21

Ballet in the Modern Period

Modern dance encourages dancers to use their emotions and moods to design their own steps and routines. It is not unusual for dancers to invent new steps for their routines, instead of following a structured code of technique, as in ballet. Another characteristic of modern dance, in opposition to ballet, is the deliberate use of gravity. Whereas classical ballet dancers strive to be light and airy on their feet, modern dancers often use their body weight to enhance movement. This type of dancer rejects the classical ballet stance of an upright, erect body, often opting instead for deliberate falls to the floor.

Isadora Duncan (1877 – 1927)

Considered by many to be the creator of the modern dance movement, Isadora Duncan believed in a free form of dance that established emotional expression through less restrictive movement. Duncan was inspired by the historical and unconventional drama of art including Greek arts, folk dances, social dances, nature, and natural forces as well as American athleticism such as skipping, running, jumping, leaping and tossing. Exemplifying her belief in unrestricted expression, Duncan often performed barefoot and in more freeing costumes than preceding dance forms. Duncan performed across the world and established many schools of dance during her career, all of which further developed the modern dance movement as a true form of dance.

R uth St. Denis (1879 – 1968)

uth St. Denis (1879 – 1968)

Ruth St. Denis introduced seudo exoticism into the repertoire of the modern dance movement. Inspired by foreign cultures, Denis transformed aspects of culture into an entertaining art form that lacked authenticity but delivered originality in exotic mysticism and spirituality. With a strong belief that dance was a spiritual expression, her work appealed to the period’s fascination with the orient. The co-founder of the American Denishawn School of Dance, one of her most famous pupils was Martha Graham.

Martha Graham (1894 – 1991)

Martha Graham (1894 – 1991)

Martha Graham created a technique that combined functions of modern dance and ballet to codify and structure modern dance movements. Graham was a student under the Denishawn school where she developed her passion of the modern dance movement. Focusing on more systematic concepts of the movement, such as contraction and release, Graham introduced structure to a movement that first found its identity in rebelling against rigid dance forms.

Modern dance has become a huge genre in the dance world today and is typically listed as a class offered on the schedules of most dance studios. Some dancers feel that modern dance gives them a chance to enjoy ballet dancing without the strict focus on their technique and turnout.

The Rite of Spring

Russian choreographers, composers, and dancers who toured Europe created Modern ballet at the turn of the 20th century, which was vastly different than its predecessors. Movements were choppy and sharp and the music was staccato. The stories they conveyed were also less charming than before. It was initially hated by audiences and reviled by critics.

The idea for Le Sacre du Printemps [The Rite of Spring] came from Russian painter and archaeologist Nikolai Roerich, who had a lifelong interest in pagan and peasant spirituality and the roots of Russian culture. Igor Stravinsky composed a score that was dissonant, syncopated, and haunting. Sergei Diaghilev’s choreography was jerky, awkward, and angular, with dancers gathered in clumps, bent, quivering, and huddled, hunched and shuffling. Needless to say, this was a radical detour from former traditions of ballet, which was not appreciated. Its first performance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, on May 29, 1913, resulted in the audience rioting, the theater erupting in chaos and mayhem.

East Goes West:

The Making of The Rite of Spring

Then came Le Sacre du Printemps (1913). The ballet originated with Sergei Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, and the Russian artist Nikolai Roerich. Roerich was a painter and archaeologist with a lifelong interest in pagan and peasant spirituality and in the Scythian-savage, rebellious, Asiatic roots of Russian culture. He was deeply involved at Talashkino, and indeed, he and Stravinsky created the ballet’s scenario there amid the Princess Tenisheva’s vast collection of peasant arts and crafts. Drawing on the work of folklorists and musicologists, they conceived the new ballet as a ritual reenactment of an imagined pagan sacrifice of a young maiden to the god of fertility and the sun: a rite of spring. Roerich patterned the decor on Russian peasant crafts and clothing, and Stravinsky studied folk themes (“The picture of the old woman in a squirrel fur sticks in my mind. She is constantly .before my eyes as I compose,” he wrote of one section). But this was not the lush orientalism of The Firebird: Roerich’s sets depicted an eerily barren and rocky landscape strewn at points with antler heads. Stravinsky’s music, with its loud, static, and dissonant chords, its driving syncopation (the score called for an expanded orchestra and large percussion section) and haunting melodies reaching into extreme registers, was similarly brutal and disorienting.

Nijinsky admired Stravinsky and Roerich enormously and wrote to Bronislava Nijinska, who originally worked with Nijinsky on the role of the sacrificial Chosen One, of Roerich’s painting The Call of the Sun: “Do you remember it Bronia? … the violet and purple colors of the vast barren landscape in the predawn darkness, as a ray of the rising sun shines on a solitary group gathered on top of a hill to greet the arrival of spring. Roerich has talked to me at length about his paintings in this series that he describes as the awakening of the spirit of primeval man. In Sacre du Printemps I want to emulate this spirit of the prehistoric Slavs.” And to Stravinsky, who had conferred at length with the young choreographer about the music, he wrote that he hoped Sacre du Printemps would “open new horizons” and be “all different, unexpected, and beautiful.”

And so it was. The ballet was performed only eight times ever and the choreography was then forgotten, but pictures and notes show just how disarmingly unballetic it was: hunched figures shuffled, stomped, and turned their feet into awkward, pigeon-toed poses with arms curled and heads askew. The movements were jerky and angular, with dancers gathered in clumps, bent, quivering and huddled, orcir cling furiously in traditional round dances and then compulsively thrust from the ring or thrown into wild jumping motions. Nijinsky devised uncomfortably uncoordinated movements in which”the arms moved in one rhythm and the legs in another, and one dancer recalled leaps that crashed deliberately onto flat feet, jarring “every organ in us.”

Stravinsky’s score posed daunting challenges. Nijinsky’s only other ballets had both been created to music by Debussy. But Sacre du Printemps had none of the oceanic calm or expansiveness of Faune, and Nijinsky struggled to make sense of Stravinsky’s strange new sounds and complicated rhythmic and tonal structure. Even the rehearsal pianist couldn’t get it right: on one occasion Stravinsky impatiently pushed him aside and took over,play ing twice as fast, shouting, singing, stamping his feet, and banging out rhythms with his fists to convey the sheer percussive energy and volume of the music (the dancers would not hear the fully orchestrated music until the final stage rehearsals). In an effort to help, Diaghilev hired the young Polish dancer Marie Rambert (born Cyria Rambam), a specialist in the Dalcroze method of Eurythmic dancing. to assist Nijinsky and rehearse the performers. She and Nijinsky spoke Polish together, and she was sympathetic to his radical approach to movement. But nothing seemed to work: the dancers found the score disconcertingly opaque and almost impossible to count, and they hated Nijinsky’s intricate steps and stylized movements. In the end, however, their resistance may have served the ballet well: forced submission to the logic of the music and movements was exactly the point.

Le Sacre du Printemps was not a ballet in any traditional sense of the word. There was no easy narrative development or room for individual self-expression, and no conventional theatrical landmarks by which to gauge the action. The ballet worked instead by repetition, accumulation, and an almost cinematographic montage: static scenes and im ages juxtaposed and driven forward by a ritual and musical rather than strictly narrative logic. There were stomping tribal dances and a stylized movements, the ceremonial abduction of the chosen maiden, and a solemn procession led by a white-bearded high priest that culminated in the girl’s agonizing dance of death. At the end, when the virgin col lapsed dead to the floor and six men raised her limp body high above their heads, there was no cathartic outpouring of despair, sadness, or anger, only a chilling resignation.

It is difficult to convey today just how radical Sacre du Printemps was at the time. The distance separating Nijinsky from Petipa and Fokine was im mense; even Faune was tame by comparison. For if Faune represented a studied retreat into narcissism, Sacre signaled the death of the individual. It was a bleak and intense celebration of the collective will. Everything was laid bare: beauty and polished technique were nowhere to be seen, and Nijinsky’s choreography made the dancers halt midstream, pull back, and redirect or change course, breaking their movement and momentum as if to release pent-up energies. Control and skill, order, reason, and ceremony, however, were not set aside. Nijinsky’s ballet was never wild or discursive: it was a coldly rational depiction of a primitive and irrationally charged world.

It was also a defining moment in the history of ballet. Even at its most rebellious moments in the past, ballet had always had anunder lying nobility: it cleaved to anatomical clarity and high ideals. Not so with Sacre. Nijinsky modernized ballet by making it ugly and opaque: “I am accused,” he boasted, “of a crime against grace.” Stravinsky admired him for it: the composer wrote to a friend that the choreography was “as I wanted it,” although he added, “One must wait a long time before the public becomes accustomed to our language.” This was exactly the point: Sacre was both difficult and genuinely new. Nijinsky had thrown the full weight of his talent into breaking with the past, and the feverishness with which he (like Stravinsky) worked was an indication of his fierce ambition to invent a whole new dance language. This is what drove him, and it made Sacre the first truly modern ballet.

What the French thought of the Ballets Russes was another story. And it was the French that mattered, for although the Ballets Russes performed across continental Europe and in Britain (and eventually the Americas), no city was more important to its success than Paris. It was Paris that embraced the company and elevated ballet -Russian ballet – to the apex of modernism in art. The way had been well prepared. The rapprochement between Russia and France culminating in the Franco-Russian alliance of 1894 and the Triple Entente (with Britain) in 1907 had sparked renewed interest in Russian culture and art. Parisians bought up billfolds picturing the river Nevap, portraits of the tsar and tsarina, and matchboxes stamped with Russian scenes; Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky were widely read and discussed. In 1900, Paris had hosted an exhibition of Russian arts and crafts, including a model Russian village designed by Korovin and built, Talashkin style, with Russian peasant hands. And as we have seen, Diaghilev’s own art exhibition and performances of Russian opera followed. But it was not only the Russians who gave the East its renewed sheen. The glamorously exotic dancer and courtesan Mata Hari (who was Dutch) made her Parisian debut in 1905, and the American dancer Ruth Denis arrived the following year with her pseudo-Indian and oriental choreographies. In a different but related key, Isadora Duncan arrived in the capital in 1900, and her free-form dances became the height of Parisian chic. The stage had been set for the Ballets Russes.

Who paid for them to come? The Russian state initially helped quite a lot: costumes, sets, dances, and music were courtesy of the tsar’s Imperial Theaters. But this arrangement did not last and Diaghilev, who had few resources of his own and diminishing support from the Russian court, was increasingly thrown into the market place. Ballet may have been less costly than opera, but it was still a daunting undertaking, and without the support of a wealthy state the odds of sustaining such a costly enterprise were slim. Thus in spite of the Ballets Russes’ critical success, Diaghilev’s early ballet seasons often left the impresario broke: at one point the sets and costumes even had to be hawked to a competitor to settle the debt. And so Diaghilev worked hard, very hard, to win the support of the local French (and European) elite: he charmed, cajoled, and connived, twisted arms, and played one party off another, telegrams flying, to hold the far-flung finances of his enterprise together.

Diaghilev courted prominent diplomats, government officials, and bankers, and worked closely with the maverick Parisian impresario Gabriel Astruc, who built the Theatre des Champs-Elysees (where Faune had its premiere) and who counted Rothschilds, Vanderbilts, and Morgans among his patrons. But above all, he fit in with the French aristocracy and was taken up by prominent salonnieres: the elegant Comtesse Greffuhle (a model for Proust’s Duchesse de Guermantes) and Princesse Edmond de Polignac (an American sewing-machine heiress who had married into the French aristocracy) were loyal friends and supporters; so was Misia Edwards, a Pole born in Russia, raised in Paris, and married first to a newspaper magnate and later to the Spanish artist Jose Maria Sert. Leaders in taste and fashion, these women, and others like them, gave the Ballets Russes a coveted high-society cachet. De signers were quick to follow their lead: the couturier Paul Poiret took up the Ballets Russes look in exotic and flowing fashions that challenged the old corseted styles, and the young Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel became a close friend to Diaghilev and would herself also design ballet costumes.

What really established the Ballets Russes, however, was not social connections or commercial interests but the artistic climate in the French capital. Over the previous thirty years, Parisian confidence had been shaken by a series of unnerving events, beginning with the city’s defeat at the hands of the Prussians in 1870-71 and the subsequent violent revolutionary upheaval of the Commune. War scares, anarchist bombings, and the bitter feuds unleashed by the Dreyfus Affair further intensified anxieties. A dwindling birthrate, moreover, along with periodic economic depressions, were seen by many as signs of at rophy and decline. In culture and art, the confident positivism of the mid-nineteenth century gave way to a fascination with decadence and the irrational.

Everywhere, appearances no longer seemed a reliable guide to reality. Even science said so: hitherto commonly held assumptions about truth and the immutable laws of nature were undermined by the discovery of X-rays and radioactivity, which proved the existence of hid den and invisible forces hitherto relegated to the imagination. Einstein’s early revelations of possible new dimensions in space and time and a distinct atomic world governed by its own physical laws had a similarly jarring and expansive effect and seemed to consign the old Newtonian certainties to the past. Equally unsettlirig were Freud’s exacting descriptions of the secret and irrational workings of the sub conscious mind: dreams, sex, and dark psychological realities under mined traditional views of human behavior and .motivation.

French artists registered these broader cultural upheavals, and created their own. In literature, Marcel Proust (a Ballets Russes devotee) found a way to document what he once called the “shifting and con fused gusts of memory.” Music found a correlative in Debussy’s Impressionistic sound, with its new and constantly shifting tonalities, and in subsequent innovations by composers such as Ravel, Poulenc, and Satie-all of whom would work with Diaghilev. The musical links with Russia were long-standing: Debussy had visited Russia in 1881 and admired Glinka and Mussorgsky, and he and Ravel both fol lowed and drew from Rimsky-Korsakov. The emerging art ©f cinema drew on similar undercurrents and seemed to exemplify the era: here was a machine-age “magic” that promised to show dreams and illuminate heretofore secret and unseen dimensions of human experience. The parallel with the Ballets Russes was direct and irresistible, leading one observer to dub the company the “cinematograph of the rich.”

But it was developments in painting and art that mattered most for dance. The years preceding the arrival of the Ballets Russes saw a growing interest in “primitive” African art and masks, which seemed to embody elemental truths long abandoned by the “civilized” West. In 1907 Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d‘Avignon launched Cubism. The painting’s vulgar subject (his models were prostitutes), fractured and multiple perspectives, and raw energy shocked just about every one. (Braque said it made him feel sick, as if he had swallowed petrol.) In a different key, the following year Henri Matisse showed Harmony in Red: flat and decorative, it “sang, no screamed color and radiated light” and seemed to more than one observer “new and ruthless in its unbridled freedom.” Two years later, the artist completed Dance and Music, huge, Dionysian works painted on eight-by-twelve-foot panels. He was not alone in his fascination with dancers: Picasso and Andre Derain (among others) would also attempt to express the rhythm and physicality of dancers in motion. Matisse’s early dancers and musicians, however, created an uproar in Paris: at the opening people jeered and critics called the paintings bestial and grotesque, a “cave-man” art.

The Russians knew otherwise. In a sign of the converging of taste in French and Russian art, all three Matisse paintings were purchased by the Moscow-based merchant collector Sergei Shchukin; who al ready had more than a dozen Gauguins hanging in his dining room and would become an important patron of Picasso. Shchukin’s fortune came from importing oriental textiles and his eye was accustomed to the patterns and bright colors of the East. When Matisse visited Moscow, he was astonished by Russian folk art and religious icons. “Russians do not realize what treasures they possess,” he said, “every where the same vividness and strength of feeling … such wealth and purity of colour, such spontaneity of expression I have never seen anywhere before.” He told a group of Russian artists (including Natalya Goncharova, who was soon to join the Ballets Russes in Paris), “It’s not you who should be coming to learn from us, we should be learning from you.”

And so the French did. The Ballets Russes seemed to fuse all of the underlying currents of modernism into a single electrifying charge. Here was an art that was vibrant and colorful (Bakst talked about “reds that assassinate”), dreamy and interior, but also primitive and erotic, “ruthless in its unbridled freedom.” It was visual, musical, and above all physical: an immediate and visceral assault on all of the senses which painting and literature could only approximate. If movement, broken and staccato rhythms, and the dynamic juxtaposition of elements were guiding principles of modernism, then the Ballets Russes had them all: live. Pavlova’s piercing fragility, Nijinsky’s ani mal virility (“undulating and brilliant as a reptile”), and Karsavina’s elevated but sensual allure seemed to embody the energy and vitality so lacking in an “old, tired” Europe. Critics rushed to proclaim “this voluptuous performance, at once barbarous and refined, sensual and delicate,” and over and again they found themselves astonished and delighted by the urgency, attack, and full-blooded passion of the Russian dancers. Compared to them, one critic lamented, the French seemed “too civilized … too retreating: we have lost the custom of expressing ourselves with the whole body …. We are all in our heads.” The Ballets Russes had not only revived the art of dance (which the French had so regrettably left to languish); they promised to rejuvenate civilization itself.

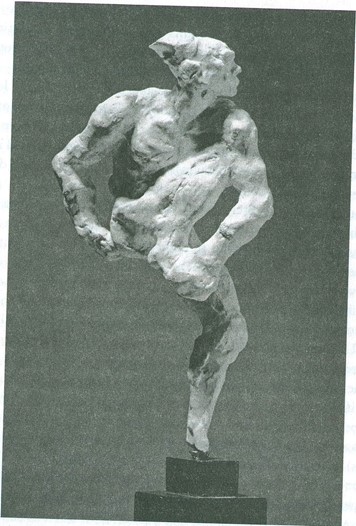

This was the reception accorded Fokine and the company’s early. “Russian” ballets. After 1912, however, things changed dramatically. First came the shock of Faune. According to Fokine (who hated the ballet), the preview performance before an audience of critics, patrons, and other notables was so incomprehensible that the dance had to be repeated a second time. The press was outraged: a front-page article in Le Figaro written (unusually) by the paper’s editor squealed, “False Step,” and found the “lecherous faun” to be “filthy and bestial.” The police were called in for the second performance-which sold out. Nijinsky, however, had important defenders: Auguste Rodin wrote a letter (which Diaghilev immediately printed and circulated) praising the dancer and his ballet. That same year, the sculptor created his own bronze cast of Nijinsky. It showed the dancer crouched and bent on one leg with the other knee crushed to his chest, torso twisted with rippling muscles, a mask-like face, flared nostrils, and high, sculpted cheekbones: a perfect statement of Nijinsky’s own attempts to reinvigorate an etiolated classicism.

The uproar over Faune, however, was nothing compared to the brawling commotion that greeted the opening performance of Le Sacre du Printemps on May 29, 1913. Although firsthand accounts vary Wildly and the events of that evening were almost immediately obscured by the fog of the ballet’s own myth, we know that Diaghilev – no stranger to the commercial value of controversy – deliberately stocked the house with the adherents of rival and feuding artistic factions who could be counted on to create a ruckus. Moreover, the impresario had deftly fueled expectations: invitation-only stage rehearsals heightened public interest, and advance publicity loudly proclaimed the ballet a new “real” and “true” art. Capitalizing on Nijinsky’s already controversial reputation, ticket prices had beendou bled. But whatever prior antagonisms and anticipations existed in the theater that night, it was Stravinsky’s music and Nijinsky’s dances that set the audience to riot.

Shouting, yelling, pitching chairs, and police: the outcry was loud and physical. Those who were there that first night (and even some, such as Gertrude Stein, who thought they had been there but were not) never forgot it. Indeed, the show in the house was at least as impressive and unnerving as the show onstage: the theater, it was said, was “shaken like an earthquake” and seemed to “shudder.” When the dancers held their cheeks in a strange pose, people cried out, “Un docteur! Un dentiste! Deux dentistes!” and one man was reportedly so en grossed that he compulsively beat the rhythms of Stravinsky’s music on the head of the critic standing in front of him. In their intense identification with the events onstage, the audience- hecklers and supporters alike – seemed to be enacting their own rite. They canonized and mythologized the ballet on the spot, elevating it (and themselves) to icons of modern art.

But why? The best answer we have comes from the critic and editor Jacques Riviere. Riviere was an admirer of Gauguin, publisher of Proust and Andre Gide, and deeply interested .in instinctive andsub conscious forms. He was drawn to Nijinsky’s choreography for its raw, unadorned aesthetic; it was, he said, a ballet entirely without “sauce.” Cold and clinical, it was a “stupid” and “biological” dance of “colonies” and “cells in mitosis.” “It is a stone full of holes, from which unknown creatures crawl intent on work that is indecipherable and long sinceir relevant.” Its dances left him inert and filled with anguish: “Ah! How far I was from humanity!” Yet even if the ballet described a “stupid” and shockingly indifferent social organism, it was itself supremely or dered and rigorously performed. Sacre, he suggested, proclaimed a new classicism: rule-driven and disciplined, it trained its eye not on the reason and noble ideals of the past but on their immolation.

What Riviere had pinpointed and many others felt was not just the nihilism of Nijinsky’s vision, nor did it have much to do with the ur Russian overtones that had been so important to Nijinsky, Roerich, and Stravinsky’s ow thinking about the work. For audiences in Paris in 1913, Le Sacre du Printemps was first and foremost a betrayal. It abandoned once and for all the vital, intensely human, and sensual dance that audiences had come to expect from the Ballets Russes (Nijinsky, their favorite star, did not even appear – instead he stood in the wings shouting counts at the dancers). The Russians, it seemed, would not rejuvenate a languishing European civilization at all: instead they would describe and promote its willful self-destruction.

Critics called it the massacre du printemps, seeing in it a threatening depiction of a diminished humanity. And indeed, as events pushed the Continent closer to war, Sacre was increasingly understood as an omi nous prelude. Not long after the assassination of the Austrian arch duke, a French critic declared Sacre du Printemps a “Dionysian orgy dreamed of by Nietzsche and called forth by his prophetic wish to be the beacon of a world hurtling toward death.” For Parisians, Sacre was not a celebration of the “spirit of the prehistoric Slavs”: it was incriminatory evidence of the decline of Western thought and civilization.

This reading of the ballet stuck. More than that, it set down deep roots that then became entangled with Nijinsky’s own life story and eventual descent into insanity. In the years after Sacre, the dancer’s life unraveled. He impulsively married a Hungarian woman whom he barely knew: in a jealous rage Diaghilev cut him off. Banned from Russia (he had failed to apply for deferral of his military service), Nijinsky tried to make it on his own but was woefully incapable of man aging his affairs. A season at a music hall in London all but undid him, and he recoiled at the prospect of prostituting himself (as he saw it) to a public hungry for exotic Russian dances. During the war, he was interned in his wife’s native Hungary, trapped and dependent on a hostile mother-in-law and removed from the sources of his art. A brief tour to America (engineered by Diaghilev, who did not forgive the dancer but needed his fame) did not help: ill health, artistic frustration, bitter disputes with Diaghilev, and a growing obsession with Tolstoyan religious dogmas – Nijinsky liked to dress in peasant tunics and dreamed of returning to Russia to work the land – eventually resulted in physical and financial collapse.

In 1919, in the first stages of the madness that would overtake him, he performed a final solo dance in St. Moritz. It was the last dance he would ever perform: he was subsequently institutionalized and died in 1950. Dressed in simple loose-fitting pants and shirt with sandals, he placed a chair in the center of the room and sat stoically staring at the fashionably dressed audience while the pianist played uncomfortably on. Finally, in silence, he took two bolsters of fabric and rolled out a large black and white cross. He stood at its head with arms open, Christ-like, and spoke of the horrors of the war: “Now I will dance the war … the war which you did not prevent and are also responsible for.” Nijinsky’s final Rite of Spring.

When the war broke out in 1914, the Ballets Russes disbanded. Some of the dancers, including Karsavina and Fokine (who had returned briefly to the company after Nijinsky’s departure), made the arduous journey home. Fokine staged several works in St. Petersburg but soon left for engagements in Scandinavia – he was there when the Russian Revolution broke out – and eventually made his way to America, where he settled in 1919. Karsavina resumed her career at the Imperial Theaters (she too would eventually settle in the West). Although conditions were difficult, the war had the paradoxical effect of restoring the Imperial ballet to its former grandeur. As Maurice Paleologue, then French ambassador to Russia, noted in his memoirs, the heroism and “dash” of the tsar’s military found their civilian counterpart in the full-dress formality of the Imperial ballet. Indeed, as war losses mounted and the country’s situation grew increasingly dire, classical ballet served as a wistful reminder of past grandeur. Paleologue’s own tastes were more modern (he adored Karsavina), and he was amazed at the latent enthusiasm in high quarters for the “archaic” dancing of Kschessinska, with its “mechanical precision” and “giddy agility.” An old aide-de-camp explained: “Our enthusiasm may seem somewhat exaggerated to you, Ambassador; but Tchechinska¥a’s {Kschessinska’s} art represents to us … a very close picture of what Russian society was, and ought to be. Order, punctiliousness, symmetry, work well done everywhere … Whereas these horrible modern ballets-Russian ballets, as you call them in Paris-a dissolute and poisoned art-why, they’re revolution, anarchy!”

Russian Modernism and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes:

When The Rite of Spring incited a riot in a Paris theater

It began with a bassoon and ended in a brawl.

One hundred years ago today, Russian composer Igor Stravinsky debuted The Rite of Spring before a packed theater in Paris, with a ballet performance that would go down as one of the most important — and violent — in modern history.

Today, The Rite is widely regarded as a seminal work of modernism — a frenetic, jagged orchestral ballet that boldly rejected the ordered harmonies and comfort of traditional composition. The piece would go on to leave an indelible mark on jazz, minimalism, and other contemporary movements, but to many who saw it on that balmy evening a century ago, it was nothing short of scandalous.

Details surrounding the events of May 29th, 1913 remain hazy. Official records are scarce, and most of what is known is based on eyewitness accounts or newspaper reports. To this day, experts debate over what exactly sparked the incident — was it music or dance? publicity stunt or social warfare? — though most agree on at least one thing: Stravinsky’s grand debut ended in mayhem and chaos.

The tumult began not long after the ballet’s opening notes — a meandering and eerily high-pitched bassoon solo that elicited laughter and derision from many in the audience. The jeers became louder as the orchestra progressed into more cacophonous territory, with its pounding percussion and jarring rhythms escalating in tandem with the tensions inside the recently opened Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

Things reached a near-fever pitch by the time the dancers took the stage, under the direction of famed choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky of the Ballets Russes. Dressed in whimsical costumes, the dancers performed bizarre and violent moves, eschewing grace and fluidity for convulsive jerks that mirrored the work’s strange narrative of pagan sacrifice. Onstage in Paris, the crowd’s catcalls became so loud that the ballerinas could no longer hear the orchestra, forcing Nijinsky to shout out commands from backstage.

A scuffle eventually broke out between two factions in the audience, and the orchestra soon found itself under siege, as angry Parisians hurled vegetables and other objects toward the stage. It’s not clear whether the police were ever dispatched to the theater, though 40 people were reportedly ejected. Remarkably, the performance continued to completion, though the fallout was swift and brutal.

Henri Quittard, a music critic at French daily Le Figaro, described the debut as an exercise in “puerile barbarity,” suggesting that Stravinsky had been corrupted by Nijinsky and Sergei Diaghilev — the impresario who founded the Ballets Russes and who had already stirred controversy for his company’s erotic interpretation of Claude Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune.

It remains unclear whether theatergoers that night were more disturbed by Stravinsky or Nijinsky, whose primitivist choreography may have been as viscerally shocking as the composer’s unusual dissonance. Others have speculated that the event may have been orchestrated either as an elaborate publicity stunt on the part of Diaghilev, or as an operation planned by disgruntled traditionalists.

“The stories of the ‘near riot’ may have become exaggerated over time,” Daniel Weymouth, associate professor of composition and theory at Stony Brook University, said in an email to The Verge. “There is evidence that the ruckus started between two factions at the Paris Opera — those who liked things tame and ‘pretty’ and those who were eager for something new — who were already primed for a confrontation.”

By the early 1900s, Paris had become something of a fulcrum between tradition and modernity. The shift accelerated with the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower in 1889 — a hulking metallic bullseye that drew scathing critiques, controversy, and millions of tourists. Around the same time, telephones, elevators, and other innovations were just making their ways into buildings, bringing with them a looming sense of change and technological upheaval.

These shifts crystallized in the arts, as well. Pablo Picasso began exploring new modes of Cubist representation, while Gertrude Stein and other Paris-based writers were testing the limits of language, searching for meaning that transcended lyricism and traditional narrative.

In some ways, this tension between old and new aesthetics reached a boiling point with The Rite‘s debut, marking an explosive cultural shift unlike any in recent memory. Nowadays, it’s difficult to imagine any single piece of art sparking the kind of turmoil that Stravinsky’s did a century ago.

Even by contemporary standards, Stravinsky’s harsh dissonance, complex rhythms, and repetitive melodies still seem avant-garde. There’s a palpable sense of disconnect, as well — an unsettling step into a world governed not by human emotions or reason, but something else altogether. (Stravinsky himself once said that “there are simply no regions for soul-searching in The Rite of Spring.”)

“Even the youngest composers coming to the fore today listen to The Rite and think, ‘My God,'” Alex Ross, music critic at The New Yorker, told NPR this month. “It still sounds new to them.”

The incident catapulted Stravinsky to international stardom as well, despite the negative early reviews that came out of Paris.

“One result of the so-called ‘riot’ was that Stravinsky effectively became the world’s leading contemporary composer,” says Eric Charnofsky, a composer and lecturer at Case Western Reserve University, describing him as “the one whose subsequent musical ventures defined ‘modernism’ in the minds of audiences and critics.”

This evening, the Mariinsky Ballet will celebrate The Rite‘s 100th anniversary with a performance at the same theater where it debuted to boos and violence. The ballet will be broadcast live on French national television and live-streamed on a giant outdoor display in front of the Hôtel de Ville in central Paris.

When audiences gather tonight, they won’t be doing so in protest and they likely won’t come armed with vegetables. Instead, they’ll convene to celebrate what Weymouth describes as “one of the great aesthetic monuments of Western art — completely assured, startlingly original, brutal, tender, and altogether wonderful.”