11

Introduction and Background

Sustainability implies an incorporation of knowledge from multiple backgrounds, as sustainability problems are often complex in nature. This means that new knowledge must be created to solve the problem. Working within a group composed of individuals from different backgrounds can be an effective method of problem solving, because sustainability issues tend to involve a range of stakeholders and factors that impact social, economic and environmental issues. Collaboration is an important component of creating successful solutions to sustainability problems. It ensures that all key participants have power in decision making, and that they share the responsibility for active participation. Experts and/or stakeholders coming from different backgrounds and disciplines must identify a specific issue and create a common set of expectations to successfully work together. This chapter will explore both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research approaches, outlining each method’s ideal processes. The chapter will delve into ideal models for utilizing these methods and outline the benefits and challenges of using each method. This chapter will also explain how interdisciplinary research and transdisciplinary research differ, and when it is best to use each method depending on the situation.

In the academic world, people from within various disciplines classify and organize larger branches of academic studies. A discipline is a field of study or branch of knowledge where the people from within the discipline have a specific language and culture based on the knowledge they have and create. It is important to include knowledge and shared learning from multiple relevant disciplines to ensure all key participants have the power and responsibility to make decisions towards a solution they will be impacted by.

Interdisciplinary Research Approach (IDR)

Interdisciplinary research is a mode of research by teams or individuals within two or more disciplines that integrates data, techniques, and concepts to advance the understanding of a topic or to solve a real-world problem. IDR incorporates previous knowledge from different disciplines, but also aims to create more knowledge. When conducting IDR, there should be a generous amount of collaboration between disciplines. While disciplines will often conduct their research based on their own ideas and concepts, there must be collaboration and dependence on each other in order for IDR to be successful.

In this reader, we are focused on the concepts discussed within a sustainability framework. The following example is not an example of a sustainability challenge, rather it is provided for clarification on the topic of interdisciplinary research.

Recall that an interdisciplinary research approach is executed by teams or individuals among two or more disciplines in order to integrate information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and theories to advance understanding or to solve a real-world problem.

Consider the discovery of a new unidentified animal species: within the branch of biology, different disciplines would be used. A morphologist would classify the physical features of the animal, a taxonomist would organize its lineage into a phylogenetic tree, and an ecologist would determine its significance in the community. Environmentalists, experts in behavior, and other scientists with their own specialty in a discipline. Without all the scientists working together and contributing their information, the newly discovered species would not be fully classified.

IDR starts with the initial identification of the problem the research group is aiming to solve, as well as the formation of a group of experts striving to solve this problem. This allows for the creation of a central research question. Once the problem is defined, researchers decide how they want to study the problem and how they are going to delegate the research tasks. Most commonly, IDR is building upon previous science rather than creating entirely new knowledge. Researchers may also begin to establish sub-questions branching from the initial question and determine the methods they will be utilizing to conduct the research. The experts then progress into data collection and the initial analysis of this data. It is imperative that the data collected is unbiased. This means that the data cannot be unfairly balanced in favor of one view. After collection, the data is interpreted and applied to the problem at hand through discussion. IDR may not necessarily end with a problem being solved, but will end with the creation of new knowledge that is relevant to the research that was done.

An Interdisciplinary Research Approach is further demonstrated in the case study box below:

In the face of sustainability challenges, a lot of effort is put into sources of renewable energy. Wind Turbines harness energy from the wind and can be utilized as a source of power. However, the wind turbines are often in open areas that intersect the migratory paths of birds and bats. The animals fly dangerously close to the blades and are struck by them – many of the species are endangered.

To address the concern of bat mortality by wind turbines, renewable energy experts formed a research team that consisted of engineers and bat biologists. The biologists and engineers integrated their knowledge to address the concern to the loss of biodiversity. One of the biologists specialized in acoustics, he had an idea to create a device that would be attached to the turbine and emit a loud noise, within the hearing range of the bats, to deter them from flying near the blades of the turbine. The engineers built the device and the collaboratively tested the results. Unfortunately, the design was not effective in preventing bat deaths. However, a strong network was developed, and the participants involved are determined to find a solution, perhaps by incorporating other scientists.

It is important to note that the Interdisciplinary Research Approach explained in this reader is based on an idealized process and conceptualization. The precise details of each scenario will be context-specific.

Benefits and Challenges of IDR

Interdisciplinary work is greatly encouraged because it allows for so much more to be accomplished and learned than if there was only one discipline tackling a problem. IDR allows for the exploration of knowledge across a variety of subjects. When researchers conduct work solely within their individual disciplines, they are restricted to that discipline’s culture, language, and way of thinking. When different disciplines with different languages and cultures are included, it allows for diverse opinions and expertise, which can help further the project. With different discipline’s languages and cultures included, the information can be framed in different ways for people to understand and conceptualize. With IDR, not only do the teams/individuals’ scholarly ideas and theories come into play, but so do their views of the world, their non-academic beliefs, and personal endeavors. This can be very helpful when conducting IDR because it can be used to connect people in a way outside of academia and build stronger personal relationships which, in turn, makes the project more likely to succeed.

There are a few limitations to IDR. One challenge is all the extra time it takes to coordinate multiple disciplines and come up with a common goal. In addition, while the different languages and cultures of the disciplines can be very helpful, it also takes time and effort for people to get familiar with other people’s language and culture of their discipline. IDR can also cause uncomfortable working and researching environments because of different researchers’ beliefs or views of the world. If this discomfort goes unaddressed, it can cause lots of tension and can hinder the research or project in general. Also, interdisciplinary research is still debated in terms of whether or not it is successful or worth it, so it can sometimes be difficult for the research to be published.

Transdisciplinary Research Approach (TDR)

Transdisciplinary research is a method of research that attempts to create solutions to complex, context-specific issues through combining the knowledge and ideas of both experts and non-academic key stakeholders. There are three main aspects of TDR: 1) the problem must be socially relevant; 2) the project must allow for cooperation and collaboration between scientific disciplines and non-academic stakeholders; 3) the main goal must be to create solution-oriented knowledge that can be applied to both scientific and societal practices.

Social relevance means that the problem can apply to a situation in a society. It connects both experts and non-experts, as they both are looking to find a solution. Solution-oriented knowledge is created when research is done with the intention of applying the knowledge into action. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as by creating new regulations or by doing physical actions, such as building a structure.

A transdisciplinary approach can be divided into three main phases:

Phase A. Form a comprehensive group and define the problem

The first phase of TDR includes the assembly of a comprehensive group, or a project team, that represents those who are affected by the complex problem at hand, or who could contribute to the overall understanding of the problem. Here, initial project starters come together to decide which stakeholder groups should be involved and reach out to find representatives for each group. In TDR, the groups are composed of academic experts and non-expert stakeholders. The stakeholders involved will always be comprised of the groups or individuals that are most impacted by the sustainability problem at hand. They are often found through a stakeholder analysis. Since this is the case, each situation and team will look different, as every instance of TDR is context specific. Once the project team is created, they work together to define the problem they will be tackling. They also establish common goals and group norms, which could include a shared language and set of expectations.

This group works together to refine and agree upon the complex problem they will be looking to research and solve. This will likely be continually assessed throughout the research, as different, related research questions can arise throughout this process. Being specific about what the initial research question is allows for all groups to research cohesively and use their knowledge towards a common goal.

Both of these pieces happen together, and often build on each other. As the group grows, they can expand upon their understanding of each other’s knowledge and more accurately define what is going to be researched.

Phase B. Co-produce and share knowledge on solution-oriented information

For a project to take a transdisciplinary approach, it must include non-expert knowledge in addition to expert research. When these groups come together and research is conducted, co-production of knowledge occurs. Co-production of knowledge is when groups of stakeholders and academic experts work together to define problems and gather new information on these topics that will ultimately be used in tackling complex sustainability issues. The group must establish trust in each other and develop and understanding of different kinds of knowledge. For example, experts may contribute more generalized, scientific knowledge, while stakeholders might contribute other non-traditional types of knowledge. These can include foundational and local knowledge, such as providing a perspective on how a certain community has historically handled similar situations. It is important to note, however, that experts and non-experts are not limited in what types of knowledge they can bring to the table, and it will vary by situation. Recognizing the value in the different types of knowledge creates more well-rounded ideas and solutions.

All of the knowledge shared and created must be of value to everyone in order for all groups to utilize it. This means that the knowledge must be considered relevant to the situation and the group members must feel that they can trust it. If it is not seen this way, it will not end up being applied later. Knowledge created through co-production is more likely to be applied to social problems because key stakeholders and decision makers were involved in the process, and therefore better understand the data that was found.

Phase C. Apply co-produced knowledge to social and scientific fields

Following the analysis and interpretation of co-produced knowledge, the project team must deliberate on how to use the new data to create a solution. The project team must find a way to implement the research results by crafting a comprehensive solution and applying it to the problem. The knowledge and solution created must be able to be applied by all involved, though the application will look different between groups. For example, the experts will create literature for academia while the non-expert decision makers have the ability to implement the solution to improve the challenge they are facing, such as by creating a town ordinance.

This phase requires a continuous effort from all of the involved parties. The phase is dependent upon the support of decision-making stakeholders, as well as access to critical resources and funding. The groups of researchers must remain aware that creating the right solution may take time and multiple attempts. Often there is no one correct solution to these complex issues.

A Note about the Phases:

It is important to note that the Transdisciplinary Research Approach phases explained in this reader are based on an idealized process. The precise details of each scenario will be context-specific. The phases of TDR are used to help guide individuals through the process and are often not followed in this exact sequence in real life. This process is non-linear, and going back and forth between phases is common.

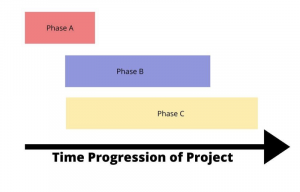

The figure below demonstrates how the phases of a transdisciplinary research approach is an iterative process. The initiation of each phase does not require the completion of the phase prior. In this example, phases B and C progress simultaneously. Additionally, as the research advances, Phase A may be revisited to introduce new participants to the research group.

Figure 1: The figure above demonstrates the progression of TDR phases in linear time, the phases occur simultaneously and overlap.

A Transdisciplinary Research Approach example and its phases are demonstrated in the box below:

Himalayan Caterpillar Fungus is a medicinal species, one of the most expensive of its kind, that is used in traditional medicine. The caterpillar fungus is in demand world-wide, it plays an economic, ecological, and cultural role. In recent years, the abundance of the Himalayan Caterpillar Fungus has declined. A transdisciplinary research approach was utilized to address the issue.

Phase A: Form a comprehensive group and define the problem

To address the decline of the Himalayan Caterpillar Fungus, a transdisciplinary research team was formed. The participants included biologists, climatologists, economists, and local harvesters. Within this research team – there were scientists, experts from economic fields, and non-academic stakeholders who held local knowledge. The participants would need to establish a common goal and create a shared language. The group defined their problem – the caterpillar fungus in the Himalayan region was declining. Possible causes for the diminishing populations include overharvesting and climate change. The local harvesters tended to believe that the root of the problem was overharvesting practices while biologists and climatologists held their viewpoint of climate change’s impact.

Phase B: Co-produce and share knowledge on solution-oriented information

Research tasks were delegated, and new knowledge was created in a collaborative manner. Local harvesters contributed site-specific environmental knowledge. Biologists contributed information on the species of Caterpillar Fungus and climatologists collected data on regional trends to apply to the decline. The new knowledge co-produced incorporated all of the participants’ varying ways of knowing and perspectives, the collected data was discussed among participants. Co-production of knowledge ensured that the research was relevant and trusted and that all involved understood the information.

Phase C: Apply co-produced knowledge to social and scientific fields

A necessary component of TDR is transferring the knowledge to action. The co-produced knowledge must be applied and implemented to scientific and social practices. The group determined that both climate change and overharvesting were contributing to the diminishing population of Caterpillar Fungus in the Himalayan region. Changes in winter temperatures and seasonal patterns could drastically reduce Caterpillar Fungus growth while a rise in temperature benefitted the population growth. The fluctuation was contributing to an unstable population, and other disturbance factors contributed to the issue. A major disturbance and predominant factor in the decline was the overharvesting. The research group determined that implementation sustainable harvest management policies was the optimal solution to maintaining the Himalayan Caterpillar Fungus population. The sustainable management policies acknowledged the role the species plays in the economic livelihood of local harvesters and the global demand, while balancing the ecological factors.

The case study above is not an exhaustive example of TDR, there are many successful and on-going projects. Later on in the SUST Methods Reader, chapter 10 will present three relevant case studies.

Benefits and Challenges of TDR

TDR is most beneficial when the problem is complex, undefined, and does not have one easy, specific solution. TDR focuses on knowledge creation, so the problem must be complex enough that we don’t have all of the information available and it must be created. The problems are often viewed differently by academic disciplines and non-academic stakeholders, which allows for multiple opinions and perspectives. These different perspectives help the project do the most good for the most amount of people because different aspects of society are represented by the different stakeholders. Stakeholders can contribute credible knowledge, critical resources, and unique insight that is effective and beyond the perspective and focus of the academic disciplines. These key stakeholders can also consider key social and political variables that further the project.

Some challenges do arise when conducting TDR. One big challenge is taking the knowledge created in the TDR process, applying it, and seeing some sort of action come out of it. This is challenging because once the research process is completed, the group has to identify specific solutions and actions based on the knowledge that was created. Oftentimes the solution to the problem isn’t explicit. Also, sometimes the stakeholders that can actually enact a solution are not included in the process, which becomes a problem when it comes time to put the knowledge created into application. If they were not involved from the beginning, they may have a harder time understanding or finding relevance in this new knowledge. Another challenge is the disparities between the experts and the key stakeholders. The non-academic stakeholders may not value their academic colleagues and their opinions, or vice-versa. Another issue with TDR is that the stakeholders and the scientific experts will often come into the project with different goals, thoughts, and ideas for the project, so this makes the planning stage of TDR difficult.

How Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Approaches Differ

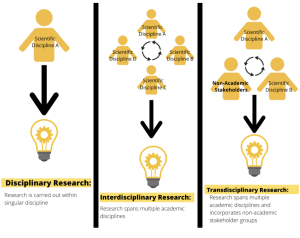

The fundamental difference between interdisciplinary research and transdisciplinary research is that interdisciplinary research does not involve non-academic stakeholders in the research process, whereas transdisciplinary research includes the participation of non-academic stakeholders in the production of knowledge and decision making. The figure below demonstrates this difference:

Figure 2: The image above provides a visual to distinguish traditional disciplinary research and inter- and transdisciplinary research approaches.

There are different uses for both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. Interdisciplinary research is excellent for answering academia-based questions, as it fosters an environment of diversity and creativity within a world that is traditionally divided by academic subjects. Interdisciplinary research does not include non-academic stakeholders and it may be difficult for individuals outside of academia to understand and interpret the knowledge produced in interdisciplinary research. Interdisciplinary research is used to produce knowledge and answer questions for more defined, less complex problems that require expertise from those with academic backgrounds. Transdisciplinary research is solution-oriented as well as context specific, and is better suited for complex problems that have yet to be defined by the group. TDR also requires knowledge and participation from non-academic stakeholders. Whether input from stakeholders is based on experimental and historical knowledge or opinions from those who will be impacted, the role of the stakeholder is as vital to the TDR process as those from academia.

There are different goals and requirements for both IDR and TDR approaches. Interdisciplinary research has the goal of advancing and creating more knowledge to solve a real-world problem through the collaboration of two or more disciplines. IDR focuses on integrating data, techniques and concepts to provide a better understanding or to create a solution to the problem. Transdisciplinary research is solution-oriented and looks to create a solution to a socially relevant problem. TDR also requires the collaboration of experts in scientific disciplines and non-academic stakeholders in order to create solution-oriented knowledge that can be applied to both scientific and societal practices.

Chapter Summary

Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research are both great methods for creating solutions to real-world sustainability problems. Both approaches promote shared learning and the creation of new knowledge from relevant disciplines. Shared learning and the creation of knowledge allows for a better understanding of the problem to make informed decisions working towards a solution. Solutions are more likely to be successful when knowledge is shared and created while working in groups of relevant participants. This is because of the shared responsibility and reduced participant work load, shared power to make decisions, and participant ability to enact solutions. It is crucial when creating a group to involve participants that have the ability to enact solutions, because a solution will not be successful if the group points responsibility to enact their solution on another person, group, or entity without having them participate in the process.

An important step that must be taken first when trying to address a sustainability problem is to identify all stakeholders that will be impacted by the solution and involving experts that provide relevant information when creating a solution. Stakeholders that will be impacted by a solution to a sustainability problem have knowledge and perspectives that are crucial to the transdisciplinary research process, but may not be necessary in all research approaches. When non-academic stakeholders are not necessary, an interdisciplinary approach involving experts of relevant disciplines will be the best method to provide answers to academic questions in hopes to find a solution. Deciding who should be involved in the project comes from the context of the problem itself and from social networks by involving those who have an interest in the problem and want to participate in the process.

While conducting interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary research, it is important to note that research approaches will be context-specific and that there is no “one size fits all” solution. The case studies presented in this chapter have been ideal uses of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research approaches and not all cases will look exactly the same.

With the rise of sustainability challenges due to climate change and other social, economic, and environmental issues, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches are desirable methods to achieve scientific knowledge while incorporating real-world perspectives. The collaboration of two or more relevant disciplines allows for successful outcomes when addressing sustainability problems. Since sustainability issues tend to involve a range of stakeholders and factors that impact social, economic and environmental issues, it is important to include experts and non-academic stakeholders when the situation calls for it.

Comprehension Questions

- What types of problems are best solved using transdisciplinary research?

- What are the differences between interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research?

- True or false: The phases of TDR have a strict and linear order; you must complete one to move onto the next.

- What is a benefit of having non-academic stakeholders involved in the research process?

a field of study or branch of knowledge

a research method in which both experts and non-experts work together to co-produce knowledge in order to create solutions to solve complex problems