15

An interview with Prof. Olivier Marin on blockchain, consensus mechanism, and distributed system.

Olivier Marin; Jiasheng (Ray) Zhu; Xinyu Tian; Zichao Chen; Lunji Zhu; and Luyao Zhang

Metadata:

Medium Article URL: https://medium.com/sciecon-ama/prof-olivier-marins-views-on-the-consensus-mechanism-of-blockchain-b6d8eb643d00

Interview: Prof. Olivier Marin

Interviewer: Ray Zhu

Executive Editors: Zichao Chen, Xinyu Tian, Lunji Zhu

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang

I.About Professor Olivier Marin:

Figure 1: Professor Olivier Marin

Mr. Olivier Marin is a Professor of Practice in Computer Science at NYU Shanghai. Marin received his Ph.D. in Computer Science in 2003 from the Universite du Havre, France. Marin is an expert in Operating Systems. His current research focuses on distributed middleware[1] solutions for dependability in various environments: delay-tolerant networks[2], clouds[3], and P2P networks[4]. And his research interests include fault tolerance[5], recommendation systems[6], multi-agent systems[7], and distributed architectures[8]for the management of Big Data.

II.Question 1

Ray Zhu:

What is your motivation for doing fintech/blockchain research?

Prof. Marin:

I’m not interested so much in fintech, but very much so in blockchain technology for very simple reasons. I’ve been working since my Ph.D. on what we call fault tolerance in distributed systems.

Distributed systems are any type of computer system that you use, where not only one machine is involved, but several machines. When we are discussing a blockchain infrastructure, which is not just the machine in front of you, it also includes other computers playing different roles. Some of them are miners, some of them hold the ledgers, some of them validate or do stuff like that. Inherently, a blockchain is such a distributed system.

I said I’m interested in fault tolerance in distributed systems. So what is fault tolerance? Fault tolerance happens when you have several computers — for sure, the more computers you have involved, the higher the likelihood that one of them is going to do something wrong. It doesn’t need to be malicious. It can be that the computer just dies, it happens. Maybe someone cuts the power, or it simply breaks.

So, my work in research from the start was: how I can guarantee with all of these machines working together, that if one of them or several of them die at the same time, how can I make sure that the rest of the system can still survive this.

There is a specific theoretical area in my domain that is called consensus [2]. I’m pretty sure that if you’ve read any material on blockchain and fintech, you’ve come across that word. Consensus is a specific theoretical construct that allows several participants to agree on something they want to reach a common value decision. Now we’ve had theoretical papers answering the question of how you can reach a consensus after decades of development in computer science research. In particular, the research question is: Is consensus reachable? We even have theoretical proofs that, in many situations, a consensus is not reachable. That’s where I’m particularly interested in blockchains because they are used as technological support for financial applications.

But as a fact, fintech’s claim about its 100 % reliability is not true, as proven in the theoretical papers. It cannot be true. Because underneath the theoretical mathematics of it, all say that there are moments where I could destroy the blockchains. If I can have all of the computers, I can switch off the power to all of these computers. It’s over! You don’t have your blockchain.

Luckily enough, the idea of a blockchain is that the probability that all of your computers die together is very low. So, what I’m interested in is, what are the boundaries? What is it that makes it so that the blockchain can survive? What kinds of failures, to what degree does this survival work?

But one thing is sure: Normally, if at least half of the machines are malicious, you cannot have a consensus, or at least you cannot have an honest consensus. The initial Bitcoin paper already talks about the 51 % attack. The fact that if one entity controls more than half of the network, it’s over. There’s no way you can build anything that you can trust.

Now, we’ve moved this towards a different setting with plenty of different machines, but no one specifically owns all of the machines. I’m also interested that when you have one entity that controls everything, what should you do to guarantee that you’re still going to trust the results?

So what’s my motivation for doing research about blockchain? Because blockchains are built on top of my area of interest.

2. If you have 100 computers and maybe several of them break down anyway. I wonder how you can tell which ones are broken and which are not. For instance, 80 % of the computers give the same result, and the rest remaining 20 % give a different result. Although the probability is very low, I think it’s also possible that 80 % of computers’ results are wrong, right?

Figure 3: Consensus mechanism in blockchain

Prof. Marin:

It’s a great question. We have a foundational paper in my domain called FLP 85. It was written by Fischer, Lynch, and Paterson in 1985 (“Impossibility of Distributed Consensus with One Faulty Process”), hence FLP 85. The paper talks about the impossibility of consensus, even between two machines when the system is asynchronous. Asynchronous means that there is no time-bound between the sending and the reception of a message if I want to put it really simply. It’s a bit more complicated, but that’s the gist of it.

Give you an example. Let’s say that you’re talking to me regularly. And, suddenly, you stop speaking for 20 seconds. You just sat there, looking at me. I’m going to start getting worried, right? I’m going to call you by your name, say, hello, are you there? You might keep on not answering me. How do I know? How do I make the difference between you’re playing a joke on me, you just pretending not to be able to talk to me, and you being dead?

The answer is, I can’t make the difference. If I walk over to you and I listen to your heartbeats, and then I can say you’re alive. But when we are two separate machines, the machine can’t walk over and listen to the heartbeats. The result of this paper says it’s a network where I don’t have a bound on the time that it takes to send a message. If someone stops talking to me, I can never decide whether they’re malicious or whether they’re just slow.

What does that mean? It means that in order to make a decision, I need to wait until they talk to me again until I get communication that shows me that they’re alive. However, maybe the consequence is that I have to wait an infinite time to hear from you and make a decision. That means I cannot potentially make a decision. Therefore, coming back to your 20% vs. 80% question, the answer is there’s no way we can answer.

In a real-life situation, messages get lost, computers break. Sometimes messages get routed a long way, and they will come, and you just have to wait. If that were true, we would have no internet! So lucky fair enough: we cheat. What we do is we put a boundary arbitrary time limit. After, let’s say, 10 seconds (if I still don’t receive messages from a machine), I’m going to decide it’s not talking to me, fair enough. I might be making the wrong decision. Because maybe, at the 11th second, it’s going to send me the message.

Figure 4: 51% attacks in the blockchain

Now, I’m in a situation where I have 10 machines, 8 of them will answer me and 2 of them will not. That’s kind of fine because if I wanted to make a decision, I only care if at least half of them talk to me. If I get 5 answers, I know that I have a majority of machines. If they’re all the same and they all agree with me, that makes 6 out of 11. Whatever the others might say, they’re going to be wrong because they are the minority. If I say that more than half of the nodes can be malicious, if I have a vote of 6 machines, including me, we might all be the malicious machines. And this is the 51 % attack when we are malicious and are controlling the system.

So, back to how you formulated your question, basically, you laid out what happens when we try to build a consensus: we have to accept that some machines might not answer. And we have to accept that every time the decision we reach is not fair proof. That’s why I can say that for those fintech solutions, theoretically, they cannot claim to be 100% reliable. It’s a system about trust.

III.Question 2

Ray Zhu:

Can you briefly highlight your research in the field of fintech/blockchain?

Prof. Marin:

#1 Project: A decentralized system with a “reputation” rating

I have three interesting projects. The first one, I’ve already published a bit on that topic, but not specifically with blockchain. It’s in the Oxford Computer Journal of Oxford (“ASCENT: A Provably Terminating Decentralized Logging Service”). We wanted a system that would maintain a ledger that is completely distributed, with no centralized server, no entity that’s in the middle, and that decides everything. We share everything with plenty of machines. We want to make sure that when a transaction is being done with two machines trying to make a transaction, we keep track of that transaction, and none of the machines can go back to deny what they have pledged. And afterward, we can actually show that all of these have been recorded by a majority of machines, so we never lose this. Now you might think it’s blockchain. But we didn’t do it in a blockchain. We made another type of system, a peer-to-peer system.

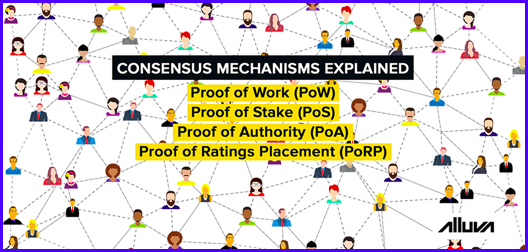

So we have the first part: building a ledger. And the point was that a blockchain relies on the proof-of-work, proof-of-stake, or many other ways to do it. But anyways, that works when everyone has a vested interest in upholding the system because they’ve put money or put work or labor into creating the values.

But the thing is, it works until a given point because of what we just discussed in the previous question. What happens when I have a majority of liars? The system I worked on for that paper was not built with all of the machines being equal because the problem with this majority attack is the machines are equally performing. If I have proof-of-work, the miners will all have an equal chance of finding the numbers and of gaining that.

However, there is another type of distributed system called reputation system. This is another area that I am interested in. Reputation systems are what we have in Taobao: when you buy from someone, you look at the rating. We look at the number of hearts, diamonds, or crowns. You may not be worrying about the good quality if the vendor has golden crowns. This is not entirely distributed because it has Taobao that centralizes the rating of the vendors. However, the cool thing is you have plenty of transactions all the time.

What we built was as you have transactions inside the distributed system, you’re going to rate the other machines. And the ratings are going to tell you, is that a machine I can trust? If it’s a machine I can trust, I will give it more possibilities of having more transactions. Hence, the system is built more on trustworthy machines rather than on all machines.

But then we have a different type of problem. We’ve solved the 51% problem, but now you can still subvert the system if you gain enough of a reputation. So we need a way to assess the reputations in a scheme that someone cannot cheat with. So in that particular paper, we use reputations to build blockchains with the ledger only with the machines you think are trustworthy. That is the first area.

#2 Project: Quick payments verified by witnesses on the blockchain

Figure 5: Witnesses and proofs on the blockchain

The second area is still in development, and I have discussed this with Yulin. This idea came to me because I was trying to pay with Alipay in a supermarket once, and I didn’t have any network connectivity. I didn’t have any cash either. The cashier was nice enough that he allowed me to go elsewhere, caught a QR code, and ran back quickly to pay. This story shows that, unfortunately, even with centralized payments, sometimes you can’t connect and pay.

Let’s go back to the blockchain. There are now actually 2 Bitcoin systems. One is Bitcoin, and the other is BitCash. The Bitcoin system is not made for that kind of transaction because it accepts validated transactions over a longer period to be trustworthy. But BitCash is exactly for that kind of payment.

BitCash built a parallel system on the blockchain, where the number of transactions is much bigger. So it means a bigger throughput, and so blocks get mined much faster, and you don’t have to wait for an hour long. Although you may have quick payments, it doesn’t alleviate the fact that if it goes faster, you can still cheat because there’s a point where sometimes the network is not accessible.

When the vendor cannot certify that you can pay, there are two ways they might say. For one, they’re going to say you can’t pay. For the other, they’re going to trust you for a given amount of time. Especially in China, if you cheated, the police are going to catch you. In general, that’s how it works. In other countries, it might not work that way.

So as I said before, we’re trying to work on the boundaries, we’re trying to see what are the minimum requirements to allow for a direct payment system on your phone that would use the blockchain, but only once you connect back. So when you pay someone, if you don’t have access to the internet, the vendor and other buyers keep track of what they’ve done the event. And when they go back to connectivity, they will send this and notify the ledger and confirm that this happened.

However, there may be a problem here: it’s one word of someone against the word of the other. However, we could reinforce this. We could have witnesses when I am out of connectivity from 5G or Wifi, and maybe I still have other people who have phones nearby. When I have the transaction, I could send a token saying, look, the transaction took place. If I have enough people as witnesses, they can walk away and then verify this transaction. It is like a tiny reputation system on a local scale for the purpose of quick payments. So, this is the second project I’m working on.

#3 Project: Innovative education on blockchain-an integration of CS & ECON

Figure 6: Blockchain innovation education

In the third project, we are working with Professor. Elaf ElliotIlaf Elard to build a course on blockchain technology. It’ll be a mix of economics students and CS students.

I’m not an expert in economics or finance. I honestly don’t understand why anyone would want to use a cryptocurrency based on the blockchain. Specifically, for the reasons I gave you, I do not trust consensus because I know what consensus is. So I would never put my money there, ever! But still, you can see that the rates fluctuate a lot for several reasons. Elon Musk comes around and suddenly breaks the system. But people do invest, and there is actually value created. I cannot understand why this happens.

But what the economics students could gain is an understanding of the underlying technology so that when they make financial or economic decisions, they understand why. Because blockchains right now, in my opinion, are a buzzword. If you go to any fintech company, they use “blockchain”, even when they just have four machines, they say blockchain. Because then investors are going to give them cash.

So, I really want students to be aware of the technology and the economy behind it, so that they can make informed decisions. The research itself is how we can create pedagogical tools that describe all of those complicated notions, such as consensus, double-spending [10], public key, etc. Can we reduce them to something easy to understand for students who don’t want to major in computer science but still want to understand the general idea behind it? There are two tracks we’re working on. One is about how double-spending works. The second one is about how blocks are minded and how they are chained next to each other, including why it works, why you have a ledger, and how it is built.

IV.Question 3

Ray Zhu:

How do you think the Internet Computer can possibly empower your research? What support do you need to innovate with the Internet Computer? What technique questions do you have for the DFINITY engineers?

Figure 7: Dfinity and Internet computers

Prof. Marin:

The research I’m interested in is built on a theoretical prototype. I usually try to show that it works with my experiment. I evaluate the performance, and I look at whether my idea was worth it or not. So, the cool thing is, I don’t compete with theoretical researchers. I am in an area that I think is important for computer science, because we are not just a science. We also have an engineering portion where you write software, and you check whether it works or not. Hence, the Internet Computer can empower my research as an experimental power, as a platform to test my ideas.

Suppose I could use the blockchain that is on the DFINITY and see if I can connect it with non-connected devices, even if I simulate them and see how I can cheat with those, whether I can use what we call a man-in-the-middle attack (MITM Attack) [11], what happens between the point where I have the transaction and the moment where I insert it in the Internet Computer. So basically, I need concrete software and hardware capability that allows me to run my experiments and show whether they work or not. Even things that don’t work are also super interesting in my area. Because when they don’t work, you can show why. So that’s the answer to the first question. They can empower my research simply as they give me the capacity to come and use the machines.

Prof. Marin:

The second part is, what support do I need?

First of all, access to the platform. I’d like to access the hardware and software.

Second, fundings or people who can collaborate on my research projects are welcomed. What I also need is to propagate and discuss ideas.

We are a small institution for now in Shanghai. Experimental research, unfortunately, needs manpower. In my particular area of research, here, I’m the only one. So I’m working alone and doing experimental research alone. I can work with undergrads right now, but undergrads may not yet have all the knowledge and skill to be able to ask very tough questions because they’re on the verge of knowing how to do that. So, if I could get help with either funding or people coming to work on this particular aspect of research, that would be great. I would also like to organize some workshops, bringing colleagues from my domain to discuss these aspects and to prepare the prototypes.

Prof. Marin:

Then, the technical questions that I have for DFINITY engineers.

I co-supervised a capstone project with Prof. Luyao Zhang and Prof. Yulin Liu. The topic is to implement a stablecoin on top of the Internet Computer. The result was disappointing.

Maybe that’s because of the unstable versions of the software that we are running initially at the time of the capstone project. As you probably know, the Internet Computer is publicly open very recently. So it is great to have access to that, probably if we were doing the same thing now, maybe it would work better. And I don’t really have other exact technical questions now for the definitive engineers.

The main questions would be the following. First, what parts are actually completely stable now? Is there a clear API [5] of the Internet Computer and stable calls (the functions that we can call inside) and see exactly what they do and how they work?

Second, do we have all the technical specifications of the hardware that is underneath and of the software that is running the blockchain? If we had all this, then that would help a lot.

V.Conclusion

Supports that Prof. Marin may need from DFINITY:

First of all, access to the platform. I’d like to access the hardware and software.

Second, fundings or people who can collaborate on my research projects are welcomed. What I also need is to propagate and discuss ideas.

Prof. Marin’s questions for DFINITY engineers/developers:

What parts of the Internet Computer are actually completely stable now?

Is there a clear API of the Internet Computer? Are there stable calls (the functions that we can call inside) and can we see exactly what they do and how they work?

Do we have all the technical specifications of the hardware that is underneath and of the software that is running the blockchain? If we had all this, then that would help a lot.

VI. Relevant Materials

[1]Distributed middleware:

Middleware in the context of distributed applications is software that provides services beyond those provided by the operating system to enable the various components of a distributed system to communicate and manage data. Middleware supports and simplifies complex distributed applications.

[2]Delay-tolerant Networks:

Delay-tolerant networking (DTN) is an approach to computer network architecture that seeks to address the technical issues in heterogeneous networks that may lack continuous network connectivity. Examples of such networks are those operating in mobile or extreme terrestrial environments, or planned networks in space.

[3]Clouds

Cloud computing is the on-demand availability of computer system resources, especially data storage (cloud storage) and computing power, without direct active management by the user. The term is generally used to describe data centers available to many users over the Internet.

[4]P2P Networks

Peer-to-peer (P2P) computing or networking is a distributed application architecture that partitions tasks or workloads between peers. Peers are equally privileged, equipotent participants in the application. They are said to form a peer-to-peer network of nodes.

[5]Fault Tolerance:

What is Fault Tolerance?

Fault tolerance refers to the ability of a system (computer, network, cloud cluster, etc.) to continue operating without interruption when one or more of its components fail.

The objective of creating a fault-tolerant system is to prevent disruptions arising from a single point of failure, ensuring the high availability and business continuity of mission-critical applications or systems.

[6]Recommendation system

A recommendation system is a subclass of information filtering systems that seeks to predict the “rating” or “preference” a user would give to an item.

Recommender systems are used in a variety of areas, with commonly recognized examples taking the form of playlist generators for video and music services, product recommenders for online stores, or content recommenders for social media platforms and open web content recommenders.

[7]Multi-agent system

A multi-agent system is a computerized system composed of multiple interacting intelligent agents. Multi-agent systems can solve problems that are difficult or impossible for an individual agent or a monolithic system to solve.

[8]Distributed architecture

In a distributed architecture, components are presented on different platforms and several components can cooperate with one another over a communication network in order to achieve a specific objective or goal.

[9] Consensus:

What is Consensus?

A consensus mechanism is a fault-tolerant mechanism that is used in computer and blockchain systems to achieve the necessary agreement on a single data value or a single state of the network among distributed processes or multi-agent systems, such as with cryptocurrencies. It is useful in record-keeping, among other things.

Some examples of consensus?

proof of work (POW), proof of stake (POS)

[10] Double-spending:

What is Double-spending?

Double-spending is the risk that a digital currency can be spent twice. Unlike physical cash, a digital token consists of a digital file that can be duplicated or falsified.

How does Bitcoin solve double spending?

Bitcoin was the first major digital currency to solve the issue of double-spending. Information from blocks is added to the ledger every few minutes; all nodes on the network maintain a copy of the blockchain ledger.

[Investopedia1] [Investopedia2] [Wikipedia]

[11] : Man-in-the-middle attack (MITM Attack)

What is an MITM attack?

A MITM attack is a cyberattack where the attacker secretly relays and possibly alters the communications between two parties who believe that they are directly communicating with each other. One example of a MITM attack is active eavesdropping, in which the attacker makes independent connections with the victims and relays messages between them to make them believe they are talking directly to each other over a private connection, when in fact the entire conversation is controlled by the attacker.

[12] : API

What does Prof. Marin say about API?

“An API is what we call an application programming interface. It’s what a computer scientist or developer uses to be able with a program to use services on another program.”

What are some simple examples of API?

API is a software intermediary that allows two applications to talk to each other. Each time you use an app like Facebook, send an instant message or check the weather on your phone, you’re using an API.

VII. Acknowledgments:

Interview: Prof. Olivier Marin

Interviewer: Ray Zhu

Executive Editors: Zichao Chen, Xinyu Tian, Lunji Zhu

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang