33

Media play important roles in society. They report on current events, provide frameworks for interpretation, mobilize citizens with regard to various issues, reproduce predominant culture and society, and entertain (Llanos and Nina, 2011). As such, the media can be an important actor in the promotion of gender equality, both within the working environment (in terms of employment and promotion of female staff at all levels) and in the representation of women and men (in terms of fair gender portrayal and the use of neutral and non-gender specific language).

Gender in Media: Myths & Facts

MYTH: Boys and girls are equally represented in film and television.

FACT: Even among the top-grossing G-rated family films, girl characters are out numbered by boys three-to-one.

That’s the same ratio that has existed since the end of World War II. For decades, male characters have dominated nearly three-quarters of speaking parts in children’s entertainment, and 83% of film and TV narrators are male. The Institute’s research indicates that in some group scenes, only 17% of the characters are female. These absences are unquestionably felt by audiences, and children learn to accept the stereotypes represented. What they see affects their attitudes toward male and female values in our society, and the tendency for repeated viewing results in negative gender stereotypes imprinting over and over.

MYTH: Family entertainment is a safe haven for female characters.

FACT: Astoundingly, even female characters in family films serve primarily as “eye candy.”

Female characters continue to show dramatically more skin than their male counterparts, and feature extremely tiny waists and other exaggerated body characteristics. This hypersexualization and objectification of female characters leads to unrealistic body ideals in very young children, cementing and often reinforcing negative body images and perceptions during the formative years. Research shows that lookism still pervades cinematic content in very meaningful ways.

MYTH: Things are looking great for females behind the camera.

FACT: Females behind the camera fall far behind their male contemporaries and are at a distinct disadvantage in the entertainment industry.

Only 7% of directors, 13% of writers, and 20% of producers are female. With such a dearth of female representation in front of and behind the camera, it’s a struggle to champion female stories and voices. The Institute’s research proves that female involvement in the creative process is imperative for creating greater gender balance before production even begins. There is a causal relationship between positive female portrayals and female content creators involved in production. In fact, when even one woman writer works on a film, there is a 10.4% difference in screen time for female characters. Sadly, men outnumber women in key production roles by nearly 5 to 1.

MYTH: Girls on screen compare favorably to their male counterparts.

FACT: Messages that devalue and diminish female characters are still rampant in family films.

Gender stereotyping is an inherent problem in today’s entertainment landscape, and children are the most vulnerable recipients of depictions that send the message that girls are less valuable and capable than boys. The Institute’s research illustrates that female characters who are lucky enough to garner speaking roles tend to be highly stereotyped. From 2006 to 2009 not one female character was depicted in G-rated family films in the field of medical science, as a business leader, in the law, or in politics. 80.5% of all working characters are male and 19.5% are female, which is a contrast to real-world statistics of women comprising 50% of the workforce. With repeated viewings, young audiences may fail to realize this lopsided view is not, in fact, reality and believe there is no need for gender parity or industry change. Today’s children will be our future business leaders, content creators and parents and the ones who need to lead the charge for future generations.

MYTH: Gender imbalance issues have gotten better over time.

FACT: Statistically, there has been little forward movement for girls in media in six decades.

For nearly 60 years, gender inequality on screen has remained largely unchanged and unchecked. Without an educational voice and force for change, this level of imbalance is likely to stay the same or worsen. Only through education, research, and advocacy both from within the studio system and entertainment industry, and with parents and kids, can we effect real change in this heavily gender-biased media landscape.

Gender Inequality in Media

There are many reasons to care about gender issues in the media and entertainment industry—not the least of which is the importance of moving beyond traditional stereotypes and having diverse storytellers share their unique perspectives in film, television, and other forms of print and broadcast media. Women are among the largest consumers of film and television, so they represent a key demographic for this industry and the advertisers that support it.

According to our recent research, women are well represented in media and entertainment companies. But even with corporate America’s increased focus on ensuring gender parity, women in this industry experience a more hostile workplace than men and face a glass ceiling that prevents them from reaching top leadership roles.

Using data from the 2019 Women in the Workplace study, one of the largest and most comprehensive data sets of women in corporate America, McKinsey created a one-year snapshot of how women are progressing in media and entertainment and how their workplace experiences differ from those of men. We supplemented that information with collected data from 15 companies, as well as workplace-experience-survey responses of 1,700 employees —both male and female—from the media and entertainment industry in 2019.

We observed some positive trends. At early tenures, for instance, women in media and entertainment are at equal representation as men, which provides a stable foundation for the future. What’s more, at early tenures, promotion rates for women exceed those for men, and the share of women hired from outside the company is equal to or surpasses the share of men. The women in our research also reported high satisfaction with their career choices, as well as a strong desire to be promoted and otherwise advance in their organizations. HR respondents in this industry tended to say their companies were committed to achieving greater parity: 93 percent of them stated that gender diversity was a priority for their organizations.

Almost half of the women in our research said they believe that women in the industry are judged by different standards than men. More important, they consider these gender-biased appraisals to be one of the biggest challenges to getting equal numbers of women and men in management at their organizations.

The numbers suggest that women are more aware of the biases facing other women than men are, with 34 percent of women reporting that they had heard or seen biased behavior toward women in the past year—a number that is 2.7 times higher than their male counterparts (Exhibit 6). This awareness gap can make it difficult for companies to mobilize and address issues with women’s workplace experiences. If men, who still make up four of every five C-suite executives, don’t perceive that bias toward women is happening, they won’t feel compelled to allocate resources toward fixing the problem.

Our research also suggests that women in this industry experience more microaggressions than women in other industries. Microaggressions are brief, often unintended, actions that can slight or marginalize a coworker—for instance, being interrupted while talking or having others explain things to you that you already know. Microaggressions can undermine women’s confidence, inhibit their sense of belonging, and limit their opportunities for advancement. As compared with women in an all-industry benchmark, women in media and entertainment were more likely to report experiencing microaggressions in nine out of the ten categories we asked about (Exhibit 7). What’s more, women of color reported experiencing microaggressions at higher rates than their white peers.

In the wake of such obstacles, 49 percent of women in the media and entertainment industry reported that their companies provided clear and safe ways to voice grievances and concerns, compared with 57 percent in all industries. The good news is that women are demanding even more: almost a third of the women surveyed in media and entertainment reported becoming more outspoken in the past two years about how women are treated at work.

As the numbers suggest, there are many obstacles for women in media and entertainment. But the two biggest challenges are the lack of women’s representation in senior positions and the culture of biased behavior that negatively affects women’s day-to-day experiences in the workplace. There are tangible ways that companies can tackle both and help to level the playing field in the media and entertainment industry.

Participation and influence of women in the media

Studies have found that although the number of women working in the media has been increasing globally, the top positions (producers, executives, chief editors and publishers) are still very male-dominated (White, 2009). This disparity is particularly evident in Africa, where cultural impediments to women fulfilling the role of journalist remain (e.g. travelling away from home, evening work and covering issues such as politics and sports which are considered to fall within the masculine domain) (Myers, 2009). The Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) reports that throughout the world, female journalists are more likely to be assigned ‘soft’ subjects such as family, lifestyle, fashion and arts. The ‘hard’ news, politics and the economy, is much less likely to be written or covered by women.

The level of participation and influence of women in the media also has implications for media content: female media professionals are more likely to reflect other women’s needs and perspectives than their male colleagues. It is important to acknowledge, however, that not all women working in the media will be gender aware and prone to cover women’s needs and perspectives; and it is not impossible for men to effectively cover gender issues. Recent research from 18 disparate countries shows that male and female journalists’ attitudes do not differ significantly (Hanitzsch & Hanusch, 2012). Nonetheless, the presence of women on the radio, television and in print is more likely to provide positive role models for women and girls, to gain the confidence of women as sources and interviewees, and to attract a female audience.

Media content and portrayal of men and women in the media

Fair gender portrayal in the media should be a professional and ethical aspiration, similar to respect for accuracy, fairness and honesty (White, 2009). Yet, unbalanced gender portrayal is widespread. The Global Media Monitoring Project finds that women are more likely than men to be featured as victims in news stories and to be identified according to family status. Women are also far less likely than men to be featured in the world’s news headlines, and to be relied upon as ‘spokespeople’ or as ‘experts’. Certain categories of women, such as the poor, older women, or those belonging to ethnic minorities, are even less visible.

Stereotypes are also prevalent in every day media. Women are often portrayed solely as homemakers and carers of the family, dependent on men, or as objects of male attention. Stories by female reporters are more likely to challenge stereotypes than those filed by male reporters (Gallagher et al., 2010). As such, there is a link between the participation of women in the media and improvements in the representation of women.

Men are also subjected to stereotyping in the media. They are typically characterized as powerful and dominant. There is little room for alternative visions of masculinity. The media tends to demean men in caring or domestic roles, or those who oppose violence. Such portrayals can influence perceptions in terms of what society may expect from men and women, but also what they may expect from themselves. They promote an unbalanced vision of the roles of women and men in society.

Attention needs to be paid to identifying and addressing these various gender imbalances and gaps in the media. The European Commission (2010) recommends, for example, that there should be a set expectation of gender parity on expert panels on television or radio and the creation of a thematic database of women to be interviewed and used as experts by media professionals. In addition, conscious efforts should be made to portray women and men in non-stereotypical situations.

Participatory community media

Participatory community media initiatives aimed at increasing the involvement of women in the media perceive women as producers and contributors of media content and not solely as ‘consumers’(Pavarala, Malik, and Cheeli, 2006). Such initiatives encourage the involvement of women in technical, decision-making, and agenda-setting activities. They have the potential to develop the capacities of women as sociopolitical actors. They also have the potential to promote a balanced and non-stereotyped portrayal of women in the media and to challenge the status quo. In Fiji, women who took part in a participatory video project presented themselves as active citizens who made significant contributions to their families and communities. These recorded images improved the status of women in the minds of government bureaucrats.

There are limitations to participatory community initiatives, however. If unaccompanied by changes in structural conditions, participation may not be sufficient to foster substantive social change. Baú (2009) explains that the establishment of a women’s radio station (run and managed by women) in Afghanistan faced constraints in that women engaged in self-censorship in order to avoid criticism from local male political and religious leaders.

Changing attitudes and behavior

Communication for Development (C4D)

The approach to Communication for Development (C4D) has evolved over the years. Initially developed after World War II as a tool for diffusion of ideas, communication initiatives primarily involved a one-way transmission of information from the sender to the receiver. This includes largescale media campaigns, social marketing, dissemination of printed materials, and ‘educationentertainment’. Since then, C4D has broadened to incorporate interpersonal communication: faceto- face communication that can either be one-on-one or in small groups. This came alongside the general push for more participatory approaches to development and greater representation of voices from the South. The belief is that while mass media allows for the learning of new ideas, interpersonal networks encourage the shift from knowledge to continued practice.

Communication for development has thus come to be seen as a way to amplify voice, facilitate meaningful participation, and foster social change. The 2006 World Congress on Communication for Development defined C4D as ‘a social process based on dialogue using a broad range of tools and methods. It is also about seeking change at different levels including listening, building trust, sharing knowledge and skills, building policies, debating and learning for sustained and meaningful change’. Such two-way, horizontal approaches to communication include public hearings, debates, deliberations and stakeholder consultations, participatory radio and video, community-based theatre and story-telling, and web forums.

Communication initiatives aimed at changing attitudes and behaviors

Communication initiatives aimed at changing attitudes and behaviors have increasingly been used in the health sector since the 1970s. Such initiatives – including television and radio shows, theatre, informational sessions and pamphlets – can and have affected social norms related to gender roles, since gender norms are linked to all facets of health behavior. Initiatives that seek to affect gender norms and inequities as a goal in itself, however, are a relatively new phenomenon.

Community radio is considered to be an effective tool in promoting women’s empowerment and participation in governance structures. Radio is often the primary source of information for women. It is accessible to local communities, transcends literacy barriers and uses local languages. Afghan Women’s Hour, for example, aims to reach a large cross-section of women and offers a forum to discuss gender, social issues and women’s rights. It was found that female listeners demonstrated a pronounced capacity to aspire, defined as the ‘capacity of groups to envision alternatives and aspire to different futures’ (Appadurai, cited in Bhanot et al., 2009, p. 13). Women developed specific aspirations in areas that had been recently covered by the program segments. Their aspirations, however, were not particularly focused (Bhanot et al., 2009). Challenges with other community radio program initiatives include women’s general under-representation and in some cases, the negative portrayal of women.

Participatory approaches are considered to be an effective tool in encouraging alternate discourses, norms and practices, and in empowering women. The use of sketches and photography in participatory workshops, for example, has encouraged women who have traditionally been reluctant to engage in public forums to express themselves.

In order for the empowerment of women to have a genuine impact, opportunity structures also need to be addressed, such as conservative and male opinion. Afghan Women’s Hour has a large male audience (research by BBC Media Action found that 39% of listeners were men), which provides a way to challenge male views on gender norms. Group educational activities, a common program for men and boys, also have the potential to contribute to changes in attitudes on health issues and gender relations and, in some cases, changes in behavior.

It is also important for communication initiatives to build on tradition and culture, not only because this can resonate better with communities, but because it can help to mute opposition from conservative segments of society. The involvement in projects of key community leaders such as teachers, cultural custodians and government officials is also important for greater impact and sustainable change.

The Role of the Media in Achieving Gender Equality

Media today, from traditional legacy media to online media, still hugely influence our perceptions and ideas about the role of girls and women in society. What we have unfortunately seen until now is that media tend to perpetuate gender inequality. Research shows that from a young age, children are influenced by the gendered stereotypes that media present to them.

Research has found that exposure to stereotypical gender portrayals and clear gender segregation correlates “(a) with preferences for ‘gender appropriate’ media content, toys, games and activities; (b) to traditional perceptions of gender roles, occupations and personality traits; as well as (c) to attitudes towards 2 expectations and aspirations for future trajectories of life” . The data we have show that women only make up 24% of the persons heard, read about or seen in newspaper, television and radio news. Even worse: 46% of news stories reinforce gender stereotypes while only 4% of stories clearly challenge gender stereotypes.

One in five experts interviewed by media are women. Women are frequently portrayed in stereotypical and hyper-sexualized roles in advertising and the film industry, which has long-term social consequences. And 73% of the management jobs are occupied by men compared to 27% occupied by women.

The media can play a transformative role in achieving gender equality in societies by creating gender-sensitive and gender-transformative content and breaking gender stereotypes, challenging traditional social and cultural norms and attitudes regarding gender perceptions both in content and in the media houses, and showing women in leadership roles and as experts on a diversity of topics on a daily basis, not as an exception.

In many countries around the world women’s opinions are dismissed and they are not taught to ask questions and be part of public debate. Without information women don’t know about and can’t exert their rights to education, to property, pensions, etc. and they cannot challenge existing norms and stereotypes. This makes it impossible to achieve inclusive societies. Access to information empowers women to claim their rights and make better decisions.

Case Study:

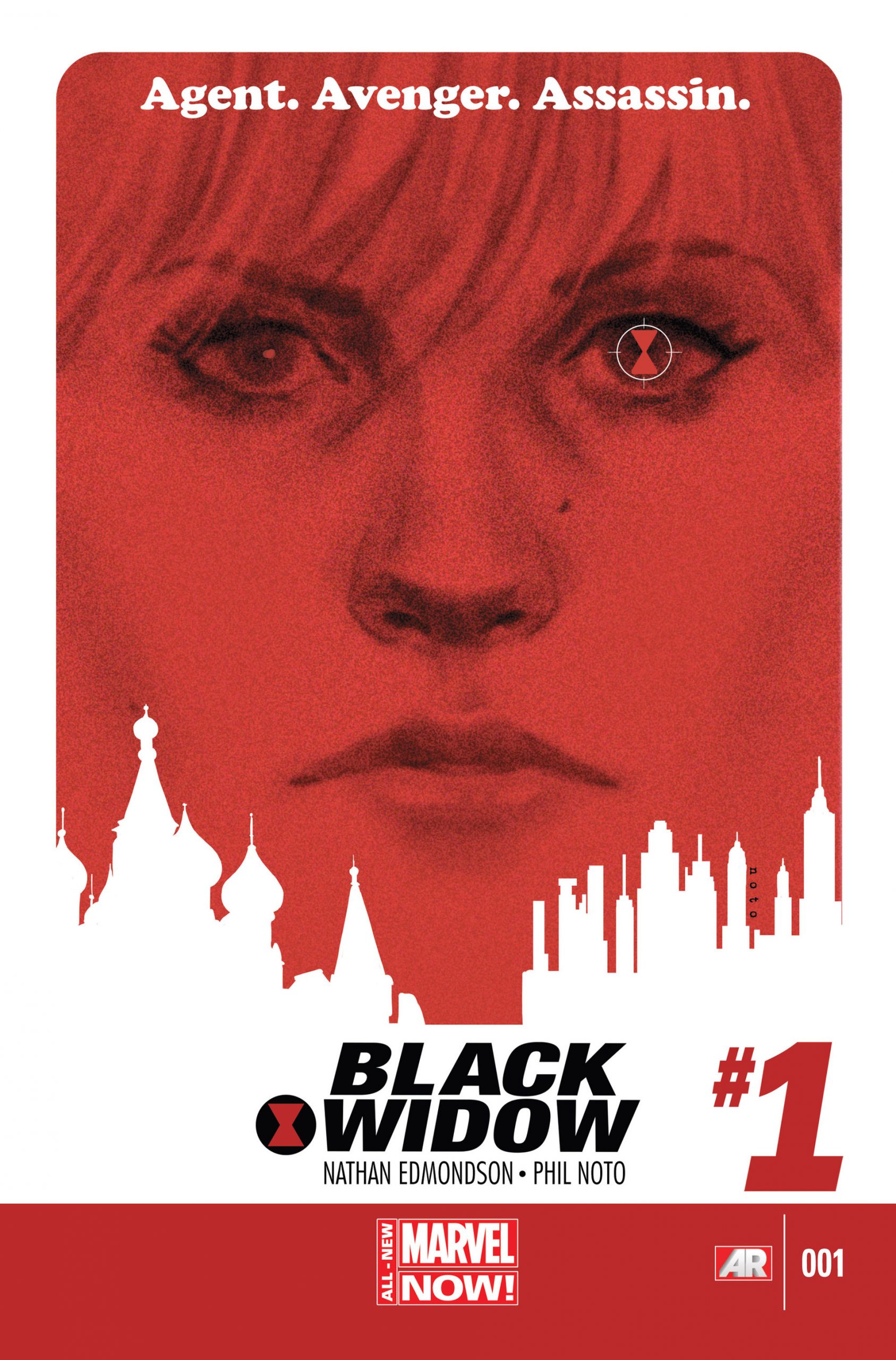

Black Widow

Synopsis: The Politics of Gender in Black Widow (link)

Black Widow in Comics

Black Widow on Film