7

The most recent updated version of this chapter is at: https://opentext.ku.edu/teams/chapter/teams-as-systems/

Content in this chapter comes from the Open University at Open.edu. Source 1 and Source 2

Creating successful teams: A holistic view

This section focusses on an open systems’ approach to teamwork – a helpful approach which encourages teams to consider the context in which they works. The approach considers team processes, which are divided into three parts: inputs, throughputs and outputs. These highlight the different issues and activities a team and leaders needs to engage with or oversee during the life of a team. As you read, think about the processes the team went through (or will go through).

Inputs, throughputs and outputs

The systems perspective ask us to think of teams as part of the wider context of an organization or the community. Considering a systems perspective ensures that team-leaders can find the resources to help the team function successfully. A systems perspective asks: what needs to be controlled, monitored and/ or influenced within and outside the team? At the same time, leaders needs to consider the team in terms of its task phases and processes, from start to finish. This allows leaders put a particular team-related issue in context in order to understand it better.

A leader’s task is to understand, plan and monitor all these different processes. This seemingly complex and unwieldy task is easier to understand and manage when broken down into its component parts. The open systems model of team work (Schermerhorn et al., 1995; Ingram et al., 1997) can help to explain and characterize effective team-work processes.

The open systems approach to team working

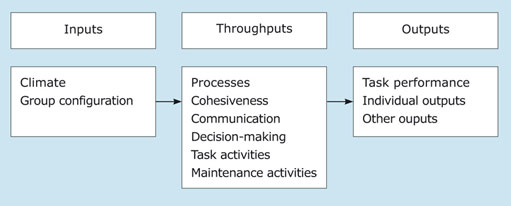

Schermerhorn and colleagues suggest that teamwork can be considered as a three-stage sequence. Teams are viewed as systems which take in resources such as time, people, skills, problems (inputs) and through transformational processes (throughputs) such as decision-making and different behaviors and activities, transform them into outputs, such as work, solutions and satisfactions (Ingram et al., 1997). Thus, team performance is the collective competencies, knowledge, and actions of team members (DiSanza & Legge, 2017). This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Inputs are factors which are controlled and influenced by management. They include ‘climate’, the atmosphere under which the team works, and ‘group configuration’, how the team is put together, who is selected to work in it and why. Management will also influence how a team should work by making sure at the outset that the team strategy is in line with the vision and strategic direction of the organization and that it uses the organization’s preferred work practices; for example, face-to-face or virtual working.

Throughputs refer to the activities and tasks that help to transform inputs into outputs. They may have the greatest influence on effective team work as they include team processes such as developing and maintaining cohesiveness, and communication. They also involve task activities which get the work done and maintenance activities which support the development and smooth functioning of the team.

Outputs are those (successful) outcomes which satisfy organizational or personal goals or other predetermined criteria. The success of outputs may be assessed by a number of stakeholders, including the organization itself and team members, and by a range of other stakeholders. Team outputs include the performance of team tasks and individual outputs (such as professional development).

How can this framework be applied in a way which highlights how to manage or lead a team and its task? Imagine you have been asked to put together a team to produce the company’s internal newsletter. What inputs, throughputs and outputs would you need? What questions would you need to ask yourself about different aspects of the process? We now consider what you might need to think about for the newsletter example. Some of the questions could be adapted and applied to other situations as well.

Inputs

Inputs are often controlled or influenced by management. This may be the direct manager of the group or team or the result of senior management decisions and strategies. This means in practice that the way a team is put together and will function is influenced by the organization’s values, vision and strategy, and its practices and procedures.

Two main factors to consider at this stage are communication climate and group configuration. Communication climate refers to the communicative norms for a workplace, usually this focuses on how willing or unwilling people are to raise issues or concerns and to speak freely. Group configuration refers to the roles adopted by group members. Some groups have strong hierarchy (the leader makes all decisions) other groups distribute decisions among all members (i.e., democratic or egalitarian). The communication climate and configuration of members determines how inputs can be leveraged.

Some input-related questions for you to consider at this stage are given in Table 1:

Table 1 Input-related questions

How much support is there for this newsletter among senior management?

Who might need to be influenced?

What objectives will it fulfill?

What resources will be provided for it? What others might be needed? Where could they come from?

How will individuals working on this be rewarded or recognized?

What might they learn? What skills could they hope to develop?

How many people will be needed to perform this task?

What technical skills are needed (e.g. desktop publishing)?

What training and development opportunities are available?

What roles are needed (e.g. a co-coordinator)?

Who might work well together?

Throughputs

Some common throughputs include:

Team processes. A sense of unity is created through sharing clear goals which are understood and accepted by the members.

Cohesiveness. This involves encouraging feelings of belonging, cooperation, openness and commitment to the team.

Communication. This involves being clear, accurate, open and honest.

Decision-making. This involves making sure that established procedures are in place, that everybody is clear about leadership and an environment of trust is being created.

Task and maintenance activities. These include activities that ensure that the task is produced effectively, such as planning, agreeing on procedures and controls. They also include activities that minimise threats to the process, such as monitoring and reviewing internal processes and dealing constructively with conflict.

In Table 2, you’ll find out more on “Throughputs”:

Table 2: Throughputs

Some common throughputs include:

Team processes. A sense of unity is created through sharing clear goals which are understood and accepted by the members.

Cohesiveness. This involves encouraging feelings of belonging, cooperation, openness and commitment to the team.

Communication. This involves being clear, accurate, open and honest.

Decision-making. This involves making sure that established procedures are in place, that everybody is clear about leadership and an environment of trust is being created.

Task and maintenance activities. These include activities that ensure that the task is produced effectively, such as planning, agreeing on procedures and controls. They also include activities that minimize threats to the process, such as monitoring and reviewing internal processes and dealing constructively with conflict.

In the case of the newsletter project, you may need to think about ways of setting up the project. Would it be possible to have a team away day? If so, what would the themes of the day be? Perhaps you could work backwards from the finished product. How do team members envisage the newsletter in terms of aim, goals, content and look? Can they come up with an appropriate design and name for the newsletter? Then, what needs to be done in order for this to be produced? Some ground rules for working together may also need to be set at an early stage. Some throughput-related questions are set out in Table 3.

Table 3: Throughput-related questions

What can you do to build a sense of belonging among the team members?

How will the group communicate? (Face-to-face, email, group software?)

Do any ground rules need setting up? How can this be done?

What established procedures for decision-making are there?

Will there be a team leader? How will the person be chosen?

What tasks need to be performed to complete the project?

What maintenance behaviors does the group need to exhibit to get the job done and to benefit and develop from the experience?

Who will be responsible for ensuring that the different tasks and maintenance activities are performed?

Are there structures and systems in place to review processes?

Outputs

Outcomes can be examined in terms of task performance, individual performance and other (incidental) outcomes.

Task performance. This may be judged on a number of criteria, such as quality of the formal outputs or objectives. In this case a product (the newsletter) and the time taken to perform the task are the criteria.

Individual outputs. These may include personal satisfaction and personal development and learning.

Other outcomes. These include transferable skills to apply in future to other teamwork. They include, for example, experience of effective teamwork and task-specific skills.

In general, it is always appropriate to evaluate outcomes. In this case you may need to think about:

- Evaluating the newsletter itself. Was it well-received?

- Evaluating individual outcomes. Have members developed transferable skills that they can take to new projects?

- Evaluating other outcomes. Has the experience enhanced team members’ ability to work in a team?

Some output-related questions are set out in Table 4.

Table 4 Output-related questions

Has the team completed the task it was given?

Has it kept to cost and to time?

What has the team learned from this experience?

Should the team now be broken up or could it go on to another activity?

What have individuals learned from the experience?

Have members experienced an effective team?

Have any learning and development needs been identified? How can they be addressed?

Have members developed transferable teamworking and other skills?

Where can these skills be used in the organization?

The open systems model of teamwork shows us how effective teamwork can offer benefits to organization and staff. However, it also shows us that these benefits do not occur without effort and planning. Leaders need to ensure that the right team is put together to perform a given task and that it is given appropriate tasks. They also need to secure the freedom, resources and support for the team to undertake the task. The model alerts teams and leaders to both the micro and the macro issues they will need to be aware of in managing effective teams.

Group size

Another significant feature of a work group is its size. To be effective it should be neither too large nor too small. As membership increases there is a trade-off between increased collective expertise and decreased involvement and satisfaction of individual members. A very small group may not have the range of skills it requires to function well. The optimum size depends partly on the group’s purpose. A group for information sharing or decision making may need to be larger than one for problem solving.

A simple calculation can indicate how quickly the number of two-way interactions in a group increases with increasing size. In a group of N people (where N stands for a number) each of the N individuals relates with N × 1 others, so there are N × (N − 1) / 2 possible interactions.

In many organizations, there is a tendency to include representatives from every conceivable grouping on all committees in the belief that this enhances participation and effectiveness. There is also the view that putting a representative of every possible related department into a given group helps smooth information flow and project progress. In practice, communication is usually reduced in larger groups. As the group size grows, members feel less involved in the process, alienation tends to increase and commitment to the project tends to decrease. The numbers most commonly quoted for effective group size in a face-to-face team are between 5 and 10, so reducing the number of interactions and lessening the risk of conflict.

There is a nice demonstration that the ‘between 5 and 10’ rule is due to communication limitations. If we devise special procedures to manage the interpersonal exchanges (as in some computer-based brainstorming systems, where the computers handle all the gathering and feeding back of ideas) the advantages of the small group disappears: the larger the group, the more ideas are generated.

However, in the normal face-to-face mode, if there are more than about 12 members in our team we are likely to encounter group-size problems. If the numbers cannot be reduced we might consider restructuring the team into sub-groups and delegating responsibility for achieving some of the team’s objectives. We may find that if we don’t do this deliberately it will happen anyway. For instance, members who like each other or share common interests may spontaneously form sub-groups.

Unfortunately, the breakdown of large groups into sub-groups and cliques may not help a team achieve its goals. One device for keeping large numbers of people informed about a project is for a small group to manage the task and for it to invite relevant people to attend particular meetings. Alternatively, the small group can arrange to give information seminars to larger groups of colleagues. So, for the purposes of achieving team goals it is better that the process of restructuring big groups into smaller groups is managed consciously and carefully.

Managing group membership

The range of people that makes up the membership of a team, and the relationships they have with each other, have great influence on the team’s effectiveness. The members should all be able to contribute their skills and expertise to the team’s goals to make the best use of the resources. If you are ever in the position of being able to select your own team, you will need to identify your objectives and the methods for achieving your goals. From this will come the competences – the knowledge, understanding, skills and personal qualities – which you need in your team members.

The least-sized group principle contends that the ideal group size is one which incorporates a wide variety of views and opinions but contains as few members as possible. Restated, a group should be as small as possible while still incorporating as wide a range of perspectives as possible. It is important to appraise as systematically as possible the relationship between team functions and required competences in order to identify gaps and begin to allocate responsibilities, organize training and so on. Figure 2 provides a useful way of weighing up the mixture of ‘task’ and ‘people’ functions (or ‘faces’) of a team.

Overview

Faces 1 and 2 are external to the team and concern:

- adapting to the environment and using organizational resources effectively in order to satisfy the requirements of the team’s sponsor.

- relating effectively with people outside the team in order to meet the needs of clients or customers, whether internal or external to the organization.

Faces 3 and 4 are internal to the team and concern:

- using systems and procedures appropriately to carry out goal-oriented tasks.

- working in a way which makes people feel part of a team.

Each face implies different competences.

We may find that when we are setting up a team we have to guess a little about the competences that are required. We may also find that as the team develops and gets on with its work, there are changes in everyone’s perception of the skills and knowledge needed. It is therefore important to keep an eye on changes that affect the expertise needed by the team and actively recruit new members if necessary. It is frequently the case that team members have other work commitments outside the team. The implications of this should be taken into account when recruiting team members and allocating tasks and responsibilities to them. Team loyalties and commitments need to be balanced with other loyalties and commitments. Often we will have limited or no choice about who is recruited to the team. We may find that we just have to make do with the situation and struggle to be effective despite limitations in the competence base.

As well as competencies there are other factors that can influence the working of a team. The balance of men and women and people from different nationalities or cultural backgrounds all play a part. Differences in personality can also have a significant effect. Achieving the best mix in a team invariably involves working on the tensions that surround issues of uniformity and diversity. The pushes and pulls in different directions need to be managed. The dismantling of many of the restrictions in the European labour market supports moves towards recruitment practices which seek team members with proven capabilities to work in other countries. Legislation and social changes make it easier for organizations to develop and train their staff to appreciate ethnic and national differences in values, style, attitudes and performance standards. Nevertheless, there are countervailing tendencies, internally and externally.

Developing openness and trust, for example, can often seem easier in the first instance on the basis of a high degree of homogeneity; strengthening diversity can seem threatening in an established team.

Functional and team roles

When individuals are being selected for membership of a team, the choice is usually made on the basis of task-related issues, such as their prior skills, knowledge, and experience. However, team effectiveness is equally dependent on the personal qualities and attributes of individual team members. It is just as important to select for these as well.

When we work with other people in a group or team we each bring two types of role to that relationship. The first, and more obvious, is our functional role, which relies on the skills and experiences that we bring to the project or problem in hand. The second, and often overlooked, contribution is our team role, which tends to be based on our personality or preferred style of action. To a large extent, our team role can be said to determine how we apply the skills and experiences that comprise our functional role.

Belbin (1981, 1993) researched the functional role/team role distinction and its implications for teams. He found that, while there are a few people who do not function well in any team role, most of us have perhaps two or three roles that we feel comfortable in (our so-called ‘preferred roles’) and others in which we feel less at ease (our so-called ‘non-preferred roles’). In fact, Belbin and his associates identified nine such team roles. Some of the non-preferred roles are ones we can cope with if we have to. However, there are also likely to be others in which we are both uncomfortable and ineffective.

Belbin’s nine team roles are listed in Table 1. It is worth noting that all nine are equally important to team effectiveness, provided that they are used by the team at the right times and in an appropriate manner.

When a team first addresses a problem or kicks off a project, the basic requirement is usually for innovative ideas (the need for a ‘plant’), closely followed by the requirement to appreciate how these ideas can be turned into practical actions and manageable tasks (the ‘implementer’). These steps stand most chance of being achieved if the team has a good chairperson (the ‘coordinator’) who ensures that the appropriate team members contribute at the right times. Drive and impetus are brought to the team’s activities by the energetic ‘shaper’. When delicate negotiations with contacts outside the team are called for, it is the personality of the ‘resource investigator’ that comes into its own. To stop the team becoming over-enthusiastic and missing key points, the ‘monitor/evaluator’ must be allowed to play a part. Any sources of friction or misunderstanding within the team are diffused by the ‘teamworker’, whilst the ‘specialist’ is used for skills or knowledge that are in short supply and not used regularly. The ‘completer/finisher’ ensures that proper attention is paid to the details of any solutions or follow-up actions.

It is essential that team members share details of their team roles with their colleagues if the team is to gain the full benefit from its range of roles; the team can then see if any of the nine team roles are missing. If this is the case, those team members whose non-preferred roles match the missing roles need to make the effort required to fill the gap. If not it may be necessary to bring in additional team members. Clearly, this sharing calls for a degree of openness and trust, which should exist in a well-organised, well-led team. Unfortunately, in teams that have not yet developed mutual trust and openness, some people who may be quite open about the details of their functional roles tend to be somewhat coy about sharing personality details. A competent leader will handle this situation in a sensitive manner.

Table 1:

Belbin team roles

| Team role | Team strengths | Allowable weaknesses |

| Plant | Creative, imaginative, unorthodox | Weak in communication skills |

| An innovator | Easily upset | |

| Team’s source of original ideas | Can dwell on ‘interesting ideas’ | |

| Implementer | Turns ideas into practical actions | Somewhat inflexible |

| Turns decisions into manageable tasks | Does not like ‘airy-fairy’ ideas | |

| Brings method to the team’s activities | Upset by frequent changes of plan | |

| Completer-finisher | Painstaking and conscientious | Anxious introvert; inclined to worry |

| Sees tasks through to completion | Reluctant to delegate | |

| Delivers on time | Dislikes casual approach by others | |

| Monitor-evaluator | Offers dispassionate, critical analysis | Lacks drive and inspiration |

| Has a strategic, discerning view | Lacks warmth and imagination | |

| Judges accurately; sees all options | Can lower morale by being a damper | |

| Resource investigator | Diplomat with many contacts | Loses interest as enthusiasm wanes |

| Improviser; explores opportunities | Jumps from one task to another | |

| Enthusiastic and communicative | Thrives on pressure | |

| Shaper | Task minded; brings drive to the team | Easily provoked or frustrated |

| Makes things happen | Impulsive and impatient | |

| Dynamic, outgoing and challenging | Intolerant of woolliness or vagueness | |

| Teamworker | Promotes team harmony; diffuses friction | Indecisive in crunch situations |

| Listens; builds on the ideas of others | May avoid confrontation situations | |

| Sensitive but gently assertive | May avoid commitment at decision time | |

| Coordinator | Clarifies goals; good chairperson | Can be seen as manipulative |

| Promotes decision making | Inclined to let others do the work | |

| Good communicator; social leader | May take credit for the team’s work | |

| Specialist | Provides rare skills and knowledge | Contributes only on a narrow front |

| Single-minded and focused | Communication skills are often weak | |

| Self-starting and dedicated | Often cannot see the ‘big picture’ |

Leaders sometimes try to rationalize having teams that are unbalanced in a team-role sense by claiming that they have been assigned a group of people as their team and they must live with it. In most of today’s workplaces there is a steady and regular movement of staff in and out of management groups and departments. When selecting or accepting new people into their groups or departments, leaders with an understanding of team-role concepts will look for team-role strengths in addition to functional-role strengths.

Each team role brings valuable strengths to the overall team (team strength), but each also has a downside. Belbin has coined the phrase ‘an allowable weakness’ for what is the converse of a team strength. The tendency is for a leader to try to correct perceived weaknesses in an employee. But by doing this with allowable weaknesses we face the possibility of not only failing to eradicate what is after all a natural weakness, but also risking undermining the strength that goes with it. This is not to suggest that weaknesses should not be addressed. The point is that any attempts at improvement should be kept in balance and we should be prepared to manage and work around the weaknesses of our team colleagues and ourselves. Many people put on an act in an attempt to hide their weaknesses. Once they see that they can admit to them without prejudice, they feel a sense of relief and are ready to play their part in the team in a more open manner.