Tara Singh Bains was a well-respected, religious man who came to BC from Punjab in the 1950s. Working at a mill in Nanaimo, Bains experienced anger from white workers who felt South Asians were working too hard, raising expectations of everyone. A white worker further up the chain was deliberately slowing down so that Bains had more work to do. When Bains asked him to stop doing it the worker said “I don’t speak your language”.[1]

After becoming active in the IWA, Bains was able to convince management to increase the number of workers per shift so the work could be more equally shared. Later, he took on executive positions in the union at a time when South Asians were just beginning to become active union members.

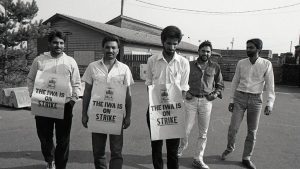

Barriers of language and cultural expectations could make union activism difficult. Once while on strike, Bains received a phone call from his brother-in-law, who had sponsored his travel and provided him a place to live upon arrival. The call was to tell him they had used their contacts with the labour contractor at a mill in False Creek to get Bains a job away from the strike. When he refused, saying he had taken a pledge to stand with the union his brother-in-law hung up the phone after saying “Well if you are so determined, we don’t want any relations with you.” Over time, they too would change their minds.

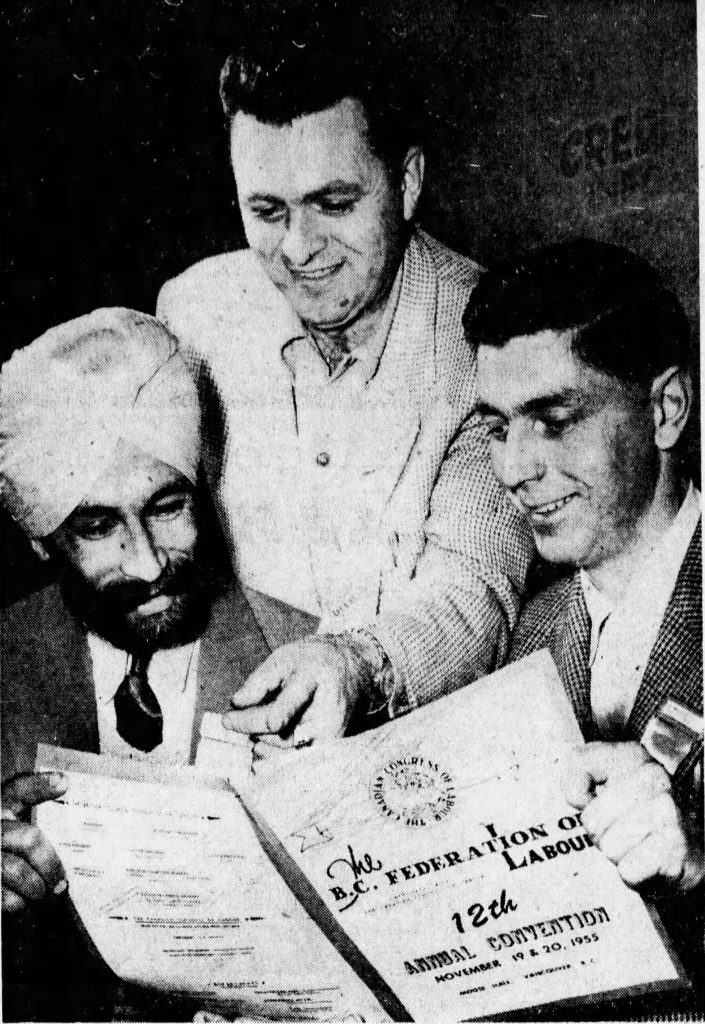

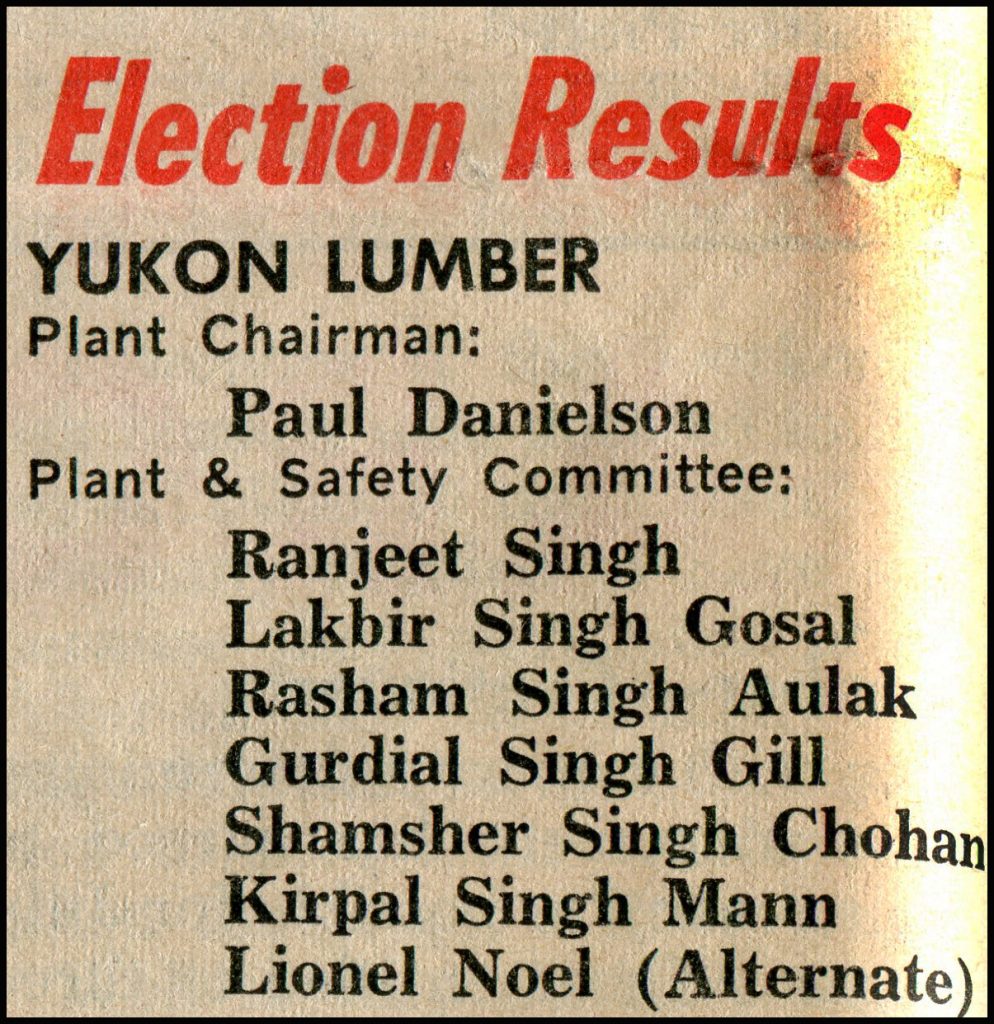

IWA Plant Committees were elected by the workers at each mill. They formed the backbone of the union because they dealt with day-to-day issues such as workplace safety and contract rights.

“Like the bees around the sweets”

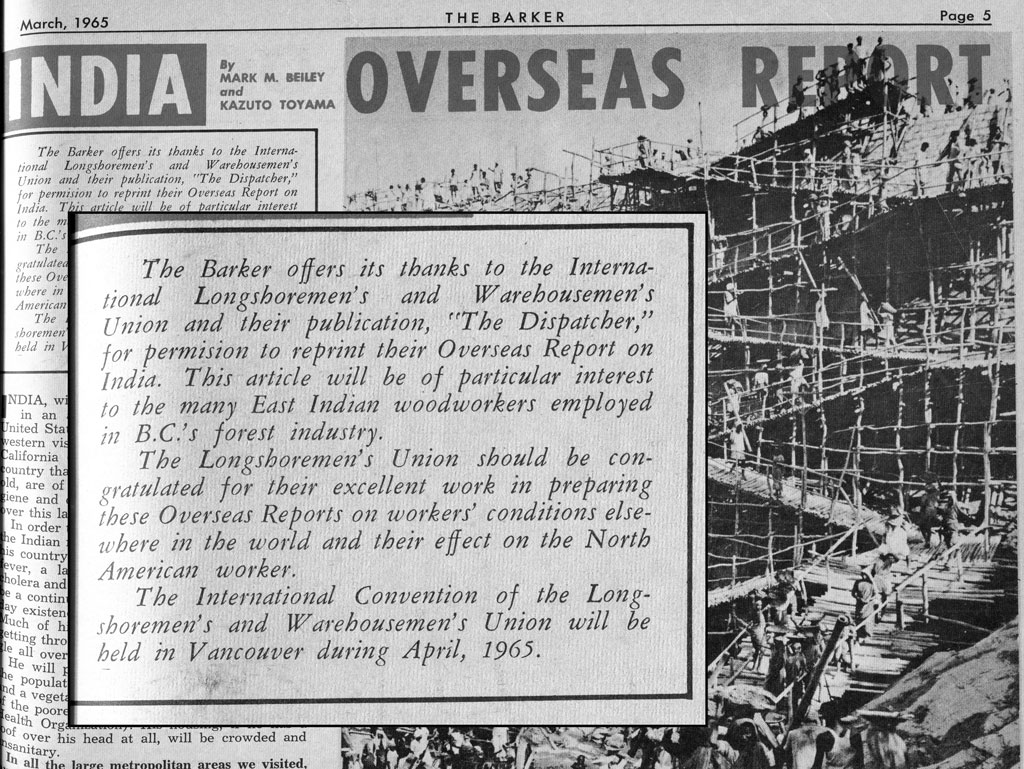

By the 1970s, South Asian Canadian workers had become active members throughout the IWA, participating in labour actions and taking on various leadership roles.

Convincing fellow workers of the value of the union became “very easy; the people was very aware, especially for the Punjabis, they get together like – you could have, thirty seconds, if something was happening against us, they’re like the bees around the sweets. Together. Same thing, our people, they are aware of what, you know, they are very aware of their rights.”[2]

Harry Bains recalled a racist incident which the IWA helped him to stand against. Inspired by the way it was handled, he became involved in the union and was quickly elected to the local executive. He described how South Asian sawmill workers saw the value of representing each other by taking on union positions and bringing those to the forefront. The union encouraged unity, respect and dignity between millworkers. The structure of the IWA was such that most issues were handled on the shop floor through “lunch room meetings”, so local shop stewards and plant committees were significant and powerful roles to hold.

In the sawmills, the union advocated for and achieved important contract language that met the specific needs of its South Asian members. Sucha Deepak explains that the IWA successfully negotiated improved leave provisions at the sawmill in Fort St James in northern BC. It allowed South Asian workers, based upon seniority, enough time to travel to India for marriages. This achievement was later expanded to the collective agreements in all operations around BC.