VII. Popular Music

Modal Schemas

Megan Lavengood

Key Takeaways

- Many pop songs use harmonic progressions that imply modes other than major/minor.

- A modal schema may be used without the entire song being strictly within that mode.

- Modes may be compared to major and natural minor to understand what characterizes their sound (their color notes)

- Mixolydian schemas:

- Double plagal ♭VII–IV–I

- Subtonic shuttle I–♭VII

- Aeolian schemas:

- Subtonic shuttle i–♭VII (same as mixolydian, but with a minor tonic)

- Aeolian shuttle i–♭VII–♭VI–♭VII

- Aeolian cadence ♭VI–♭VII–i (or I)

- Lament i–♭VII–♭VI–v

- Dorian schemas:

- Dorian shuttle i–IV

- Lydian schemas:

- Lydian shuttle I–II♯

- Lydian cadence II♯–IV–I

This book covers modes from many different angles. For more information on modes, check Introduction to Diatonic Modes (general), Chord-Scale Theory (jazz), Diatonic Modes (20th/21st-c.), and Analyzing with Modes, Scales, and Collections (20th-/21st-c.).

“Mode” is a really complicated term. The article on mode in Grove Music Online (Powers et al. 2001), which is the standard academic encyclopedia for musicology, is 238 pages long and has nine authors. This means that, even if you think you already know about modes, you may want to set that knowledge aside before learning how modes are used in pop music.

This chapter discusses modes as they appear in certain schematic chord progressions in pop and rock music. Most of this information is based on the work of Nicole Biamonte (2010) and Philip Tagg (2011). After showing the function of modal harmonies as they compare to diatonic harmonies, common modal schemas will be introduced, grouped by the mode they borrow from.

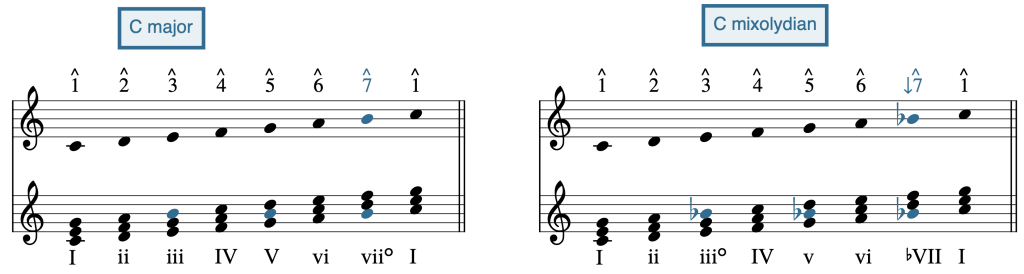

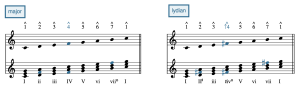

Grouping modes by whether the tonic is major or minor helps with aural identification of modal passages. This grouping is represented in Example 1. The top line shows modes whose ![]() is a major third above tonic (mi): major, mixolydian, and lydian. The bottom line shows modes whose

is a major third above tonic (mi): major, mixolydian, and lydian. The bottom line shows modes whose ![]() is a minor third above tonic (me): aeolian, dorian, and phrygian. Example 1 also illustrates what differentiates certain modes from major or minor. Each mode has exactly one pitch shown in a lighter color; this pitch is inflected when compared to major/minor. These special pitches are referred to as the color note of each mode.[1] These relationships are shown with the dotted slurs.

is a minor third above tonic (me): aeolian, dorian, and phrygian. Example 1 also illustrates what differentiates certain modes from major or minor. Each mode has exactly one pitch shown in a lighter color; this pitch is inflected when compared to major/minor. These special pitches are referred to as the color note of each mode.[1] These relationships are shown with the dotted slurs.

Example 1. Modes grouped by major vs. minor tonic, with dotted slurs connecting the distinctive color pitch of each mode with its major/minor counterpart.

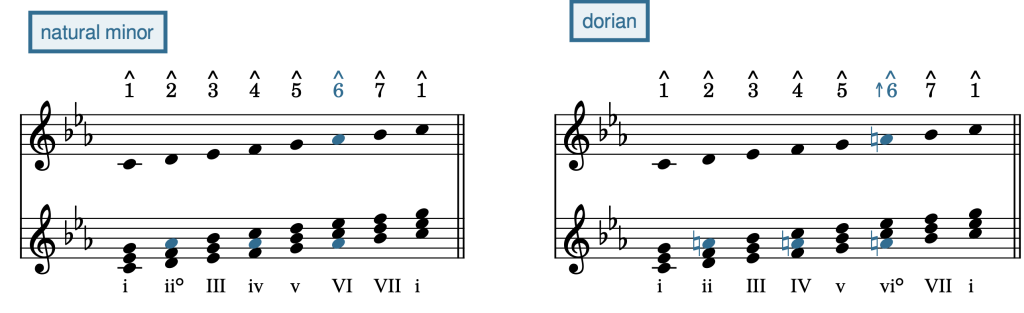

Function of Modal Harmonies

You may already have learned about tonic, subdominant, and dominant function in diatonic harmony. Modal harmonies basically align in function with their diatonic counterparts, although the additional modal inflections create greater overlap between these functions. This is summarized in Example 2.

This illustration of harmonic function may help you to understand why certain modal progressions seem as goal-oriented as diatonic progressions.

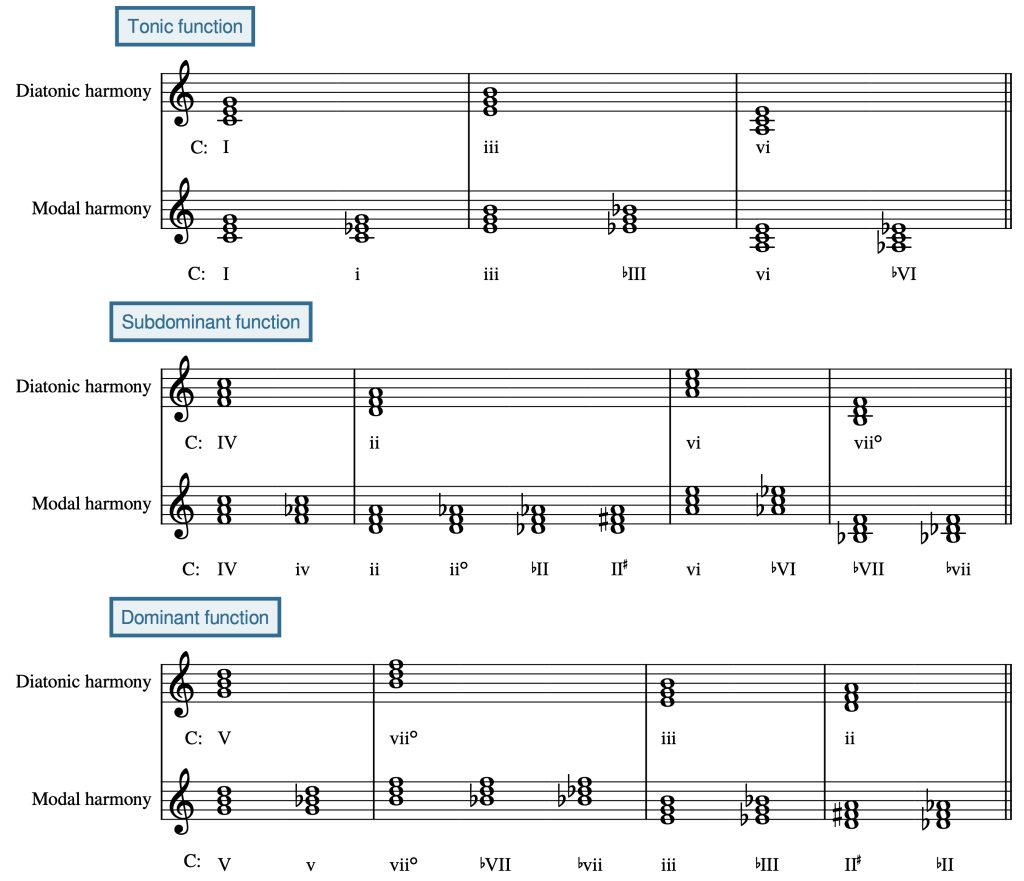

Mixolydian: ♭VII

Mixolydian’s color note is te (![]() ), as shown in Example 3. In major-mode pop songs, the ♭VII chord is borrowed from the mixolydian mode. ♭VII typically has dominant function, and you might think of it as a substitute for the traditional major-mode V chord in both the double plagal and mixolydian cadence schemas (Example 4).

), as shown in Example 3. In major-mode pop songs, the ♭VII chord is borrowed from the mixolydian mode. ♭VII typically has dominant function, and you might think of it as a substitute for the traditional major-mode V chord in both the double plagal and mixolydian cadence schemas (Example 4).

Example 3. ![]() (te) is the color note of the mixolydian mode. Important mixolydian harmonies have that color note in them: v and ♭VII. (iiio is not used.)

(te) is the color note of the mixolydian mode. Important mixolydian harmonies have that color note in them: v and ♭VII. (iiio is not used.)

Example 4. The double plagal schema and the mixolydian cadence schema are two especially common mixolydian chord progressions.

Double plagal

The double plagal schema, ♭VII–IV–I, which is discussed further in the blues-based schemas chapter, is also a mixolydian schema, due to the major tonic and the ![]() (te).

(te).

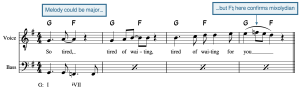

Subtonic shuttle

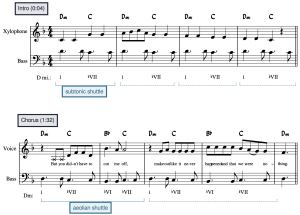

The most distinctive chord progression in mixolydian is the subtonic shuttle, ♭VII–I, or B♭–C in C major (Example 4 above). The subtonic shuttle is used continuously throughout the intro and first verse of “Tired of Waiting for You” by the Kinks (1965), where the instrumental parts shuttle between I and ♭VII throughout, while the melody emphasizes ![]() (te) as an embellishment and melodic goal (Example 5).

(te) as an embellishment and melodic goal (Example 5).

Aeolian: ♭VII and ♭VI

You may think of aeolian as equivalent to the natural minor scale. As a key or collection, though, aeolian and minor are different, because aeolian (as used in pop music) will prominently feature le and te ![]() . These color note scale degrees give us the ♭VI and ♭VII chords, which are the signature chords of the aeolian mode. (Note the use of flat signs in label of ♭VI and ♭VII, even though they are diatonic in minor/aeolian—this is to prevent confusion with viio.) Aeolian schemas use one or both of these harmonies (Example 6). The ♭VI chord has subdominant function, and the ♭VII chord has dominant function.

. These color note scale degrees give us the ♭VI and ♭VII chords, which are the signature chords of the aeolian mode. (Note the use of flat signs in label of ♭VI and ♭VII, even though they are diatonic in minor/aeolian—this is to prevent confusion with viio.) Aeolian schemas use one or both of these harmonies (Example 6). The ♭VI chord has subdominant function, and the ♭VII chord has dominant function.

Example 6. The subtonic shuttle, aeolian shuttle, aeolian cadence, and lament schemas are four common aeolian chord progressions.

Subtonic shuttle

The subtonic shuttle was introduced as a mixolydian progression, but the same progression can be used in aeolian. The difference is only in the quality of the tonic chord. If it’s major, then the subtonic shuttle implies mixolydian; if it’s minor, then the subtonic shuttle implies aeolian. In other words, ♭VII–i, or B♭–Cmi in C minor, is the minor version of the subtonic shuttle. This subtonic shuttle is used in the intro and verses of “Somebody That I Used to Know” by Gotye (2011, Example 7).

Aeolian shuttle

Another common shuttle in aeolian is i–♭VII–♭VI–♭VII. This progression can be understood as a shuttle between i and ♭VI, with a passing ♭VII chord along the way. This progression is featured clearly in the chorus of “Somebody That I Used to Know” by Gotye (2011, Example 7).

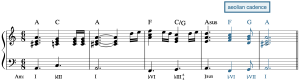

Aeolian cadence

In the aeolian shuttle schema, the consistent shuttling back and forth between I and ♭VI makes it difficult for a true cadence to be implied—a cadence means that a goal has been reached, but a circular progression like the aeolian shuttle doesn’t seem to have a goal. The aeolian cadence ♭VI–♭VII–i, or A♭–B♭–Cmi, is similar to the aeolian shuttle, but it’s goal-oriented: it cadences on the tonic chord, and it does not tend to be used as a loop. The aeolian cadence very frequently uses a picardy third, which means all the chords are major: ♭VI–♭VII–I, or A♭–B♭–C.

The aeolian cadence has a lot of cultural associations for many people and is typically associated with success and heroism. This cadence concludes the phrases of the Fellowship Theme from Lord of the Rings (Example 8, begins at 0:27). The aeolian cadence has also been called the Mario cadence, since the well-known fanfare at the end of each level of Super Mario Bros. uses this progression; the progression is often heard as a fanfare in other video games, such as Final Fantasy. In all of these examples, the cadence concludes with a picardy third.

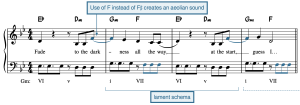

Lament

The lament schema has many variations, as discussed in the chapter addressing that schema. One particular flavor, i–♭VII–♭VI–v, strongly implies the aeolian mode due to the absence of a leading tone, which would imply a minor tonality, in favor of te ![]() , a color note of aeolian. This variation of the lament schema is heard in “I Don’t Like You” by Eva Simons (2012, Example 9).

, a color note of aeolian. This variation of the lament schema is heard in “I Don’t Like You” by Eva Simons (2012, Example 9).

Dorian: IV with a Minor Tonic

Dorian is a mode that sounds like minor, but with la instead of le ![]() , which produces altered harmonies including a major IV chord (compared to the minor iv in minor), shown in Example 10. Using a major IV chord in songs with a minor tonic is the primary marker of a dorian song, which would otherwise sound like it was minor/aeolian. The major IV chord in dorian usually has a subdominant function.

, which produces altered harmonies including a major IV chord (compared to the minor iv in minor), shown in Example 10. Using a major IV chord in songs with a minor tonic is the primary marker of a dorian song, which would otherwise sound like it was minor/aeolian. The major IV chord in dorian usually has a subdominant function.

Example 10. Dorian is distinguished from the natural minor scale by its ![]() (la), which alters the quality of the IV and ii chords. (vi° is not used.)

(la), which alters the quality of the IV and ii chords. (vi° is not used.)

The dorian mode is especially associated with funk, disco, and its derivative genres, where the dorian shuttle is especially pervasive. One example of many is “Dance, Dance, Dance” by CHIC (1979). Some people who haven’t listened to much music from these genres have trouble aurally recognizing the dorian shuttle and hear it instead as ii–V. Listening to a lot of funk and disco should help you learn to hear that “ii chord” as a i chord, even in more ambiguously dorian songs like Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” (2013, Example 11).

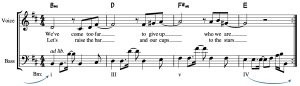

Dorian shuttle

The dorian shuttle alternates between a major IV chord and a minor i chord (Example 12). The overall effect of this progression is one of tonic prolongation. The upper notes of the IV harmony often form a neighboring motion that emphasizes la ![]() . A common variation on the dorian shuttle is expanded to i–IV–i7–IV. This further expands the neighboring effect in the upper voices.

. A common variation on the dorian shuttle is expanded to i–IV–i7–IV. This further expands the neighboring effect in the upper voices.

Example 12. The dorian shuttle uses minor i and major IV. It can be expanded to arch up to i7.

Lydian: II♯

Fi ![]() is the color note of the lydian mode, which results in a major II chord instead of the minor ii found in major (Example 13). This text refers to this chord as II♯ for clarity, with the sharp sign representing the raised third of the chord.

is the color note of the lydian mode, which results in a major II chord instead of the minor ii found in major (Example 13). This text refers to this chord as II♯ for clarity, with the sharp sign representing the raised third of the chord.

Example 13. Lydian is like major with ![]() (fi). This results in a major II chord. (iv° and vii are not used.)

(fi). This results in a major II chord. (iv° and vii are not used.)

If II♯ goes to V, as it typically does in classical music, the chord should be understood as as a secondary dominant V/V instead. But in pop tunes, II♯ often leads elsewhere, necessitating the II♯ label.

Very few pop songs are truly in the lydian mode all the way through the song, but many major-mode pop songs use a major II♯ chord in place of the typical minor ii, giving a brief lydian flavor while remaining overall in the major mode.

II♯ can have either subdominant or dominant function, and each is used in the following two schemas (Example 14).

Example 14. The II♯ chord is the characteristic chord of lydian and is used in both of these schemas.

Lydian shuttle

The most basic lydian chord progression is a simple shuttle between II♯ and I. Identifying this chord progression correctly can be tricky: because few pop songs are truly in lydian throughout, this II♯ chord is often neutralized later in the chord progression with a IV chord or a ii chord, which means the song is overall in major, but with a brief II♯ chord. This progression can be heard with some alterations in the opening of “Sara” by Fleetwood Mac (1979). “Sara” expands the lydian shuttle to include a Ima7 chord to harmonize an arching melody, and it also uses a tonic pedal underneath the II♯ chord. Later on in the song, the II♯ is neutralized by the use of a doo-wop schema. This is illustrated by Mark Spicer.

If the II♯ chord is never neutralized, it’s possible that the chord progression isn’t really I–II♯, but another shuttle that relates roots by step. For example, Taylor Swift’s “Starlight” (2012) has verses that alternate between A and B major chords (begins at 0:26), but they are IV–V in E major, not a lydian shuttle. This becomes clear in the chorus (0:56), which is harmonized with a rotation of the doo-wop schema. The subtonic shuttle discussed earlier in this chapter is another chord progression that relates two major chords by step. Remember that lydian is rare in pop music, and be careful when identifying this progression!

In this progression, II♯ functions as a dominant chord, leading back into the tonic with the half step between fi and sol ![]() .

.

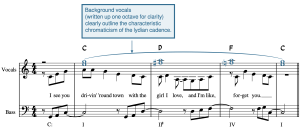

Lydian cadence

The most popular progression using II♯ is the lydian cadence II♯–IV–I, or D–F–C in C major. Notice that the lydian fi ![]() is immediately neutralized by the regular IV chord, replacing it with fa

is immediately neutralized by the regular IV chord, replacing it with fa ![]() . This schema also features smooth chromatic voice leading, which may partially explain the appeal of this progression. The clearest example of this schema may be Cee Lo Green’s “Forget You” (2010, Example 15).[2]

. This schema also features smooth chromatic voice leading, which may partially explain the appeal of this progression. The clearest example of this schema may be Cee Lo Green’s “Forget You” (2010, Example 15).[2]

Identifying Modes by Ear

If you are not used to playing in and listening to modes, it can be daunting to identify and distinguish modes by ear. Here is a step-by-step process for aurally distinguishing all the modes discussed here, illustrated as a flowchart in Example 16.

1. Identify the quality of tonic.

Listen for the tonic pitch. Then, listen for the whole tonic chord. Is the third of that chord major or minor? This distinguishes the major-ish modes (major, mixolydian, lydian) from the minor-ish modes (minor, aeolian, dorian).

2. Listen for  (ti or te).

(ti or te).

Compare the ![]() to the leading tone (ti) a half step below tonic that we typically hear in minor and major songs. If

to the leading tone (ti) a half step below tonic that we typically hear in minor and major songs. If ![]() is a whole step below tonic (te), then it’s lowered, which means that the song is (at least temporarily) in a mode.

is a whole step below tonic (te), then it’s lowered, which means that the song is (at least temporarily) in a mode.

If you heard a major tonic and ![]() is lowered (te), then you are in mixolydian.

is lowered (te), then you are in mixolydian.

If you heard a minor tonic and ![]() is raised (ti), then you are in minor.

is raised (ti), then you are in minor.

If your mode is not already identified, proceed to step 3.

3. Listen for other raised color notes—fi  in major, and la

in major, and la  in minor.

in minor.

If ![]() did not identify the mode for you, listen for other raised color notes.

did not identify the mode for you, listen for other raised color notes.

If ![]() is raised (fi) in a major-tonic mode, you are in lydian. If it is not, you are in major.

is raised (fi) in a major-tonic mode, you are in lydian. If it is not, you are in major.

If ![]() is raised (la) in a minor-tonic mode, you are in dorian. If not, you are in aeolian.

is raised (la) in a minor-tonic mode, you are in dorian. If not, you are in aeolian.

- Biamonte, Nicole. 2010. “Triadic Modal and Pentatonic Patterns in Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 32 (2): 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2010.32.2.95.

- Everett, Walter. 2009. The Foundations of Rock: From Blue Suede Shoes to Suite: Judy Blue Eyes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Persichetti, Vincent. 1961. Twentieth-Century Harmony. New York: W. W. Norton.

-

Powers, Harold S. et al. “Mode.” In Grove Music Online. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000043718.

- Spicer, Mark. 2017. “Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs.” Music Theory Online 23 (2). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23.2/mto.17.23.2.spicer.html.

- Tagg, Philip. 2011. Everyday Tonality: Towards a Tonal Theory of What Most People Hear. 1.3. New York: The Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press.

- Identifying Modal Schemas (.docx, .pdf). Asks students to aurally identify various modal schemas. Worksheet playlist

- Modal reharmonization composition project (.mscx, .musicxml, .pdf). Asks students to reharmonize Rihanna’s “Desperado” (2016) with modal schemas.

Media Attributions

- modal_harmonic_function

- mixolydian

- tired_of_waiting

- somebody_that_I_used_to_know 2

- LOTR

- I don’t like you

- dorian

- get_lucky

- lydian

- forget you

- mode_flow_chart-3

For modes in pop music, the color note is the pitch that distinguishes a mode from major (in the case of mixolydian/lydian) or from minor (in the case of dorian/phrygian).

A category of chords that sound stable, providing a sense of home or center. The I chord is the paradigmatic tonic-function chord, but vi and iii occasionally have tonic function.

Predominant function chords are those that transition away from tonic function toward dominant function.

A category of chords that provides a sense of urgency to resolve toward the tonic chord, including V and vii° (in minor: V and vii°).

Harmony that is based in a diatonic scale, such as the white notes of the piano. In analysis, diatonic harmonies may be labeled with with Roman numerals.

♭VII–IV–I, or B♭–F–C in C major. The term comes from duplicating the plagal relationship (IV–I) by applying it to IV as well (IV/IV–IV, or ♭VII–IV).

♭VII–I, or B♭–C in C major. This shuttle can imply mixolydian if the tonic chord is major, or aeolian if it is minor. In this shuttle, the ♭VII chord has dominant function.

A group of pitches being used as the basis for a composition. This term is more neutral than "key," which may imply a hierarchy.

i–♭VII–♭VI–♭VII. This progression can be understood as a shuttle between i and ♭VI, with the intermediate ♭VIIs acting as passing chords.

♭VI–♭VII–i, or A♭–B♭–Cmi in C minor. This schema implies the aeolian mode. Very frequently, the i chord is altered to be major, yielding a sequence of three major chords related by steps in the same direction. This progression, especially with a major I chord, is often associated with heroic themes in video games and movies.

Substituting a major I chord for a minor I chord (for example, using C major instead of C minor in a piece that is in C minor overall).

A harmonization of a descending upper tetrachord (1̂–7̂–6̂–5̂) in the bass.

IV–i, or F–Cmi in C minor. This shuttle implies the dorian mode. It can sound like ii–V to someone who is not used to the dorian mode.

A chromatic chord that temporarily tonicizes another key besides the tonic key, by taking on a dominant function in that new key.

I–II♯, or C–D in C major. This progression can easily be confused with IV–V in major or ♭VII–I in mixolydian, so one should be careful when referencing this progression. It implies the lydian mode.

𝄆I – VI – IV – V 𝄇, or C – Ami – F – G in C major.

Common alterations: substituting ii for IV; rotation.