Casey Dorrell

casey.dorrell@ontariotechu.net

Ontario Tech University

Abstract

Online asynchronous learning has long been presented as an obstacle to overcome in instructional design, especially when considered through the framework of social constructivism (Freeman, 2010). Social constructivism not only values the social aspect of learning but deems it a requisite part of any learning, whereas asynchronous learning is typically seen as fundamentally solitary. A clear divide exists. This chapter presents a different viewpoint by exploring opportunities to engage in social learning within asynchronous instruction. Most of this chapter is focused on establishing a clear understanding of social constructivism and delineating it from other similar concepts, beginning by explaining social constructivism, clarifying the different types of constructivism, then delving into the related concept of the Zone of Proximal Development and its implications for the concept of scaffolding. Once the framework is fully established, two opportunities for integrating social constructivism are explained along with some examples of technologies that can be used toward that end.

Keywords

asynchronous, constructivism, online learning, social constructivism, Vygotsky

Introduction

Social constructivism’s broad adoption is a relatively recent development in education at all levels, representing a clear shift away from historical understandings of learning, requiring a reconceptualization of the role of the instructor and the learner (Brown, 2006). This shift in how we conceive of learning has taken place alongside a concurrent shift in the mediated environment of learning, most evident in so-called “distance learning” — more precisely referred to as “online learning” as the benefits of learning online no longer require physical distance as an assumed precondition of application.

In more straightforward terms, the way we think of learning has changed, and so have the environments in which learning happens. This short chapter looks specifically at what social constructivism is, how it can benefit learners, and ultimately how learning in an asynchronous online environment can help facilitate learning through a social constructivist lens.

Background Information

Despite the widespread adoption of social constructivism across all levels of education, there is a surprising lack of consistency and agreement on terminology between practitioners with cognitivism, social learning theory, social constructivism, and constructivism often used interchangeably, or the distinctions between the different terms shifting from one writer to the next. Geelan (1997) described the situation as “epistemological anarchy” and there is no sign that the twenty years since that declaration have brought any clarity to the field (p. 26).

Social Constructivism: Defining a Term

When authors refer to constructivism as a general term, they are more often talking about social constructivism, a term that originates with a pre-Soviet Russian psychologist, Lev Vygotsky, whose social theory of development and learning came to prominence thirty years after his death in the 1960s (Yarbrough, 2008). Aside from social constructivism, the next most prominent version of constructivism is cognitive constructivism which roughly aligns with the theories of Jean Piaget. A more helpful nomenclature has been suggested by Geelan (1997) as personal constructivism (Piaget) and contextual constructivism (Piaget).

Both theories are built on the idea that knowledge is constructed rather than found or transmitted, and that this is an active rather than a passive process. Social constructivism emphasizes the social nature of this act of creation, with an understanding that knowledge is created when an individual expresses idea through language. This means that language, expression, and therefore social engagement are necessary for real learning (Yarbrough, 2008). Cognitive constructivism is the idea that knowledge is constructed internally, within an individual’s mind, and that this process in an individual is a subjective one of assimilating knowledge and adapting it into prior constructs and knowledge (Geelan 1997). Both versions of constructivism are often presented in reductionist terms as binaries, but social constructivists do believe that internal thoughts and solitary work are a part of learning, just as cognitive constructivists value social learning, especially between peers (Hassad, 2011).

While Piaget and Vygotsky both account for the environment and social influences to varying degrees, a clear way of distinguishing between their versions of constructivism is an order of operations — that is whether the knowledge is first constructed within an individual and then expressed socially, or whether the construction itself is a social act which only after expression can be internalized (Liu & Matthews, 2005). Vygotsky and more recent researchers working in his theoretical wake argue that knowledge is inherently social, that language is the vessel of knowledge construction, and that language itself is context and socially dependent (Geelan, 1997; Liu & Matthews, 2005). The practical outcome of this view for teaching is a de-emphasis of the authority of the instructor and an emphasis on relationships, as well as on a variety and diversity of student voices. Other variants of social constructivism differ on the degree to which they emphasize language and whether they make special account of the role of a learner’s culture as part of the integration of new knowledge into pre-existing constructs (Geelan, 1997).

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

Although the constructivist theories of both Vygotsky and Piaget get deep into the role of language and cognitive functions, the most salient elements to consider for practical application in an online environment are the linked concepts of a More Knowledgeable Other (MKO) and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

An MKO is any person that can help an individual learn. Originally conceived more narrowly as a person that could help a child learn a skill, possibly a peer but likely a teacher, Piaget expanded that view to anyone and emphasized the peer-element over teacher intervention, stating that there are two classrooms: one which includes the instructor and one which does not (Russell, 2006). The idea of an MKO has now been expanded to account for all types of learning, not just skill-acquisition. More relevant to online applications explored in this paper, the concept of MKO has also been extended beyond humans to account for learning from adaptive computer programs and Artificial Intelligence (Cicconi, 2014).

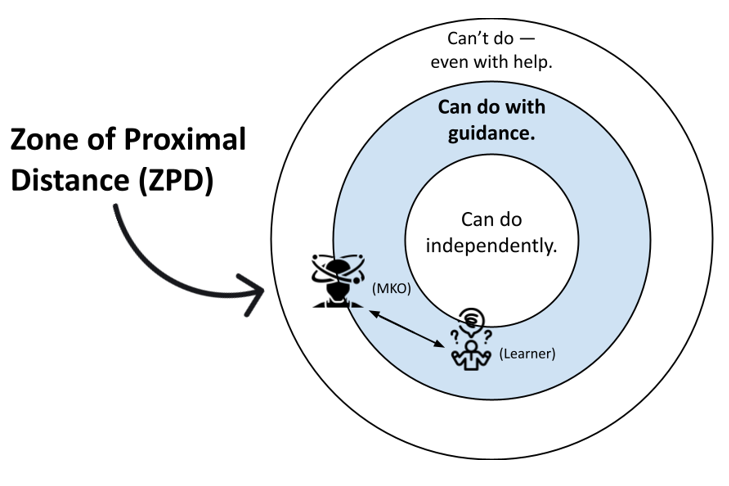

The concept of an MKO can be understood in conjunction with the idea of ZPD, as shown in Figure 1, which essentially imagines a zone within which a learner can comfortably learn and understand concepts. Surrounding that zone is a secondary zone of things a learner can learn with guidance, from an MKO. The third zone surrounding these two represents learning currently out of reach for the learner. As the learner gains more knowledge, the zones would expand (Hall, 2007). The implications of this idea are that to effectively guide a learner, one must be able to define their current zone of prior knowledge and accurately assess their zone of potential knowledge, and that this evaluative process would be ongoing as a learner’s zones continue to expand and change over time.

Figure 1

The Zone of Proximal Development

Note: This diagram is based on the writing of Hall (2007) explaining the theories of Vygotsky.

These implications bring us to the concept of scaffolding. Scaffolding, while directly linked to the idea of ZPD, actually comes from Jerome Bruner who continued Vygotsky’s work and used the idea of scaffolding to actively get a student who is not yet equipped to learn a subject to the place where they are ready (Stapleton & Stefaniak, 2019). Bruner modeled the idea of scaffolding on parental instruction to come up with five key features of scaffolding: reducing complexity, getting and keeping a learner’s focus, offering models, building on something immediate, and providing support (De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000).

In other words, scaffolding should help keep a learner on task and motivate them by being at the appropriate level of difficulty giving the learner both a sense of adequate challenge and satisfaction of accomplishment to propel them forward (De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000; Stapleton & Stefaniak, 2019). A specific type of scaffolding called “spiral curriculum” that Bruner recommended was to introduce complex ideas early, even when they are beyond the comprehension of the learner, then slowly build up the elements of those ideas through the curriculum, repeatedly alternating between the basic and the complex until the learner grasps it all. The key to an effective spiral curriculum is active engagement – instructional strategies that create a sense of discovery and creativity (Stapleton & Stefaniak, 2019).

Asynchronous Learning

Recent advances in online connectivity along with advances in online applications to facilitate learning like Zoom (Zoom, 2022) or Adobe Connect (Adobe, 2022) have rendered the distinction between in-person learning and online synchronous learning increasingly meaningless. Yet, asynchronous online learning is still very common, especially at the post-secondary level, where it provides reach and cost-effectiveness for institutions and flexibility for learners (Jorgensen, 2003). When operating within the social constructivist framework, though, it is unclear whether asynchronous instruction limits real learning.

This idea was most famously explored by Moore (1989) writing about the precursor to online asynchronous instruction, the correspondence course, where he identified the obstacle to asynchronous learning as the psychological perception of distance between both a learner and their instructor and between the learners themselves. A sort of inverse relationship between that psychological distance and the number and variety of opportunities for interactions was conceived by Moore, meaning that more interactions of more types would decrease perceived distance (Moore, 1989).

Applications

Applying social constructivism to asynchronous learning and overcoming the inherent pitfalls therein is not something that can be solved by an individual technology, platform, or application. Instead, a more helpful way of approaching the issue is by identifying opportunities for social constructivist technology in general. That is to say, much of the literature focuses on identifying issues with asynchronous learning and then looking for solutions to those problems (Laffey et al., 2006), or offering overly simplistic solutions, summed up nicely by Weller (2020) as the “we gave them a forum” solution to teaching wherein an instructor gives students a forum and calling it a day, undervaluing the role of instructional design and guidance (p. 30).

A better approach may be to identify the ways in which asynchronous learning has a social constructivist advantage over traditional and synchronous learning. Two such opportunities, flexible peer interactions and Dynamic Assessment, are outlined below, expressed as principles of social constructivism.

Flexible Peer Interactions

Peer-mediated scaffolding, scaffolding material through some type of peer engagement, is a key element of social constructivist curricular design, but it needs to be flexible (De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000). For example, in language acquisition, a common practice is absolute immersion where the learners only converse in the new language (Christoffersen, 2017) but mandating this can actually be counterproductive. Allowing peer-to-peer engagement that is less structured can stimulate discussion, increase positive feelings of social interaction, and allow learners to establish their prior knowledge as a group, and stimulate reflection (De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000).

This is something that asynchronous curricular design can more easily achieve with an already built-in reduced teacher-presence, creating the opportunity for less structured peer-to-peer environments. It can be done with any technology that is informal and does not include the direct or indirect oversight of an instructor, allowing for less structured socialization (Russell, 2006) such as WhatsApp, Signal, or Google Chat (Google, 2022; Signal Messenger, 2022; WhatsApp, 2022). A Learning Management System forum, on the other hand, may create a more structured environment with implied instructor oversight, making it less useful toward the goal of flexible peer interactions.

Allowing for multiple means of unsurveilled peer-to-peer discourse can also help to minimize the power imbalances that inevitably arise when discussion is mandated and graded by an instructor (Gulati, 2008). For many learners, a sense of privacy and feeling of safety is a precondition of being able to participate socially and engage in social constructivist learning (Gulati, 2008). Different applications provide different strengths in this regard, but all have the intrinsic advantage over in-person groups. For example, many institutions already have Google Apps integrated into their institutional ecosystem, meaning there will be less of a barrier to tech adoption (Sabah, 2016) to use the system for group work. But that comes at a cost of perceived privacy given concerns about Google generally (Brown, 2016). Signal, on the other hand, has a larger barrier to entry but is known for privacy (Signal Messenger, 2022).

Ultimately, the need for flexibility means that the best approach is to provide options and support to students but not to mandate a specific platform.

Dynamic Assessment

A clear implication of ZPD and scaffolding is that an instructor needs to be able to accurately assess the current level of understanding and knowledge of a learner in order to help expand that knowledge or create the environment for that expansion. For this reason, Vygotsky is often referred to as the pioneer of Dynamic Assessment (DA) (Daneshfar & Moharami, 2018). DA, like it the name implies, means assessments where the learner’s level of understanding is being assessed live and the questions are adaptive based on the learner’s responses with the goal being to both assess current learning and to support and expand that learning, meaning that the DA itself becomes and MKO.

Again, asynchronous learning renders DA easier than in-person instruction, through the use of computerized DA allowing a dynamic, fluid assessment without any live instructor interventions, meaning that any number of learners could participate in a DA simultaneously (Poehner & Lantolf, 2013). DA is the opposite of “teaching to the test” wherein the test is treated as a fluid part of the learning process rather than a static method of determining achieved learning (Poehner & Lantolf, 2013). Essentially, testing is seen as a type of formative evaluation with DA rather than a summative one.

Two excellent platforms of integrating DA into online learning are the Articulate Storyline system (Articulate Global, 2022) for advanced systems or simply using the Learning Management System (LMS) that a course is already housed on. All modern LMSs offer some form of dynamic testing where the questions asked, and question-order can be predicated on the answers given by students and where specific feedback can be given live to students based on their answers. This can be an iterative process as well, where the results of one cohort can be used to further adapt future implementation.

Conclusion and Future Recommendations

Asynchronous instruction, especially at the post-secondary level, is here to stay. There are too many perceived benefits to both learners and institutions. But that does not need to be conceived as a limitation or problem to overcome. Instead, a reconceptualization of asynchronous learning within a social constructivist framework demands that instructional designers look to the opportunities that asynchronous structures offer that are not present in synchronous learning. Two such opportunities, DA and flexible peer interactions were explored here, but there are certainly many more to discover. Areas for future research include testing different platforms for both opportunities explored in this paper and exploring other potential social advantages of asynchronous learning.

References

Adobe (2022). Adobe Connect (Version 11.4.5) [Computer Software]. https://www.adobe.com/ca/products/adobeconnect.html

Articulate Global LLC. (2022). Articulate Storyline 3 (Version 3.17.27621.0) [Computer Software]. https://articulate.com/360/storyline

Brown, E. (2016, February 16). Google says it tracks personal student data, but not for advertising. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2016/02/16/google-says-it-tracks-personal-student-data-but-not-for-advertising/

Brown, T. H. (2006). Beyond constructivism: Navigationism in the knowledge era. On the Horizon, 14(3), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120610690681

Christoffersen, K. O. (2017). What Students Do with Words: Language Use and Communicative Function in Full and Partial Immersion Classrooms. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 8(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/26390043.2017.12067798

Cicconi, M. (2014). Vygotsky meets technology: A reinvention of collaboration in the early childhood mathematics classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-013-0582-9

Daneshfar, D., & Moharami, M. (2018). Dynamic Assessment in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory: Origins and main concepts. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 9, 600-607. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0903.20

De Guerrero, M. C. M., & Villamil, O. S. (2000). Activating the ZPD: Mutual scaffolding in L2 peer revision. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00052

Freeman, M. (2010). Vygotsky and the virtual classroom: Sociocultural theory comes to the communications classroom. Christian Perspectives in Education 4(1), 17.

Google (2022). Google Chat (Version 1.0.160) [Mobile App]. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/google-chat/id1163852619

Gulati, S. (2008). Compulsory participation in online discussions: Is this constructivism or normalisation of learning? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290801950427

Hall, A. (2007). Vygotsky goes online: Learning design from a socio-cultural perspective. Cultural Theory, 15.

Hassad, R. (2011). Constructivist and behaviorist approaches: Development and initial evaluation of a teaching practice Scale for introductory statistics at the college level. Numeracy, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.5038/1936-4660.4.2.7

Jorgensen, D. (2003). The challenges and benefits of asynchronous learning networks. The Reference Librarian, 37(77), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J120v37n77_02

Laffey, J., Lin, G. Y., & Lin, Y. (2006). Assessing social ability in online learning environments. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 17(2), 163–177. https://www.proquest.com/docview/211250965/abstract/7A4675BA9D94898PQ/1

Liu, C. H., & Matthews, R. (2005). Vygotsky’s philosophy: Constructivism and its criticisms examined. International Education Journal 6(3), 386-399.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2013). Bringing the ZPD into the equation: Capturing L2 development during Computerized Dynamic Assessment (C-DA). Language Teaching Research, 17(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168813482935

Russell, W. (2006). Piaget’s other classroom. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, 5(4), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.11120/ital.2006.05040064

Sabah, N. M. (2016). Exploring students’ awareness and perceptions: Influencing factors and individual differences driving m-learning adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.009

Signal Messenger LLC. (2022). Signal (Version 5.46.0) [Computer Software]. https://signal.org/download/

Stapleton, L., & Stefaniak, J. (2019). Cognitive constructivism: Revisiting Jerome Bruner’s influence on instructional design practices. TechTrends, 63(1), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0356-8

WhatsApp LLC. (2022). Whatsapp (Version 2.22.13.75) [Mobile App]. https://www.whatsapp.com/android

Yarbrough, J. R. (2008). Adapting adult learning theory to support innovative, advanced, online learning—WVMD Model. Research in Higher Education Journal 35(15).

Zoom Video Communications, Inc. (2022). ZOOM cloud meetings (Version 5.11.0) [Computer software]. https://zoom.us