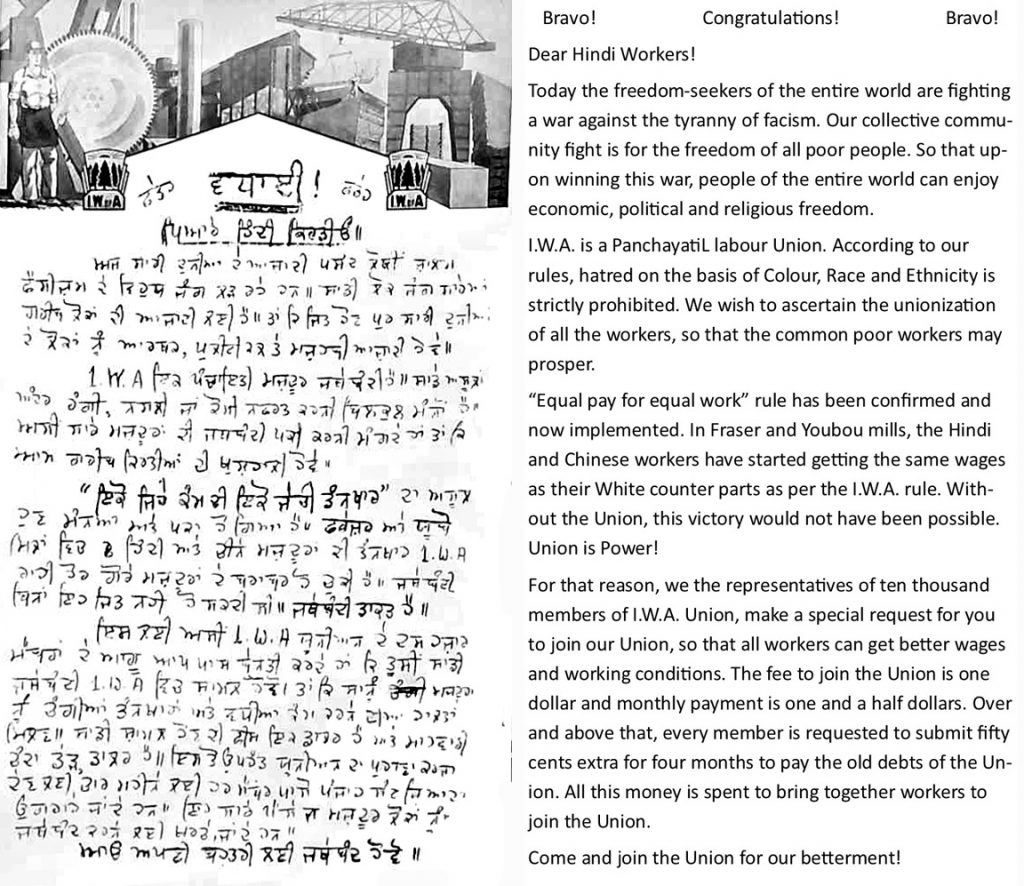

Labour’s long hostility towards Asian workers was slowly beginning to change in the 1930s, but the South Asian workers in the forest industry needed convincing that joining the union was in their interests.

Labour’s long hostility towards Asian workers was slowly beginning to change in the 1930s, but the South Asian workers in the forest industry needed convincing that joining the union was in their interests.

A significant development took place when the IWA leadership hired three organizers to break down the barriers of race and unite workers in the forest industry’s workforce. Roy Mah, Joe Miyazawa and Darshan Singh Sangha all played key roles during the union’s intense organizing drives of the 1940s.

The son of a poor Punjabi farmer, Darshan Singh Sangha — also known as Darshan Singh ‘Canadian’ — arrived in BC as a 19-year old student at the University of British Columbia in 1937. He joined the Communist Party in 1938 and was introduced through the party to the IWA.

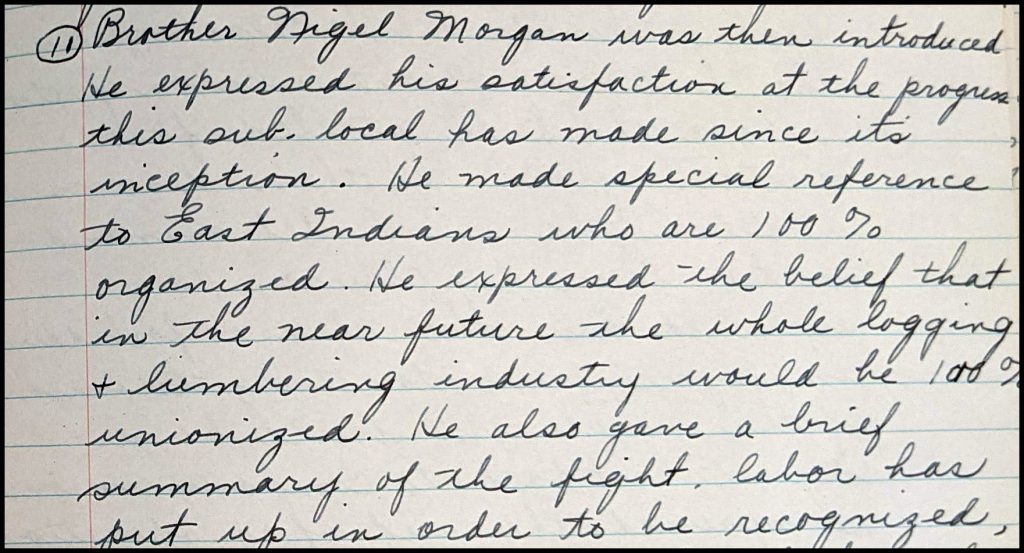

“Nigel Morgan met me and he made a proposition.” He said, “here is a vast industry, unorganized, Indians, Chinese, Japanese…and the white workers working in terrible conditions, being kept divided by the bosses. I agreed with him that I’ll be ready to work with them for the IWA. That is the time from which my baptism took place.” [1]

“So when I entered the industry, I found generally that most of the white workers were being paid 40 cents an hour. Most of the Indian and Chinese will get much less for the same work. And this was my experience where I found an Indian working for 25 cents an hour or 30 cents an hour, while other workers getting the full 40 cents. Invariably East Indians were the first to be fired and last to be hired. So furthermore, I found that only rarely was there an East Indian who would get any skilled job. They would mostly get jobs in the yard. Jobs loading the box cars and jobs on the green chain. The toughest jobs there. Now this had to do with the general situation as it prevailed in the British Columbia community. Racial discrimination was stark. In the first phase they were terribly afraid. Many many people would come over to me. They would say, ‘you are wasting your time’, that this way you will become a marked man. That the bosses will get me out of the industry, that I’ll ruin my chances of having any secure life.”[2]

“It was difficult for Darshan to talk to workers about the union. The biggest problem was that he had nowhere to hold the talks. The workers lived in bunkhouses, which were usually next to the mills, located on the mill owner’s property and it was simply not possible to talk openly there.”

“The meeting places for the Indian communities were the religious centres, the gurdwaras, and the talks couldn’t be held there because the mill owners had a lot of power in the community so the workers had to be contacted secretly. However, as Darshan’s influence spread among workers, he was eventually able to hold large meetings openly.” Sadhu Binning and Sukhwant Hundal, Darshan Singh Canadian: Ten Years in Canada, 1989. https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/km-6324/darshan-singh-canadian-ten-years-canada

Darshan Singh Sangha spoke extensively in an interview about what his early years with the IWA were like:

“In addition to that, some of the East Indian employers, they made some offers of soft jobs, good earnings and all that, if I would only give up the union work. So the first two years, I would say ’42 and ’43, it was tough going. A few people would join up. Most will stay out. Even those who were out, they were sympathetic, yet they were afraid.” [4]

“The white workers were also learning from their own experience. I suppose the spirit of many decades in which they had also terribly suffered, they recognized the need for overall unity in which they must enlist the support of these other ethnic groups.” [5]

“We, the East Indians, were deeply relieved when we saw that the IWA took a very solid and good stand on Indian independence and colonialism. They stood for independence of lndia and rights of Indian people to fight for it. This is very gratifying along with, that, on racial discrimination also, they took a consistent stand, that equality should be extended to all the sections and this racial discrimination is something which is anti-working class.” [6]

“There was not one man anywhere who crossed the picket line. And later on, after two or three days, picket lines were not just needed. Even though we did maintain them, they were not required to keep anybody out.”

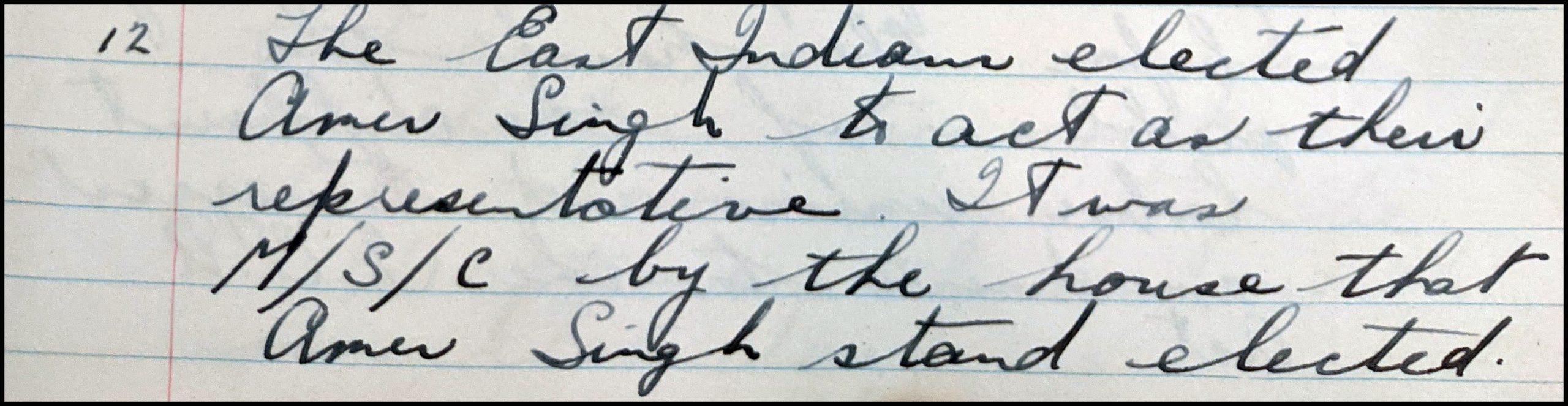

“Earlier I had said that in ’42 and ’43 they were hesitant. Sympathies were there but they would not dare to join. Then in ’44 and ’45 the upsurge gained more and once they were convinced that the organization was there to protect them and is strong enough, then they joined up in masses. Not a man would be left out.”

“In the East Indian community there is a tradition that whenever you have some common cause, then you must do everything to strengthen it. And you should not try to look for personal gain from any such community endeavor. Based upon it, during the strike days, there were many families who had difficult times. And I remember, in spite of everything through the forty day strike there was not even one East Indian who would come to the union for any sort of relief or any sort of aid. They would help each other or they would borrow.”

“Add to that, not one East Indian went to cross picket lines. For the first time, time and a half for overtime, fifteen days holiday with pay and then the seniority rights.” [8]

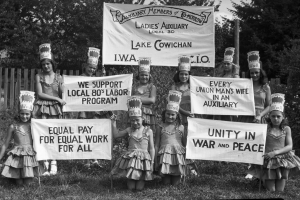

Swayed by Darshan’s Punjabi union pamphlets and fiery rhetoric, South Asian sawmill workers who had previously shied from white-run unions began flocking to the IWA. When the Youbou mill manager tried to evict Sangha for talking to the workforce, 90 South Asian employees gathered outside in the rain and told the boss that if he were thrown out, they would leave, too. Sangha was allowed to stay. At some predominantly South Asian mills, the vote to join the IWA was almost unanimous. [9]

Despite being an organizer for only a short time (1940-1948) Sangha left his mark on the IWA. Not only was he a successful grassroots organizer, he was elected as a District Trustee, attended and spoke at Conventions, and served on the powerful Convention Resolutions Committee. He became a strong voice for minorities within the union structure.

Harry Bains describes Darshan Singh’s impact on the union and its South Asian members:

In 1948, Sangha returned to India. In his resignation letter to the IWA he reminded union members: “One of the greatest achievements of the IWA was the uniting of all woodworkers – white, Indian, Chinese, Japanese – irrespective of race and color.” [10]

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979) in Daudharia (2004), 50. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett (1979), 53-54. ↵

- Harinder Mahil. Recording of reading Darshan Singh Sangha quotes. MP3 file, created 6 Dec. 2021, Union Zindabad! Project. BC Labour Heritage Centre. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979), 54. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979), 55. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979), 56. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979), 57. ↵

- Perry and Pritchett, (1979), 57-58. ↵

- Rod Mickleburgh, "Uniting Woodworkers Across Ethnic Divides". BC Labour Heritage Centre Blog, July 30, 2020. https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/ethnicdivides/ ↵

- Letter reprinted in Sadhu Binning and Sukhwant Hundal, Darshan Singh Canadian: Ten Years in Canada, , Simon Fraser University Library: 1989, 12. https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/km-6324/darshan-singh-canadian-ten-years-canada ↵