12

The AMA Interview for Prof. Kartik Nayak at Duke University

Kartik Nayak; Xinyu Tian; Yinhong (William) Zhao; Lunji Zhu; and Luyao Zhang

Metadata:

Medium Article URL: https://medium.com/sciecon-ama/how-does-decentralization-support-privacy-preserving-insights-on-consensus-in-the-presence-of-bab673ca2553

Interviewee: Prof. Kartik Nayak

Interviewer: Xinyu Tian, William Zhao

Executive Editors: Zichao Chen, Xinyu Tian, Lunji Zhu

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang

Resources:

YouTube Documentary: [URL]

https://youtu.be/yxM_LvNxYN8

I.About Prof. Kartik Nayak

Figure 1: Prof. Kartik Nayak

Introduction to Prof. Kartik Nayak:

As an assistant professor in Computer Science at Duke University, Prof. Kartik Nayak works in the area of applied cryptography and blockchains. He is currently focusing on two research topics:

1. Robust and efficient design of blockchain protocols.

2. Efficient privacy-preserving computation.

II.Question 1

Xinyu:

What is your motivation for doing research about cryptography and blockchain?

Figure 2: Blockchain & privacy

Prof. Nayak:

Preserving data privacy and trust decentralization.

We have been moving to use the cloud more and more in the last couple of decades. This has resulted in privacy concerns for our own data. Also, in the last 15–20 years, we have increasingly moved to being privacy-aware. That brings my interest in applied cryptography and more specifically in privacy-preserving computation.

With respect to blockchain, the idea behind it is to decentralize trust. Currently, you are placing trust in a small number of parties, which may be individual companies or financial institutions. In an ideal world, you may not want to trust one or a few numbers of parties, and you may want to decentralize it as much as possible, provided that you can have all of the benefits that you have in a centralized world. So far as you can keep the benefits the same and you can reduce the amount of trust.

III.Question 2

Xinyu:

Can you briefly highlight your research in the field of Fintech or blockchain?

Prof. Nayak:

In terms of blockchains, my focus has been primarily on designing better consensus protocols[8]. As you know, in blockchains, you decentralize trust by having multiple parties instead of one. If you have multiple parties doing the same job for you, it is essential for them to agree on whatever they’re doing. So, if you are executing a smart contract, like a bank executing a check or a post-dated check, you’re writing a smart contract, which is a program that does the same as what a post-dated cheque would do. But now it is not one institute that you’re trusting: you have a group of parties all of whom are doing the same thing.

This agreement problem has been known for the last 40 years. It started with Leslie Lamport, Shostak, and Pease [9] and it was called the Byzantine Generals Problem[10]. There have been protocols that have existed for a long time. Then you’re trying to do this at scale for every small transaction, e.g., for every payment, at that point, it becomes critical that we have systems that can, on the one hand, be efficient, and on the other, can tolerate a large number of faults.

Figure 3: The Byzantine Generals’ Problem

So, looking at different realistic models under which you can actually achieve this, is something that has been my focus. Recently, one of the streams that I worked on is the following: when research started in this space, there were these two assumptions that people made: one is called consensus in the presence of asynchrony[11], and the other is called consensus in the presence of synchrony[11]. The key difference between the two is whether messages arrive within a certain amount of time or not. Under asynchrony, you cannot tolerate any faults if you have deterministic protocols. There were many papers that came up and spoke about using synchrony and good network conditions. But these papers were not very much for practical use, they were fairly theoretical. The research since then, so this is from the 1980s until, maybe I would say 2010 or 2015, has been in the partially synchronous setting. Going back, when they learned that you cannot do anything with deterministic asynchronous protocols, people went two routes: use a randomized asynchronous protocol or come up with a notion that is intermediate between synchrony and asynchrony?” And all of the research in the space has evolved to use these modeling assumptions. One of the most known assumptions is the pBFT or practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance[12], which was by Barbara Liskov[13] and Miguel Castro in the year 2000. There are better practical variants of these protocols in the same model but the number of faults they can tolerate is few. You can only tolerate one-third of Byzantine faults. There are lower bounds to say you cannot do any better.

But in an ideal world when you want to tolerate as many faults as possible. So, I think the change happened actually with Bitcoin where Bitcoin assumed synchrony and still made things work. While most people thought of synchrony as being impractical, Bitcoin said, well, you can have a system that works in practice. There were many other things that Bitcoin was doing, but that was one of those assumptions. This goes back to the 2016 or 2017 timeframe when we went back and said well Bitcoin assumes synchrony, whereas all of the practitioners assume asynchrony in practice.

Figure 4: Demystifying Cryptocurrency

One of my streams of research that I focused on is to go back and see what can you do with synchronous protocols. The advantage is clear: instead of targeting one-third Byzantine fault, I can tolerate minority collusion of 49% faults, which is great. But the question is, you still go back and keep asking those questions: “Is it practical? What does it take to make it practical?” For instance, with synchrony, the difference is that my protocol needs to know how much time it takes for a message to be sent, and this time-bound is fixed, known and no message should break it apart. If I say it takes one second for my message to reach, even if one message breaks, my output will slow for just one minute. So all bets are off, that can be terrible. If you just design a regular synchronous protocol without taking into consideration these things, they could happen once in a while, and then you do not have safety. What can we do to make it work under worse network conditions? What if there is a small degree of asynchrony for whatever definition of small degree that we can achieve while ensuring that we can still tolerate Byzantine faults? I think that has been one key area of focus of my research among others.

IV.Question 3

William:

How do you think the Internet Computer can possibly empower your research? What support do you need to innovate with Internet Computer? If you have any technical questions for Dfinity engineers, you can also ask and we may refer your questions to Dfinity engineers for more conversation.

Figure 5: DFINITY Internet Computer

Prof. Nayak:

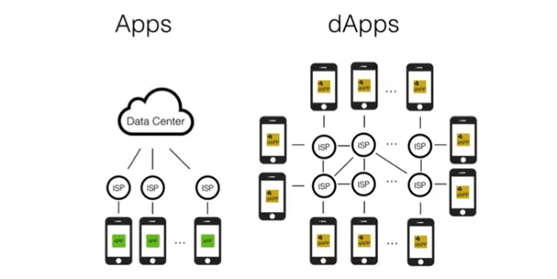

Figure 6: Regulation of Decentralized Application

I think my questions will be more generic, not specifically for Dfinity but definitely applicable to Dfinity as well.

It is always nice to say we want decentralized trust. But I think understanding what it means in practice and how it matters, so you know how this decentralization matters may be the key. For example, one of the key uses that are touted in the blockchain is this idea in supply chain management[14]: if I have blockchains I have a better degree of protection compared to doing it in a centralized way. The question is: Can we precisely show the advantage of using a blockchain?

The question is, in many of these use cases where we say we want decentralization, do we really, really, really need decentralization? Or it is just acting as a catalyst towards changing the system? Are we just asking for a different system temporarily and 10 years later we will move back to a centralized system again because it has many advantages?

So long story short, I want to ask what are the three killer use cases that you think can be solved by an Internet computer. Well, if I ask you to compare Dfinity to, let’s say Ethereum, that may be actually an easier comparison. Because one can just say I can give you better performance, and so on. I think the comparison point to me is between Dfinity Internet Computer and the centralized system today. If you say you need the decentralized application, why do you need it and, what are the three killer applications that will be useful?

And for these applications what are the requirements? Do you need blockchain or do you need something else that may not require all of the features of blockchain? As a simple example, for payments, bitcoin uses consensus, and many of these consensus protocols use consensus. You agree, and then you do payments. So recently there has been a sequence of works, They say if all you want to maintain is these payments, you actually don’t need consensus as a stepping stone. You can achieve this without an ordered sequence of transactions. There are ways of doing it, so the question is, do you need what you’re building and why do you need it?

William:

Thank you, Professor, that’s really great insight and a very sharp question that we will ask the Dfinity engineers and we really appreciate your answering our questions, and we really appreciate the introduction and inside you provide us today. Thank you! That’s all for our interview.

V.Relevant Materials

[1] Privacy-preserving computation

Secure multi-party computation (also known as secure computation, multi-party computation (MPC), or privacy-preserving computation) is a subfield of cryptography with the goal of creating methods for parties to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private.

[2] Secure processor

A secure cryptoprocessor is a dedicated computer-on-a-chip or microprocessor for carrying out cryptographic operations, embedded in a packaging with multiple physical security measures, which give it a degree of tamper resistance. Unlike cryptographic processors that output decrypted data onto a bus in a secure environment, a secure cryptoprocessor does not output decrypted data or decrypted program instructions in an environment where security cannot always be maintained.

[3] Obvious computation

An oblivious computation is one that is free of direct and indirect information leaks, e.g., due to observable differences in timing and memory access patterns.

[4] I/O efficiency

I/O-efficient algorithms are algorithms designed in a two-level external memory (or I/O-) model, where the memory hierarchy consists of the main memory of limited size M and external memory (disk) of unlimited size; the goal is to minimize the number of times a block of B consecutive elements is read (or written) from (to) disk (an I/O-operation, or simply I/O).

[5] Bandwidth

The maximum amount of data transmitted over an internet connection in a given amount of time.

[6] Locality

In computer science, locality of reference, also known as the principle of locality, is the tendency of a processor to access the same set of memory locations repetitively over a short period of time. There are two basic types of reference locality — temporal and spatial locality. Temporal locality refers to the reuse of specific data and/or resources within a relatively small time duration. Spatial locality (also termed data locality) refers to the use of data elements within relatively close storage locations. Sequential locality, a special case of spatial locality, occurs when data elements are arranged and accessed linearly, such as traversing the elements in a one-dimensional array.

[7] RAM

Random-access memory (RAM) is a form of computer memory that can be read and changed in any order, typically used to store working data and machine code. A random-access memory device allows data items to be read or written in almost the same amount of time irrespective of the physical location of data inside the memory, in contrast with other direct-access data storage media (such as hard disks, CD-RWs, DVD-RWs, and the older magnetic tapes and drum memory), where the time required to read and write data items varies significantly depending on their physical locations on the recording medium, due to mechanical limitations such as media rotation speeds and arm movement.

[8] Consensus Protocols

In addition to cryptography and P2P (peer-to-peer) technology, consensus protocols are also a fundamental part of blockchain technology. A good consensus protocol can guarantee the fault tolerance and security of the blockchain systems. The consensus protocols currently used in most blockchain systems can be broadly divided into two categories: the probabilistic-finality consensus protocols and the absolute-finality consensus protocols.

[9] Leslie Lamport

Leslie B. Lamport (born July 2, 1941) is an American computer scientist. Lamport is best known for his seminal work in distributed systems, and as the initial developer of the document preparation system LaTeX and the author of its first manual. Leslie Lamport was the winner of the 2013 Turing Award for imposing clear, well-defined coherence on the seemingly chaotic behavior of distributed computing systems, in which several autonomous computers communicate with each other by passing messages. He devised important algorithms and developed formal modeling and verification protocols that improve the quality of real distributed systems. These contributions have resulted in improved correctness, performance, and reliability of computer systems.

[10] Byzantine Generals Problem

The Byzantine Generals Problem is a term etched from the computer science description of a situation where involved parties must agree on a single strategy in order to avoid complete failure, but where some of the involved parties are corrupt and disseminating false information or are otherwise unreliable.

[11] Consensus in the presence of asynchrony and consensus in the presence of synchrony

In the standard distributed computing model, the communication uncertainty is captured by an adversary that can control the message delays. The communication model defines the limits to the power of the adversary to delay messages. There are three basic communication models: the Synchronous model, the Asynchronous model, and the Partial synchrony model.

In the Synchronous model, there exists some known finite time-bound ∆. For any message sent, the adversary can delay its delivery by at most ∆.

In the Asynchronous model, for any message sent, the adversary can delay its delivery by any finite amount of time. So, on the one hand, there is no bound on the time to deliver a message but, on the other hand, each message must eventually be delivered.

[12] Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance is a consensus algorithm introduced in the late 90s by Barbara Liskov and Miguel Castro. pBFT was designed to work efficiently in asynchronous(no upper bound on when the response to the request will be received) systems. It is optimized for low overhead time. Its goal was to solve many problems associated with already available Byzantine Fault Tolerance solutions. Application areas include distributed computing and blockchain.

[13] Barbara Liskov

Barbara Liskov (born November 7, 1939, as Barbara Jane Huberman) is an American computer scientist who is an Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Ford Professor of Engineering in its School of Engineering’s electrical engineering and computer science department. She was one of the first women to be granted a doctorate in computer science in the United States and is a Turing Award winner who developed the Liskov substitution principle.

[14] Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management is the management of the flow of goods and services and includes all processes that transform raw materials into final products. It involves the active streamlining of a business’s supply-side activities to maximize customer value and gain a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

VI.Acknowledgments

Interviewee: Prof. Kartik Nayak

Interviewer: Xinyu Tian, William Zhao

Executive Editors: Zichao Chen, Xinyu Tian, Lunji Zhu

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang