.

- There were some rules such as the expectation that you must look presentable. Men had to wear a full black suit. Women would wear pastel colors to public balls, but white was the only color allowed at private balls.

The Marriage Market

- Propriety involves conforming to behavior while impropriety involves a person not conforming to behavior.

- Dancing was an integral part of 18th-century life. It allowed single people to meet, providing the opportunity for courtship.

- Strict rules were to be followed for propriety to remain, particularly in regard to a woman’s reputation.

Men: Gothic Heroes & Gothic Villians?

- Throughout the novel, Austen criticizes characters, including men, based on their actions.

- A conventional Gothic Hero is mysterious, dark, poetic, and brooding. Mr. Tilney is not a conventional hero as he is jovial and fun and likes clothing and reading.

- Mr. Tilney begins by following the conventions of Ballroom etiquette as he is formally introduced to Catherine by the host and compliments her.

- However, after the dance, he sits down with Catherine in an attempt to get to know her better. At this point, he does not follow the ballroom conventions as he is not being sociable with all who are present. This tells us that his character is more genuine and he has a tendency to follow his heart and not social expectations.

- Austen presents the character of John Thorpe as particularly stupid when he ridicules Gothic novels yet claims to like Ann Radcliffe’s works. Austen uses the character of Mr. Tilney to contrast and emphasize just how stupid Mr. Thorpe is. She also does this by providing a comparison:

- John Thorpe: “Udolpho, oh Lord not I.”

- Henry Tilney: “I myself have read hundreds and hundreds.”

Gothic Architecture

During the English Reformation of the 1530s and 1540s, King Henry VIII created the Protestant Church of England and sought to undermine all institutions of Catholic power. To this end, he passed a law for the Dissolution of the Monasteries. This act allowed Catholic lands and buildings to be seized by the state. Many of them were sold to wealthy families of the era, while others fell into disrepair. The many monks and nuns who lived on these properties were expelled from their homes, while a new class of English landowners came to power. Although these events occurred more than 250 years before the time period when Northanger Abbey is set, their impact can still be felt throughout the novel. The suffering of the nuns and monks expelled from these places is a theme in the Gothic novels that Catherine loves to read, and the fact that these buildings and lands were taken over by landowners who did not care about their traditions is reflected in the character of General Tilney, who renovates without any regard for the historic value of Northanger Abbey.

Novels

Catherine is obsessed with Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, and Sentimental novels like Frances Burney’s Camilla and Samuel Richardson’s novel The History of Sir Charles Grandison are referred to throughout the book and form important touchstones for the plot. While sentimental novels focused on a heroine who faced many trials and tribulations on her way to finding love, eliciting a sympathetic reaction from the reader, gothic novels took this plot and placed it in an exotic and frightening setting. Northanger Abbey satirizes the conventions of Sentimental novels, as well as the gothic novels which formed an important subset of the Sentimental novel.

An omniscient (all-seeing, all-knowing) narrator usually stays in the background; however, in Austen’s novel, the Omniscient narrator interjects into the narrative. In the period of which Northanger Abbey was written, cheaper printing took publishing forward and more novels were published. Although more novels were published, there was a social contempt that Novels were inferior to academic books. Jane Austen wrote a defense of novels and their reputation for being “trash.” Some points she makes:

- There seems to be a general tendency to slander authors of novels

- Novels display the greatest powers of the mind.

- It is easy to read academically based novels, but you learn so much more in fictional novels as they have wit, genius, and taste.

- On top of having these qualities, the knowledge that can be gained is also written in the best language and manner.

- Even novel writers themselves do not take enough pride in their work.

The novel of manners is a realistic genre in which the concern with rules, society, and convention is a driving force. The first half of Northanger Abbey reflects the convention of a novel of manners: A heroine is under the care of a wealthy childless couple. With their support, she is provided fashionable clothing and taken to Bath, the second city for the members of society at that time to pursue their leisure. With them she attends the pump-room, dances, the theater, and shops.

The humorous misunderstandings that complicate the relationships in Northanger Abbey stem from the unspoken rules of society. Catherine rebuffs Henry’s first invitation to dance because her dances are promised to John. Henry and Eleanor are rebuffed when Catherine is not home, although they had made plans with her. Catherine is rebuffed at their door when, after first being told Eleanor is at home, the servant returns and lies that, in fact, she is not.

Further difficulties in Catherine’s friendship with Isabella stem from Catherine’s naïveté, which is contrasted with Isabella’s ongoing deceit and manipulation. Isabella, who grasps Catherine as a friend instantly, assumes Catherine is wealthy and values her more highly because of it. But Catherine’s unfamiliarity with society leaves her unsure of the right choices—and subject to Isabella’s deceit, despite the latter’s increasing transparency.

The latter half of Northanger Abbey follows the conventions of the Gothic novel for the purpose of satire or humor. The Gothic novel is believed to have begun with English writer Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764). Common traits of the Gothic novel include:

- settings such as cloudy skies at night, a full moon, graveyards, castles, abbeys, ruins, secret passageways, or hidden doors;

- sounds in the night—owls, screams, laughter, or footsteps;

- characters such as an innocent heroine, a rescuing hero, a villain with a dark secret, and a kidnapper;

- mood of apprehension, fear, terror, horror, suspense, or mystery;

- a sense of coming disaster; and

- supernatural elements.

Gothic novels were, by and large, written and read by women. They were not considered to be serious literature, in part due to both their formulaic and sensational nature. As a female author, Austen triumphs over such criticism by at once mastering the genre and satirizing it.

In Northanger Abbey, the heroine, Catherine Morland, is anything but the traditional heroine of a Gothic novel. Rather than being intelligent, rich, beautiful, or tragic, Catherine is naive and silly. As an avid fan of Gothic fiction, she repeatedly relies on such fiction as a template for interpreting her experiences, often to mistakenly comic effect. When Catherine travels to the Tilney estate of Northanger Abbey, she anticipates a setting that matches her Gothic reading—an abbey, filled with secrets. Henry Tilney encourages this fantasy by telling her a Gothic novel–style story set in Northanger Abbey. However, the secrets found in the locked cupboard in Catherine’s room turn out to be nothing but old receipts, and General Tilney’s dark secret is not that he’s a murderer but that he thinks Catherine is an heiress.

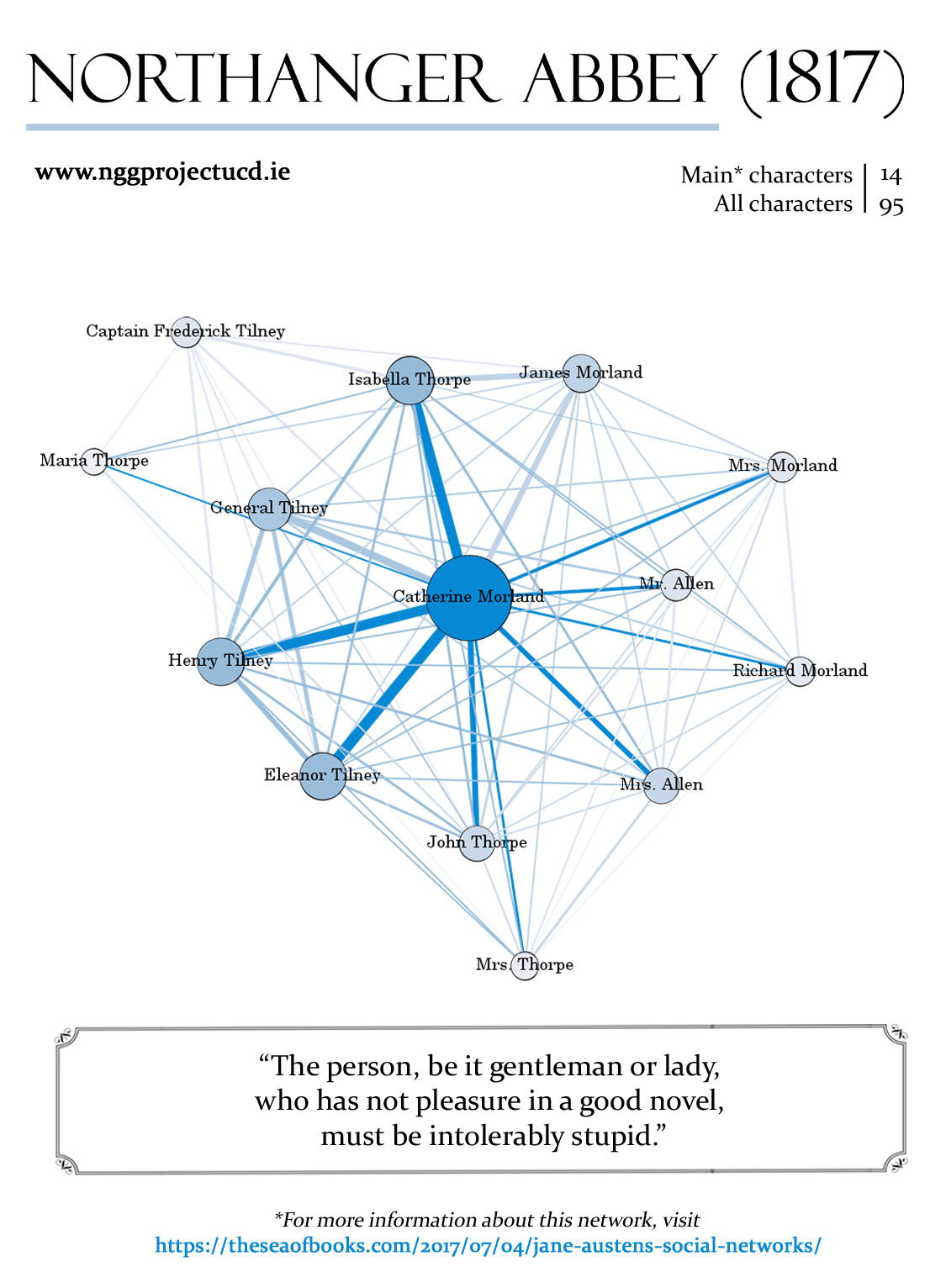

Characters

Narrator

The identity of the Narrator is unknown, and the narration usually occurs in the third-person. The narrator has special access to Catherine’s thoughts and feelings, but also sometimes gives a brief sense of what the other characters are thinking and feeling. The narrator also occasionally intrudes into the narrative to provide a broader perspective on an issue raised by the story, like the importance of dress or the plight of novelists who are looked down upon. In these moments, the narrator resembles an essayist, seeking to put forward a thesis and provide supporting arguments.

Catherine Morland

A seventeen-year-old raised in a rural parsonage with nine brothers and sisters, Catherine Morland is open, honest, and naïve about the hypocritical ways of society. Her family is neither rich nor poor, and she is unaware of how much stock many people put in wealth and rank. Catherine was a plain little girl, and her parents never expected very much from her, though she has grown more attractive as she has entered her late teens. Catherine loves novels, but has not read many because not many new books are available in the out-of-the-way town where she was raised. She is especially obsessed by Gothic novels set in castles and abandoned abbeys, and hopes to experience some of the thrills portrayed in these novels herself. At the start of the novel, she has very little experience judging people’s characters or intentions, and does not trust her own intuition. When she is taken to the holiday town of Bath by the Allens, wealthy friends of her family, and meets the Tilneys and Thorpes, she begins to learn the ways of the world. Over the course of the novel, she proves herself capable of learning from the experiences she has throughout the novel, even as she maintains her honesty, goodness, and loyalty to those whom she loves.

Isabella Thorpe

A conniving, beautiful, and charming social-climber of twenty-one, Isabella befriends Catherine because Isabella believes the Morlands to be as wealthy as their neighbors the Allens, and she wishes to marry Catherine’s brother James. Isabella often uses reverse psychology, saying the opposite of what she means to influence others to do what she wants them to do. Isabella’s hypocrisy and desire to marry for money are clear to those, like the Tilney siblings, who are more experienced than Catherine.

John Thorpe

A college friend of James Morland and brother to Isabella Thorpe, John Thorpe is an unscrupulous, rude braggart. He is a boring conversationalist who is only interested in horses, carriages, money and drinking, and lies whenever he thinks it will impress others or force them to give way to his will. He wishes to marry Catherine because he believes her to be wealthy, but he is so rude and self-centered that, although he sees himself as courting Catherine, she completely fails to understand his true intentions.

James Morland

Another Morland (Catherine’s brother) who fails to suspect those he meets of hypocrisy, James is a loving brother, son, and friend who is easily manipulated by the Thorpes. He falls in love with Isabella and never seems to realize that she is a fortune-hunter. Eager to go along with Isabella and John, James pressures Catherine to do things she believes are wrong, showing that he has a weaker, less moral character than Catherine.

Henry Tilney (Mr. Tilney)

Henry Tilney is the second son of General Tilney and is Catherine Morland’s love interest. Like Catherine’s father, he works as a parson in a rural community. He is witty, charming, and perceptive, with a much larger frame of reference and experience than Catherine has, but is also sincere and loyal. He is especially concerned for his sister Eleanor’s happiness and welfare. Unlike his father, he is unconcerned with becoming even richer than he is already.

General Tilney

A rich man with many acquaintances, the General is obsessed with his social rank and the wealth of his family. His children all know that he would never want them to marry someone without wealth or high rank. He shows exaggerated kindness to Catherine because he believes her to be rich. The General fixates on home improvement, furniture, and landscaping his property (Northanger Abbey). He is very harsh and even dictatorial with his children, who know that he expects absolute obedience from them.

Eleanor Tilney (Miss Tilney)

A well-mannered, sensible, and sensitive young woman, Eleanor Tilney becomes friends with Catherine in Bath. Eleanor, whose mother died nine years before the action of the novel, suffers from loneliness when she is at home at Northanger Abbey with only her brusque and tyrannical father for company. General Tilney encourages her friendship with Catherine because he believes Catherine to be wealthy and wants her to be Henry’s wife, but Eleanor is very happy to have the company and friendship of another woman.

Mrs. Allen

A very dim-witted, childless woman, Mrs. Allen is a neighbor of the Morlands who invites Catherine to accompany her and her husband to Bath for a holiday. She thinks about nothing but clothing and how much it costs, and remembers very little from most conversations, merely repeating things that those around her say back to them. Supposed to serve as a guardian to Catherine during the trip to Bath, Mrs. Allen is too incapable of independent thought to properly guide Catherine through social situations. She runs into Mrs. Thorpe, a woman she knew fifteen years before at boarding school, which leads to her and Catherine spending much of their time in Bath with the Thorpes.

Mrs. Thorpe

A widow who thinks and talks only about her children, Mrs. Thorpe hopes for her children to marry well. Mrs. Thorpe went to boarding school with Mrs. Allen and knew her to have married a rich man. She believes the Morlands to be wealthy based on their friendship with the Allens.

Mr. & Mrs. Morland

A wife and mother to ten children, Mrs. Morland is not very aware of the dangers of society for a young, inexperienced woman of seventeen. She allows her eldest daughter Catherine to go to Bath with Mrs. Allen, whose character makes her an inadequate chaperone, and never imagines that Catherine might fall in love while there.

A parson in a rural village, Mr. Morland is the father of ten children, including Catherine and James. Although he is not wealthy, he has enough money to make sure all of his children can live comfortably. This level of wealth is a disappointment to both Isabella Thorpe and General Tilney, who believed the Morlands to be wealthy and hoped to hope to raise their own social status by marrying into the Morland family.

Themes

Novels & Their Heroines

From its very first sentence, Northanger Abbey draws attention to the fact that it is a novel, describing its protagonist Catherine Morland as an unlikely heroine. Catherine is “unlikely” because, in most of the novels of the late 18th and early 19th century, heroines were exceptional both in their personalities and in their lives’ circumstances, while Catherine is a rather average young woman. Throughout Northanger Abbey, Austen mocks typical novelistic conventions for their predictability, though never suggesting that this formulaicness makes novels unworthy of being read. Elsewhere in the novel, Austen also upends conventions of the typical courtship novel, especially in the way she describes the deepening relationship between Catherine and Henry.

Jane Austen wrote Northanger Abbey during a period when the popularity of novels had exploded and novel-reading had become an obsession, especially for women. British society was divided on the value of these books and debated novels’ impact on the values and behavior of the women who were their most avid readers.

The most popular works of the second half of the 18th century fell into the related genres of sentimental and Gothic novels. Sentimental novels often portrayed the difficulties faced by a heroine in her pursuit of love and happiness, while Gothic novels placed this same plot into an even more dramatic context, by setting them in spooky old castles during exciting historical times and by including supernatural elements. Many critics condemned such novels as silly, and worried that the dramatic stories of love would influence young women to disobey their families when selecting a spouse. On the other side of the debate, proponents of the novel said that reading about the experiences and emotions of different characters strengthened readers’ ability to feel compassion and act morally in their own lives.

Northanger Abbey sides strongly with the pro-novel side of this debate, but also does not portray the effects of novel-reading in an entirely positive light. In general, the book presents novels as influencing readers to explore the world and seek to understand it, although this sometimes leads to trouble. That trouble, however, can often lead to better self-understanding and a broader understanding of the world.

When Catherine seizes on the wild idea, drawn from novels, that General Tilney murdered his wife nine years earlier, Northanger Abbey is mocking the way that readers of novels can take their dramatic content too much to heart. Yet in this instance, Catherine’s mistaken idea leads her into an embarrassing encounter with Henry, which ultimately teaches her to be a better judge of situations. Although her reading of novels led her into trouble, it also forced her to confront her own ignorance and to grow and mature.

Northanger Abbey is able both to defend and parody novels, in the end, because Northanger Abbey itself is an innovation in the novel form. In the book, Catherine Morland learns that the drama of her real life is no less vivid than the worlds she reads about in novels. This discovery of Catherine’s functions as a kind of turning point for novels themselves, a marker signaling a shift in what constituted a novel. Soon after Austen published Northanger Abbey, novels more generally shifted away from the sentimental works that dominated the eighteenth century to the realist novels that dominated the nineteenth. It was a shift that Jane Austen anticipated.

Sincerity & Hypocrisy

Northanger Abbey describes the experiences of Catherine Morland, a sincere young woman raised in a small, rural parsonage, as she comes into her first sustained contact with the worldly and sometimes hypocritical world of society. Catherine has grown up being told explicitly how others viewed her and her behavior, but those she meets in Bath society sometimes lie about or hide their true opinions to influence or manipulate others. Specifically, Catherine is taken in by the hypocrisy of Isabella Thorpe, who thinks the Morlands are rich and therefore seeks Catherine’s friendship because she hopes to marry Catherine’s brother James. Catherine similarly misunderstands the motives of General Tilney, who seeks to marry his son Henry to Catherine for the same reason. Meanwhile, both Isabella and General Tilney belittle the importance of wealth when in conversation, because they want to hide their motives. Their hypocrisy is eventually unmasked to Catherine once they realize that they were mistaken about the Morlands’ affluence and then change the way they behave towards the Morland brother and sister. But to a reader of the time, these characters’ hypocrisy and their ulterior motive of marrying someone for wealth rather than love would have been clear from the start. Their protestations not to care about money are much too overstated to be believable by anyone with a bit of experience.

While Catherine’s sincerity makes her vulnerable to manipulation by hypocrites, the novel is not simply criticizing such sincerity. In fact, the novel shows how Catherine’s sincerity also earns her the affection and loyalty of true and caring friends. Henry and Eleanor Tilney find Catherine’s sincerity refreshing, a bit comic, and ultimately extremely attractive. For them, her sincerity goes hand in hand with her other fine qualities: loyalty, curiosity, and lack of pretension. In the end, the contrast between Catherine’s sincere love for Henry and Henry’s father’s hypocrisy in courting her only because he believed her to be an heiress convinces Henry that he must stand up to his father and marry Catherine, despite her lower social standing. Through the course of the novel, Catherine learns to better understand when others are not being forthright, but does not cease to be so herself. Although her assumption that others are sincere is a sign of her innocence, her own sincerity is not mere naïveté, but one of her most admirable character traits.

The novel, then, distinguishes between sincerity as naïveté and sincerity as honesty. The happy ending to Catherine’s story, along with the unhappy one to Isabella’s, shows that the novel prizes the latter view—sincerity as honesty. Although Isabella sought to marry to raise her position in the world and Catherine (despite her family’s lack of wealth) had no such intention, Catherine’s sincerity earns her this more comfortable and desirable fate.

Wealth & Respectability

Northanger Abbey, like all of Jane Austen’s novels, looks closely at the role wealth plays in social relationships, especially those between young people considering marrying. For Austen, social rank is not only determined hierarchically, with the wealthiest and those with the highest rank in the aristocracy at the top and all others below. Instead, most of the characters in Northanger Abbey are not aristocrats (with the exception of Eleanor Tilney after she marries a Viscount, much to her status-obsessed father’s excitement), but members of the landed gentry. In Jane Austen’s portrayal of this class, which drew its wealth from the land it owned and rented to tenants, fortune is important, and rich members of the gentry might strive to marry their children to members of the nobility. But these are far from the only factors that determine social status. Instead, true respectability is wrapped up in possessing the quality of genteelness – of being a gentleman or gentlewoman – which is dependent on each individual’s manners.

Northanger Abbey presents a variety of characters who do not understand the importance of good manners to social status and only a few who do understand this distinction and are, therefore, truly genteel. Henry Tilney is more of a gentleman than his father, for example because he is polite and principled, along with being worldly and well-educated.

Northanger Abbey also satirizes a variety of the ways in which people betray their obsession with money. Some characters fixate on a certain category of material possessions and find themselves unable to talk about anything else, however much they bore their listeners. John Thorpe’s intense interest in horses and carriages, Mrs. Allen’s interest in clothes, and General Tilney’s interest in home improvement all betray their fixation on money and what it can buy, while also making them seem a bit ridiculous. A true gentleman or gentlewoman would show a better sense of what social situations called for and would exercise restraint in expressing themselves.

Another way of parodying the obsession with money is by displaying the lengths that characters will go to hide this obsession. Both Isabella Thorpe and General Tilney claim to care nothing about money, when it is in fact the only thing they truly care about. Eventually, when they realize that the Morlands are not as rich as they had believed, their behavior towards the Morlands changes and their hypocrisy is unmasked.

General Tilney’s terrible treatment of Catherine once he realizes she is not rich proves that he is not actually respectable. As Mrs. Moreland says upon Catherine’s return, General Tilney “had acted neither honourably nor feelingly – neither as a gentleman nor as a parent.” Even today, to send a teenager like Catherine home alone without making sure she had money and without consulting her parents would be considered both unkind and inappropriate. At a time when the protection of young women was so much more of a concern to all, General Tilney’s action showed disrespect for the social codes that governed relationships. This action was not only rude, it was beyond the pale and put his status as a “gentleman” into doubt.

At the same time Northanger Abbey does not discount the importance of money. It is a sign of Catherine’s naïveté that she does not see through the hypocrisy of Isabella, John, and General Tilney, who all say that they care little for money. Because, as any person familiar with the world should know, of course they must care about money at least to some extent. Money is important! Catherine’s own happy ending attests as much. That Henry returns her love is wonderful, but just as excellent is the fact that marrying Henry will bring Catherine much more wealth than she or her family ever thought possible, and the comfort and security provided by that wealth.

Experience & Innocence

Like most of Jane Austen’s novels, Northanger Abbey is concerned with whether a young person will mature into a good judge of character. Some well-meaning adults in Northanger Abbey have blind spots that keep them from being objective judges of character, while other adults are manipulative, cruel, and hypocritical. As she navigates relationships with these different types of people, the pressing question for the young protagonist Catherine Morland is whether, in growing up and moving from innocence to experience, she will become wise. This wisdom is tied to being judicious about whom to trust.

Catherine is principled and strong-willed, but also aware that her lack of experience makes her unable to judge how to behave in every circumstance. She wants always to act with propriety, especially when it comes to acting modestly and appropriately when interacting with men, and hopes to rely on the advice of others.

At the beginning of the novel, Catherine does not realize that she cannot trust every older and more experienced person to guide her. This is perhaps because Catherine is one of ten children, and her own mother has been so preoccupied with raising young children that “her elder daughters were left to shift for themselves” without much in the way of advice about how best to behave as they began their lives as adult women. As we see at the novel’s conclusion, when Mrs. Morland fails to suspect that Catherine is suffering from heartache, Mrs. Morland is an example of a woman who, despite having ten children, has never lost her innocence about the world. She is a good woman, but not a wise one. It is likely because of Mrs. Morland’s innocence that at the beginning of the novel she allows Catherine to go to Bath under the care of Mrs. Allen, an adult without the wisdom to help Catherine navigate Bath society.

Catherine also assumes that no one she knows would choose to take an unkind, immoral, or inappropriate action on purpose. When Isabella does something improper, Catherine assumes that she is only doing the wrong thing out of ignorance of what the right thing is. She does not understand that part of growing into adulthood is having to make one’s own choices, wrong or right, and stand by them, and she often wants to intervene to let someone know that they are acting badly.

As Catherine gains experience, she also learns the importance of thinking for herself. When Catherine meets the unpleasant, rude boor John Thorpe and the domineering General Tilney, she assumes at first that her negative judgments of them are mistaken. It takes her time and a great deal of evidence to realize that John Thorpe, despite being her brother’s friend, is a liar and an unpleasant companion. As she tries to make sense of her impressions of General Tilney, Catherine takes a different tact. She relies on the knowledge she has gained from books rather than knowledge she has gained from life and imagines General Tilney to be a horrible criminal, rather than just manipulative and wealth-obsessed.

Catherine is embarrassed when Henry discovers what she had been imagining his father to have done, and realizes how farfetched it was to assume that General Tilney was similar to a villain in a gothic novel just because she does not like him. But at the same time, she is growing to trust her own judgment. She realizes that she was not entirely wrong about the General, that although he is not a murderer, he may have major character flaws, and that in all people “in their hearts and habits, there was a general though unequal mixture of good and bad.” In the end, when Catherine learns that the General drove her from his house because he realized she was not an heiress, she decides that “in suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty.” Although this is an exaggeration, it shows that Catherine has come to feel confidence in her own judgment.

In a future not described in the novel, it seems reasonable to think that Catherine will be more confident in her judgment and more reasonable in the judgments she makes. She has gained experience of the untrustworthy from her encounters with the Thorpes and General Tilney, and learned also that she was right to place her trust in the good character of Henry and Eleanor Tilney. Overall, then, Northanger Abbey shows that, although experience does not always bring wisdom, if a young and innocent person pays attention to her surroundings and the lessons that experience teaches, she can mature into a person with good judgment that guides her to place her trust with those who deserve it.

Loyalty & Love

Northanger Abbey is a courtship novel that goes against certain important conventions of “courtship novels,” especially to make the point that loyalty is the surest sign of true love. In most of the sentimental novels written during the time when Austen was working on Northanger Abbey, the heroine is exceptionally beautiful and the hero is head over heels in love with her. In Northanger Abbey, on the other hand, the roles are reversed. Catherine is attracted to Henry, and it is her obvious love for him, rather than his admiration of her, that binds him to her. Even once he feels affection and commitment to her, he still recognizes that his feelings for her did not originate as a deep attraction to her, but that “a persuasion of her partiality for him had been the only cause of giving her a serious thought.” Indeed, it is only when his loyalty to Catherine is put to the test by his father’s command that he forget about her that Henry decides that he loves her. Henry’s sense that he would be acting disloyally by following his father’s command serves to cement his affection for Catherine.

The central importance of loyalty to love is also emphasized in the novel’s portrayal of a false love. In the novel’s other central relationship, Isabella Thorpe’s disloyalty to James Morland in flirting with Frederick Tilney betrays both her lack of true feeling for James and the fact that she is more concerned with marrying someone wealthy than with marrying someone she loves.

When Catherine is distressed by the flirtation between Frederick Tilney and Isabella (who is by this point James’s fiancée) and asks Henry to tell his brother to leave Bath, Henry’s refusal to interfere with his brother is also a testimonial to the importance of loyalty to relationships. Henry explains that any interference on his part would not benefit James, because for Isabella’s love to be worth anything she must be loyal to the man she loves without regard to the other men she meets. Similarly, the General’s interference between Henry and Catherine only strengthens their resolve to be together. An essential part of love between spouses or prospective spouses is a refusal to let any third person come between them.

Northanger Abbey portrays courting couples as needing to have their loyalty to one another tested before a relationship can be said to have a solid basis for marriage, but it also makes a larger point about the nature of love itself. In many of the conventional novels that Austen parodies, love is an almost magical state of emotional attachment and physical attraction. In Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney states that marriage is a contract in which the two spouses must work to be agreeable to one another and keep each other from ever regretting having married. Austen makes the case that for a marriage to work, there should be a conscious decision to enter into a contract and abide by it.

Symbols

Northanger Abbey (the building)

Northanger Abbey parodies the gothic novels that Catherine Morland reads avidly, many of which are set in old buildings like castles and abbeys. Catherine, influenced by her gothic novels, hopes to have an adventure exploring one of these mysterious old buildings. But instead of involving herself in a thrilling narrative, Catherine’s interactions with these old buildings (most notable Northanger Abbey itself) force her to get to know her own character and to improve her own capacity to judge situations independently. The pursuit of self-knowledge and personal happiness, the novel suggests, can be just as dramatic and difficult as the pursuit of the mysterious, supernatural, or criminal. Similarly, the novel suggests that a person’s own self is like an old building, full of nooks and crannies and secrets that must be explored to be understood.

Clothing

Northanger Abbey presents clothing as one of the things that shallow or status-obsessed people fixate on. It is a sign of bad taste to think only of what one wears like Mrs. Allen does, or to dress flashily as Isabella Thorpe does. That said, Northanger Abbey is by no means anti-fashion. Instead, dressing well and elegantly, like Eleanor Tilney, and taking an interest in the economics of clothing, as Henry Tilney does, show worldliness and good taste.

The Written Word

Letters, journals, and books represent knowledge. Catherine is an avid reader, but when Henry mentions her journal, she has little use for such habits. Information about Isabella’s engagement to James, as well as John’s interest in Catherine, comes via letter. The book at the pump-room is a regular source of information, providing information on attendees. Catherine’s attempt to learn about Henry leads her to consult the “pump-room book” initially, even though “his name was not in the pump-room book, and curiosity could do no more” (Chapter 5).

Unlike John, Henry is an avowed reader, as he reveals during discussions with Catherine and Eleanor. He notes, “The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure” (Chapter 14).

However, the written word is not always a reliable source of information. The papers found in the cabinet in Catherine’s room at Northanger Abbey are a false source of intrigue. “Impatient to get rid of those hateful evidences of her folly, those detestable papers then scattered over the bed, she rose directly, and folding them up as nearly as possible in the same shape as before, returned them to the same spot within the cabinet, with a very hearty wish that no untoward accident might ever bring them forward again, to disgrace her even with herself” (Chapter 22).

Gothic Novels

The Mysteries of Udolpho is symbolic of Gothic novels as a whole. Ann Radcliffe’s novel is not the only Gothic novel that is cited in Northanger Abbey, but it is the most frequent example—with 18 references by name. All of those references occur prior to Catherine’s trip to Northanger Abbey. Catherine is smitten with the book: “While I have Udolpho to read, I feel as if nobody could make me miserable. Oh! The dreadful black veil!” (Chapter 6).

This novel represents not just Gothic novels but novels in general. Catherine uses the novel, consciously or not, to assess people. John Thorpe has not read it: “Udolpho! Oh, Lord! Not I; I never read novels; I have something else to do” (Chapter 7). However, Isabella, Eleanor, and Henry all have read it.

She also uses it as her example of the sort of adventure she expects at an abbey, as well as when invited to visit the castle. “On the other hand, the delight of exploring an edifice like Udolpho, as her fancy represented Blaize Castle to be, was such a counterpoise of good as might console her for almost anything” (Chapter 11).

Carriages

Carriages, including their quality and speed and handling, are symbolic of character and of social status. John rides with an attitude akin to his boastful personality. “Curricle-hung, you see; seat, trunk, sword-case, splashing-board, lamps, silver moulding, all you see complete; the iron-work as good as new, or better. He asked 50 guineas; I closed with him directly, threw down the money, and the carriage was mine” (Chapter 7). He uses the traits of it, as well as his buying it, to express that he is successful and bold.

Mrs. Allen points out there are moral issues to going out in carriages. “Young men and women driving about the country in open carriages! Now and then it is very well; but going to inns and public places together! It is not right; and I wonder Mrs. Thorpe should allow it” (Chapter 13).

Henry handles his carriage calmly and steadily, again reflecting his persona. The general keeps carriages that reveal his wealth. When traveling to Northanger Abbey, the general has a “fashionable chaise and four—postilions handsomely liveried, rising so regularly in their stirrups, and numerous outriders properly mounted” (Chapter 20).

At the end of her stay at the abbey, Catherine, who is not actually wealthy despite the general’s prior theories, is dismissed in a hired carriage.

Bildungsroman

Northanger Abbey fits into the tradition of coming-of-age novels (bildungsroman, a German word for a novel of growth and development). Catherine is on a journey of maturation. She literally journeys from her parents’ home to the city of Bath where she enters into society under the somewhat casual watch of Mr. and Mrs. Allen. With no guidance offered to her, Catherine navigates society as best she can. Mrs. Allen has provided assistance with dress and lodging, but she does not oversee Catherine’s every move. Catherine’s trust in Isabella gives her a misapprehension of the rules of society. This lack of oversight allows Catherine to make missteps in her interactions with both the Thorpes and the Tilneys. When she requests guidance from the Allens, Catherine learns that going about with John Thorpe, as Isabella has encouraged, is improper. When Catherine takes the next journey to Northanger Abbey, she is again without female guidance beyond a young companion. In this case, however, Catherine’s companion is Eleanor Tilney. Unlike Isabella, Eleanor is not deceitful. She is without agency, though—controlled as she is by General Tilney. This is most obvious when the general’s attitude shift toward Catherine provokes the third stage of her journey: she travels on her own in a hired carriage 70 miles to her parents’ home.

The physical journeys coincide with a growing awareness of other characters’ flaws and foibles, as well as of her own. Catherine’s journey is temporarily on hold when she is at her mother’s house after the general sends her away, but Henry Tilney arrives to ask her to marry him. The novel closes with the narrator summing up months of time with the revelation that they corresponded and eventually wed. Catherine’s evolution from innocent girl to questioning young woman culminates in a wedding. She has entered into a “good match” with a man who cares for her, and in the process of reaching that point, she has taken several long trips on which she has developed as a person.

Modern Interpretations of Northanger Abbey

If you type Jane Austen into Amazon, you will be met with pages of different editions of Jane’s novels. You will also be met by a wide range of modern novels inspired by Jane and her characters. By the year 2000, it was estimated that there were over 100 printed adaptations of her work, ranging from sequels to erotica to horror stories. Most of the spin-offs inspired by Austen’s novels stem from Pride and Prejudice.

Northanger Abbey was last adapted by the BBC in 2007.

The same period of Austen’s life when she would have started Northanger Abbey was chronicled in the film Becoming Jane.

Another film, Austenland, follows the plot of Northanger Abbey. Except instead of losing her view of reality to that of Gothic novels, the heroine (aptly named Jane) has an obsession with the world of Austen’s novels.

As part of The Austen Project, internationally-renowned Scottish crime writer Val McDermid adapted Northanger Abbey as novel set in modern times.

Study Guides:

Lit Charts by Sparknotes: Northanger-Abbey-LitChart (PDF)

Question

- What makes Austen’s work popular and important still today?