Time-Management Strategies for Success

Following are some strategies you can begin using immediately to make the most of your time. As you review these strategies, reflect on how you’ve managed your time in the past, what your strengths and weaknesses are, and who you want to be as a student.

As we learned in the last chapter, setting SMART goals is one step towards your success. Planning the time to achieve those SMART goals is the next step. How you spend your time will determine whether you achieve your goals. Before figuring out how to best manage your time, it’s a good idea to start by trying to determine how you spend your time during a typical week.

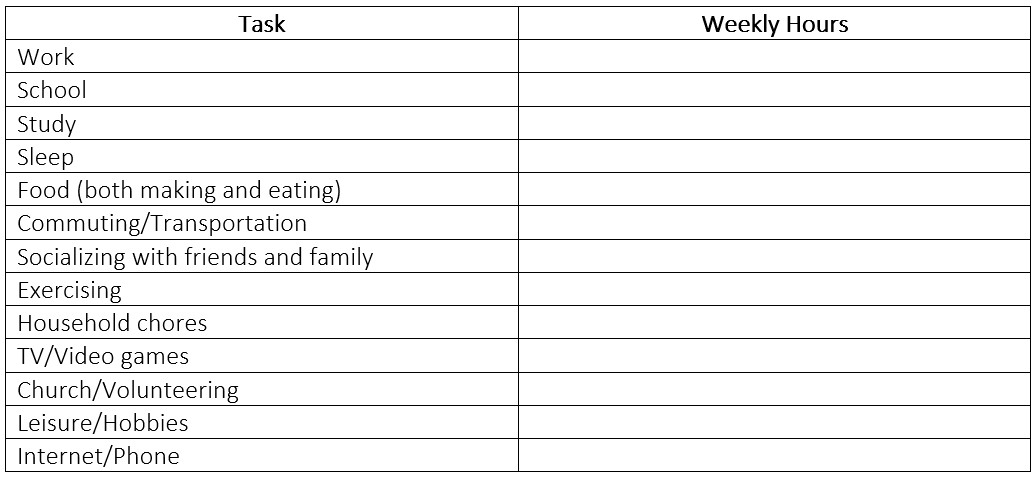

| Optional Activity #1: Where does the time go?

Make a chart similar to the one below. Feel free to change the tasks to fit how you spend your time. Estimate how you spend your time in a typical week. Remember that you have 7 x 24 = 168 hours in a week and try to account for them all.

|

*A tip for determining how much time you spend on your phone or other device is to see if it tracks your daily usage. This number might be larger than you expect! If your daily average is five hours for one week, you spent 35 hours that week on your phone. That’s almost a full-time job! This is an important and often underestimated category of time usage.

Be strategic:

- Assess your most productive time of day. Some people have more energy and focus in the morning, and some prefer working in the evening. Pay attention to your energy levels and ability to focus at different times and then plan your studying time around these factors. You may even prefer to do different tasks at different times of day. For example, you may focus on reading and and studying notes in the morning but want to save creative projects for the evening. If possible, rearrange your other commitments to save your optimal productivity time for studying.

- Break a goal down into subgoals. Whether it’s writing a paper for class, studying for a final exam, or reading a long assignment or full book, you may feel daunted at the beginning of a large project. It’s easier to get going if you break it up into stages that you schedule at separate times—and then begin with the first section that requires only an hour or two. For example, for each assignment or project, create a list of tasks that breaks down the assignment into smaller components. A huge part of time-management is task management.

- Prioritize the most important assignments. When two or more things require your attention, do the more crucial one first. The more crucial one may be the assignment that carries more weight towards your grade or an assignment in a class in which you have a borderline grade. If something unavoidable happens and you can’t complete everything, you will have done the tasks that will have the bigger impact on your grades.

- Find a doable, even fun task to start with. If you have trouble getting started, do an easier task first. Like large assignments, complex or difficult ones can be daunting. If you can’t get started, switch to an easier task you can accomplish quickly. That will give you momentum, and often you feel more confident tackling the difficult task after being successful in the first one. (Although this is the opposite of the eat the frog strategy, it works for some people.)

- Plan breaks. We all need breaks to help us concentrate without becoming fatigued and burned out. As a general rule, a short break every hour or so is effective in helping recharge your study energy. Your brain will continue to process the material you’ve been studying in the background. Get up and move around to get your blood flowing, clear your thoughts, and work off stress.

- Try the Pomodoro Time-Management Technique. This technique uses a timer to set intervals for work, followed by a short breaks. For example, you might set a timer for a 30/10 split—30 minutes of work and then a 10-minute break. Repeat for as long as you intend to study. Experiment to determine a good work/break split for you and your work habits. With practice, you’ll be able to extend the length of the study periods. This technique is particularly helpful when you’re having trouble getting started. For example, if you have a task you are anxious about, try working for 10 minutes and then taking a 10-minute break. Repeat. After an hour, you will have gotten 30 solid minutes of working on your task and 30 minutes doing something you wanted to do. Often, you may find that once you get started, you can work for longer than 10 minutes. Getting started is often the hardest part. You can use your own timer, or you can search for “pomodoro timer” online or in the app store.

- Find pockets of time. You may plan to read a chapter tonight, but if you carry your book with you, you might find time during the day. What if a class is canceled or you have to wait for an appointment? You can start reading early or flip through the chapter to get a sense of what you’ll be reading later. Either way, you’ll save time later. You may be surprised how much you can get done during down times throughout the day.

- Keep your momentum. Avoid distractions, such as multitasking, that will only slow you down. Check your phone, for example, only at scheduled break times. Instead of interrupting your work, make a list of the unrelated things that come to your mind while you are studying. You’ll save time and stay focused.

- Reward yourself. It’s not easy to sit still for hours of studying. When you successfully complete a task, you should feel good and deserve a small reward. A healthy snack, a timed video game session, or a text to a friend can help you feel even better about your successful use of your time.

- Have a life. Never schedule your day or week so full of work and study that you have no time at all for yourself, your family and friends, and your life. Also, take your social life into consideration when making your plan for the week. Don’t schedule a study session at 7 PM on Friday night if you know that you’ll be tempted by friends wanting to hang out.

- Use calendar and to-do tools. Many students find that calendars, planners, and to-do lists can make them more productive. If you haven’t already, experiment with these. We’ll talk more about these time-management tools in the next section.

- Focus on your longer-term goals when your motivation is lagging. Visualize yourself earning an A in that tough class, walking across the stage at graduation, or earning your first paycheck in the career of your dreams.

- Visualize yourself studying well. Focus on how great you’ll feel after studying.

- Stay on top of your courses. Slipping behind will increase your stress level and may also hinder your understanding of course concepts. If you allow yourself to start slipping behind, telling yourself you’ll have more time later on to catch up, just the opposite will happen. You’ll be creating more and harder work for yourself in the future. Once you get behind, you’ll lose momentum and find it more difficult to understand what’s going on in the class.

What if you’re struggling?

- Revisit your planner if you’re feeling overwhelmed and stressed because you have too much to do, Sometimes it’s hard to get started if you keep thinking about other things you need to get done. Review your schedule for the next few days and make sure everything important is scheduled, then relax and concentrate on the task at hand. If there are a lot of small things that you need to do that keep popping into your head while studying, have a notebook where you can write down your “to dos” as you think of them, and then focus on your priority in the moment.

- Do one thing well. You can only focus on one priority at a time. Multitasking doesn’t work and the costs of switching tasks decreases your cognitive ability. (See Multicosts of Multitasking.)

- Ask for support. If you’re really struggling, don’t hesitate to ask for help or search for resources. Reach out to your professor or another student in the class to help get back on track. You can make an appointment with a tutor at the Learning Center, visit the Instructional Support Lab, or talk to a Student Success Advisor to get help understanding assignments or support for a personalized time-management plan. As an AUM student, you can also make a free appointment with a counselor with Counseling and Health Promotion Services if you are struggling with stress, anxiety, or depression. All AUM resources are listed at the beginning of this book.

- Just say no. Always tell others nearby when you’re studying, to reduce the chances of being interrupted. Still, interruptions happen, and if you are in a situation where you are frequently interrupted by a family member, spouse, roommate, or friend, it helps to have your “no” prepared in advance: “No, I really have to be ready for this test” or “That’s a great idea, but let’s do it tomorrow—I just can’t today.” You shouldn’t feel bad about saying no—especially if you told that person in advance that you needed to study.

- When you have competing priorities, remember your long-term goals. You may need to work, but you also want to finish your college degree. If you have the opportunity to work overtime, consider whether you’ll be able to make up that study time.

- Minimize commuting time. If you are a part-time student taking two classes, taking classes back-to-back two or three days a week takes less time than spreading them out over four or five days. Working four ten-hour days rather than five eight-hour days reduces time lost to travel, getting ready for work, and so on. You might also consider listening to course materials or relevant podcasts as you drive.

Time-Management Tips for Students with Family Responsibilities

- Talk with your family. Living with or caring for family members often introduces additional time commitments. Discuss your goals with them and get their support. Discuss that changes will occur. Discuss your need to study and ask for their help in helping you achieve your goals, which most likely will benefit your family too.

- Schedule your academic work well ahead and in blocks of time you control. You may need to use the library or another space to ensure you are not interrupted or distracted during important study times. Don’t assume that you’ll be “free” every hour you’re home, because family events or a family member’s need for your assistance may occur at unexpected times.

- Schedule your study time based on family activities. If you face interruptions from children or siblings in the early evening, use that time for something that takes less focus like reviewing class notes. When you need more quiet time for concentrated reading, wait until they’ve gone to bed or when another friend or family member can be the primary caregiver for the children.

- Enjoy your time together, whatever you’re doing. You may not have as much time together as previously, but cherish the time you do have—even if it’s going on a short walk or playing a game together. Many students feel pressure to give as much of their time to their family as they did before they were students. This pressure can lead to you staying up late to study and not sleeping enough, which is not sustainable. Being a good family member while also being a student is possible, but requires effective time-management. Focus on your family during family time and focus on studying during studying time.

- Ask for support. Remember, something, somewhere has to give. The day doesn’t include enough hours for you to work full-time, study full-time, do all the household chores, be a family member, and take care of yourself. Prioritize what you need to do each week, and, with your family, come up with a plan where everyone contributes so that everything can get done.

- Be creative with care for children and other family members. Explore options, possibly involving extended family members, sitters, other siblings, as well as child- or eldercare centers. After a certain age, you may be able to take your child or sibling along to campus, if there is somewhere the child can read or study quietly. At home, let your child have a friend over to play with. Network with other older students and learn what has worked for them. Explore all possibilities to ensure you have time to meet your college goals. Keep in mind that achieving your academic goals will be good not just for you, but also for your family.

Time-Management Tips for Student Athletes

Student athletes often face intense time pressures because of the amount of time required for training, practice, and competition. During some parts of the year, athletics may involve as many hours as a full-time job. Athletic schedules can be grueling, involving weekend travel and intensive periods of time. You may be exhausted after workouts or competitions, which may affect how well you can concentrate on academics. Students on athletic scholarships often feel their sport is their most important reason for being in college, and this priority can affect their attitudes toward studying. For all of these reasons, student athletes face special time-management challenges. Here are some tips for succeeding in both your sport and academics:

- Be a good teammate. Progress towards graduation is vital to your athletic eligibility. Many athletic teams set team GPA goals, so make sure to do your part.

- Plan ahead. Make sure your academic planner includes academic deadlines AND your athletic practice and game schedule. If you have a big test or a paper due the Monday after a big weekend game, start early. Working ahead will also free your mind to focus on your sport.

- Accept that you have two priorities—your sport and your classes—and that both come before your social life. If it helps, treat your classes (or your sport) as your job; you have to “study” and “practice,” just as others have to “go to work.”

- Ask for support. Talk to your coach. Ask older student athletes how they manage their time. Visit the Learning Center (2nd floor AUM library) or Instructional Support Lab (Goodwyn Hall). Be proactive in seeking help if you’re finding course concepts confusing.

Strategies to Put off Procrastination

“Procrastination is an emotion regulation problem,

not a time management problem.” – Dr. Tim Pychyl (Click here for more.)

| Optional Activity #2: Reflect and Discuss

Think, pair, share. First think these questions by yourself, then pair up and talk to someone else about them, and finally, we’ll share as a class.

|

Procrastination is a way of thinking that lets one put off doing something that should be done now. Procrastination can happen to anyone at any time. It’s like a voice inside your head keeps whispering brilliant ideas for things to do right now other than studying: “I really ought to get this room cleaned up before I study. I’ll study better in a clean room.” or “I can study anytime, but tonight’s the only chance I have to do X.” That voice is also very good at rationalizing: “I really don’t need to read that chapter now; I’ll have plenty of time tomorrow at lunch . . . . ”

When you’re vacuuming instead of studying for a test, ask yourself whether you’re in motion or taking action. Consider reading the article “The Mistake Smart People Make: Being in Motion vs. Taking Action” about the difference.

Procrastination is very powerful. Some people battle it daily, others only occasionally. Most college students procrastinate often, and about half say they need help avoiding procrastination. Procrastination can threaten one’s ability to do well on an assignment or test.

People procrastinate for different reasons. Some people are too relaxed in their priorities, seldom worry, and easily put off responsibilities. Others worry constantly and that stress keeps them from focusing on the task at hand. Some procrastinate because they fear failure; others procrastinate because they fear success or are so perfectionistic that they dread starting and doing something imperfectly. Some are dreamers. Many different factors are involved, and there are different styles of procrastinating.

Just as there are different causes, there are different solutions for procrastination. Different strategies work for different people. The time-management strategies described earlier can help you avoid procrastination. Because procrastination is a psychological issue, some additional psychological strategies can also help. Do you procrastinate? Reflect and try to identify why. Whatever the reason may be, procrastination is not a good idea. It often leads to stress, which can take a toll on the health of our bodies.

How do you avoid procrastination?

- Focus on your goals. Aren’t they bigger than the reasons behind your procrastination? Realize that you may never “feel like” doing an assignment or studying for an exam.

- Know what motivates you. This might be focusing on the positive, like how great you’ll feel when you’ve accomplished this difficult task, or it might be thinking of a negative consequence of procrastinating, such as the stress you feel, missing out on weekend plans, or failing a test.

- Get started. As we have already mentioned, this is the hardest part to do, but it will have the biggest effect on defeating procrastination. Find a do-able part of the project. It can be simple: skim the chapter you have to read, outline the paper you have to write, or do the first math problem. The rest of it will be easier once you get started.

- Give yourself permission to do imperfect work. Remind yourself you can improve it later once you have a draft of the assignment or paper.

- Establish and rely on a process. Figure out what works best for you and work to establish studying habits. Take some time to make a plan, list, or outline that allows you to see what you will do and when to complete your assignment or goal.

- Challenge yourself to meet fake, early deadlines. If the paper is due in six days, tell yourself it is due in two days. Knock it out early and then enjoy not having it over your head. Fake deadlines are less stressful. And if you do end up needing more time, you have a cushion.

- Study with a motivated friend. Form a study group with other students who are motivated and won’t procrastinate along with you. You’ll learn good habits from them while getting the work done now.

- Get support. If you really can’t stay on track with your study schedule, or if you’re always putting things off until the last minute, talk to a college counselor. They have lots of experience with this common problem and can help you find ways to overcome this habit.

- Take it one day at a time. Since procrastination is usually a habit, accept that and work on breaking it as you would any other bad habit: one day at a time. Know that every time you overcome feelings of procrastination, the habit becomes weaker—and eventually you’ll have a new habit of being able to start studying right away. Visualize this as walking through a forest. It’s easier to go down the well-worn path. When we break a bad habit such as procrastination, it’s like making a new walking path. It’s very hard at first to walk over the tall grass and create a pathway. The more you do it, the easier it is. It may feel easier for you to put off working on an assignment than to tackle it head-on, but the more you do it, the easier it becomes to walk that path.

- Don’t break the chain. When Jerry Seinfeld was trying to make it as a comedian, he developed a system to prevent procrastination. To write better jokes, he thought he should write jokes every day. He used a big wall calendar that showed a whole year on a page and a red marker. He would mark each day he wrote jokes with a big red X. After a few consecutive days, he had a chain. And then the task became not breaking the chain. His system is called Don’t Break the Chain and can be very motivating. You may be skeptical of this method but give it a try. It can be very satisfying to see a visual representation of your hard work and dedication.

- Eat the frog.

“If you eat a frog first thing in the morning,

the rest of your day will be wonderful.” – Mark Twain

Nobody is suggesting that you actually consume a frog, but the point Twain makes is paramount to overcoming procrastination. He meant if you have to do something you don’t want to, the best thing to do is do it right away: get it over with so you can move on to enjoy the things you want to do.

Continue Your Learning:

- “Why You Procrastinate (It Has Nothing to Do with Self-Control)” by Charlotte Lieberman, New York Times, March 25, 2019. Lieberman explains that procrastination is “a way of coping with challenging emotions and negative moods induced by certain tasks — boredom, anxiety, insecurity, frustration, resentment, self-doubt and beyond.”

- “The Surprising Habits of Original Thinkers” by Adam Grant. In this TedTalk, Grant discusses the dangers of precrastination and procrastination and argues that the most creative ideas result from avoiding both.

As you enter college, you’ll need to assess your time management strategies and may need to learn new ones. You’ll also want to be honest with yourself about your tendency to procrastinate. You’ll go through this assessment process at many points in your life when you make a major change, such as when you begin a new job or when you become a parent. With any major change, you’ll most likely need to re-assess, refine, and develop new strategies.

Continue to learn tools that will help you achieve your goals. If you meet someone who manages time well, ask what strategies they use and try them out. Be curious and keep trying new strategies so that you can optimize your efforts to succeed in college.

Warhawk Wisdom:

Time management is hard, but is key to achieving your goals. Be honest in assessing how you can improve and experiment with the strategies explained here. When you’re discouraged, remind yourself to persevere. Use your vision of your future as motivation.

Journal Prompts:

- Who are you now?

- How well do you manage your time?

- Which of the tips in this chapter related to time management do you already use?

- Which of the tips in this chapter related to procrastination do you already use?

- What types of tasks do you avoid?

- What do you do when you’re procrastinating? (Very often your avoidance techniques are productive, but not related to what you should be doing.)

- Who would you like to be?

- How would you feel if you didn’t procrastinate?

- What other benefits might you experience if you didn’t procrastinate?

- Who are you becoming?

- What tips would you give other students about time management?

- What is something you need to do that you are procrastinating about ? (Or that you think you will procrastinate about?)

- What specific strategy will you use to combat procrastination?

- What SMART goal can you set related to time management?