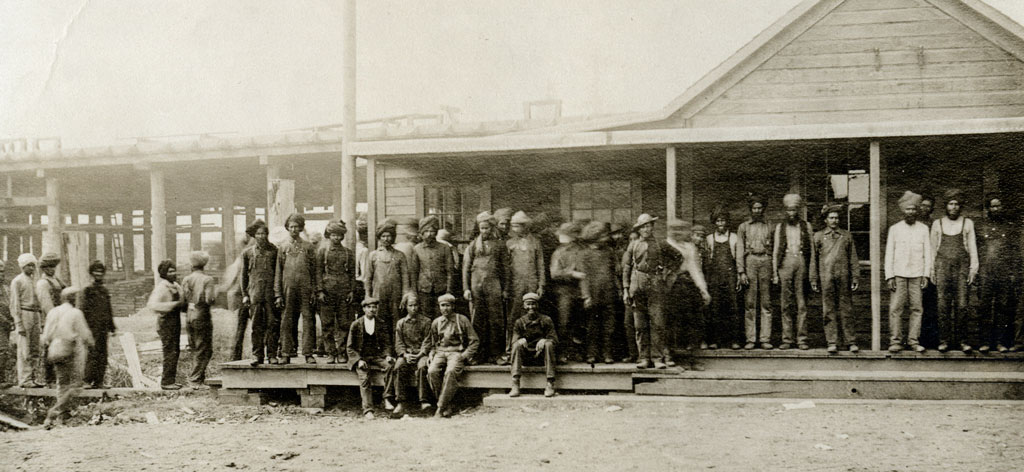

The earliest instance of South Asian workers formally participating in a BC labour dispute led by a union took place at Fraser Mills in 1931. After their fifth wage cut in 20 months, employees voted to strike September 17, 1931. Demands included less forced overtime, and better working conditions. These millworkers had recently joined the Lumber Workers Industrial Union.

There were sizeable numbers of Francophone, Japanese, Chinese and South Asian workers (incorrectly referred to as Hindus, even by the union) at Fraser Mills. The leader of the strike was 27-year-old shingle weaver Harold Pritchett, who went on to play a significant role in the further growth of lumber unions in Canada and the US.

The union’s demands included an end to the appalling segregated company housing provided for South Asian employees, and the use of labour contractors.

Workers from all ethnicities were represented on the Strike Committee, as well as all Relief Committees. [1] The few South Asian women who lived at Fraser Mills in 1931 also participated in the strike, presiding over the union’s community kitchen which served strikers at large outdoor tables using produce, chickens and eggs donated by Japanese and Chinese farmers.

“Everybody went out, although most of the Orientals who were very, very afraid of being shipped back to China or to Japan or to India. In spite of all, they stood up. Although they didn’t come very strong on the picket line, they never scabbed and they never bucked the union.”[2]

Interview with Boxie Singh Dosanjh, South Asian Studies Institute, 2019. Dosanjh was raised in Fraser Mills and recalls what conditions were like for his family. [3]

Skills were bartered among workers to provide basic services such as shoe repairs, hair cuts and supplying firewood. On day three of the strike, machine guns were mounted at the mill gates by police, who kept the strikers under constant surveillance.

At a mass strike support meeting in New Westminster, millworker K. Mariyana outlined their grievance with the long-standing exploitative practice of labour contractors. He said that Japanese workers had to go through a “Japanese boss”, just as there was a “Sikh boss” and “Chinese boss”, who for all intents and purposes, were agents for the company. Asian and South Asian workers were hired and fired at will. They had no protection. If they joined the union, they could be blacklisted, he told the large crowd – yet join the union they did.

The New Westminster Labour Council passed a motion that “the vermin-infested and unsanitary bunkhouses located in and on the property owned by Canadian Western Lumber Company and rented and occupied by Orientals and Hindus be abolished”. [4]

After 9 weeks on strike, the union ultimately accepted an offer by the company — which did not address all of the union’s demands. The Secretary of the Lumber Workers Union summed up these workers achievements in a letter to the Vancouver Sun:

“Instead of the Oriental scabbing on the white man, which has always been the bogey man that the lumber bosses have held over the head of the lumber workers, they have seen Japanese, Chinese and Hindus stand solid with Frenchmen, Swedes and practically every nationality under the sun.”[5]

After the strike, organizers such as Harold Pritchett were blacklisted from employment and struggled to find work through the rest of the Great Depression. Union recognition was a “line in the sand” which industrial employers would not concede until the 1940s, when the federal government finally passed legislation requiring employers to recognize and bargain with unions and unions were required to use grievance procedures instead of striking. Nevertheless, employer coercion persisted.

“I know the IWA was coming in to Fraser Mills (in the 1940s). My mother’s brother was working there as well and he was attracted to this. The organizers brought him in to show the Indians were also behind this movement. They suffered as a result of this because some recriminations occurred and he lost his job because of the union activity and in fact he couldn’t get a job after this and went back to India and married and came back. He never did get a job there. Most of our people kept out of the union. They wanted to join it, but they knew that the repercussions would be so severe because they could lose their job. My father talked about it but he kept his distance from it. My dad said “I have been assured that I can work there as long as I don’t take part in these activities” so he didn’t take part in these activities.” [6]

- Minutes of Strike Committee, October 10, 1931, quoted in Jeanne Williams Meyers, Ethnicity and Class Conflict at Mallairdville/Fraser Mills: The Strike of 1931, (Thesis, Simon Fraser University: 1982), 101. ↵

- William Elio Canuel, interview by Cheryl Pierson, sound recordings, 1972 March and May, Item AAAB0004, Reynoldston Research and Studies oral history collection, Royal BC Museum. ↵

- Boxie Singh Dosanjh, interview, 2019, South Asian Studies Institute, YouTube, https://youtu.be/L9lighEnFb8. ↵

- Rod Mickleburgh, host. "The 1931 Fraser Mills Strike", October 5, 2020, On the Line: Stories of BC Workers (podcast), BC Labour Heritage Centre. ↵

- M. Palmgren, "Workers' Demands", letter to editor, The Vancouver Sun, Nov 26, 1931, 6. ↵

- Ranjit Hall interview, 1984. ↵