35

A Brief History of Feminism

Before we can dive into the meaning of intersectionality, we must first look at the larger idea that birthed it: feminism. According to Encylopedia Britannica, feminism is “the belief in social, economic, and political equality of the sexes.” That’s it! There are many connotations of what the word feminism means, especially in a society as diverse as America, but it’s a belief grounded in gender equality. While there have been people fighting for gender equality (and human equality in general) throughout history, feminism is most famous for creating the women’s rights movements, which advocated for issues like women’s suffrage and equal pay.

These various waves of feminism are interwoven into women’s rights, civil rights, and social justice movements. What has especially characterized these movements is the championing of equality under the law and within our socioeconomic structures. That said, the differences and the existing tension among these various waves outlines an important question: What kind of equality does feminism seek? The waves of feminism are not a linear progression and consensus of progress, even though they roughly follow a linear timeline. Instead, they are intense changes of perspective among different generations of women.

The first wave: 1848 to 1920

First wave feminism during the late 19th century is primarily characterized by the women’s suffrage movement and their championing of the woman’s right to vote. While many continue to celebrate feminist leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the women’s suffrage movement largely excluded and discriminated against women of color including suffragettes such as Ida B. Wells, Ellen Watkins Harper and Sojourner Truth. White women were eventually guaranteed the right to vote in 1920 under the 19th amendment. Women of color wouldn’t have the universal right to vote until 45 years later with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, when all people of color were guaranteed the right to vote.

The second wave: 1963 to the 1980s

Second wave feminism, from roughly the 1960s to the 1990s, encompassed far more issues such as pay equality, reproductive rights, female sexuality, and domestic violence. Like the first wave of feminism, many of these goals were achieved through legislation and important court decisions. That said, while the second wave movement made some attempts to encompass racial justice, it remained a lesser priority than gender. Class and race were viewed as secondary issues, if they were considered at all. The disparities between white women and white men narrowed, but the inequity between women of color and white men or even between women of color and white women largely remained the same.

The third wave: 1991(?) to ????

Third wave feminism emerged from the mid 1990’s, challenging female heteronormativity. Third wavers sought to redefine femininity and sought to celebrate differences across race, class, and sexual orientations. While third wave feminists support feminism, they reject many stereotypes of the feminine ideal, sometimes even rejecting the word “feminism” itself. This movement was a stark departure from the second wave and the development of intersectionality began to take form. The term intersectionality was coined by lawyer and activist Kimberlé Crenshaw “to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics ‘intersect’ with one another and overlap.”

The present day: a fourth wave?

Fourth wave feminism is newly emerging over the last decade or so, therefore it’s difficult to define. That said, fourth wave feminism is seen as characterized by action-based viral campaigns, protests, and movements like #MeToo advancing from the fringes of society into the headlines of our everyday news. The fourth wave has also been characterized as “queer, sex-positive, trans-inclusive, body-positive, and digitally driven.” It seeks to further deconstruct gender norms. The problem these feminists confront is systemic white male supremacy. Fourth wavers believe there is no feminism without an understanding of comprehensive justice that deconstructs systems of power and includes emphasis on racial justice as well as examinations of class, disability, and other issues.

None of these movements are monoliths, but the tension between the different versions of feminism is quite prominent. While the arguments about the various incarnations of feminism continue, we should consider what feminism means in conjunction to equality for all.

Intersectionality Explained

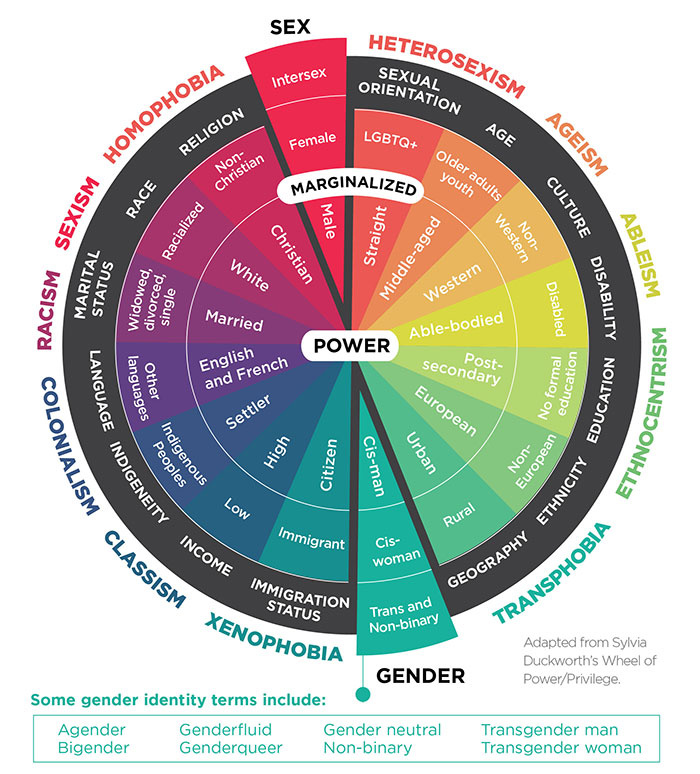

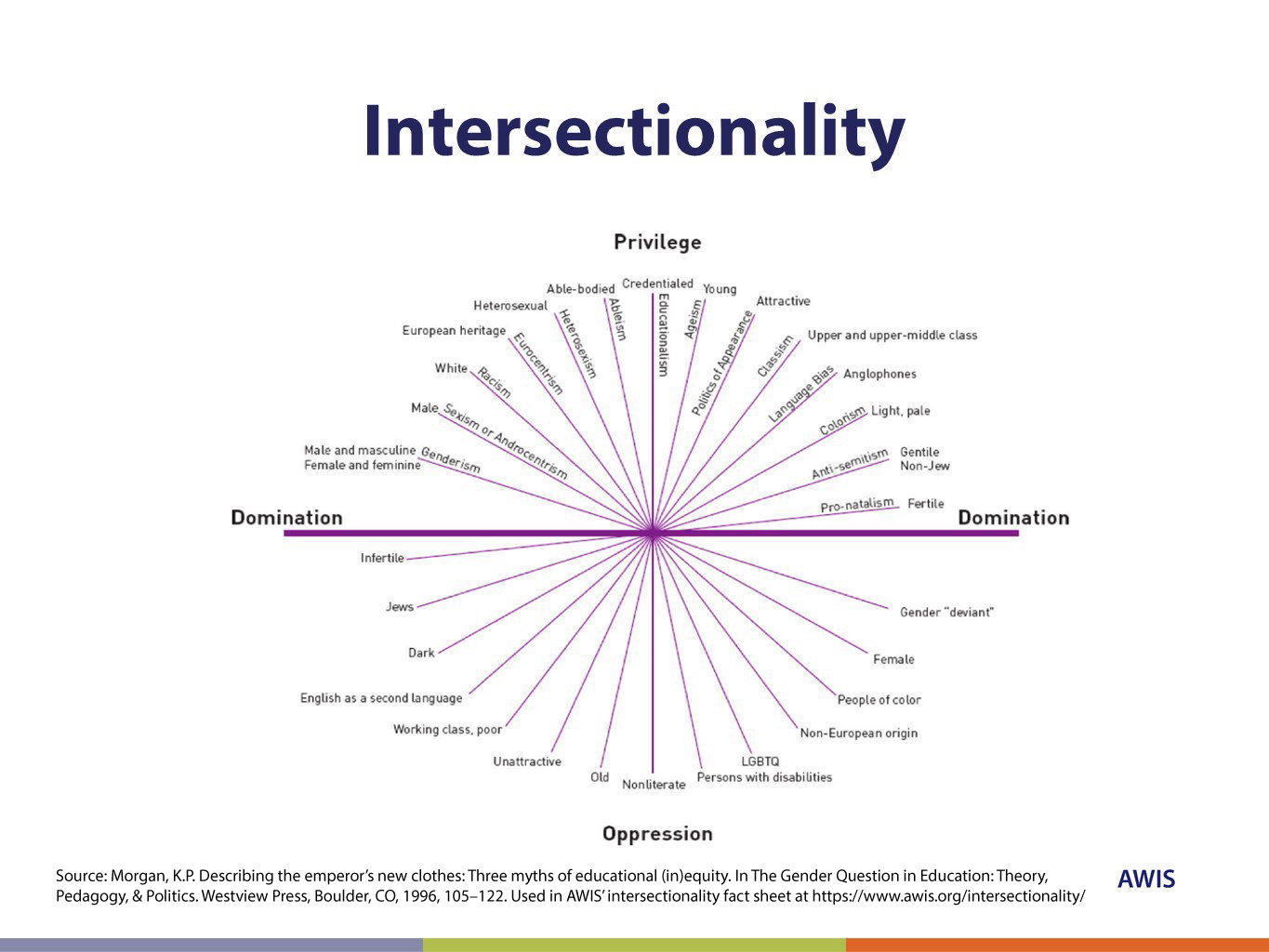

The term intersectionality can be defined as “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.”

“Intersectional feminism” is much more than the latest feminist buzzword. It is a decades-old term many feminists use to explain how the feminist movement can be more diverse and inclusive. If feminism is advocating for women’s rights and equality between the sexes, intersectional feminism is the understanding of how women’s overlapping identities — including race, class, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation — impact the way they experience oppression and discrimination.

A white woman is penalized by her gender but has the advantage of race. A black woman is disadvantaged by her gender and her race. A Latina lesbian experiences discrimination because of her ethnicity, her gender, and her sexual orientation.

The term makes some people uncomfortable in part because it suggests that white women recognize their privilege and examine the ways in which that privilege can make other women invisible within the feminist movement.

The History of Intersectionality

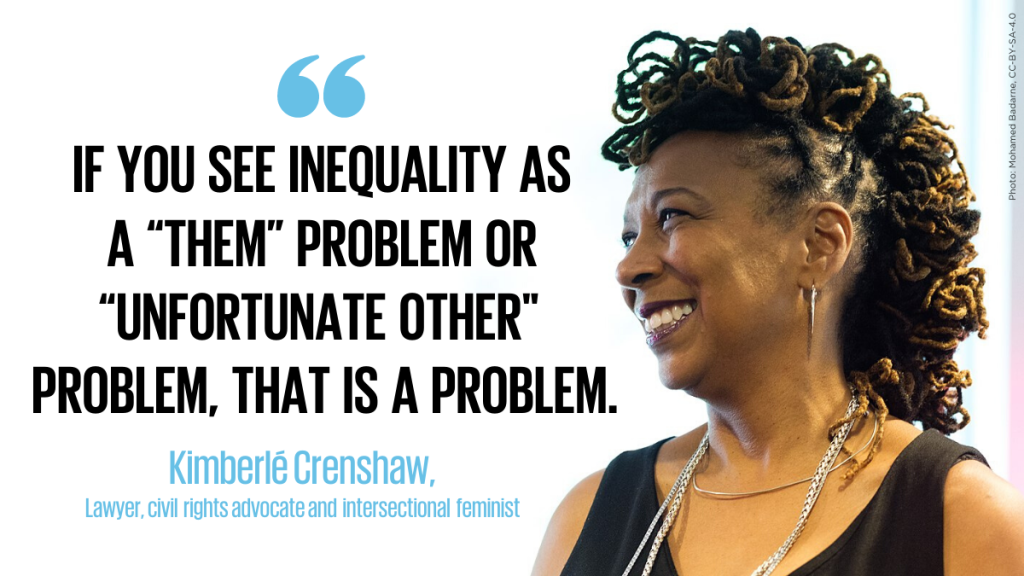

The term “intersectionality” was coined 30 years ago by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a professor at both Columbia and the University of California Los Angeles who specializes in civil rights, race, and racism.

To understand what intersectionality is, and what it has become, you have to look at Crenshaw’s body of work over the past 30 years on race and civil rights. A graduate of Cornell University, Harvard University, and the University of Wisconsin, Crenshaw has focused in much of her research on the concept of critical race theory.

As she detailed in an article written for the Baffler in 2017, critical race theory emerged in the 1980s and ’90s among a group of legal scholars in response to what seemed to Crenshaw and her colleagues like a false consensus: that discrimination and racism in the law were irrational, and “that once the irrational distortions of bias were removed, the underlying legal and socioeconomic order would revert to a neutral, benign state of impersonally apportioned justice.”

This was, she argued, a delusion as comforting as it was dangerous. Crenshaw didn’t believe racism ceased to exist in 1965 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, nor that racism was a mere multi-century aberration that, once corrected through legislative action, would no longer impact the law or the people who rely upon it.

There was no “rational” explanation for the racial wealth gap that existed in 1982 and persists today, or for minority underrepresentation in spaces that were purportedly based on “colorblind” standards. Rather, as Crenshaw wrote, discrimination remains because of the “stubborn endurance of the structures of white dominance” — in other words, the American legal and socioeconomic order was largely built on racism.

Before the arguments raised by the originators of critical race theory, there wasn’t much criticism describing the way structures of law and society could be intrinsically racist, rather than simply distorted by racism while otherwise untainted with its stain. So there weren’t many tools for understanding how race worked in those institutions.

That brings us to the concept of intersectionality, which emerged from the ideas debated in critical race theory. Crenshaw first publicly laid out her theory of intersectionality in 1989, when she published a paper in the University of Chicago Legal Forum titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex.” You can read that paper here.

The paper centers on three legal cases that dealt with the issues of both racial discrimination and sex discrimination: DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, Moore v. Hughes Helicopter, Inc., and Payne v. Travenol. In each case, Crenshaw argued that the court’s narrow view of discrimination was a prime example of the “conceptual limitations of … single-issue analyses” regarding how the law considers both racism and sexism. In other words, the law seemed to forget that black women are both black and female, and thus subject to discrimination on the basis of both race, gender, and often, a combination of the two.

For example, DeGraffenreid v. General Motors was a 1976 case in which five black women sued General Motors for a seniority policy that they argued targeted black women exclusively. Basically, the company simply did not hire black women before 1964, meaning that when seniority-based layoffs arrived during an early 1970s recession, all the black women hired after 1964 were subsequently laid off. A policy like that didn’t fall under just gender or just race discrimination. But the court decided that efforts to bind together both racial discrimination and sex discrimination claims — rather than sue on the basis of each separately — would be unworkable.

As Crenshaw details, in May 1976, Judge Harris Wangelin ruled against the plaintiffs, writing in part that “black women” could not be considered a separate, protected class within the law, or else it would risk opening a “Pandora’s box” of minorities who would demand to be heard in the law:

“The legislative history surrounding Title VII does not indicate that the goal of the statute was to create a new classification of ‘black women’ who would have greater standing than, for example, a black male. The prospect of the creation of new classes of protected minorities, governed only by the mathematical principles of permutation and combination, clearly raises the prospect of opening the hackneyed Pandora’s box.”

Crenshaw argues in her paper that by treating black women as purely women or purely black, the courts, as they did in 1976, have repeatedly ignored specific challenges that face black women as a group.

“Intersectionality was a prism to bring to light dynamics within discrimination law that weren’t being appreciated by the courts,” Crenshaw said. “In particular, courts seem to think that race discrimination was what happened to all black people across gender and sex discrimination was what happened to all women, and if that is your framework, of course, what happens to black women and other women of color is going to be difficult to see.”

But then something unexpected happened. Crenshaw’s theory went mainstream, arriving in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015 and gaining widespread attention during the 2017 Women’s March, an event whose organizers noted how women’s “intersecting identities” meant that they were “impacted by a multitude of social justice and human rights issues.” As Crenshaw told me, laughing, “the thing that’s kind of ironic about intersectionality is that it had to leave town” — the world of the law — “in order to get famous.”

She compared the experience of seeing other people talking about intersectionality to an “out-of-body experience,” telling me, “Sometimes I’ve read things that say, ‘Intersectionality, blah, blah, blah,’ and then I’d wonder, ‘Oh, I wonder whose intersectionality that is,’ and then I’d see me cited, and I was like, ‘I’ve never written that. I’ve never said that. That is just not how I think about intersectionality.’”

She added, “What was puzzling is that usually with ideas that people take seriously, they actually try to master them, or at least try to read the sources that they are citing for the proposition. Often, that doesn’t happen with intersectionality, and there are any number of theories as to why that’s the case, but what many people have heard or know about intersectionality comes more from what people say than what they’ve actually encountered themselves.”

The current debate over intersectionality is really three debates: one based on what academics like Crenshaw actually mean by the term, one based on how activists seeking to eliminate disparities between groups have interpreted the term, and a third on how some conservatives are responding to its use by those activists.

Intersectionality operates as both the observance and analysis of power imbalances, and the tool by which those power imbalances could be eliminated altogether. And the observance of power imbalances, as is so frequently true, is far less controversial than the tool that could eliminate them.

What is Intersectional Feminism?

Most know that feminism is the movement set on achieving gender equality. But not as many know what intersectional feminism is. So what is it, exactly?By adding the idea of intersectionality to feminism, the movement becomes truly inclusive and allows women of all races, economic standings, religions, identities, and orientations for their voices to be heard.

Over the course of its existence, feminism has mainly focused on the issues experienced by white, middle-class women. For example, it is largely shared and advertised that a woman makes 78 cents to a man’s dollar. But this is only the statistic for white women. As upsetting as it is, women of minority groups make even less. Black women earn 64 cents to white men’s dollar and Hispanic women only earn 56 cents. Intersectional feminism takes into account the many different ways each woman experiences discrimination. “White feminism” is a term that is used to describe a type of feminism that overshadows the struggles women of color, LGBTQ women and women of other minority groups face. So, essentially, it’s not true feminism at all.

“White feminism” ignores intersectionality and neglects to recognize the discriminations experienced by women who are not white. It’s important to note that not all feminists who are white practice “white feminism.” “White feminism” depicts the way white women face gender inequality as the way all women experience gender inequality, which just isn’t correct.

The key to combating “white feminism” is education about intersectionality. Crenshaw defines intersectionality as “The idea that we experience life, sometimes discrimination, sometimes benefits, based on a number of identities.” She first started to develop her theory on intersectionality when she studied the ways black women are discriminated against for both their gender and race. She comments, “The basic term came out of a case where I was looking at black women who were being discriminated against, not just as black people and not just as women, but as black women. So, intersectionality was basically just a metaphor to say they are facing race discrimination from one direction. They have gender discrimination from another direction, and they’re colliding in their lives in ways we really don’t anticipate and understand.”

Intersectionality is a term used to describe how different factors of discrimination can meet at an intersection and can affect someone’s life. Adding intersectionality to feminism is important to the movement because it allows the fight for gender equality to become inclusive. Using intersectionality allows us all to understand each other a little bit better.

At the end of the day, we might all experience discrimination and gender inequality differently and uniquely, but we are all united in our hope for equality.

Why Intersectionality Matters

From the disparate impacts of the COVID-19 crisis in communities around the globe to international protests against racism and discrimination, current events have shown that we are far from achieving equality. Trying to interpret and battle a multitude of injustices right now may feel overwhelming. How do we take on all these issues, and why should we? Intersectional feminism offers a lens through which we can better understand one another and strive towards a more just future for all.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American law professor who coined the term in 1989 explained Intersectional feminism as, “a prism for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other,” in a recent interview with Time.

“All inequality is not created equal,” she says. An intersectional approach shows the way that people’s social identities can overlap, creating compounding experiences of discrimination.

“We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts,” Crenshaw said.

Intersectional feminism centers the voices of those experiencing overlapping, concurrent forms of oppression in order to understand the depths of the inequalities and the relationships among them in any given context.

In Brazil, Valdecir Nascimento, a prominent women’s rights activist, says that “The dialogue to advance black women’s rights should put them in the center.” For 40 years, Nascimento has been fighting for equal rights, “Black women from Brazil have never stopped fighting,” she says, noting that black women were part of the feminist movement, the black movement, and other progressive movements. “We don’t want others to speak for black feminists—neither white feminists nor black men. It’s necessary for young black women to take on this fight. We are the solution in Brazil, not the problem,” she says.

Using an intersectional lens also means recognizing the historical contexts surrounding an issue. Long histories of violence and systematic discrimination have created deep inequities that disadvantage some from the outset. These inequalities intersect with each other, for example, poverty, caste systems, racism, and sexism, denying people their rights and equal opportunities. The impacts extend across generations.

Sonia Maribel Sontay Herrera is an indigenous woman and human rights defender from Guatemala where systematic discrimination against indigenous women has gone on for decades. Herrera has felt the consequences of these historical injustices since she was a girl.

At ten years old, she moved to a city to attend school, an opportunity most indigenous girls don’t get, she says. However, Herrera was forced to abandon her native language, K’iche’, and learn in Spanish, which she experienced as an unjust burden for an indigenous woman, since it was the language of the colonizer. After finishing her studies, as Herrera searched for professional work, she immediately encountered racism and sexist stereotypes. Since she was an indigenous woman, some said that they only had work for her in the home.

“They see us as domestic workers; when they see an indigenous woman, they assume that’s all we can do,” she explains, outlining the ways in which she experiences compounding forms of discrimination based on her identity.

“Those who are most impacted by gender-based violence, and by gender inequalities, are also the most impoverished and marginalized—black and brown women, indigenous women, women in rural areas, young girls, girls living with disabilities, trans youth and gender non-conforming youth,” explains Majandra Rodriguez Acha, a youth leader and climate justice advocate from Lima, Peru. That marginalized communities are the most impacted by natural disasters and the devastating effects of climate change is not a mere coincidence, she stresses.

While issues ranging from discrimination based on gender identity to disparate environmental burdens may seem separate at first, intersectional feminism illuminates the connections between all fights for justice and liberation. It shows us that fighting for equality means not only turning the tables on gender injustices, but rooting out all forms of oppression. It serves as a framework through which to build inclusive, robust movements that work to solve overlapping forms of discrimination, simultaneously.

As concurrent, ongoing crises unfold across the globe today, we can use an intersectional feminist lens to understand their linkages and build back better.

Intersectional feminism matters today because:

The impacts of crises are not uniform.

Countries and communities around the world are facing multiple, compounding threats. While the sets of issues vary from place to place, they share the effect of magnifying pre-existing needs such as housing, food, education, care, employment, and protection.

Yet crises responses often fail to protect the most vulnerable. “If you are invisible in everyday life, your needs will not be thought of, let alone addressed, in a crisis situation,” says Matcha Porn-In, a lesbian feminist human-rights defender from Thailand who works to address the unique needs of LGBTIQ+ people, many of whom are indigenous, in crisis settings.

In the context of the coronavirus pandemic, the challenges of the virus have exacerbated long-standing inequities and decades of discriminatory practices, leading to unequal trajectories.

Rather than fragmenting our fights, taking on board the experiences and challenges faced by different groups has a unifying effect; we are better able to understand the issues at hand and, therefore, find solutions that work for all.

Injustices must not go unnamed or unchallenged.

Looking through an intersectional feminist lens, we see how different communities are battling various, interconnected issues, all at once. Standing in solidarity with one another, questioning power structures, and speaking out against the root causes of inequalities are critical actions for building a future that leaves no one behind.

“If you see inequality as a “them” problem or “unfortunate other” problem, that is a problem,” says Crenshaw. “We’ve got to be open to looking at all of the ways our systems reproduce these inequalities, and that includes the privileges as well as the harms.”

A new ‘normal’ must be fair for all.

Because crises lay bare the structural inequalities that shape our lives, they are also moments of big resets – catalysts for rebuilding societies that offer justice and safety to everyone. They provide a chance to redefine ‘normal’ rather than return to business as usual.

Taking an intersectional feminist approach to the crises of today helps us seize the opportunity to build back better, stronger, resilient, and equal societies.

“COVID-19 has presented us… with a rare opportunity,” says Silliniu Lina Chang, President of the Samoa Victim Support Group, who has been advocating for improved services for victims of domestic violence during the pandemic. “[It is] a time for all of us to reset. Think outside of our comfort zone and look beyond to the neighbour that is in need.”

Intersectionality in Practice

YouTube stars Laci Green and Franchesca Ramsey explain that intersectional feminism is integral to the larger movement because it looks at all women’s issues — not just the some.

“From its wee beginnings, the feminist movement has focused mostly on the issues of middle-class white ladies,” Green points out. And intersectional feminism includes “basically every woman that mainstream feminism has a bad habit of leaving behind.”

Like these women:

“How can a movement for women really be effective without addressing the needs of all women?” Ramsey asks. Well, it can’t. That’s why Green and Ramsey put together a quick list of suggestions that make intersectional feminism easy to implement:

“Privileges are places where we hold more power in society than others,” Green explains. “For example, I’m white, I’m cis-gender, I’m able-bodied, I have a roof over my head and food on the table. These are privileges that not every woman has and that shapes my experience of the world.”

By examining these privileges and listening to one another we can all practice intersectional feminism. And if you’re still confused, Green says: “Strip away all the fancy language and all we’re really talking about is looking out for each other.”

“On the feminist issues where we hold privilege, it’s crucial to listen to women who don’t. To listen to their experiences, to see the world through a more complex lens and to raise the voices of those who have less power,” Green explained. Ramsey added, “You can’t exactly walk the walk if you have no idea where the walk even goes.” Despite how daunting and intimidating the term intersectionality may seem, it’s just about us standing up and looking out for each other.

Case Study:

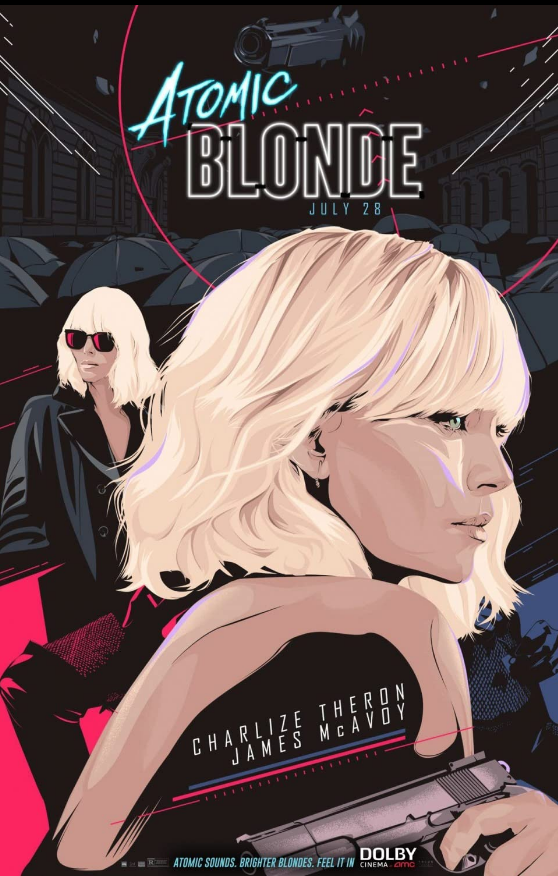

Atomic Blonde

Synopsis

Beyond Atomic Blonde: cinema’s long, proud history of violent women

Atomic Blonde in Comics

Atomic Blonde on Film:

Focus Features, 2017